Merauke is once again in the crosshairs of Indonesia’s food ambitions. A program that failed spectacularly more than a decade ago has been revived. This time, the government has enlisted the military and palm oil companies to clear vast forests, all in the name of food security and energy transition.

Around 10 a.m., Yakob Mahuze and Yuliana Basik Basik set off with their three children and two of Yakob’s cousins. They were headed to a swamp in Senayu Village to fish.

The group rode three motorcycles. Under the blazing sun, dust swirled around their tires and trailed behind them.

For over a month, it hadn’t rained in Senayu, which lies within the Tanah Miring District in Merauke Regency, South Papua. Hence, in places along the road, the scrub had turned to tinder, and some patches had burned, sending smoke curling into the air.

After parking their motorcycles, Yakob and his family walked along a two-meter-wide irrigation canal recently dug by soldiers, picking their way over the dried mounds of excavated earth toward the swamp.

More than a decade ago, when former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was still in office, authorities transformed this swamp and the surrounding land into rice paddies for Senayu residents.

The fields were planted once, but cultivation soon ceased. The land then lay idle for years, with large trees gradually reclaiming it.

Things changed in 2024, when the government stepped up its Land Optimization (Oplah) program in Merauke.

Through Oplah, the government aims to make idle or underused farmland productive again, including by preparing the land, building canals, as well as equipping farmers with machinery, seeds, and basic training.

