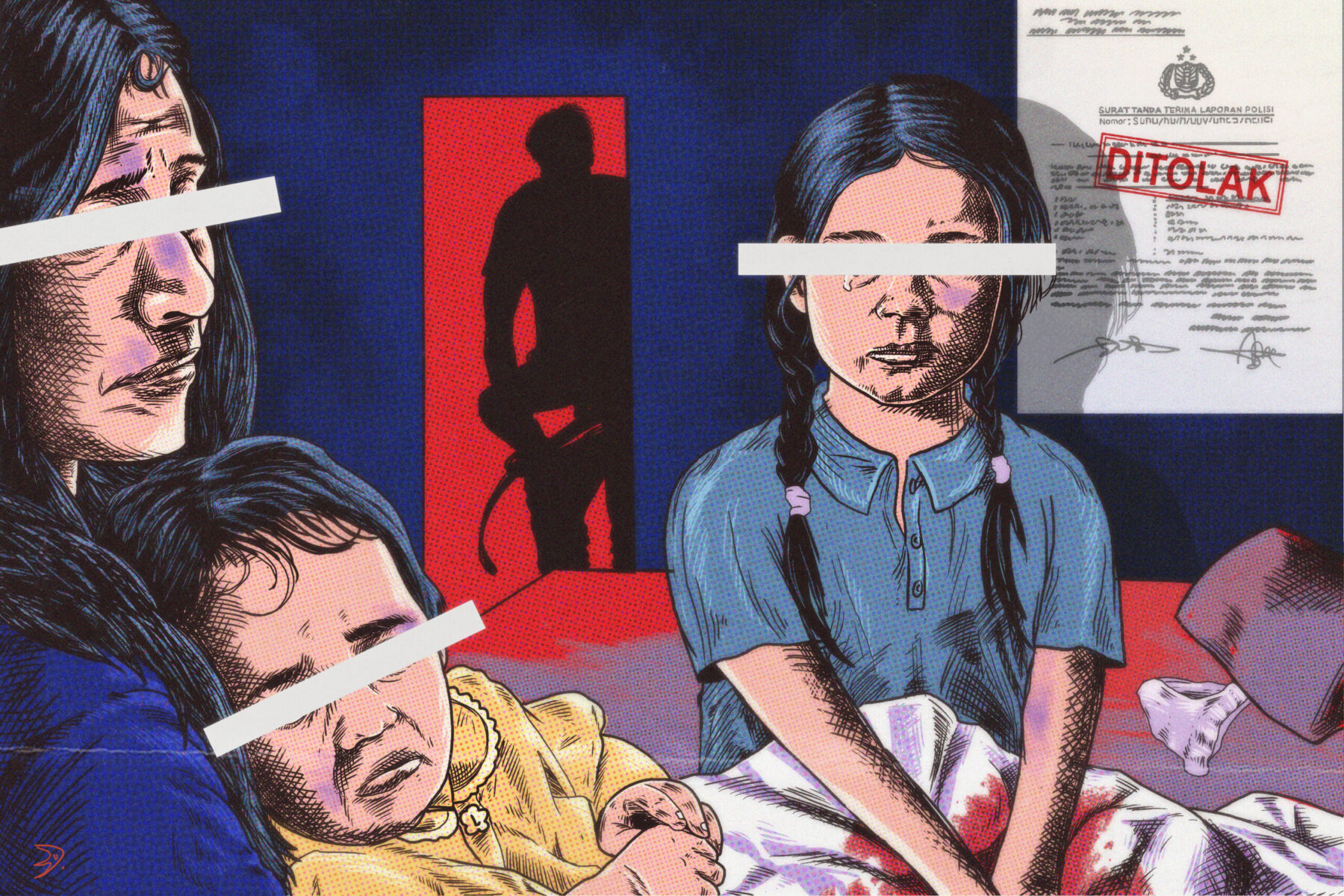

Content warning: This article includes descriptions of alleged sexual violence against children.

“If you write this story,” she says, “what will change?”

“We relied on the police. We reported it. But now, the perpetrator still walks free.”

