Warning: This reportage features descriptions of violence. The names of several sources have been changed to preserve their safety.

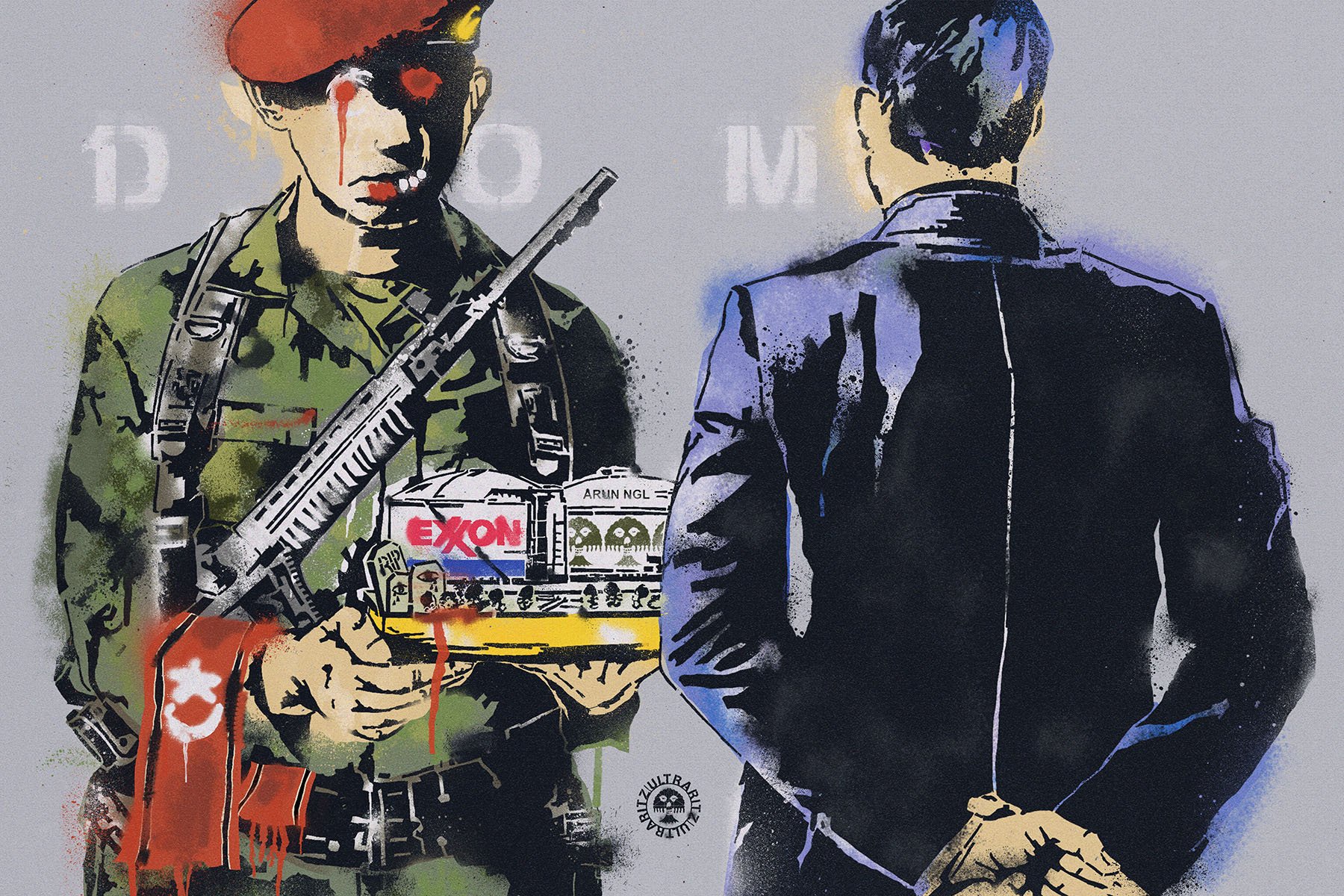

In August 2022, the US District Court for the District of Columbia released the testimony of 11 victims of alleged human rights violations connected to the operations of the US oil and gas giant ExxonMobil in Aceh.

Release of the testimony opened a new chapter in a decades-long process of uncovering the truth of what happened to the victims. For this report, the Multatuli Project and SinarPidie.co visited Aceh to see the sites suspected of bearing silent witnesses to violence. We spoke to the witnesses and former detainees who spoke at hearings convened by the Aceh Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Aceh TRC or KKRA), which is expected to soon release its final report.