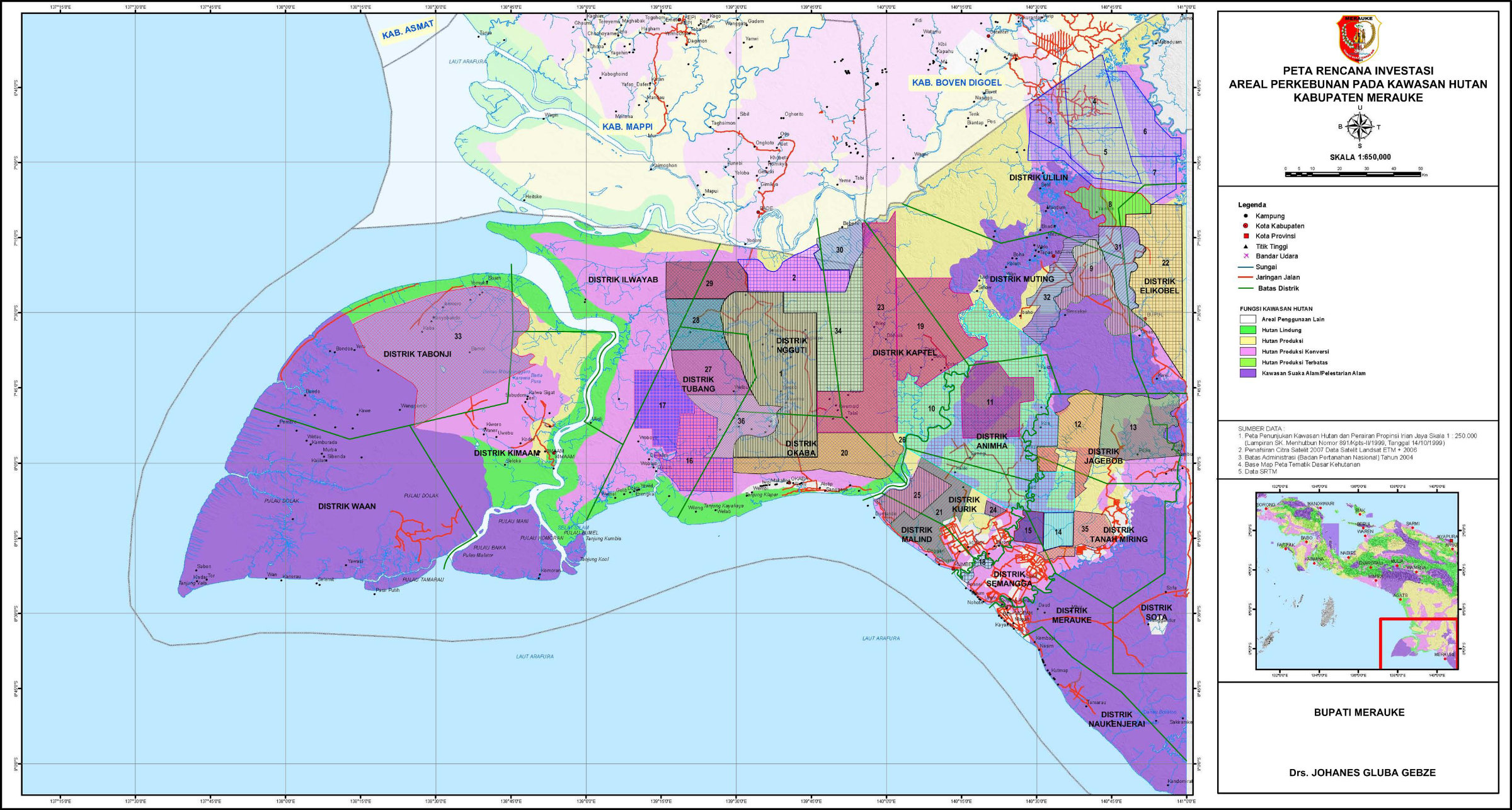

In 2024, with military support, authorities carried out Oplah on 40,000 hectares of land across six districts in Merauke: Tanah Miring, Kurik, Semangga, Malind, Merauke, and Jagebob.

That’s why a new irrigation canal ran alongside the path the Yakob’s family took to the swamp.

All this is part of the government’s plan to build a giant food and energy estate in Merauke, expected to comprise rice paddies, sugarcane plantations and mills, a bioethanol plant, and a biomass power station.

Alongside intensification, the government is bringing new fields under cultivation to realize the Merauke project.

Officials have repeatedly offered conflicting figures for the project’s scale. Some say Merauke will have 1 million hectares of rice paddies and 500,000 hectares of sugarcane plantations. Others go as high as 2 million hectares—applied to either rice or sugarcane, depending on who’s speaking.

However, one thing is certain: this project has forced many indigenous Papuans in Merauke to cede their customary lands and livelihoods amid reports of military intimidation and social coercion.

For instance, Yakob said he was pressured, including by individuals claiming to be “customary chiefs”, to surrender 5,000 hectares of his Mahuze clan’s ancestral territory for the planned sugarcane plantations.

“I actually didn’t want to give it up,” said Yakob.

“But I was under pressure from four villages, since the access route began on our customary land.”

The ground beneath Yakob’s feet carries the weight of history. His Marind ancestors won control of Senayu in ancient headhunting wars, through which tribes drew their territorial lines. That’s why Marind descendants, including Yakob, still hold authority over this land.

After the fighting ended, the Marind allowed other groups, including the Muyu and Awyu, to forage here. Over time, those communities settled in Senayu, building villages and drawing on the area’s resources.

As explained by Teddy Wakum, an advocate with the Papua Legal Aid Institute (LBH), the use of customary land for any purpose must be decided through deliberation, and the affected community members must agree to both the handover and the compensation.

This, however, appears to matter little to the authorities and large companies flocking to Merauke, who press ahead with the food and energy project regardless of consent or consequences.

The Rebirth of MIFEE

Merauke has long been earmarked for a large food production zone.

Even in the 1950s, when western Papua was still under Dutch control, an enterprise was set up to open and manage 300 hectares of rice paddies in Merauke’s Kurik District. With its flat terrain, abundant water, and fertile soil, the area was deemed well-suited to extensive agriculture.

In 2007, then-Merauke Regent John Gluba Gebze initiated the establishment of the Merauke Integrated Rice Estate (MIRE) to transform the regency into a national rice hub. Local and international investors were invited to take part in the project, expected to cover 1.9 million hectares or about 40% of Merauke’s area.

The project failed to attract investors, particularly due to the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.

Under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, MIRE was then reframed as the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE). By pairing large-scale cultivation of staple foods with biofuel crops such as sugarcane and oil palm, the project aimed to deliver not only food but also energy security.

Yudhoyono positioned MIFEE as a response to the global food emergency, saying that it would “feed Indonesia, then feed the world”.

MIFEE, eventually launched in 2010, was projected to cover 2.5 million hectares in Merauke, with total investment estimated at up to Rp60 trillion (US$3.6 billion).

