Bintang, what do you recall most about your mom and dad?

“Ibu [Mom], her cooking was delicious. I liked ibu’s ayam serundeng [fried chicken with shredded coconut].”

“Bapak [Dad], he liked to play with me, playing soccer and going swimming.”

A year ago, almost overnight, Bulan, Surya and Bintang, three siblings living in West Java, were orphaned. Their mother and father both died of Covid-19, their father in the evening, their mother the next day.

The three siblings were devastated. Nonetheless, they willed themselves to carry on. The many other children who have lost their parents and closest relatives to Covid-19 share similar stories.

When you miss them, what do you usually do?

“I don’t know. My sister [Bulan] cries,” said Bintang.

Do you also cry when you miss your parents, Bintang?

“No.”

I met the brothers and sister at their home in a densely populated neighborhood in Purwakarta, West Java, in late July. The two-story house had a mom-and-pop grocery shop.

While playing with a toy gun with soft rubber bullets, Bintang talked about Ibu and Bapak with an almost carefree air.

The 10-year-old boy chattered as if his grief had disappeared. He recounted memories of when Covid-19 broke out in his neighborhood and how painful it was to have his nose swabbed twice.

His hands were busy loading bullets and firing them at a target. Periodically, he shouted cheerfully when he hit the bullseye.

“Bapak is a birthday cake,” Bintang said all of a sudden. I turned to Bulan, the eldest, looking for an explanation.

“If someone had a birthday, Bapak always bought [a cake]. Our birthdays are in March, April and May. So it felt like he came home with a cake all the time. Even when it wasn’t anyone’s birthday, he would bring home martabak (large pancakes), or roti bakar (toast),” Bulan said.

***

They say crying is the most natural human response to dealing with loss.

Bintang, his brother and sister said, only did so once – when he first heard the news of his parents’ passing. Afterwards, he did not cry again. But his behavior changed. He became more irritable and would sometimes suddenly attack the people around him.

For a time, Bintang carried around a sharp weapon, they said. He ended up injuring his brother Surya, the second child.

Bulan called Bintang “possessed”.

During those episodes, his eyes were blank or sometimes closed like he was sleeping. But his body moved to attack anyone who approached him. Bintang also often became feverish and experienced shortness of breath afterwards.

This behavior occurred at memorial services marking certain periods of time since the children’s parents’ deaths, such as 40 days, 100 days and one year after.

The youngest child also had a tantrum while a foreign TV station was profiling them for a news story.

“Many people were watching. We had to sit, the camera was here, and he [Bintang] was not comfortable. He threw a ball at the journalist. They did not continue filming. It wasn’t aired,” said Bulan.

There is not much the siblings can do when Bintang “relapses”, as they call it. Usually, Bulan asks for help from neighbors, who recite prayers for him. When he calms down, Bintang seems not to remember anything about his rage.

Surya and His Silent Grief

One night, Surya dreamed his late mother was cooking his favorite meal. It was served to him before his father came home from work and asked Surya to give him a massage.

Surya woke up crying.

The 17-year-old Surya helps Bulan with the chores as much as he can. He looks after the shop and takes care of Bintang as well.

Surya has a hearing impairment and has difficulties talking as a result.

Surya and I did not communicate much the day I visited the siblings. This was not only because I was not good at sign language. Surya seemed not to want to talk much about his parents that day. We talked more through a messaging app later. He apologized for being slow to respond to my texts because he was busy with school and the shop.

Like Bulan, Surya said the toughest time after his parents’ death was the fasting month of Ramadan and the Idul Fitri holiday. Surya said the sadness was less acute these days.

“I’m more stable now. Not so sad,” he texted me.

I learned about Surya mostly from Bulan. At first, Bulan said, her brother often cried at night, likely missing his parents. But it was not for long. More typically, Bulan would see Surya staring in silence at nothing in particular.

Often, Bulan would see Surya confiding in a friend on video calls using sign language. Bulan said this was Surya’s way of releasing his sadness, apart from playing games.

“He’ll video call with his friend until midnight. He does that whenever he gets home from school,” said Bulan.

Bulan’s Dimmed Light

Bulan was not always as strong as she tried to appear. The 20-year-old university student was trying hard to hold on to life for the sake of her family. She had no choice but to brace herself, accept fate and shoulder the responsibility of being the head of the family.