I

Testimony of a ‘Labi-Labi’ Driver

AROUND 1990, after evening prayers, Nuh, a driver, regularly took his public transport van, known locally as labi-labi, to the Rancong Tactical and Strategic Unit (Sattis) Post at the Exxon complex in Lhokseumawe, North Aceh.

On those nights, Nuh (not his real name) was tasked with picking up soldiers from Rancong, formally known as Sattis Satgas B/North Aceh.

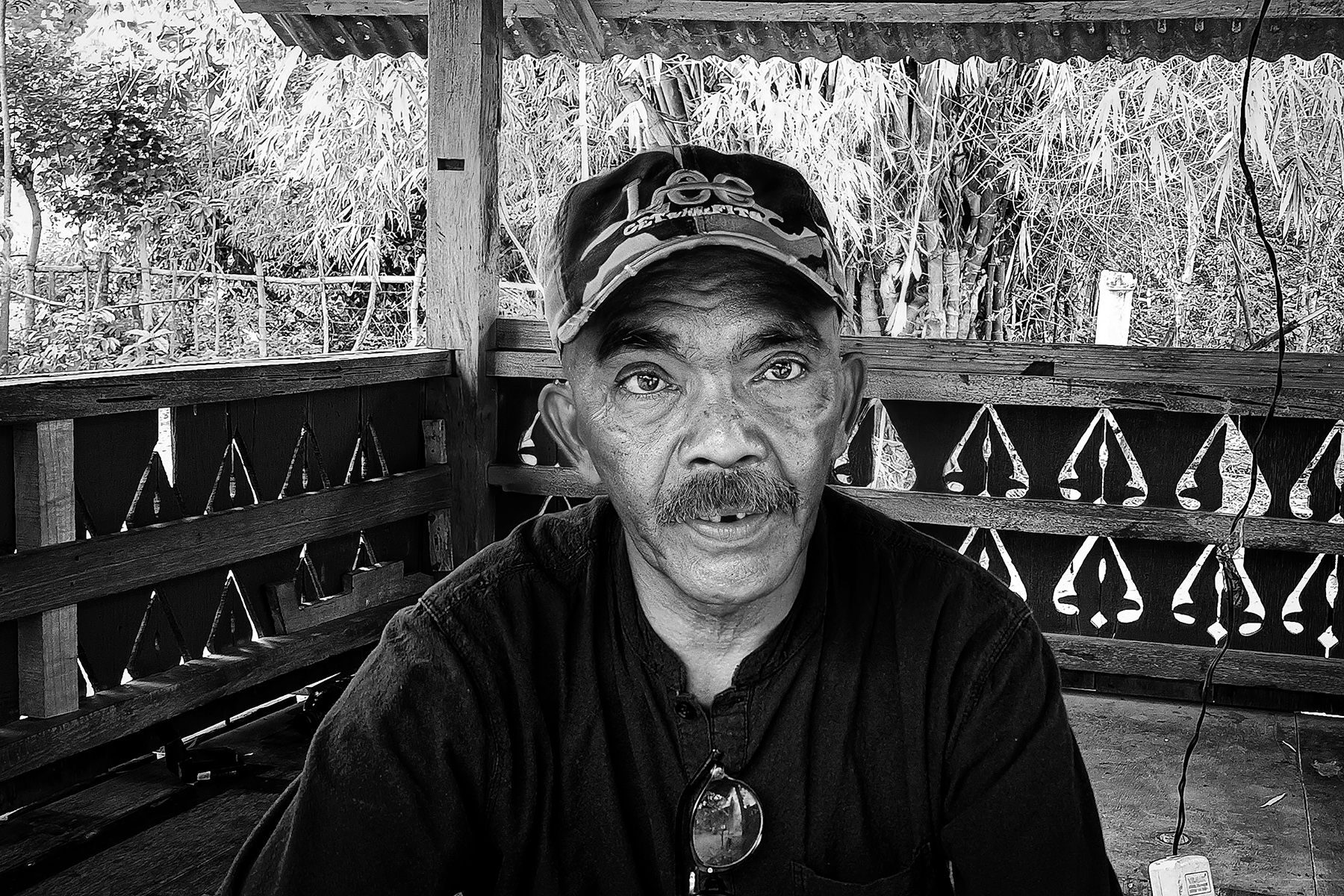

“At 8 p.m. I had to be at the Rancong Post. I would bring the soldiers to Lhokseumawe City, where they would look for entertainment. At midnight, I would bring them back,” said the 54-year-old man, during an interview in August 2022.