Again, MIFEE faltered. Flawed project design and state-backed land grabs led to environmental damage, violations of indigenous rights, and widespread public protests.

That, however, didn’t stop Joko Widodo—Yudhoyono’s successor who served from 2014 to 2024—from trying to revive the project.

Widodo, better known as Jokowi, gained momentum in 2020. He leveraged fears of a food crisis amid the Covid-19 pandemic to push for food estate development, echoing the reasoning Yudhoyono had invoked more than a decade earlier.

In July 2020, then-Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto was tasked with leading the food estate program. In August 2022, a presidential regulation laid the legal foundation for its implementation in 2023, including in Merauke.

In November 2023, the Merauke Food and Energy Development Zone was added to the list of National Strategic Projects (PSN). In April 2024, Jokowi formed a task force for “accelerating sugar and bioethanol self-sufficiency” in Merauke, chaired by then-Investment Minister Bahlil Lahadalia.

Ever since, the project has moved ahead at full tilt.

A 2024 briefing paper from the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, citing an unpublished feasibility study by the state-owned surveying and consulting firm PT Sucofindo, suggests the Merauke food and energy estate may cover about 2.29 million hectares.

According to the study, about 1.18 million hectares are allocated for rice paddies, while the remaining 1.11 million hectares are for sugarcane plantations and associated facilities, such as mills and a bioethanol plant.

The Investment Ministry, however, said the sugarcane project alone would take up 2 million hectares. It stated the sugarcane area had been divided into four clusters, with the government now prioritizing Cluster 3 spanning 633,763 hectares. Total investment needed for this cluster is estimated at US$5.62 billion.

According to the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, 10 companies have secured recommendation letters for the release of forest areas totaling 541,094.37 hectares in Merauke, which are needed to establish the sugarcane plantations.

On the rice side, the project has drawn backing from Jhonlin Group, a diversified conglomerate with businesses in coal mining, oil palm and rubber plantations, and aviation, among others. The group is owned by South Kalimantan businessman Andi Syamsuddin Arsyad, often referred to as Haji Isam.

According to a senior military officer, then-Defense Minister Prabowo directly assigned Haji Isam to support the 1-million-hectare rice paddy project in Merauke.

Jhonlin Group subsequently procured about 2,000 excavators from China, and Isam said he personally oversaw field operations, including site surveys and land clearing for the port and the main road.

“This is a state duty,” said Isam in August 2024.

“In my mind, the question is how to make this 1-million-hectare rice paddy plan a reality and succeed within three years, without regard for profit or loss.”

The Cost of Switching Staples

Papua’s agricultural transformation first began decades ago.

For many Papuans, especially in the lowlands, sago was the traditional staple. They relied on it for generations, until transmigrants arrived and introduced rice amid the New Order’s push to expand paddy cultivation and standardize diets around it.

From 1964 to 1999, Merauke was a key destination for the government’s transmigration program on Papua Island. During that period, some 1,500 families, or around 7,500 people, were relocated to the Semangga and Tanah Miring districts.

Through interactions with transmigrant farmers, Marind and other indigenous Papuans then learned to grow rice and build supporting infrastructure, such as irrigation canals.

The pattern has continued in the years since. Yakob Mahuze, for instance, said he started rice farming in 2009 after his Javanese friends showed him the ropes.

“The Javanese really know their stuff, so we just follow their lead,” Yakob said.

“I don’t worry about it too much. When I’m unsure, I call them. if that doesn’t sort it out, they come straight to the fields to help.”

Senayu, Yakob’s hometown, borders transmigrant settlements such as Sermayam Indah, Ngguti Bob, and Bersehati.

Among the villages, Ngguti Bob stands out for its rice farming. Nearly every household there owns a hand tractor, said Rosidin, the village head who is Javanese. Even so, he added, working the paddies is no easy task.

Despite having the know-how, farmers are squeezed by high production costs and low yields. One hectare yields about 2.5 tons of milled rice, or 4 tons of unhusked grains. This is far below Java’s usual 6-8 tons of rice per hectare.

Moreover, farmers in Merauke typically harvest only twice a year, even though paddy fields generally can sustain up to four cropping cycles annually. One reason is the flat terrain, which forces irrigation to rely on pumps, leading to floods in the rainy season and parched fields in the dry.