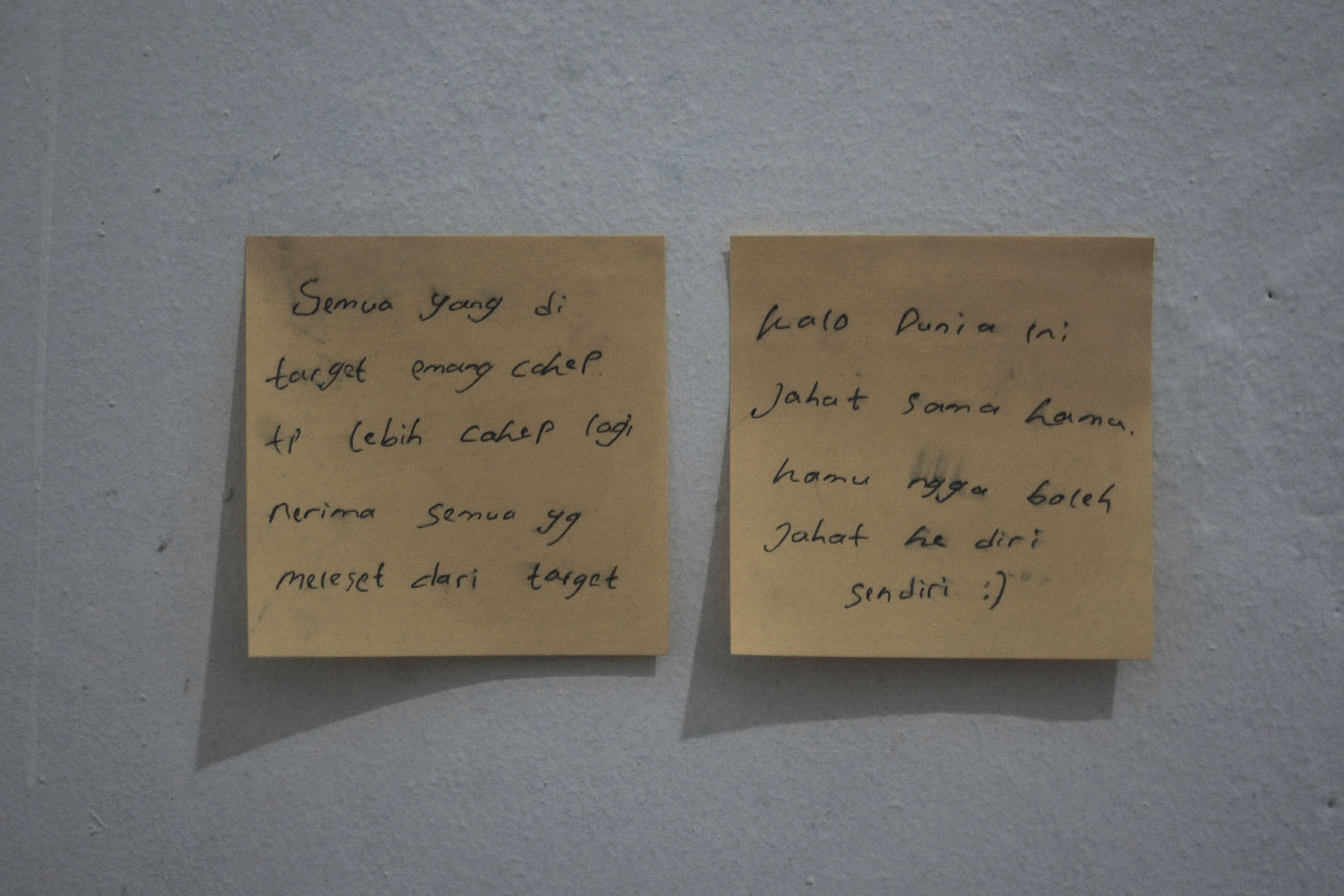

“You can’t stay sad for too long. The world keeps turning, life goes on. If I continue to be sad, then my siblings will too,” said Bulan.

I could hear the sorrow in her speech.

Bulan was by her mom and dad’s side when both were in critical condition in isolation. She insisted on accompanying them even though she knew she was at risk of contracting the virus.

At the time, the Delta variant was spreading in Java. Hospitals were packed, emergency wards had long lines of people waiting for treatment. Some died while waiting, some died at home. Bulan heard the news of deaths fill the hospital.

She was next to her father when he passed away and, hours later, was with her mother as well. Her mother asked Bulan for a hug before succumbing to the illness.

There was no time to grieve, as Bulan had to deal with the death papers and see to funeral arrangements. Afterwards, her hands were full taking care of her siblings, her mother’s shop, the family’s finances, the household and her studies.

She fought all the sadness and heartache. No time for tears, she said, tears would slow her down.

She stayed strong until she happened to have to visit the same hospital where her parents died.

“Bintang was seriously ill. I took him to the hospital and the feeling crept up on me. Everything was just like before. I was traumatized, I felt dizzy and nauseous. Now, whenever I hear an ambulance, I get a little scared,” said Bulan.

“I used to like watching movies or dramas about hospital life. Now I can’t. I tried once but immediately felt tightness in my chest.”

At that point, she became aware of her grief, she said.

This year, the siblings spent Ramadan and Idul Fitri without their parents for the first time. Bulan felt a heaviness in her heart, she missed them very much.

“I didn’t open social media because there are usually a lot of family photos during Idul Fitri. That’s okay, it’s just… I avoid triggers. So I went off social media for two weeks,” she said.

Five Counseling Sessions

The children’s parents were not originally from Purwakarta. Their mother was from Ngawi, East Java, while their father was from Jakarta. That is why Bulan, Surya and Bintang have no family in Purwakarta. Their nearest relatives are in Depok, West Java, and the others live outside the province.