The distance was about 16 kilometers, about a 30-minute drive.

“I never had a day off during those days,” said Nuh. “If I refused the soldiers’ requests, the labi-labi I drove daily to make a living might have disappeared.”

From morning to night, Nuh delivered passengers to the city.

Sattis Rancong Post was part of the PT Arun Natural Gas Liquefaction Facility. Established in 1974, PT Arun was the world’s largest producer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the 1990s. Its refinery at the port of Blang Lancang, about 10 kilometers from Lhokseumawe City, covered around 271 hectares.

Arun was a joint venture between Mobil Oil Indonesia, a subsidiary of Mobil Oil Corporation, and PT Pertamina, the Indonesian state-owned oil-and-gas company, on one side, and the Japan-Indonesia LNG Company (JILCO) consortium on the other.

On November 30, 1999, Exxon Corporation purchased Mobil Oil, forming a new entity called ExxonMobil, and inherited 30% of PT Arun’s shares.

While Arun is typically cited as a success story in exploiting Indonesia’s natural resources, it is also associated with grim accounts from residents of Aceh, who allege that they were tortured by Indonesian Military (TNI) troops sent to secure the company’s operations at Sattis Rancong Post.

A year after PT Arun started operating in Lhokseumawe in 1977, the firm built schools ranging from the kindergarten to the senior-high level inside the facility complex. “Teachers at Arun’s schools were also brought there from outside Aceh, such as from Java and Padang,” said Nuh.

Arun built about 30 residences for the teachers. The homes, each about 16 square meters and equipped with one bedroom and one bathroom, were divided among three hamlets. All of the homes faced the sea.

Nuh recalled that the Indonesian Army used several of the residences to detain and torture prisoners accused of involvement in the “GPK”, or security disruption movement. GPK is how the Indonesian government referred to the Free Aceh Movement in the 1990s. Known locally as GAM (its Indonesian acronym), the Free Aceh Movement waged a decades-long insurgency against Jakarta.

In the mid-1990s, five teachers and their families lived in the official residences at Sattis Rancong Post. The other homes were used as offices by Kopassus, the Indonesian Army’s special forces group.

The Indonesian government closed the surrounding area to the public as part of its Operasi Jaring Merah (Operation Red Net) counter-insurgency program, which ran from 1989 to 1998, and during a state of Military Emergency and Civil Emergency (DOM) it declared from 2003 to 2005.

* * *

At Sattis Rancong Post, Nuh once met the renown religious leader Teungku Bantaqiah and his wife, Nurliyah.

“Teungku Bantaqiah’s wife was a cook at Rancong Post when Teungku Bantaqiah was detained,” said Nuh.

On October 24, 1993, soldiers arrested Bantaqiah for possession of 1.5 tons of cannabis that they alleged were to be sold to GAM.

Bantaqiah was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment by the Lhokseumawe District Court and incarcerated at Tanjung Gusta Prison in North Sumatra. As a political prisoner, Bantaqiah was given amnesty by then-president B.J. Habibie and released in 1998.

Bantaqiah also led the Babul Al Nurillah Islamic boarding school. He was accused of storing weapons for GAM at the school.

On July 23, 1999, Bantaqiah and 56 others–including some of his students and his son–were shot dead in Beutong Ateuh, Nagan Raya, by soldiers of the Indonesian Army under the direction of the Lilawangsa Military Resort Command (Korem 011) and Battalion 328 of the Army Strategic Reserves Command. The accusations against Bantaqiah were never proven.

According to Nuh, detainees who were killed or died over the years were buried in the yard of the Sattis Rancong Post by soldiers who used PT Arun’s facilities.

“One evening, 10, 12, or 20 prisoners who had been executed were transported in a Chevrolet pickup. When there were hundreds of executed prisoners, they were transported by Mitsubishi Colt trucks,” said Nuh.

The bodies were then transported and buried at Seuntang Hill and Tengkorak Hill at Sattis Rancong Post. (Tengkorak means skull in Indonesian).

“I once saw several prisoners in the pickup or Colt truck–some who were even still alive,” recalled Nuh.

Seuntang Hill, in Lhoksukon, North Aceh, is 57 kilometers from Settis Rancong Post and was within ExxonMobil’s exploitation area, the South Lhoksukon Field.

This is where a mass grave was discovered on August 22, 1998, by a team from the National Human Rights Commission led by Baharuddin Lopa. Twelve human skeletons were found in one hole.

