The cold night winds do not dissuade the residents of Wadas village, Purworejo, Central Java, from making their way to the musala (prayer room). Hundreds of men and boys fill the room to hold a mujahadah, a prayer session for aid in their struggle.

For the umpteenth time, they pray to God and seek the strength to hold on to their ancestral land. Wadas residents believe God has blessed their fight, that fighting for nature, the environment, and life is also a form of devotion.

The residents are praying for protection and, now, a miracle, as the government is turning their land into an andesite quarry. The quarry will supply materials for the construction of the 169-meter-high Bener Dam, which is to be the highest in Indonesia and the second-highest in Asia. The villagers are worried that the mining operation will take away their livelihoods and food supply, dry up their wells, decrease the value of their land, and increase the risk of landslides.

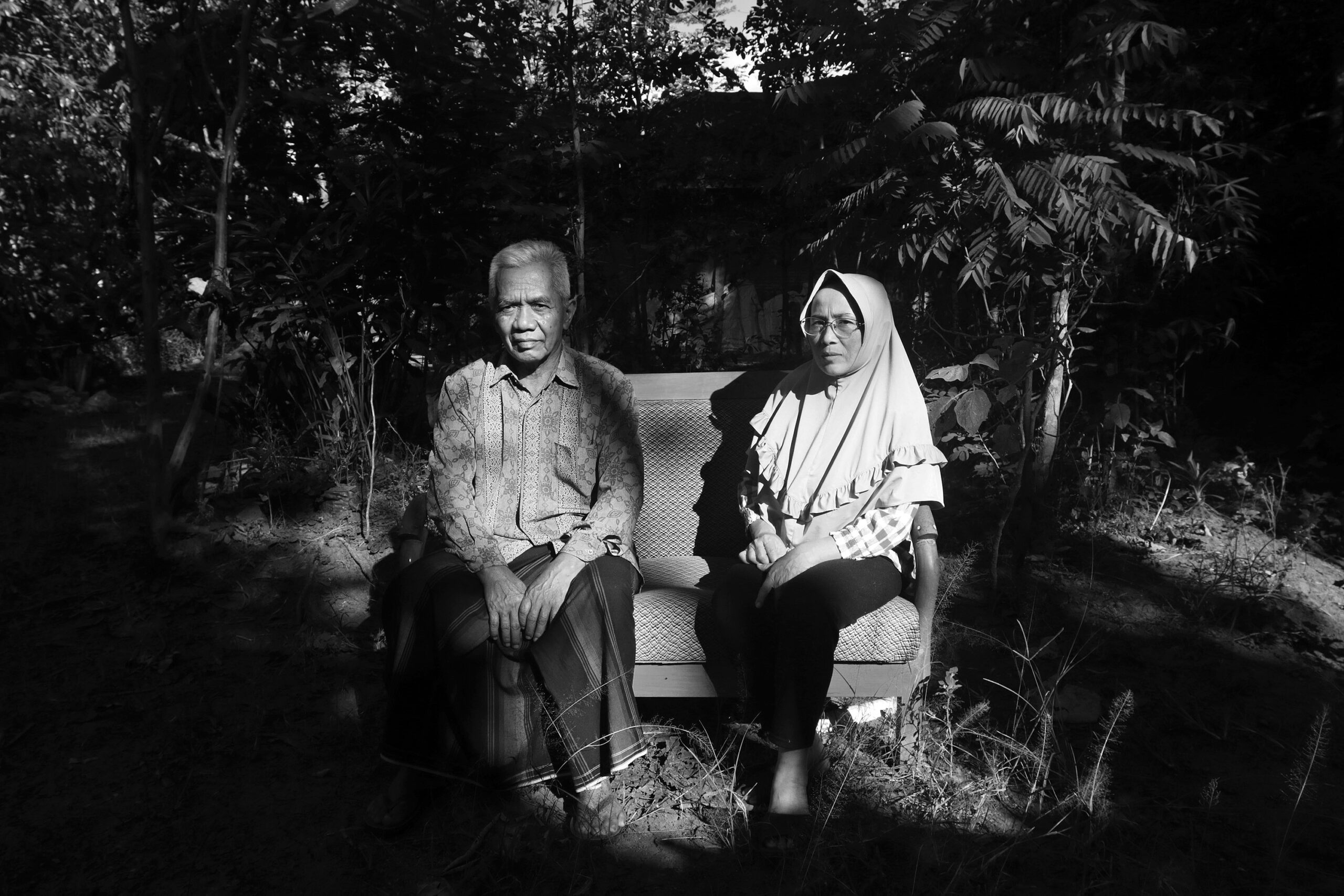

Insin, a 75-year-old retired teacher, says the problem started in 2013 when the residents discovered drilling activities in several parts of the village. None of the residents had been informed about the drilling.

“Whenever we asked them, they just said that they were only construction workers and didn’t know what the drilling was for. We feel that local leaders and policy makers have lied to us. [The leaders] did not have the conscience or sense of responsibility to protect nature for their children and grandchildren,” said Insin, who is now a farmer.

Yatimah, the 50-year-old leader of the Wadas women’s community, shares the same concern. She says the community does not oppose the dam project but rather the andesite mining operation on residents’ agricultural land. Wadas sits in a fertile region for the cultivation of kemukus (cubeb), kencur (aromatic ginger), peanuts, para rubber trees, coffee, vanilla, and durian.

Suroso, 45, and his 14 family members live in three neighbouring houses. He has been informed that the houses are on what is to become the quarry.

“It feels unsettling. Where should we live? This is our ancestral land. We don’t want to give it up,” he said.

Mbah Marsono, 62, feels uncertain about the community’s future. Many of the residents have passed the productive age, making it difficult for them to adapt to changes. These ageing farmers hope they can still make a living from their farmland, which they plan to eventually bequeath to the next generation.

The residents have united under the People’s Movement for the Wadas Village Environment (Gempa Dewa) to consolidate their fight and their prayers, as regional and national leaders have turned their backs on the community. Through prayer, the residents are raising their spirits for the uphill battle.

“I will never sell any of my property to anyone at any time,” Insin insists.