Fortunately, they get a lot of support from the people around them.

The village head helped take care of the death certificates. Their father’s colleague helped with the funeral arrangements. And then there was the neighborhood unit (RT) lady who was always ready to help, as well as a neighbor they called Budhe (aunt) who would take care of Surya and Bintang when they were sick.

The siblings also received Rp 10 million (US$642) worth of food and money from the Purwakarta administration when they were orphaned. The West Java Social Assistance Agency has also provided Rp 400,000 on four occasions over the past year.

They are also receiving Rp 1 million per month from a zakat – Muslim alms – charitable institution.

Counseling sessions are another form of support.

Bulan said she and her siblings had seen psychologists provided by the administration. They went to five sessions each from August to December 2021.

Bulan said it had helped ease her grief a lot.

“I was so shocked that my parents had passed away that I couldn’t cry. When the psychologist came to see me, I burst into tears,” said Bulan.

The therapy for Bulan, Surya and Bintang took place separately with different experts.

Surya was accompanied by his teacher from his school for the hearing impaired who acted as a sign language interpreter. Bintang received therapy from a child psychologist. However, according to Bulan, the short period of therapy did not allow Bintang to overcome his behavioral issues.

Bulan suspected the problem was the difficulty Bintang experienced in expressing his feelings. She felt Bintang needed more help, not just from a psychologist or ustad (Islamic teacher).

“Bintang needs a psychiatrist. But I’m afraid he doesn’t want to open up,” said Bulan.

“He doesn’t do very well with strangers. Well, it depends on the person. He doesn’t remember anything once the anger subsides. One time, he was angry and then he went straight to sleep. He woke up saying, ‘How come I’m sleeping.’ He wasn’t aware at all that he had lashed out,” Bulan added.

Psychological ‘Time Bomb’

Children who have lost their parents to the Covid-19 pandemic have suffered multiple layers of grief.

Elvine Gunawan, a psychiatrist from the Limijati Mother and Child Hospital in Bandung, said loss was an abstract concept that was difficult for children to grasp. The younger the child, the more difficult it was for them to respond to the loss and express their emotions.

“Children can only see whether their mother is there or not. If they are told a concept of heaven, for example, their brains will hardly process it, and it will add to their confusion in defining loss,” says Elvine.

“That is why, when their parents die, children rarely cry. But there are behavioral changes or sudden sleep problems such as insomnia. This is because their emotional capacity is not yet at the level [that allows them to process the loss in a healthier way].”

A new mental health condition had been designated during the pandemic, Elvine said. In March 2022, Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) was added to the DSM-5-TR, the chief resource for the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders.

If the condition was not addressed properly, she said, the disorder could lead to major depression, especially in children who had come from happy families.

“Because there was previously an attachment built but then the child lost their object of love. Hence, the risk of depression is greater in those children,” said Elvine.

She commended the local administration’s provision of mental health services but said the efforts needed to be sustained for more than just three months, especially in Bintang’s case.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she said, could last for months to years. Therefore, a brief period of therapy could not address it properly. Policymakers and appointed mental health experts, she said, should attend to the progress of children who had gone through such traumatic experiences.

The government also needed to find new caretakers for children who had lost their families to Covid-19. Relatives, foster parents and orphanages were possibilities.

“If a child is already showing symptoms of a mental disorder and there is no intervention early on, later in adolescence they will have mental problems. It’s just waiting for the time bomb to explode,” she said.

The Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Ministry, according to media reports, said 32,216 children had lost their parents to Covid-19 as of Jan. 25.

Meanwhile, the West Java Social Assistance Agency recorded some 6,000 children who had lost a parent or parents to the illness as of September 2021.

A survey by national daily Kompas conducted nationwide in August 2021 found that 44.5 percent of respondents were worried that children who lost parental care would have their psychological and mental development disrupted, while 31.9 percent raised concerns about the fulfillment of the children’s daily needs and 18.1 percent raised issues of educational development.

Data Delays

Rita Pranawati, commissioner of the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI), said data on children who had lost a parent or parents to Covid-19 was being collected too slowly. As a result, protection efforts, including counseling, had not been optimal.

The Social Affairs Ministry had rolled out a social rehabilitation assistance program dubbed ATENSI for Covid-19 orphans. It consisted of seven services, including therapy and childcare.

“But then again, sometimes the children are not listed by the village administration. We must ensure they are cared for and make sure it does not turn into economic or sexual exploitation,” she said.

Dodo Suhendar, head of the West Java Social Assistance Agency, said the local administration had provided a number of trauma therapy services through the Social Welfare Center. He claimed that half of the 5,000 villages in West Java had community welfare centers.

I told him about the case of Bulan, Surya and Bintang receiving psychological assistance for only three months and that it had not been enough.

Dodo said the key lay with community leaders, from the RT head to the subdistrict head.

“The leading institution is the community welfare center. If there is no local center, create one in the village. If the village cannot handle it, ask for help from the district,” he said.

For safety and privacy reasons, the names of the three siblings have been changed in this article.

Translated by Alya Nurbaiti