In October 2019, Lydia (not her real name) reported to local police in Indonesia’s East Luwu Regency that her three children, all of whom were under 10 years old at the time, were raped by her ex-husband, their biological father. He was a civil servant working at the local http://projectmultatuli.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/5668A357-39CA-4B12-902A-DAE1F707FCD7-1.jpegistration office.

The police investigated her report, but according to Lydia’s lawyers, the process was plagued by manipulation and conflict of interest. Just two months after Lydia filed her report, the police closed the case.

The East Luwu Police also accused Lydia of fabricating the report to exact revenge on her ex-husband. Local officials, her lawyers say, sought to delegitimise the evidence she had collected against her ex-husband by claiming she was living with a mental illness.

After her divorce, Lydia became a single mother for her three children. They lived together in East Luwu, about a 12-hour drive from Makassar, the capital of South Sulawesi Province. The children lived with her, but her ex-husband would occasionally pick the kids up after school.

All seemed normal until Lydia saw suspicious signs: bruises on her children’s thighs when she helped them shower. The kids said they got the bruises from falling while playing around. Aside from the bruises, her children’s behavior also changed drastically. They became quieter and hit each other more frequently. They also lost their appetite, got dizzy and vomited frequently.

One night in early October 2019, Lydia was washing dishes when her youngest child shouted that their sibling felt pain in their genital area. Lydia approached the eldest child, hugged them from behind and gently stroked their shoulders.

“Kid, what was your little sibling talking about?” Lydia asked.

“Nothing, mamak [mother],” the eldest child said.

“I love you so much, I really do. If you have any problems, let me know. I will help and protect you. You should feel safe with me—don’t you?” Lydia said, trying to coax her child.

“Tell me please, kid. Mamak is not aware if you feel any pain. Do you feel sick?”

The eldest child stayed silent for a while before starting to cry, without tears. Lydia panicked. Choked up, the child said: “Mamak…Ayah na anu pepe’ ku.” Mother, father did something to my vagina.

Lydia cried and fell on the sofa. “Do not joke around, child.”

“It’s true, mamak. It’s true.”

Lydia then turned to her other two children: “Is it true, sweetheart?”

“Yes, mamak. He also did something to my butt,” her middle child said.

“Me too, mamak,” said the youngest child.

Lydia hugged her children, and they all cried together. Her head felt like it was going to explode. She wanted to scream. When Lydia tried to go to the bathroom to cry, her feet became weak and she fell.

Her children helped her crawl to the sofa. She was talking to herself and just started to gain consciousness when the children asked: “What happened to you, mamak?”

Lydia slowly collected herself. She checked her kids’ bodies and found wounds on their genitals and anuses. Later that night, she watched her children sleep. She was tired and confused. She could not sleep that night; it felt like the longest night of her life.

A ‘Fellow Civil Servant’

In the second week of October 2019, Lydia and her three children went to the Integrated Service Center for the Empowerment of Women and Children, known as P2TP2A, which is managed by the East Luwu Social Affairs Agency. The Indonesian government established these centers in provinces, regencies and cities to provide protection for survivors of violence and harassment who want to report their cases.

The center’s head, Firawati, met Lydia in a small room while the three children waited in the office’s playground. Lydia told Firawati about the sexual assaults allegedly perpetrated against her children and their claims that their father did it. Firawati said she knew the alleged perpetrator because he was a “fellow civil servant”.

The first thing Firawati did after taking Lydia’s report was call the alleged attacker, telling him that he had been reported for sexual assault. Lydia’s ex-husband then came to the P2TP2A centre, visibly angry with Lydia.

When asked why she called the alleged perpetrator before doing anything else, Firawati says she wanted the children to see their father to find out if seeing him would traumatize them. Firawati also says she only called him with Lydia’s consent.

“We’re fellow civil servants. I wanted to confirm [the trauma claim],” Firawati says.

“Guess what? All of the children rushed to their father and left their mother. They even reluctantly left the father when their mother called them,” she says.

Recalling Firawati’s version of events, Lydia is perplexed.

“How could she say something like that? On the day I reported my case and asked for assistance, Firawati instantly called the perpetrator and told him I came to her office with the kids,” she says.