Rosidin said he manages four hectares of farmland. But costs run so high that three hectares worth of revenue goes entirely to production expenses, leaving just one hectare to generate actual profit, he said.

“Farmers here really depend on banks or middlemen to get by. Even when they lend us Rp50 million [US$3,004], enough to farm five hectares, we need four hectares just to cover production costs,” he said, explaining why the farmers keep borrowing.

The workforce isn’t big enough to farm the available land either. Ngguti Bob has 1,357 hectares of productive rice fields, but only around 600 residents work as farmers—roughly one person for every two hectares. A single farmer can’t work two hectares efficiently with a hand tractor.

That’s why Rosidin questions the effectiveness of the Oplah program, which the government runs with military support to return idle or underused fields to productive use, including by building supporting infrastructure.

The problem is, he said, once the soldiers finish the infrastructure, farmers are left to cope with a manpower gap.

“What they did was helpful,” he said. “But is the program effective in the first place? Can the beneficiaries really make the most of the help?”

Now, as cultivation proves difficult and rice has become the staple food for many Papuans, local families often have no choice but to buy it amid debts to banks or middlemen.

At the same time, the government is pursuing a 1-million-hectare rice paddy scheme in Merauke, which many observers warn could push small farmers further to the edge.

The math simply doesn’t work.

The Land-Hungry Sugar Rush

Yakob Mahuze ceded 5,000 hectares of his family’s land to PT Global Papua Abadi, one of 10 firms currently developing Merauke’s sugarcane estate.

As Yakob recalled, PT Global Papua Abadi said it would “borrow” his family’s land for 35 years. Of the 5,000 hectares, 4,000 hectares would be operated by the company, with the remainder set aside as community plantations for the Mahuze clan in Senayu. The company, he added, also promised to cover the landowners’ children’s education.

As compensation, the company paid Yakob’s family around Rp700 million (US$42,227) in two installments. The money was then split among all family members.

“We received about Rp300 million first, which worked out to Rp11 million per person. Then came another Rp300 million, this time Rp16 million each,” he said.

“My younger relatives bought motorcycles. I put mine toward my kids’ education.”

The payout brought little comfort to Yakob. He still couldn’t bring himself to let go of the land.

Hence, Yakob refused when the company asked him for a larger area.

“We Papuans can’t turn our backs on [the land]. We still depend on nature. When we’re short on money, we hunt kangaroos or deer and sell what we catch,” Yakob said.

Furthermore, there is still no formal contract for the 5,000-hectare lease of Yakob’s family land.

“We don’t have any release papers,” Yakob said.

“They haven’t given us the final documents yet. That’s why I keep pushing them to provide the agreements.”

Eight years before the government announced the revival of Merauke’s food and energy estate in 2024, PT Global Papua Abadi had already been targeting local land.

Rosidin, head of Ngguti Bob Village, said the company tried to buy 200 hectares for sugarcane plantations, but the plan fell through because the soil was unsuitable.

“By 2023, they tried again. This time on a massive scale, right when the food estate became a national strategic project,” Rosidin said.

Suharja, head of Sermayam Indah Village, said a company representative visited him in the early stages of the project. The PR officer, whom he said looked like a military man, went directly to landowners.

PT Global Papua Abadi then began clearing the forest in June 2024.

According to satellite monitoring by the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, as of August 29, 2024, PT Global Papua Abadi had cleared about 2,016 hectares. The company planned to reach 5,000 hectares by the end of 2024.

