From May 2021 to December 2022, we published 224 pieces in Indonesian, 148 of them news articles, 27 photo stories, 47 opinion pieces or personal essays and two commentaries published under the right of reply. The data on these publications demonstrates our efforts to challenge certain dominant practices in Indonesian media, which is typically Jakarta-centric, male-centric and catered to elites rather than the marginalized.

Of our 224 published pieces, 27.2 percent were national news, 29.5 percent covered topics on Java (excluding Jakarta) and 28.6 percent covered areas outside Java. Jakarta-oriented stories accounted for 14.7 percent of our published work.

We encourage our contributors, regardless of their gender, to interview both men and women as primary sources. Consequently, 45.1 percent of our publications have women as primary sources, including transwomen, and 1.3 percent have non-binary sources. Our figure for women as primary sources for general news is four times Indonesia’s industry average of 11 percent, according to 2018 data from the Tempo Data and Analysis Center.

Further, we have encouraged more women and nonbinary people to write for publication. Of our 224 pieces, 39.7 percent were written by women (including transwomen) and 3.6 percent by non-binary people.

To serve the marginalized, we amplify voices and topics rarely covered by the media: labor, gender justice, class relations, indigenous peoples, land conflicts, environmental degradation, state violence, voices of the poor, queer voices, farmers and fishermen, as well as youth voices on labor issues, environmental damage, and land conflicts.

In February 2023, a message came to our membership account on WhatsApp. It was from Yuli, a journalist based in Baubau, a small town on Buton Island, Southeast Sulawesi. Yuli informed us of a sexual violence case there involving children and asked Project M to cover the story amid lack of attention from local media.

Membership manager Devina Heriyanto brought the proposal up during an editorial meeting, and chief editor Fahri Salam welcomed it.