“After the call, she accused me of teaching the children to vilify [their father as the alleged] perpetrator.”

“If I meet Firawati again, I’d like to see [her lie to my face].”

When her ex-husband came to the centre, he scolded Lydia and accused her of teaching the children to complain against him. He also accused Lydia of being incapable of taking care of the children.

Lydia felt cornered. Firawati told her to go home and wait for further information.

The next day, Lydia and her three children came to Firawati’s office again, as per Firawati’s request. An officer from the Family Learning Centre, a unit under the East Luwu P2TP2A centre, came to conduct a psychological assessment of the children. Lydia says she is not sure whether the officer was a certified child psychologist because he did not present his credentials.

The assessment found that Lydia’s three children “do not show signs of trauma” and that “their relationships with their parents are harmonious and [they get] enough attention”. Further, it said the children’s “physical and mental health are good”.

Found Nothing

Next, Lydia reported the alleged sexual assaults to the East Luwu Police. She went alone, as officers from the East Luwu P2TP2A centre said they were unable to accompany her. (Firawati says she was in a meeting with a local parliament member at the time; another officer says they were busy preparing to move into another office.)

The police recorded Lydia’s report on 9 October 2019. A woman police officer brought the three children to a community health centre—known locally as Puskesmas—where they underwent forensic physical examinations without their mother. After that, officers in uniform questioned them without Lydia or a legal adviser, social worker or psychologist present.

Police officers told Lydia to sign the investigation report, but she was prohibited from reading its contents.

Five days later, Lydia came to the police station to ask about her three children’s forensic examination results. She also brought a pair of pink underwear with blood spots to give to the police as evidence. A police officer told her that her report had been recorded and would be investigated by Police Inspector Kasman.

On Friday, 18 October, the police said the examination by the community health center “found nothing”. That same day, Lydia was interrogated by police without the presence of a lawyer.

“They questioned me about my daily life. The investigator said the questioning would be continued, and he would fill in the other parts because he had to attend Friday prayer,” Lydia says.

“They told me to sign the bottom of [a second] investigation report. I said I would sign it after the questioning resumed. However, the investigator forced me, and I eventually signed it. It was already noon, and I had to go home to prepare my kids’ lunch,” she says.

“When I think about it now, I was stupid for giving my signature.”

The following week, the East Luwu Police updated their investigation report. The report said the investigators had interrogated Lydia; her ex-husband, the alleged rapist; and their three children. It also repeated the findings of the 9 October forensic examinations, which police claimed had “found nothing”. Finally, it said police had scheduled medical and psychological examinations at Bhayangkara Hospital, the police hospital in Makassar.

Signs of ‘Child Abuse’

On 28 October 2019, one of Lydia’s children told her they were feeling pain in their anus. Lydia took several photos of the wound.

Two days later, she returned to the East Luwu community health center to request reference letters. One letter, contrary to what the police told her, said the 9 October health center examination had found that one of her children had a hemorrhoidal blood clot in their anus and showed signs of “child abuse”. Another letter said one of the children had abdominal and pelvic pain. The letters recommended further examination at a hospital.

Lydia says she brought her children to a private hospital on 31 October 2019 (the name of the hospital is being withheld for security reasons). There, a doctor asked the children how they received their wounds, and the children demonstrated what their father allegedly did to them. The doctor, Lydia says, diagnosed one of the children with vaginitis—an inflamed vagina—and constipation.

On 1 November, Lydia returned to the East Luwu Police station with the reference letters, the photos, a pair of underwear with greenish spots—a possible sign of infection—and a pair of leggings with blood spots. The police refused to look at the evidence.

“They said keep them, we don’t need those,” Lydia says.

The following day, an investigator called and told Lydia the follow-up examinations at the police hospital in Makassar had been scheduled for 6 November. On that day, Lydia received a call from her ex-husband, who told her he would stop sending a monthly allowance for their three children if she continued the investigation process.

Lydia ignored him, and she and a relative brought the three children to the police hospital in Makassar. Upon arriving at the hospital, Lydia and her three children were brought to the waiting room of a mental health clinic. They were then brought to an examination room, where they were met by four people: an investigator, a staffer from the East Luwu P2TP2A center and two people whom Lydia assumed were doctors. They did not introduce themselves to her.

Lydia discreetly recorded the two people psychologically examining her children. Her eldest child sat on the lap of the P2TP2A staffer, who was sitting on a sofa. While the children were being examined, one of the two people who she believed were doctors told Lydia to leave the examination room.

Next, Lydia and her relative were examined and questioned about the family’s mental health. The relative was asked about Lydia’s psychological state when she was a child and when she was married, and whether they had any family members with a history of mental illness.

The two examiners asked Lydia about her marriage and whether she had a “mental abnormality” before her divorce. She says the interview lasted only 15 minutes.

The hospital released the psychological examination results on 11 November. Lydia was declared to possess “systemic delusion symptoms that lead to permanent delusion”.

On 15 November, the South Sulawesi Police’s health department determined that Lydia’s children showed no abnormalities or signs of physical assault. However, Lydia did not see these results until months later, after lawyers from the Makassar Legal Aid Foundation (LBH Makassar) requested them from the authorities. Lydia says she does not know whether the two examiners at the police hospital physically examined her three children on 6 November because they had told her to leave the room. But other than the examination room at the mental health clinic, Lydia says they did not visit any other part of the police hospital that day.

On 19 December, the East Luwu Police sent Lydia a letter saying the investigation into her allegations was reviewed on 4 December and then closed on 10 December. The letter did not explain why the case was closed.

“The time span between the first report and the termination of the investigation was just 63 days. This is too short and doesn’t make any sense,” says Rezky Pratiwi, head of the Women, Children and Disabled People Division at LBH Makassar.

“This is a sexual assault case with children as the victims. Why did [the authorities] rush the process?”

Vindicated in Makassar

At the end of December 2019, Lydia and her three children got in a car and again drove for 12 hours to Makassar, the provincial capital. After a long and winding trip, they arrived at the Makassar P2TP2A centre, where Lydia hoped to re-report her case and secure justice for her children.

To her relief, the center in Makassar was nothing like the one in East Luwu. A staff person there referred her to LBH Makassar, which became her legal representative.

The Makassar services centre also provided psychological assistance for Lydia’s children. Its assessment report, which was carried out through observation and interview methods, stated that the three children “did not suffer from trauma but showed anxiety”. The report also said the three children told consistent stories about the alleged sexual assaults by their father, and their stories complemented each other. It also said their testimonies of being sexually assaulted by more than one perpetrator were consistent with what one of the children told Lydia when the East Luwu Police were investigating the case.

The children’s testimony was also supported by photos and videos Lydia took in October that year. The photos and videos showed signs of physical abuse on the three children’s bodies.

“The child psychologist who examined the children at the Makassar services centre is of the view that the sexual assaults did happen,” says Pratiwi of LBH Makassar.

Pratiwi believes the East Luwu Police’s investigation procedure was faulty from the start, from the first forensic examination on 9 October to how the children were questioned by officers. LBH Makassar lawyers also question the competence of the male psychologist who interviewed the children at the East Luwu P2TP2A centre.

The children should have been accompanied by their parent, as well as lawyers, social workers or other assistants, as stated in Law No. 11/2012 on the Juvenile Criminal Justice System, Pratiwi says.

“The East Luwu Police were not professional,” she says.

“The police instead focused on the mother, whom they said had a hidden agenda, and had her examined by a psychologist in an unlawful manner. They did not dig further into the children’s statement and did not examine other witnesses, such as their neighbours or people who know them, to find new clues.”

A Special Case Review

Lydia, along with lawyers from LBH Makassar, visited the South Sulawesi Police station on 26 December 2019 to request a special case review of the East Luwu Police’s decision to terminate the investigation into the alleged abuse of Lydia’s children. They submitted a letter along with photos of the three children’s wounds.

The lawyers also sent letters to the South Sulawesi Police on 10 and 13 February 2020 but received no response. Instead of replying to the lawyers’ letters, South Sulawesi Police spokesperson Ibrahim Tompo told journalists on 19 February that the police “had carried out an internal case review” and concluded that the termination of the investigation was legitimate and in accordance with police procedure.

