On September 3, at least 130 Malay Sunni vigilantes attacked an Ahmadiyah mosque in Balai Harapan village, Sintang regency, West Kalimantan. The attack occurred after Friday prayers, during which the imam at a nearby Sunni mosque, Mochammad Hedi, delivered a speech in which he called the Ahmadiyah “blasphemous,” witnesses said. A local man named Zainudin can be seen on a video leading the mob, armed with bats and wooden sticks, as they burned down a warehouse and ransacked the mosque.

Because of previous threats, police had been posted to protect the Ahmadiyah community of 76 families. Despite desperate requests, the police did not intervene, possibly deciding to allow the attack on the mosque to avoid the chance that their intervention would lead to attacks on the Ahmadiyah villagers, or themselves.

There is now a serious risk of a new round of violence. This is particularly worrisome given the long history of ethnic and religious violence involving Malay, Indigenous Dayak, Madurese, and other groups – usually with complete impunity.

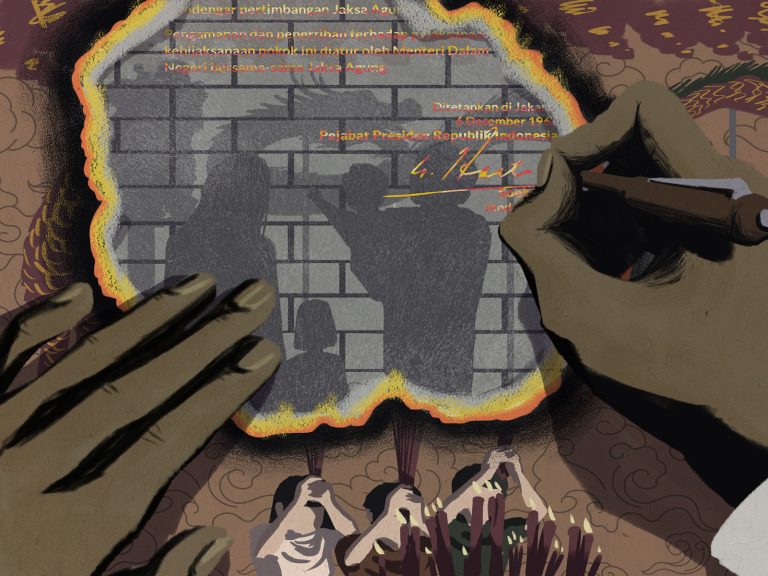

September 3 wasn’t the first time that the local authorities had capitulated to extremists. On August 14, they sealed the mosque, citing a 2008 decree issued by the government of then-President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono that ordered the Ahmadiyah community to “stop spreading interpretations and activities that deviate from the principal teachings of Islam.” The decree violated international law, which protects the right to freedom of religion. Yudhoyono acted in part under pressure from the Indonesian Ulama Council, a quasi-state institution that had declared the Ahmadiyah to be heretical in a 1980 fatwa and then reissued it in 2005.

The government also claimed that the Sintang mosque did not have a permit. But in remote areas like Sintang, most houses of worship, including Sunni mosques, do not have building permits.

But closing the mosque wasn’t enough for Hedi’s Malay Men’s Union (Persatuan Orang Melayu), which demanded that the government also demolish it. When that didn’t happen, on September 3 they took matters into their own hands.

The Ahmadiyah faith was founded in 1889 in Qadian, a town in what is now India’s Punjab, by a Muslim scholar, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. The community identifies itself as Muslim, though many Muslims consider the Ahmadiyah to be “deviant.” The Ahmadiyah are banned in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and some other Muslim-majority countries. Indonesia has approximately 55,000 Ahmadiyah families.

The Ahmadiyah community has also been targeted in other parts of the country this year. In Garut and Depok, both in West Java province, local governments also sealed Ahmadiyah mosques in May and October.

Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights has repeatedly called on the government to revoke the 2008 decree. According to Ahmadiyah sources, more than 30 mosques have been closed down since the 2005 fatwa, mostly in Indonesia’s 24 Muslim-majority provinces. In some cases, Ahmadiyah figures have negotiated with local officials and Muslim leaders to quietly reopen the mosques.

After media coverage of the September 3 events, the police arrested 22 men, including Hedi and Fathurruzi, charging them with destroying private property and provoking the attack. They are detained at the West Kalimantan police headquarters in Pontianak.

But the problem is far from over, as politicians and others try to make political capital from a highly inflammatory issue. West Kalimantan Governor Sutarmidji called on the Ahmadiyah “to return to the true path of Islam.” In a shocking development, he also visited Hedi and Zainudin in police detention in Pontianak on the day after they were arrested, posing for a photo with both and posting a video of the visit. On September 17, he ramped up the tension, issued a circular calling on the local government to “monitor to what extent the Ahmadiyah are obeying the 2008 decree.”

Meanwhile, an acting regent of Sintang has now issued a warning letter, demanding that the Ahmadiyah community demolish their mosque by November 5.

The Ahmadiyah in Sintang and around Indonesia fear that they are being targeted as part of a larger sectarian fight for political power among other groups.

The government of President Joko Widodo should make it clear that it will have zero tolerance for anyone invoking religion to commit violence against any group in Indonesia. The National Police should investigate the possible role of the Malay Men’s Union and politicians such as Sutarmidji. They should take steps to ensure that the trial of Hedi, Fathurruzi and Zainudin will be free of political pressure.

If the government is serious about Widodo’s claim that Indonesia is a moderate Muslim country, he should ask his cabinet, including Home Affairs Minister Tito Karnavian and Minister of Religious Affairs Yaqut Cholil Qoumas, to revoke the anti-Ahmadiyah decree and end all discrimination in law against religious minorities in the country.

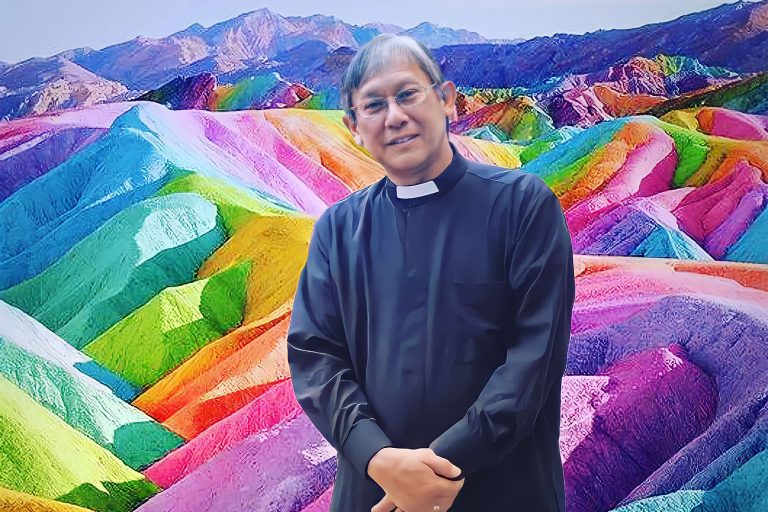

Brad Adams is the Asia Director at Human Rights Watch