This report is the first installment of the #AutomationFever series supported by the Pulitzer Center.

“Automate your tasks with AI so you can reclaim your time for what truly matters.”

This is the typical pitch from artificial intelligence (AI) companies such as OpenAI, Google, Meta, and Amazon—one that governments and businesses around the world, including in Indonesia, have eagerly embraced.

But have workers actually become freer, more creative, and more in control of their time after adopting AI? Who decides which tasks are essential and which are disposable? Who sets the terms for when and where AI should be used? And what does this mean for how we find meaning in our work?

Rachma stared in frustration at her computer screen.

The AI auto-subtitling tool in her video-editing software struggled to translate compound words common in Indonesian: “rumah sakit” became “sick house” instead of “hospital”, and “kerja sama” turned into “work with” instead of “cooperation”.

She sighed. With translations this poor, she’d have to review a 45-page script line by line to make the subtitles accurate and readable—a frustrating waste of time.

Rachma was handling the subtitles for a historical documentary slated for submission to a prestigious competition in Asia. Beyond presenting a piece of Indonesian history to an international audience, the project was a chance to bolster the reputation of the media company she worked for.

Ideally, according to Rachma, subtitling involves at least three people: a translator renders the script into the target language, an editor embeds the translated subtitles into the video, and a producer reviews the final cut. Together they cross-check one another, keeping the subtitles accurate and easy to follow.

But the company had laid off its entire language-services department as part of efficiency measures.

That’s why the subtitling rested solely on Rachma. Her bosses, convinced that automation tools would lighten her workload, decided she no longer needed human assistance. All she had to do was “supervise” the machine.

And because supervising an AI tool was considered easy, it wasn’t seen as an additional burden for Rachma.

Rachma’s boss also tasked her with researching AI applications across other workflows, asking her to compare subscription fees, try out different tools, and map each one’s strengths and weaknesses.

All of this ate into the time she could have spent on her actual job. As a result, her main responsibilities kept piling up, unfinished.

“With AI, the workload just gets dumped on one person,” she said.

Rachma is one of many workers in Indonesia who have ended up doing more, not less, after their workplaces adopted AI tools.

Touted by the government to add US$366 billion to Indonesia’s GDP by 2030, AI has given many companies cover to pursue “efficiency” measures, including layoffs, in tough economic times.

Yet despite the hype, AI output still demands substantial human revision, ultimately increasing workers’ workloads.

“The narratives used to describe generative AI can elide its real capabilities, particularly in overstating claims about its abilities to replicate workers’ knowledge and expertise,” wrote researchers Aiha Nguyen and Alexandra Mateescu in a report titled Generative AI and Labor: Power, Hype, and Value at Work.

If applied recklessly, AI could worsen the already-precarious working conditions, especially amid a regulatory vacuum that allows companies to avoid accountability for any unintended consequences.

Beyond wage devaluation, workers risk losing the meaning and satisfaction they once found in their jobs. Reliance on automation tools can also undermine workers’ ability to develop the skills they actually seek.

“The claims that technology companies made about AI capabilities, that it can streamline teams among other things, are starkly different from the reality we are seeing today,” said Sheila Njoto, a sociologist who studies the impact of AI in the workplace.

To date, there is no conclusive evidence that AI has boosted productivity at a national level.

If anything, according to Sheila, the most apparent impact is that workers are being pulled deeper into an ever-faster, never-ending current of capitalism.

“Rather than gaining more free time for life outside of work, those who managed to accomplish things faster thanks to AI are being punished with even more work,” said Sheila.

Rachma’s case also shows how some tasks at the workplace, such as translation, are increasingly treated as trivial and therefore left to machines.

Yet as part of the production team for a historical documentary at one of Indonesia’s largest television networks, Rachma and her colleagues did more than put a show on air. They must ensure that the program was intellectually rigorous and legally compliant.

Often, the nuanced, relational dimensions of social interaction are most critical in this line of work when navigating high-stakes decisions.