On 5 March, the South Sulawesi Police told LBH Makassar that a special case review would be held on 6 March at 1 p.m. at the police station.

“The time frame was too short for us to prepare,” Pratiwi says. “The child psychologist who was supposed to accompany the children could not make it because they already had an appointment at that time.”

On 14 April, the results of the review were published. The South Sulawesi Police recommended that the East Luwu Police uphold their decision to terminate the sexual assault investigation.

In his office on the second floor of the East Luwu Police station, Police Inspector Kasman speaks proudly about his investigation into Lydia’s report.

“We have done the…forensic examinations. We even have the mother’s psychological examination report,” he says.

He declined to provide the case files, saying they are confidential. However, the findings of Lydia’s psychological examination at Bhayangkara Hospital in Makassar, which were also meant to be confidential, had already been leaked and reported on by local media in East Luwu. Many people there still believe Lydia is delusional and had fabricated the story.

“We know the case, but the mother is crazy, right?” one East Luwu resident says. “That’s why the case was closed.”

“If they said our http://projectmultatuli.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/5668A357-39CA-4B12-902A-DAE1F707FCD7-1.jpegistration process is faulty, that’s just LBH Makassar’s perception. We are professional. We do things in accordance with the law,” Kasman says.

Women’s Commission Tries to Reopen the Case

In July 2020, LBH Makassar sent complaint letters to several institutions, including the National Police Commission, the Indonesian Ombudsman, the head of the South Sulawesi Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Agency, the East Luwu regent, the Indonesian National Police chief and the National Commission for Eradication of Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan).

Kasman says the East Luwu Police had sent clarifications to such institutions, and “all is well”.

On 22 September 2020, Komnas Perempuan sent another letter to the National Police, the South Sulawesi Police and the East Luwu Police, demanding the investigation continue.

The investigation, Komnas Perempuan wrote, “should fully involve the parents, lawyers and the victims’ social assistants, and should provide safe housing, counselling and other facilities for [vulnerable] women”, among other things.

Further, the letter said, “the police need to coordinate with the Makassar Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Agency to facilitate the special requirements”.

The East Luwu Police have not complied with Komnas Perempuan’s recommendations. (South Sulawesi Police began reinvestigating the case on 10 October 2021, days after the original version of this article was published in Bahasa Indonesia by Project Multatuli.)

Pratiwi of LBH Makassar believes that police and officials from the East Luwu P2TP2A centre took sides with the alleged rapist.

“If the children have already testified, [the police] should follow the statements in the investigation. [They should] dig out the evidence first,” she says.

Still No Answers

With the investigation closed, Lydia decided she needed a change. Her children had been avoiding her house, and they cried when Lydia asked them to visit. She decided to sell the house, hoping to get rid of the memory of the sexual assaults that had upended her life.

Today, she still holds onto the evidence she collected over the last two years: the reference letters from the East Luwu community health centre, which contradict the police’s claims that the examination “found nothing”; the private hospital’s diagnosis of vaginitis and constipation; and several photos and videos showing the marks and wounds allegedly left by her ex-husband on the bodies of their three children.

The East Luwu Police ignored every piece of evidence Lydia brought to them. She is now left with many questions.

“If the police’s [forensic examination] results show no wounds, why did the police refuse the photos and videos I voluntarily provided for them?” she says.

“Why would my kids’ anus and vagina be wounded and swollen until it looks like white flesh?”

“Why did my children cry in pain every time they peed and pooped? Why do my children say their father is a bad guy and refuse to meet him now?”

“If the perpetrator is indeed innocent, why didn’t he come to visit his children and seek their explanation?”

“If people say it’s slander, why would they accuse their own father?”

“If I can’t find the answer to those questions, will the police help me? No, they won’t.”

Editors: Fahri Salam, Evi Mariani

The translation of this article from Bahasa Indonesia to English was made possible through the generosity of a Project Multatuli reader, Prima Wirayani. English editing was done in collaboration with New Naratif.

This article was first published in Bahasa Indonesia on 6 October 2021 as part of a series by Project Multatuli on police investigations and sexual abuse cases.