South Lhoksukon Field was among dozens of gas wells in Block B owned by ExxonMobil: North Sumatra Bee (NSB). There were two clusters, the South Lhoksukon Field A and South Lhoksukon Field D.

PT Arun produced LNG with gas supplies from Arun Field and South Lhoksukon A and D.

Tengkorak Hill is about eight kilometers from Lhoksukon. The area, a waste disposal site for PT Arun, was previously known as Seureukee Hill, and was located in a village with the same name. It’s also where Army soldiers once instructed villagers to smooth over mass graves.

Nuh said detainees at the Sattis Rancong Post were typically tortured at one or two in the morning.

“Near the water tank, outside the Rancong camp yard, there is also a mass grave.”

Apart from Rancong, soldiers were deployed to Arun sites spread along 90 kilometers of pipeline, all the way to ExxonMobil’s gas wells in North Aceh.

Posts like Rancong were vital for project security. Posts A-13, A-1, and Point-A were sites of brutal action levelled against civilians by the military.

In its report on Aceh, “Peace with Justice? Uncovering Past Violence” (2006), the Commission for Missing Persons and Victims of Violence (KontraS) said that ExxonMobil paid up to Rp 5 billion a month to the military and police to support its operations.

ExxonMobil gave the security forces logistical support, like food and fuel–as well as bulldozers that were used to dig mass graves, the report said.

“Funds included a daily allowance of Rp 40,000 per soldier, transportation facilities, a post office, a barracks, a mess hall, radio, telephones, and more. In addition, there were at least 17 Army/National Police posts funded by ExxonMobil, with a total of 1,000 personnel from various units,” according to the KontraS report.

II

The Story of “Alpha”, Who Escaped a Torture Post

On Saturday, December 14, 1991, “Alpha” was arrested by Kopassus personnel at Taskforce A/Pidie. The unit’s headquarters was in an Army dormitory complex in Bakti City. He was accused of working as a link in an ammunition supply chain for a GAM group led by Jamal Burak.

Jamal was one of around 400 young people recruited by Hasan Tiro, the founder of GAM. Hasan, who had close ties with Libyan president Muammar Gaddafi, sent many young Achenese to the North African country between 1986 and 1989 to train as prospective commandos.

Jamal was in the second batch that went to Libya, wrote M. Isa Sulaiman in Aceh Merdeka: Ideologi, Kepemimpinan, dan Gerakan (Free Aceh: Ideology, Leadership and Movement, 2000).

“Alpha” was also a civil servant for the district government.

One day in early December 1991, soldiers, acting on an informer’s information, conducted a raid to foil an ammunition shipment in Krueng Seumideun village. “Alpha”, who was in the village with Jamal Burak, fled the ensuing gunfire.

He was arrested at home a week later and held at the Sattis A/Pidie Post in Lameulo for 10 days.

Every morning at 3 a.m., “Alpha” and other detainees were immersed in a 25-square-meter pool and told to fight each other while soldiers urinated in the water.

Hours later, the torture resumed. Soaking wet, “Alpha” was told to count the number of bed bugs on the wall of the interrogation room.

“From Lameulo, I was detained at Lhokseumawe Prison. Because the International Red Cross (ICRC) was scheduled to visit, I was transferred to a cell in the Military Police’s Lhokseumawe office. At Lhokseumawe Prison, I was held for five nights. While in that 2-by-2-square-meter cell, I was detained for six nights,” said “Alpha”, during an interview in August 2022.

“Alpha” said he was transferred so ICRC representatives would not see his battered condition.

Later, “Alpha” was incarcerated in a one-room house with a bathroom near the Sattis Rancong Post.

“The (place of confinement) was a teacher’s house,” he said.

Capt. Sugiarta was then the commanding officer at Sattis Rancong Post.

Sugiarta’s full name is Ngakan Gede Sugiarta Garjitha. He served 20 years in Kopassus after graduating from the Indonesian Military Academy in 1981 and eventually retired with the rank of major general.

“Alpha” said he was not tortured at Rancong, only interrogated.

“The questions asked were ‘Who attended the handing over of ammunition at Krueng Seumideun?’ and ‘Who supplied the ammunition?’”

At Rancong, “Alpha” was assigned work in a public kitchen, and thus was able to leave detention. He could not go beyond the post gate, except when on duty as an imam at the Al Hidayah Mosque (Arun Mosque).

“At 8 p.m, after the isha (evening) prayer, usually the new prisoners would arrive, and I wasn’t allowed to hang around outside.”