“Occupations are not merely collections of discrete, operationalizable tasks; they encompass ethical norms and standards, context-based knowledge, and institutional memory, as well as constantly shifting social networks and relationships,” said researchers Nguyen and Mateescu in their report.

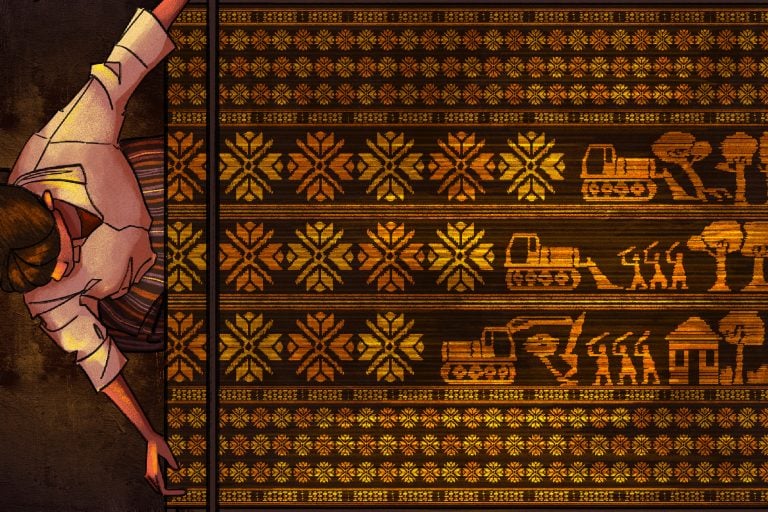

The widening set of tasks now labeled nonessential, coupled with the assumption that supervising a machine is “easy”, points to a decline in the value of work itself. This is what experts refer to as the “devaluation” of human labor, where human contribution is discounted once it is paired with machines.

Devaluation and precarity long predate AI. They began during the Industrial Revolution, for instance, when textile and garment artisans were absorbed into factories and became wage laborers. In recent years, we have also witnessed the devaluation of drivers as they turned into gig workers on ride-hailing apps.

In the era of AI, devaluation and precarity are set to spread across more occupations and industries at an even faster rate. The impact will vary by industry structure and context. In most cases, workers will have little say over whether AI is integrated into their workflows, and even less over how it is applied.

“It’s efficiency for capital owners, but more work for the workers,” said Guruh Riyanto, a coordinator at SINDIKASI, a union of media and creative industry workers.

Indonesian media coverage tends to frame technological advances (and now AI) as something inevitable, beyond intervention, and therefore to be accepted in whatever form they take.

Rarely do we see reflections on what workers sacrifice in the name of “adaptation”. Workers’ aspirations have always been excluded from the design of both the technology and the public policies (or lack thereof) meant to regulate them.

When technology is treated as non-negotiable and closed off from redesign, the conversation turns deterministic. It’s a dead end. Once again, the most vulnerable are asked to bear the consequences of so-called “progress”.

In contrast, today’s AI models stem from a series of deliberate choices made by a handful of technology companies. Political forces that privilege power and large-scale investment have shaped AI as we know it.

These interests engineered the hype, encouraging haphazard adoption of AI across many aspects of our lives, including in the workplace.

Manufacturing the AI Hype

AI development dates to the 1950s and spans a wide range of techniques and applications.

In 2011, Google began building and testing deep-learning systems and, in 2012, applied them to Android’s speech recognition. That move helped kick off the tech industry’s fixation on data and deep learning, as many firms found this subset of AI relatively easy to commercialize.

Since then, deep learning has powered Google Translate, search engines, targeted ads, social-media algorithms, e-commerce platforms, ride-hailing apps, and countless other digital products we use today.

The risks of deep learning have been widely discussed by experts.

Because deep learning is extremely data-hungry, it has driven many technology companies to compete to mine data, by ethical means or otherwise. It is also prone to producing biased outputs. That bias is especially hard to fix because it can seep into every layer of the deep-learning pipeline.

Despite these risks, deep learning continues to dominate AI development. Researchers who warned technology companies about its dangers were fired or sidelined, while funding for alternative AI research was absorbed by major players.