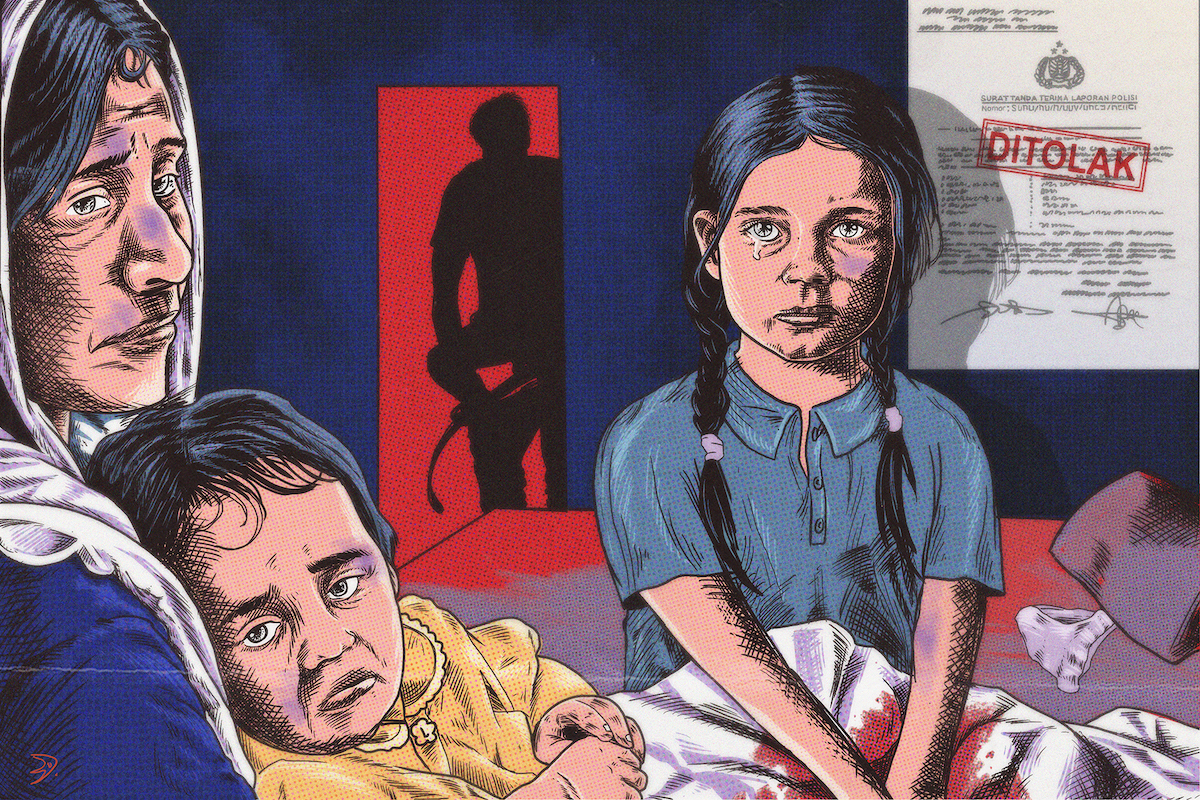

A few weeks later, we published an article based on the testimony of the child victims’ mother, whom we called “Ratih”, the title was “My Two Daughters were Abused. I Reported it to the Baubau Police, the Police instead Arrested My Eldest Child”.

The title was modeled after an older report, published in October 2021, that detailed a similar case in East Luwu: “My Three Children were Raped. I Made a Police Report, the Police Dismissed My Report”.

We reused our #NoUseReportingtoPolice hashtag, which had taken social media by storm.

There are a number of similarities between the two stories. Both began with mothers who discovered that their children, under 10 years old at the time, had been victims of sexual violence. Both incidents occurred in small towns in Sulawesi, and the mothers both filed reports with the police and local child protection office only to face rejection and reprisal. The mother in East Luwu, whose pseudonym for our report was Lydia, was called delusional, while Ratih’s eldest child, aged 19, was named a suspect.

These two stories were also the most physically and emotionally draining for us, especially for the editor, Fahri Salam, who found himself unable to sleep for nights after working on the two pieces. After publishing both reports, we were subject to digital attacks. We reached out to lawyers from a legal aid organization for the press (LBH Pers), requested emergency financial assistance from the Kurawal Foundation to protect our sources and provide them with access to safe houses, and carried out a series of other tasks to meet our moral obligations past the conventional delimitations of reporting. Project M co-founder and executive director Evi Mariani calls this practice: “beyond journalism”.

Rebecca Vincent, campaign director at Reporters Without Borders (RSF), said on Brave New Media by BBC Media Action that she appreciated that Project M had paid attention to the well-being of its sources.

The safety of our journalists and our sources is our utmost priority, and in order to ensure it, we continue to build networks of support. After a digital attack left our site inaccessible from Oct. 6 to 7, 2021, we announced that we would share the targeted article with other media outlets, student publications, bloggers, and civil society organizations to prevent Lydia’s struggles from being suppressed. The response was overwhelming. Over the course of four days, we received some 50 emails requesting republication. Dozens of media outlets republished the story, including VICE Indonesia, Suara.com, Tempo.co, Kompas.com and the IDNTimes.

Ignatius Haryanto, a journalism scholar, called it the “first time in the history of the Indonesian press” that an attempt to silence reporting was challenged by a republication movement.

A few days after our article was published, the then-chair and deputy chair of House of Representatives Commission III, Herman Herry and Ahmad Sahroni, demanded that the police investigate the East Luwu case transparently and help the victims achieve justice. In mid-October 2021, National Police Chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo held a video conference and asked regional unit heads to immediately remove, dishonorably terminate and punish police members who violated the law. He also encouraged all personnel to be open to criticism and self-reflection.

In December 2021, Listyo alluded to the #NoUseReportingtoPolice hashtag in two separate speeches, one at the Analysis and Evaluation Work Meeting of the General Supervision Inspectorate of the Police and the other at the Handover Ceremony of Positions and Corps of Reports for Senior Police Officers. He urged staff not to wait for a case to go viral before addressing it properly and to use public criticism for self-evaluation and improvement.