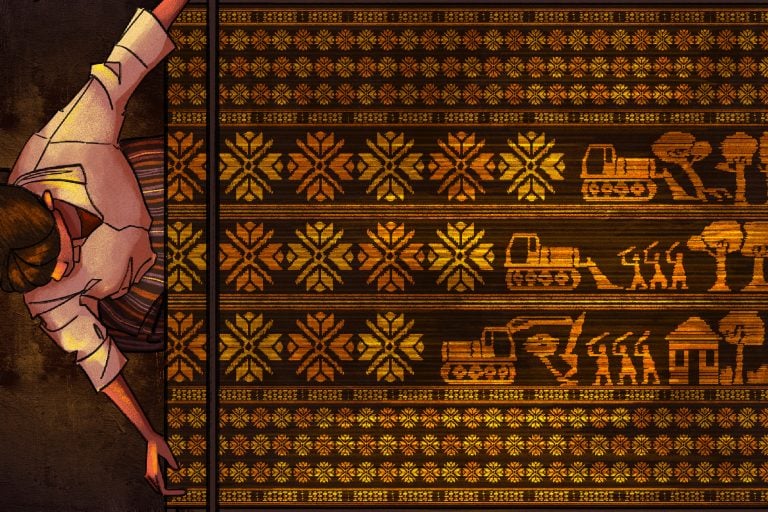

During a late 2024 visit by Project Multatuli to the company’s plantation site, heavy machinery ran around the clock, bulldozing forest and preparing the soil for planting. Tree trunks and root systems were stacked into massive block-like piles. The company employed many laborers, both Papuans and transmigrants.

Rosidin and Suharja have previously urged the companies to recruit workers from the affected villages, especially landowners, or at least simplify hiring requirements.

“Don’t make it complicated. Let them just provide ID and family cards. Have some compassion. Should landowners just stand and watch?” Suharja said.

As a landowner himself, Yakob was eventually hired by PT Global Papua Abadi. By joining the company, he hoped he could help secure jobs for his fellow villagers and relatives and ensure local participation in the sugarcane project.

“I’m in a comfortable position. I’m a hamlet leader with money. But should my other relatives keep searching for food every day? Keep fishing every day?” he said.

“We all need work.”

Sutami Amin, a researcher at the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, said indigenous communities in Merauke are undergoing massive change. As people now obtain most necessities from the market rather than from their own land, they have become increasingly dependent on cash.

“With these plantations, the companies control most of the land,” Sutami said. “This creates huge inequality in land ownership.”

Communities hope the companies will create jobs, he said, but there are no guarantees. In the end, it all comes down to whether people have the right knowledge and skills.

“Residents will end up as casual laborers. There’s no future in that, and labor law offers little protection for casual workers.”

Tycoons Behind Merauke’s Sugar Drive

A report by the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation shows that three businesspeople hold majority stakes in multiple companies now developing Merauke’s sugarcane plantations. They are Antoni, Angelia Bonaventure Sudirman, and Tan Keng Liam.

Antoni and Angelia together control PT Global Papua Abadi, PT Andalan Manis Nusantara, PT Semesta Gula Nusantara, and PT Agrindo Gula Nusantara.

Meanwhile, Angelia and Tan are majority shareholders in PT Berkat Tebu Sejahtera, PT Sejahtera Gula Nusantara, and PT Global Papua Makmur. Tan also co-owns PT Murni Nusantara Mandiri with David King.

Also in the group are PT Borneo Citra Persada, controlled by Silvia Caroline Fangiono, and PT Dutamas Resources International, jointly owned by Dudy Christian, Angell Madeleinne, Michael Angelo, and Rita Rushy.

In July 2024, then-President Joko Widodo attended PT Global Papua Abadi’s inaugural sugarcane planting ceremony, accompanied by businessmen Martua Sitorus and Martias Fangiono, as well as Martias’ daughter, Wirastuty Fangiono.

Forbes ranked Martua as the 18th richest person in Indonesia in 2024. He co-founded Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil company.

In 2013, Wilmar announced a planned joint venture with the Noble Group, a Hong Kong–based commodities trading firm, to develop oil palm plantations in Papua, but the project reportedly never moved forward.

Since 2013, however, Wilmar has held permits for 200,000 hectares of sugarcane plantations in Merauke.

According to the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, Martua is linked to Tan, who also holds shares in several companies involved in Indonesia’s National Strategic Projects (PSN).

Tan serves as director of both Katingan Timber Group and PT Wahana Samudera Sentosa, an industrial forest plantation company operating in Merauke. Both firms are controlled by Wilmar.

Wilmar has faced repeated allegations of environmental violations. According to Friends of the Earth, the company was responsible for illegal deforestation and the destruction of peatlands in Riau. A 2017 report by Greenpeace Indonesia also identified Wilmar as a major contributor to deforestation in Indonesia.

Meanwhile, the Fangiono family controls vast plantation holdings and allegedly influences the global palm oil trade through their Singapore-based company: First Resources. The family also plays a significant role in Merauke’s sugarcane expansion.