AI became widely known in 2022, when OpenAI released ChatGPT, the largest and most ambitious manifestation of deep learning. Because ChatGPT could generate new content beyond just analyzing data, it became known as generative AI. This capability stunned the public.

Within two months after its initial launch, ChatGPT managed to attract more than 100 million users. It was the fastest app growth on record.

Seven years before ChatGPT’s release, OpenAI was founded in 2015 by a group of technologists and investors, including Elon Musk, a tech billionaire, and Sam Altman, then head of the startup accelerator Y Combinator.

From the start, the founders positioned OpenAI to lead in the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI), a hypothetical stage where AI could match or surpass human thinking on almost any task. AGI’s proponents believe it would be capable of resolving humanity’s most complex global problems, including the climate crisis.

Karen Hao, a journalist at MIT Technology Review, challenged the notion: wouldn’t the computational power required to build such advanced AI generate significant carbon emissions?

OpenAI’s response was essentially that once AGI existed, it could fix everything, including the climate impacts from its own creation.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), however, has repeatedly stated that the challenge in tackling the climate crisis lies not in the lack of funding or technology, but a lack of political will.

Many AI experts have argued that more gradual, small-scale AI approaches tailored to community needs are no less sophisticated and may, in fact, be more beneficial to society. In this view, there is no urgent need to pursue ever-larger AI systems.

Even so, OpenAI has shown little concern for these warnings, continuing to chase the pipe dream of AGI. That vision encouraged the company to build ever-larger models that demanded vastly more computational power.

Because that ambition required enormous funding, OpenAI ramped up its publicity. One tactic was to portray its then-current model, GPT-2, as dangerously powerful. This created the impression of a major breakthrough, which caught Microsoft’s attention.

In July 2019, OpenAI secured US$1 billion from Microsoft despite having no clear pathway to getting return of investment.

OpenAI then began mining data on an even bigger scale to develop GPT-3, by pirating books and content from across the internet.

In the media, OpenAI has repeatedly pitched a fantasy. CEO Altman said AI would deliver universal basic income, AGI would become a superintelligence, and every business, organization, industry, and discipline would advance.

The message reads as if AI and AGI would be immensely powerful—beneficial yet dangerous—and only OpenAI could contain the monster while profiting from it on humanity’s behalf.

Sensational publicity, designed to evoke equal parts fear and awe, was central to persuading people that OpenAI’s models were groundbreaking and sophisticated.

This eventually yielded several outcomes.

First, investment poured in. To this day, OpenAI has raised US$64 billion in funding. Second, OpenAI now sets the direction of AI development globally, forcing competitors to build similar models. Third, OpenAI became an influential voice in shaping AI public policies worldwide.

Finally, and most importantly, OpenAI was able to sell its AI models as paid services, generating revenue.

This is how the hype around generative AI was manufactured and amplified, wave after wave. The dream of solving humanity’s problems through automation became a collective aspiration. For others, the hype sparked fear of being left behind if they didn’t adopt AI soon enough.

The fever then spread. Google, Meta, and Amazon poured vast sums into building energy- and water-hungry infrastructure to power their own massive generative-AI models, then embedded those models across their software products.

The hype also pushed many non-tech companies to scramble for AI tools. Motivated by the fear of falling behind and buoyed by inflated optimism about technology, managers rushed to cram AI into every workflow they could find amid an economic downturn.

They were convinced that AI would solve their problems, grow the business, shield them from obsolescence, and cure the industry’s ills.

‘Do It or Lose Your Job’

Today, workers across industries have little choice but to adopt AI tools, under pressure from production targets and managerial insistence.

“As workers, we’re placed in an impossible situation: if you don’t do this, you lose your job. If you don’t follow, you lose to your competitors,” said Nabiyla Risfa Izzati, a labor law lecturer at Gadjah Mada University (UGM).

As competition intensifies, the hidden costs of AI adoption fall on workers.

Skolastika, who goes by Tika, a freelance creative worker based in Tangerang, Banten, explained that staying competitive means paying for premium AI features and investing in higher-spec hardware (like a more powerful laptop) to run them smoothly.

“The industry is getting tougher. For creative workers, AI isn’t free. We have to be smart about choosing the cheapest options,” said Tika.

“[AI] is simply unavoidable, because industry demands are shifting so much faster now.”

Tika relies on Descript, Canva, and Adobe for her day-to-day work. Her freelance projects span video and social-media production, storytelling, and translation. On one project, she also oversaw and designed the content-production workflow.

Based on Tika’s observations, AI has already displaced many junior-level positions. In graphic design, for instance, clients now frequently hire only an art director—a senior position directing the work—without the junior designer who would typically carry out the execution.

“Stuff a bunch of references into the AI tool and boom: out comes a ‘creative product’,” said Tika.

The instant process of production flooded the market with content. Oversupply, combined with limited audience attention, eroded the economic value of each piece.

Budgets for creative production have shrunk. This creates a vicious cycle: jobs are cut, the remaining workers are forced to adopt automation tools, and their workload only grows heavier.

As a result, creative work is increasingly treated as just another drop in an ocean of content. The sense of meaning is steadily eroded.

“We live in a world where art, design, and video no longer need to carry creative value, to be life-changing, or to keep you up at night in awe,” Tika said.

“I don’t get to make hero projects anymore.”

It isn’t only creative workers like Tika who are losing a sense of meaning in their jobs. Many others, especially in care fields such as mental health and education, have reported the same issue. Offloading parts of their work to automation tools has stripped away much of the fulfillment they once found.

Work itself, which ideally is a source of purpose in helping communities thrive, is being reduced to fragmented operational tasks. The more abstract dimensions of craft and care are pushed aside.

Some tasks are meant to be performed slowly and with intention, either because they are essential, or simply because workers enjoy doing them. But from the vantage point of profit, they hold no value, said UGM lecturer Nabiyla.

“In that equation, the human perspective becomes irrelevant. All that matters is efficiency. Workers’ needs are reduced to monetary, while spiritual needs are secondary,” she said.

Ultimately, this shows that AI serves productivity rather than workers.

“It’s the output that gets helped,” said Nabiyla.