We have learned a number lessons from publishing these two reports, such as:

Our series on online delivery drivers was the first to go viral and have a real impact. From June 2021 to August 2021, we published 8 articles showcasing how hundreds of thousands of ride-hailing and courier drivers in Indonesia were being treated as “small screws” in a giant machine called “Big Tech”. While these couriers are much needed, they are also easily exploited and replaced with other “screws”.

The series was published, in part, to counter the wider media industry’s apparent lack of interest in the subject. Many publications are reluctant to cover even basic labor issues, and delivery drivers have grown further neglected amid Big Tech’s status as media darling and, increasingly, government darling. Tech companies spend large amounts of money on advertising and media partnerships to burnish their image.

The neglect of dissenting voices was apparent, for instance, during the merger of tech unicorns Gojek and Tokopedia, which sparked demonstrations by the former’s GoKilat couriers. The protests saw little media coverage.

The aim of the series was to examine the working conditions of online shopping couriers, who are considered drivers of economic growth in a sector that is predicted to flourish in the future.

Following the series’ publication, Trade Union 4.0 started a petition on Change.org calling for greater protections for delivery drivers. Project M had reported all the information used in the petition – demonstrating the information gap on the working conditions of e-commerce drivers. The petition now has more than 13,200 signatures, and people are continuing to sign it in 2023. A few months after the circulation of the petition, we were informed by the petitioners that Manpower Minister Ida Fauziyah had invited them to a hearing on the improvement of working conditions for couriers. Unfortunately, there was no follow up on the hearing.

Of the articles published in the Project M courier series, one had a particularly notable impact: Hanging by A Thread: I’m a Journalist, I Tried Being a Courier, I Lost My Breath. Our journalist, Viriya Singgih, worked as a delivery driver for e-commerce firm Shopee for two weeks during the pandemic.

The reception of the 11,000-word piece dispelled many myths about Indonesian readers, including that they didn’t like long, in-depth pieces, that they only read trivial news and that they didn’t want to pay for it.

Not only did Viriya’s post go viral beyond our expectations (Who would have thought an 11,000-word article could go viral?), it also brought in donations. When Viriya’s story was published in August 2021, we did not yet have a membership program, but from this one piece, we collected some Rp 6 million in donations in less than a week.

Beyond that, many readers circulated the piece on Twitter and Instagram, commenting that they would start giving tips to couriers, that they would now be understanding if a courier knocked on their door at 11 p.m., or that they would stop opting for cash-on-delivery payment, which puts couriers in a precarious position.

The series garnered 274,000 pageviews, 203,000 of which were for the journalist-turned-courier story. On Instagram, the series reached 249,000 accounts and enjoyed 20,500 engagements (likes and comments).

What is it that politicians, officials and businesspeople fail to address when they talk publicly about young people? Young people who have dropped out of school, are poor or have mental health problems. This is not to mention young low-wage laborers, young mothers and those who have to financially support their elders, are worried about the future or are burned out.

The #UnderprivilegedGenZ and #BurnedOutGeneration series consisted of seven and three articles, respectively. Our series aimed to fill the information gap on young people in Indonesia, who are told to be resilient in building start-ups, encouraged to be model consumers so that the economy grows and who are asked to vote for politicians who wear sneakers on the campaign trail but who do not offer support in school or on the job market.

In response to the two series, we received a number of invitations to speak on the condition of Indonesian youth. Permata Adinda was asked to speak at a TEDX event at the ITS Surabaya engineering school and became an expert resource person at a focus group discussion on youth held by the British Council. Evi Mariani also acted as a resource person on the Diary Dave podcast and was one of the speakers at IdeaFest 2022 to talk about the burdens of young people.

All three articles of the #GenerationBurnout series contain female main sources. Of the seven #UnderprivilegedGenZ articles, including one Ideas & Essays piece, three had female main sources and one a non-binary main source. The two series were created through the work of 16 female, male and nonbinary journalists, photographers, and illustrators. They managed to attract 187,350 page views.