Angelina, who holds shares in seven companies involved in the Merauke sugarcane project, is Martias’ granddaughter. Silvia, who owns PT Borneo Citra Persada, is Martias’ wife.

In 2007, an Indonesian court sentenced Martias to 1.5 years in prison and fined him Rp346 billion (US$20.85 million) for corruption linked to oil palm land clearing.

His son, Ciliandra Fangiono, became CEO of First Resources in 2009.

According to a report by Yayasan Pusaka Bentala Rakyat, the Fangiono family owns at least five oil palm plantation companies in Southwest Papua through the Ciliandry Anky Abadi (CAA) Group, with concessions totaling 138,010 hectares.

In 2017, CAA Group was alleged to be behind the clearing of orangutan-habitat rainforest in Central Kalimantan.

On paper, First Resources, CAA, and the Fangiono family’s other plantation company, PT FAP Agri, seem to have no connection. However, a collaborative investigation by The Gecko Project shows business links and overlapping control within a complex conglomerate structure involving individuals and family members across these firms.

This corporate network appears in Merauke’s sugarcane project as well.

A Tempo investigation found that First Resources obtained a sugarcane concession and the right to build a bioethanol plant from PT Global Papua Abadi. First Resources also secured concessions from PT Andalan Manis Nusantara, PT Semesta Gula Nusantara, PT Borneo Citra Persada, and PT Dutamas Resources International.

When contacted by Tempo, First Resources denied any relationship with the other companies. Meanwhile, Project Multatuli’s requests for comment to PT Global Papua Abadi went unanswered.

‘I won’t give up a single inch of land’

Many local residents initially welcomed PT Global Papua Abadi’s arrival to develop sugarcane plantations in Merauke, hoping it would reduce unemployment and bring new income to the village.

However, serious concerns have since emerged over flooding and damage to rice farming systems.

“Farmers are definitely worried,” said Rosidin, head of Ngguti Bob Village. “Everyone’s already concerned. Something is bound to happen.”

In mid-May 2024, floods hit Merauke’s Salor Village, submerging hundreds of homes and rice fields. This was allegedly due to damage to natural water-absorption systems in the oil palm estates upstream from the village.

Now, large-scale sugarcane clearing threatens to trigger similar problems.

Two rivers run through the area: the Kumbe to the west and the Maro to the east, with the latter closest to residential areas. In the rainy season, the Maro’s water level typically matches the surrounding swamps. Residents say they want companies to install proper flood-control systems.

“The real issue is what the implementation will look like,” Rosidin said. “They usually panic only after something happens.”

Suharja, head of Sermayam Indah Village, voiced similar concerns. Even before the sugarcane plantations arrived, rainfall in upstream areas like Jagebob District often caused flooding in Sermayam’s rice fields.

Now, with these sugarcane plantations, the flooding could get worse.

As explained by Sutami Amin, a researcher at the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation, sugarcane companies have severed indigenous communities from their natural environment and drawn them into the plantation system.

This new reality doesn’t always work in the communities’ favor, and many are not fully aware of its implications.

“We’re living in an economic system, this new capitalism, where not everyone benefits, where prosperity comes at the expense of other people’s suffering,” he said.

Sophie Chao, an anthropologist in the University of Sydney’s History Department, writes in her journal that the government and corporations often cast Merauke’s traditional food systems as primitive.

Top-down development policies, coupled with sustained propaganda and campaigns promoting a national food system, have been used to justify land seizures, forest clearing, and agribusiness expansion. This, she argues, hurts local communities’ ability to access food.