* * *

“Alpha” was detained at Sattis Rancong Post for about six months. In June 1992, he was taken to the Lilawangsa Military Command in Lhokseumawe.

“The plan was to take me to Gandhi Medan Prison on Saturday, but this didn’t happen. It was postponed to Monday,” said “Alpha”. “In the early 1990s, I heard that the torture in Gandhi Medan Prison was worse than Rancong.”

One Saturday, when “Alpha” led the maghrib (dusk) prayers at the Al Hidayah Mosque, it was raining heavily. Lightning strikes hit a resident and a coconut tree. “Soldiers at the picket post went into the barracks because they were scared,” said “Alpha”.

He used the opportunity to escape and walked three kilometers to Simpang Rancong. The checkpoints between Sattis Rancong Post and Simpang Rancong were empty.

Taking public transport to Bireuen, “Alpha” continued to the provincial capital, Banda Aceh, and then to Teupin Raya, Pidie, where he joined a GAM guerrilla unit in the forest.

“After a year in the jungle, I crossed over to Malaysia.”

“Alpha” had returned by the time Aceh voted on an autonomy referendum in November 1999. However, when local conditions deteriorated, “Alpha” crossed over again to Malaysia.

He eventually returned and settled in Pidie in 2006, one year after GAM and the Indonesian government signed the Helsinki agreement in Finland on August 15, 2005, to end the insurgency.

To this day, “Alpha” suffers from damaged hearing due to the torture he experienced at Sattis Lameulo Post. His leg was also injured.

III

Basri Usman and Capt. Bambang Kristiono

Basri Usman was selling rice at a stall in Pondok Baru, Bener Meriah, on January 20, 1992, when he was arrested by soldiers from a Kopassus unit on duty at Sattis Lameulo Post.

At that time, Basri had been in Pondok Baru for only three months. A resident of Puuk village, Basri is Jamal Burak’s younger brother.

“Four soldiers arrested me in Pondok Baru. One of them was Pak Bambang,” said Basri, during an interview.

Basri was referring to Bambang Kristiono, then a captain and commander of the Sattis-A/Pidie Post in Kota Bakti in 1994.

In July 1997, Bambang, by then a major, formed Team Mawar, which was behind the kidnapping of 22 pro-democracy activists.

Jakarta’s High Military Court II-08 sentenced Bambang to 22 months in prison and discharged him from the Army. He is currently a member of Indonesia’s House of Representatives (DPR), representing the Gerindra Party.

After arriving at Sattis Lameulo Post, Basri was tortured. He was beaten with an electric cable and a 55-cm long wooden block.

Later, Basri was held captive in the home of Adi Karya in Rambayan. There, he met GAM detainees who were trained in Libya.

“It was there that Kopassus confronted me with former Libya-based GAM members who’d been arrested,” said Basri.

He was held captive for a week. “I was electrocuted and my head was trampled on.”

In the 1990s, Adi Karya was a contractor for Pidie regency’s public works office. His homes in Rambayan and in Blang Asan were used by Kopassus as Sattis posts.

Basri was also taken to the Sattis B/North Aceh Sattis Post in Rancong for two days. “In Rancong, in one house, there were four of us,” he said.

“I was put in a drum that was secured with a padlock. The drum was then rolled on the ground. When it stopped rolling, the soldiers beat the drum over and over. My ears hurt. I could barely breathe inside.”

From Rancong, Basri was taken to the Lilawangsa Military Resort Command and then to Alue Buket, Lhoksukon in North Aceh for three months.

“In Alue Buket, Kopassus used the former office of public irrigation works for interrogations and detention,” said Basri. “The questions the soldiers asked were about the activities and whereabouts of my brother, Jamal Burak.”

On February 13, 1992, Jamal Burak was shot dead in a gun battle in Beuah, Delima district, Pidie. Basri was then moved from Alue Buket to the Sattis Lameulo Post, where he was held until his release in 1994.

“I was still subject to mandatory reporting until 1997,” he said.

Sattis posts were built in at least four sectors in each sub-district, according to the executive summary of Komnas HAM’s report “Serious Human Rights Violations in Aceh (Rumoh Geudong and Other Sattis Posts)”.

Field operations under Military Resort Command 011/Lilawangsa were carried out by Kopassus troops. Sattis posts served as detention sites for those questioned, as well as for detainees who were interrogated, tortured or executed.

Otto Syamsuddin Ishak, a sociologist and a Komnas HAM commissioner from 2012 to 2017, said the Sattis Rancong Post was the command center for the government’s Operasi Jaring Merah.