In April 2021, we launched the Indigenous Peoples series to counter a dominant narrative that pushed for sweeping changes in the lifestyles of indigenous peoples under the guise of development. We were also seeking to bring indigenous voices to our readers, who are mostly urban youth. By February 2023, we had published 43 stories, four documentaries and three podcast episodes – the result of eight collaborations, including with local communities.

We helped share stories of the resilience of indigenous peoples and local communities in 18 provinces as they sought to address problems ranging from forest protection and agrarian conflict to COVID-19 prevention. The series caught the attention of our readers, who were looking for more positive stories, such as inspirational indigenous women figures and explorations of culinary and traditional knowledge. We began delivering these stories in 2022. A microsite, called the Window to Indigenous Women, was launched to present the stories of as many indigenous women as possible in a more interactive way. Going forward, we will work with local media to produce more stories for the microsite.

The dozens of articles in the #IndigenousPeoples series have attracted more than 172,000 page views and 205,000 interactions on Twitter and Instagram.

Our documentary film, Motherland Memories (Tano Na Uli, Hagodanganki), won the Indonesian Long Documentary Award at the Documentary Film Festival 2022 and was long-listed for Maya Award 2022. This film traces the life journey of Ompung Putra Boru, a Batak woman in her sixties in the area of Humbang Hasundutan, North Sumatra, as a wife, mother, healer and fighter for indigenous land.

In 2022, we began expanding our audience by producing collaborative multimedia products. We produced three films, one in collaboration with an indigenous novelist in East Nusa Tenggara, Felix Nesi; another with a young Dayak film crew from the Ranu Welum Foundation; and the third with Papuan Voices. Two were screened for a limited audience of 160 viewers. We also worked with three podcasters popular among young people – Benang Merah (Rara and Ben), Kejar Paket Pintar and Podluck Podcast Collective – to discuss our #IndigenousPeoples series, which can be accessed on YouTube, Spotify and other platforms. These podcasts have had 4,690 listeners on YouTube and other platforms.

For the first time, we are providing local products from the Adil Cooperative micro business in Yogyakarta as souvenirs for Kawan M members, as tokens of gratitude for their contributions.

The #IndigenousPeoples series helped us and our readers remember to look within and learn from indigenous peoples about how to tackle ongoing humanitarian and environmental crises.

Project M’s coverage has inspired readers to act in a variety of ways, including donations to sources and causes. An article about five early childhood education teachers in East Kalimantan who had not received their salary for eight months attracted 135 donors and brought in Rp 27 million in donations (Rp 14 million from the community and the remainder from crowdfunding platform Kitabisa). Donations amounting to Rp 20 million from readers were distributed to several other sources (the Jombang Women’s Crisis Center, underprivileged members of Gen Z in Yogyakarta, and organizations for people with disabilities in Bandung, among others). As of May 2023, we had helped mobilize a total of Rp 47 million in donations.

The initiative to establish an English version of Project M came naturally, as many of its founders and staff had worked at the Indonesian English-language newspaper The Jakarta Post. Project M’s English site is managed by Evi Mariani, who serves also as Project M’s executive director. Full-time managers have yet to be assigned for the English site, which explains its slower development than the Indonesian version.

Between May 2021 and December 2022, Project M English produced 38 English-language stories, including several Ideas & Essays pieces, as well as reports that were originally published in English and have yet to be translated into Indonesian. Several articles were also translated into English at the request of Impact Service partners/clients.

We believe the English site serves as a useful bridge between us and the international community, allowing our efforts to be amplified globally by introducing our vision and mission, as well as our work, to audiences across borders.

We are also open to international donations and have so far raised US$457. We sometimes receive messages of encouragement from individual donors. One of our most popular articles among international readers is “The Coal Oligarchs”, which was nominated for the International One World Media Awards.