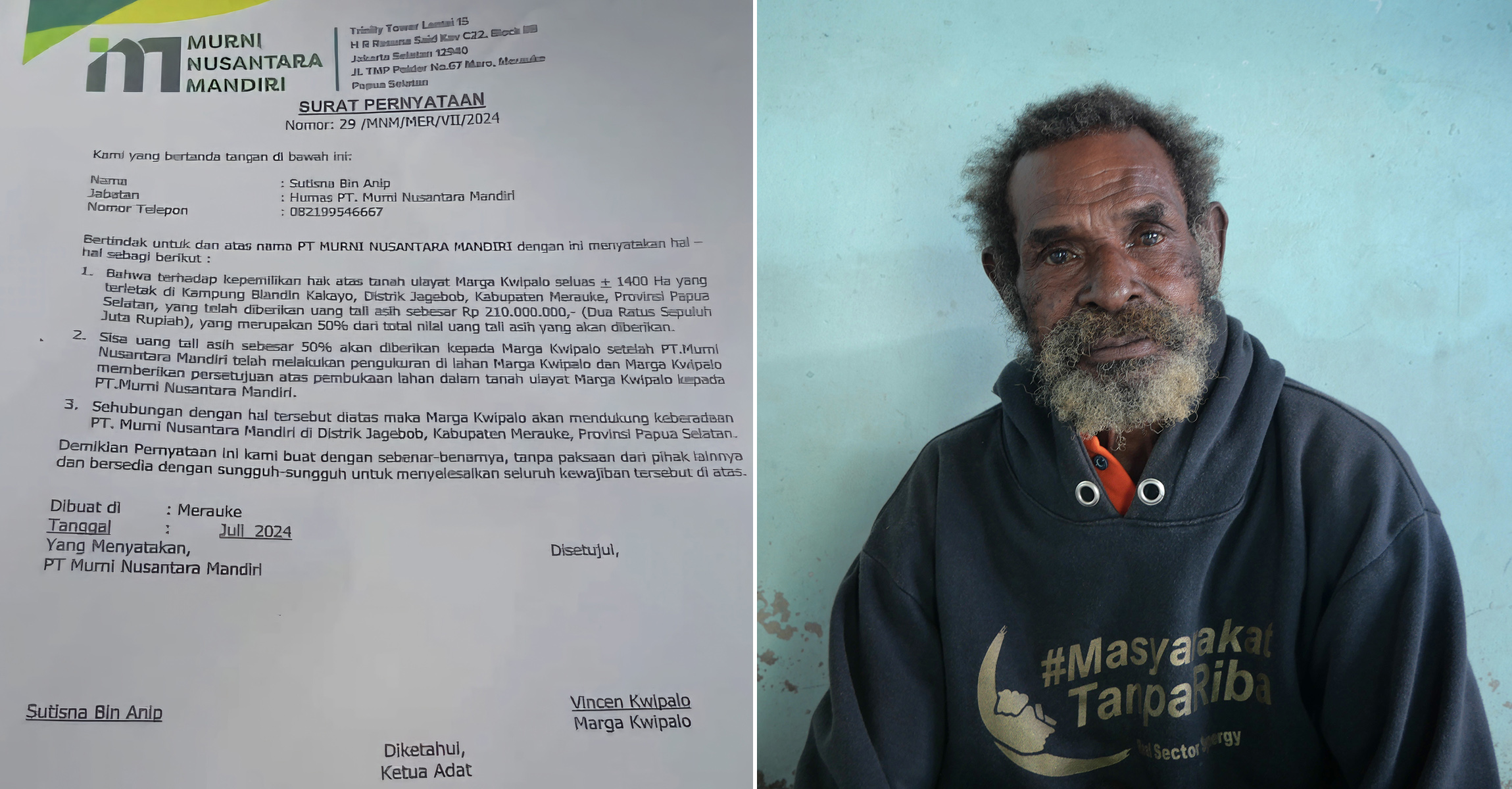

Several companies involved in Merauke’s sugarcane project are still processing the release of indigenous customary land rights. One of them is PT Murni Nusantara Mandiri.

Vincen Kwipalo, one of the landowners in PT Murni Nusantara Mandiri’s concession area, is determined to keep his family’s land.

The military’s village supervisory non-commissioned officers (Babinsa) have repeatedly approached Vincen, but he has consistently said no.

He has hired the Papua Legal Aid Institute (LBH) to represent him against the company and to challenge its unilateral boundary surveys on his ancestral land. He has also joined other communities calling on military commanders to withdraw troops that are intimidating landowners who refuse to sell.

Vincen has heard what happened to other customary landowners whose areas have already been taken over. None of the stories end well.

“Who doesn’t want the next generation to thrive? We all do. But how? Let’s not drive ourselves off a cliff,” he said.

“That’s why, for me, I won’t give up a single inch of land.”

This report was produced in collaboration with the Pusaka Bentala Rakyat Foundation. The original Indonesian piece was translated by Anne Parisianne. The English-language editor was Viriya Singgih.