“Operation Jaring Merah was a counter-guerrilla operation to ward off insurgents using shock therapy,” Otto said in an interview.

GAM guerrillas were very close to the “local community”, according to Otto. “So, this operation was like separating fish (GAM) from the water (the community). To get the fish, or for the fish to emerge, the water was stirred.”

Kopassus soldiers assigned to Operasi Jaring Merah in Aceh were from Group 2/Sandhi Yudha, Otto said.

The acts of torture experienced at the Sattis posts were alike: shocks were delivered by a hand-cranked device without a voltage meter.

“The dignity of all the victims held captive at each Sattis post was shattered,” he said.

In a copy of a routine Kopassus report received by Project Multatuli, soldiers from District Military Command I/Bukit Barisan were said to have carried out activities supporting Operasi Jaring Merah in the Korem 001/Lilawangsa area.

The report said the operation had four objectives: to search for and destroy GAM figures and members; seize enemy weapons; dismantle GAM’s clandestine networks in villages and cities; and dismantle the cannabis syndicate network, considered a major source of the movement’s funds.

Kopassus personnel carried out a two-phase intelligence operation to support Operation Jaring Merah, under Kodam I/Bukit Barisan.

First, Kopassus agents targeted GAM members and operational assistants to compromise GAM activities, ambush and search houses, collect clandestine data, and recruit and train their own agents within GAM.

Second, GAM members were targeted in the forest, through combat operations such as raids, patrols and interceptions, as well as clandestine data collection for the development of larger operations.

The people of Aceh referred to the Kopassus assets or informants as cuak.

Hasan Tiro declared the Free Aceh Movement on December 4, 1976. Its aim was to fight for the nation of Aceh Sumatra, as a continuation of the Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam.

Political centralization and unequal policies over control of natural resources under the New Order regime were the factors behind GAM’s emergence.

“It was probably not by chance, for example, that Aceh Merdeka’s declaration of rebellion in late 1976 and its first military action in 1977 coincided with the opening of PT Arun, Aceh’s first major facility for the extraction and processing of LNG,” wrote Geoffrey Robinson in Rawan Is as Rawan Does: The Origins of Disorder in New Order Aceh (1998).

IV

From Rumoh Geudong to Rancong

More than 300 detainees are thought to be buried at the Sattis Rancong Post complex.

According to Nuh, the figure includes prisoners executed between 1991 and 1998.

“The number of detainees at Rancong Camp soared when Rumoh Geudong in Pidie was vacated. All the detainees at Rumoh Geudong were transferred to Rancong Camp,” said Nuh.

“The prisoners were suspended from the ceiling. Their feet didn’t touch the floor. In the morning, prisoners who had not been crushed by torture were ordered to run on gravel. Their feet were beaten with a 23-centimeter-long wooden block.”

Rumoh Geudong was vacated some time after Suharto stepped down from the presidency in May 1998. Human rights victims under the DOM period spoke up. Members of Aceh’s civil society and students demanded the DOM be repealed.

The DPR then formed a fact-finding (TPF) team on July 22, 1998, led by retired TNI member Hari Sabarno, who was then House deputy speaker. The team comprised Ghazali Abbas Adan from the United Development Party (PPP), Lukman R. Boer from the Development Works (Karya Pembangunan) party, and Sedaryanto from the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI) factions in the House.

During their fact-finding visit to Rumoh Geudong, Pidie, in July 1998, its prisoners were allegedly temporarily transferred to various places, including Sattis Rancong Post.

Farida Haryani, Director of the Foundation for Acehnese Social Economic Development (PASKA), remembers the team’s visit.

“In Pidie, the TPF first held a meeting with victims at the local legislative council building. Initially, the number of victims allowed to enter was limited to just five, as a sample,” said Farida.

Farida helped around 500 widows of DOM victims in Pidie meet with the TPF. Dozens of trucks lined the road in front of the Pidie council building. Farida was then the secretary of Forum Peduli HAM, a forum for human rights led by Ghazali, from the fact-finding team.

Victims and their supporters came to Farida after they were banned from the Pidie council building.

“I protested to Bang Ghazali. He then removed the tape attached to the door and the victims […] barged in,” said Farida.

The fact-finding team divided into two groups. Hari Sabarno’s group visited Rumoh Geudong, and Ghazali’s group visited Pinto Sa, the Sattis post in the former Baro Raya Irrigation building in Tiro.

At Rumoh Geudong, Hari Sabarno was greeted by the post commander, Bilie Aron (Rumoh Geudong), as well as First Lt. Sutarman and his soldiers. Hari was shown around outside.