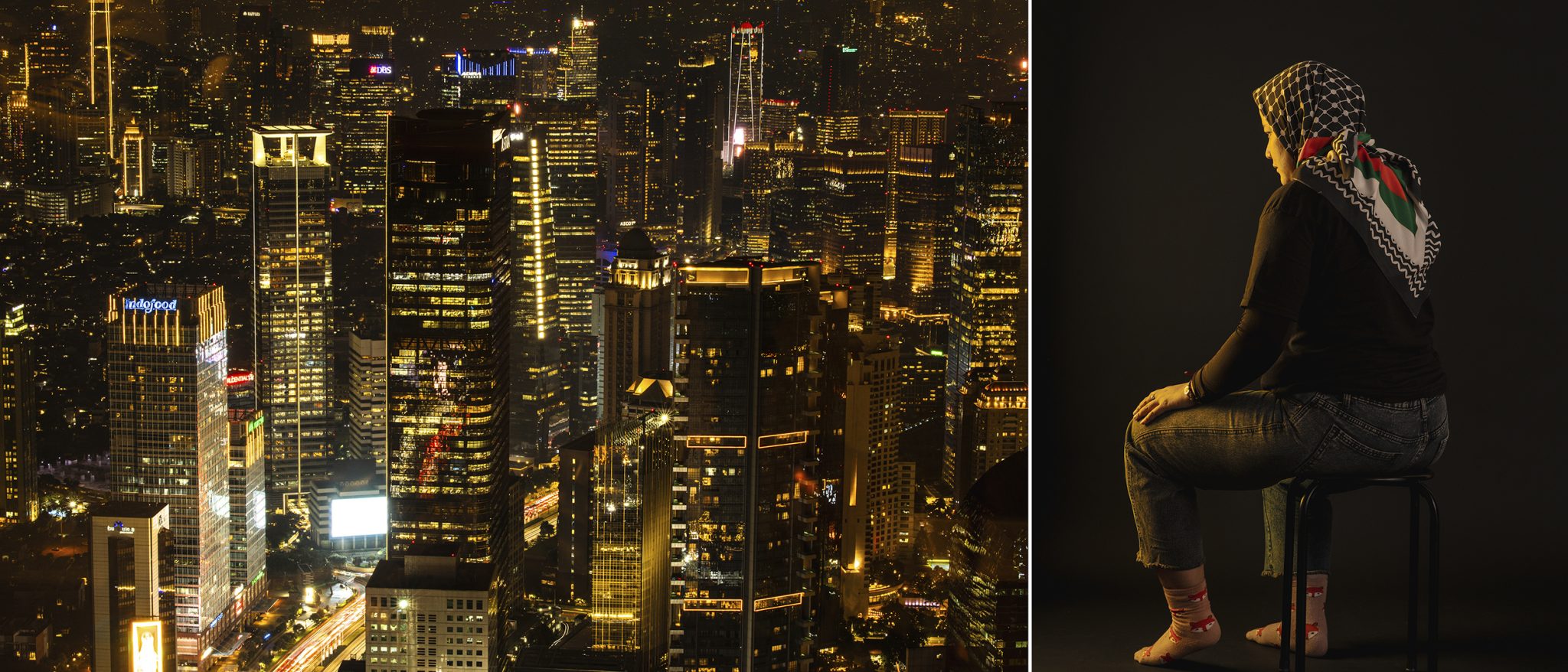

Rika (not her real name) often works up to 13 hours a day as a mental-health professional. Beyond seeing clients and preparing reports, analyses, and workshop materials, she has also been tasked with producing social-media content to promote her clinic.

In the digital era, this dual burden is common. Professionals in many fields are expected to double as content creators.

Rika turns to chatbots like Brave Leo AI and Gemini to generate summaries of mental-health materials with visuals. She then imports the draft into Canva, makes minor layout adjustments to fit her company’s style guide, and within 45 minutes, the content is ready to post.

In the past, she would do close reading and original research before selecting topics she felt were relevant to the public. She enjoyed that process, as it aligned with her passion and the expertise she built over a decade. But the demands of her dual role have left her little time to rest.

Pressure to produce, sudden requests, and a push from her boss have driven her to rely on AI.

“My boss scolded me for not taking advantage of the technology. So I caved in,” said Rika, who asked that her real name not be used for fear her employer might accuse her of tarnishing the company’s reputation.

With AI, Rika has been able to impose some order by streamlining her workflow. She can prepare multiple promotional posts in advance and schedule them.

Even so, she feels that churning out content for volume and “online activity”, with little regard for quality, has stripped her work of meaning. What used to be the product of close reading, careful research, and deliberate topic selection has become routine posting that brings no sense of accomplishment.

Rika is still exhausted every day. Her working hours haven’t changed, still 13 hours a day, and she earns only slightly above her city’s minimum wage while also setting aside part of her income to support her retired parents.

The same loss of fulfillment after handing over certain tasks to automation tools is felt by Dana (also a pseudonym) who works as a teacher at an international school in West Jakarta.

His school demanded that teachers design learning methods to cultivate critical thinking and curiosity among his students. And yet, almost every year the teaching concept would be scrapped to make way for a new curriculum, new methods, and new directions. Sometimes it’s the new administration’s policy, sometimes just a marketing tactic to attract admission.

Having taught since 2015, Dana once found deep satisfaction in designing and applying his own teaching strategies, and seeing them make a difference for his students. But that kind of work takes time and careful thought. It shouldn’t be reinvented every year because, in Dana’s words, education is not a “testing ground”.

The constant changes in teaching methods with no adequate training, combined with a heavy load of administrative tasks, left Dana struggling to meet the overwhelming demands.

So he turned to ChatGPT for help with lesson plans. It provided strategies for teaching grammar and math, instructions for quizzes, and even exam questions. Dana felt he had lost a part of the work he truly cherished.

“Every teacher has their own unique strategy in the classroom. When I started using prompts, I felt like I’ve lost the soul of teaching. It’s gone,” said Dana.

Ironically, in class, Dana urged his students not to take shortcuts by AI for their homework. He noticed that while his students were able to read, they struggled to draw insights from the text. To counter this, he taught them how to locate sources on their own and worked to build their critical-reading skills.

Dana felt guilty. He saw himself as being dishonest, since he was the one relying on ChatGPT to lighten his own workload.

“We try to design lessons that would cultivate a sense of curiosity, but the curiosity itself feels artificial,” he added.

Like Tika, the experiences of Rika and Dana highlight how workers are losing the space to exercise their own agency—the freedom to define their own goals, passions, and sense of meaning through work.

“That’s what’s being taken away,” said AI sociologist Sheila Njoto. “It is as if you live only to work, and work [only] to survive, not to help people or communities flourish.”

Even on technical terms, AI still falls short. It can certainly assemble lesson plans from thousands of data points across the internet. But according to Fahriza Tanjung, the secretary-general of the Federation of Indonesian Teachers Unions (FSGI), only teachers truly understand the specific circumstances and needs of their students.

“I don’t think AI can ever match what teachers create themselves,” Fahriza said.

Handing too many tasks over to automation tools can also stunt the very skills that workers want to hone.

A freelance journalist, who asked to remain anonymous, told us that they use ChatGPT, Google Translate, and automatic transcription software to draft, write, and polish articles.

Working alone in a fast-paced environment without the support of a traditional newsroom, the journalist has come to rely on these tools. But as a result, they feel their own skills have stagnated.

“The final product is indeed better [with AI], but I feel like my growth has stalled for the past five years in writing and translation. I would blank out a lot,” they said.

“With these convenient tools, it’s all copy-paste. The output might look fine, but I ask myself: what am I really learning from this?”

These workers’ experiences show that adopting AI does not necessarily free up time, boost creativity, or sharpen skills. On the contrary, it often piles on more work, strips meaning and fulfillment from the job, and blunts creativity.

To make matters worse, workers often have no say over when, where, and how AI will be used, else they risk retaliation for speaking up. That’s why most sources in this report chose to remain anonymous or use a pseudonym.

Several workers report that they receive verbal pressure to adopt AI immediately. Some were mocked for questioning whether certain tasks should be handed over to AI. One media worker said that two of their colleagues were fired after criticizing how AI was implemented at their office.

Almost all the workers we interviewed said there’s no room to express their views about automation candidly at work. For many, the interview for this story was the first time they had voiced their concerns.

All these pressures come amid low wages, weak protections, rising taxes and living costs, and shrinking job opportunities as competition intensifies.

Workers’ rights are formally regulated under Indonesia’s Labor Law. Unfortunately, the law has no provisions for informal workers, who make up 58% of the labor force. Moreover, it offers no protection for new or emerging forms of employment.

According to Nabiyla, the solution lies in expanding protection for all types of work and labor relations.

“[The Labor Law] should be made as broad as possible so that whatever form or dynamic work may take in the future, it still falls under its scope,” Nabiyla said.

But strengthening workers’ protection will likely face resistance from a government that often favors the tech industry. Hype fanned by tech companies, a culture that glorifies production at all costs, and the entrenched belief that “too much” regulation stifles innovation all combine to obstruct harm-mitigation efforts.

“The government is aligned with these tech bros who have convinced them that [AI] will benefit Indonesia,” said Sheila.

“It’s a paradigm issue. I am afraid that individuals alone can’t bring about real change.”

By now, the damage is done. Data has been extracted. Data centers—physical infrastructures built to support AI computation—have devoured precious land, water, and energy. Work structures have shifted, and workers are already trapped in a more exploitative system.

According to Sheila, the best option for workers is to join unions or collectives. This could be an effective avenue, at the very least, to help negotiate workers’ interest within companies.

“I can’t help but feel helpless seeing how the elites in power respond [to AI]. But I remain hopeful because more and more people are becoming aware,” she said.

“What matters now, more than ever, is perseverance.”

This piece was originally published in Indonesian. The English-language editor was Viriya Singgih.