Farida urged Hari to enter the building. “Inside the house, Pak Hari Sabarno found instruments of torture, such as stun devices, hammers, wires and ropes,” said Farida.

Farida got the impression that Hari knew about the torture in the house.

“At the beginning of the meeting with the Sattis Post commander in the Rumoh Geudong courtyard, Pak Hari asked him whether it was a place of torture. The post commander replied that they had just arrived, that there had just been a change of troops,” said Farida.

Farida then guided Hari to a list of personnel and scheduled transfers posted on the wall. “Feeling he had been lied to, Pak Hari delivered a blow to the commander,” said Farida.

The fact-finding team was in Aceh for a week. Members also met with widows in Cot Keng village, Bandar Dua district.

On August 7, 1998, then-president BJ Habibie issued an order to repeal the DOM.

* * *

A few weeks later, on August 20, 1998, a Komnas HAM team led by Baharuddin Lopa arrived in Banda Aceh.

The team found two human skeletons in a mass grave at Kuala Tari Beach in Pidie.

Unlike the DPR team, which only heard victim testimony, Komnas HAM brought a forensic doctor from the North Sumatra Regional Police, Dr. Ritonga, and two medical assistants to investigate allegations of gross human rights violations.

The team prepared to exhume a mass grave in Rumoh Geudong.

“Pak Baharuddin Lopa asked for a meeting with the victims to be held at Rumoh Geudong,” said Farida. At that time, Kopassus had vacated the site.

The team did not find intact skeletons in the mass grave. “What was found at that time were finger and leg bones, and hair,” said Farida.

Farida received information that Kopassus exhumed some human remains from the Rumah Geudong mass grave just four days before the Komnas HAM arrived.

After the team met with the victims and investigated the grave at Rumoh Geudong, the house was burned down.

In Deah Teumanah village, Trienggadeng district, Komnas HAM uncovered another mass grave, with five skulls.

The team departed for Jakarta on August 23, 1998, after exhuming yet another mass grave in Bukit Seuntang, North Aceh.

V

Bahagia Escapes Death

In May 1998, in Ujong Rimba village, East Mutiara district, Pidie, Bahagia Yusuf was arrested at his home and grocery store. He was accused of knowing the whereabouts of 25 weapons.

Bahagia was detained for eight days at the Rumoh Geudong Sattis Post and then taken to the Rancong Sattis Post.

“The leaked information about weapons occurred after Yusuf Cubo, a former GAM member, was arrested in Malaysia and then returned to Indonesia. Yusuf was detained and tortured at the Sattis post in Rancong. Unable to bear the torture, he leaked information about 25 weapons,” said Bahagia, now 67, said in an interview.

Yusuf Cubo joined the interrogation, said Bahagia.

Antje Misbach, in Politik Jarak Jauh Diaspora Aceh ( “Long Distance Politics of Aceh’s Diaspora”, 2012), wrote that 545 Acehnese detained in five prisons in Malaysia (Semenyih, Macap, Umbo, Linggeng, and Juru) were deported to Aceh on March 26, 1998.

“The majority of those who were deported from Semenyih were detained for two weeks at the Rancong detention camp,” wrote Antje.

After arriving at Sattis Rancong Post at 1 a.m., Bahagia was soaked for three hours in a two-square-meter pool and then tied to a door frame. He was detained with two others. They were all chained together, by the neck, while in their underwear.

“In Rancong, I was tied and suspended. I was electrocuted from 1 p.m. until morning. I was hit with an electric cable and a stingray tail. I was detained in Rancong for two months,” he said.

A few days before the withdrawal of auxiliary Army personnel from Aceh, Bahagia was transferred from Rancong Sattis Post to a post at PT Perkebunan Nusantara Paya Bujok, a plantation company in Langsa, North Sumatra. At that time, Lilawangsa was under the command of Col. Dasiri Musnar.

“The soldiers questioned me and several other detainees about the whereabouts of our relatives in East Aceh, so we could be returned to them. I said I had relatives in Sungai Raya,” said Bahagia.

On August 16, 1998, Bahagia and another prisoner he didn’t know were put into the back seat of a Daihatsu Taft car.

It turned out that Bahagia was not taken to Sungai Raya. He was dumped in the middle of the road on Jalan Banda-Aceh Medan, in Beunot village, Syamtalira Bayu district, North Aceh.

“From inside the car, we were kicked out to be run over by another car traveling from behind at high speed. I survived because I fell into a ditch,” he said. He did not remember what happened to the others; records showed they were later found dead near the car.

“By then I no longer had my wits about me. I was treated in Malaysia,” he said.

VI

Post Operations of PT Arun and ExxonMobil

The Indonesian Navy occupied Sattis Rancong Post after Kopassus withdrew from Aceh at the end of August 1998.

Today, the four hectares on which the Sattis Rancong Post once stood are the site of a Navy base. The teachers’ residences were torn down; the land was blocked off with wire fencing.

Rancong village actually ceased to exist in 1974, as all its land had been acquired by PT Arun, which also bought all the land in Blang Lancang village.

In the 1970s and 1980s, residents of Rancong and Blang Lancang villages refused offers to be relocated to North Aceh, due to its remoteness.

After the signing of the peace agreement between GAM and the Indonesian government on August 15, 2005, around 200 cottages were built for traders on about 20 hectares of land previously owned by PT Arun.

The area also has a new name, Pantai Pulau Seumadu, or Seumadu Island Beach, and is adjacent to the East Batuphat village. PT Arun’s land assets near the beach were also handed over to the Navy for use as a base in 2017.

Outside the commercial area, residents have built wooden houses as well as semi-permanent homes.

From Jalan Medan-Banda Aceh, the former Sattis Rancong Post can be reached from Simpang Empat Rancong in Hamlet A, East Batuphat village. Simpang Empat Rancong faces the PT Arun housing complex.

Stretching between Simpang Empat Rancong to the Sattis Rancong Post is about 2 kilometers of asphalt road. About 1 kilometer of the road to the former post remains open.

In October 2014, PT Arun shipped its last LNG cargo to the Korea Gas Corporation.

In 1973, Pertamina signed an LNG sales contract with Japanese companies such as the Industrial Bank of Japan, Kyushu Electric, Kansai Electric and Far East Oil Trading.

“The contract with the Japanese companies was the largest LNG sales contract at that time, with annual sales of 7.5 million tonnes, or the equivalent of 180,000 barrels of crude oil per day. This contract was binding for 20 years,” wrote Teuku Khaidir and Arif Widodo in Mengembalikan Kemasyuran Arun (“Returning the Glory of Arun”, 2021).

From 1978 to 2014, PT Arun shipped 4,269 cargo loads of LNG to Japan and South Korea, with individual shipments worth up to US$10 million.

In 2015, after Arun’s LNG shipment to Korea, all assets, such as refineries, ports, power generators, pumps, jetties and employee housing, were taken over by PT Perta Arun Gas, a subsidiary of PT Pertamina, which operates the LNG receiving and regasification terminal at the site.

“Now, all land owned by PT Arun that was not used by Perta Arun Gas belongs to LMAN,” or the State Asset Management Institute, said Abdul Gani, the village head of East Batuphat, in August 2022.

LMAN is an organizational unit within the Finance Ministry.

Exxon began withdrawing from Aceh in 2009, when it handed over the Pase Operational Area, a natural gas producer in operation since 1981, to Triangle Energy (Global) Limited.

The Pase Operational Area, which spans more than 900 square kilometers, currently has three productive gas wells (A1, A5 and A6).

While ExxonMobil Indonesia’s Cooperation Contract in Block B and North Sumatra Offshore was due to end in 2018, the company relinquished all its assets to PT Pertamina Hulu Energi in 2015.

Block B was managed by PT Pertamina Hulu Energi until November 2020, when it came under an Aceh government-owned enterprise, PT Pembangunan Aceh (PT PEMA), through its subsidiary PT Pema Global Energi. Meanwhile, the North Sumatra Offshore Operational Area is operated by PT Pertamina Hulu Energi.

Eight years before ExxonMobil handed over the Pase Operational Area, the International Labor Rights Fund, a human-rights organization based in Washington D.C., filed a lawsuit in US court against ExxonMobil, alleging the company’s involvement in human rights violations in Aceh.

The International Labor Rights Fund filed suit in the US court on behalf of 11 Acehnese residents.

ExxonMobil has filed nine motions to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claims. The legal process has been stalled in the courts for more than 20 years.

Translator: Julia Winterflood

The names of victims and perpetrators were also included in Amnesty International’s 1993 report titled Indonesia: “Shock Therapy”, Restoring Order in Aceh 1989-1993 and in a report from the Independent Commission for Investigating Acts of Violence in Aceh (KIPKA), which was formed by Presidential Decree No. 88 /1999.

This coverage was written in collaboration with Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR).