The stigma attached to the Tobelo Dalam tribe in Halmahera in North Maluku, Indonesia, has made them a moving target, with the government branding them as criminals. They are struggling as nickel mines encroach on their traditional land and sources of food.

BOKUM was over the moon. He was dressed sharply, in a long-sleeved white shirt, light brown pants, and a hat that covered his long hair. He was wide-eyed, with a big smile behind his mask.

That afternoon, on Jan. 24, 2022, he walked out of the front gate of the Class II A Correctional Facility in Ternate, North Maluku. Bokum had served eight years behind bars, shorter than his initial 15-year sentence.

He finally breathed the outside air and was embraced by his friends who had supported him from the beginning of his case.

He was supposed to have been released from prison along with Nuhu, his cousin. Unfortunately, Nuhu passed away while incarcerated in March 2019.

Bokum and Nuhu were part of the Tobelo Dalam tribe, often called O’Hongana Manyawa. They live in the Akejira forest area, part of the Trans SP III administration in Woejarana village, Central Weda, Central Halmahera regency.

Both were imprisoned for the murder of two people from Waci village, South Maba, East Halmahera – Masud Watoa and his son Marlan Matoa – a crime both denied doing. The incident occurred in the forest between Dote village and Waci village.

Bokum and Nuhu’s sentences caught public attention. Both denied committing the murder, and the event has left many questions about the nature of the deaths. It was not the first time a murder occurred in the forest.

Accused

On July 3, 2014, Abu Thalib Bakir, along with six companions, including Masud and his son, went to the forest area of Waci village. They were looking for agarwood. After five days went by and they had failed to find any, they decided to go home.

On their way back home, they encountered six people who they believed were part of the Tobelo Dalam tribe. The six people had similar features, thick beards, and tied-up straight, unruly hair. Some had shoulder-length hair, and others had shorter hair. They all wore sabeba (traditional tribal loincloths) and held arrows and long machetes.

The six people from Waci village ran away on impulse. Marlan, Masud’s son, who was seven at the time, fell. The court documents referring to the investigation report (BAP) by the East Halmahera Precinct Police dated Aug. 6, 2014, say that Marlan was then tortured by a group referred to by the police as an “isolated tribe”.

Masud turned back to help Marlan. He managed to lift his son, but an arrow hit him on the back of his right foot, according to the report. He ran for three more steps and then fell.

Abu Thalib was also hit by an arrow, but he was still able to run with his three companions toward a cliffside. He heard the screams of Masud and his son from behind.

They ran toward Waci village to ask for help. The people of Waci were shaken by the event and went to the police.

The chronology of events was reported by Abu Thalib to the investigators from the East Halmahera Police.

Six months into the investigation, the police could not find any traces of the perpetrators, even though they had looked into the people of the forest where the event allegedly occurred. The victims’ families and the Waci people were pressuring the force to make a quick arrest. They were worried that a similar event would happen again.

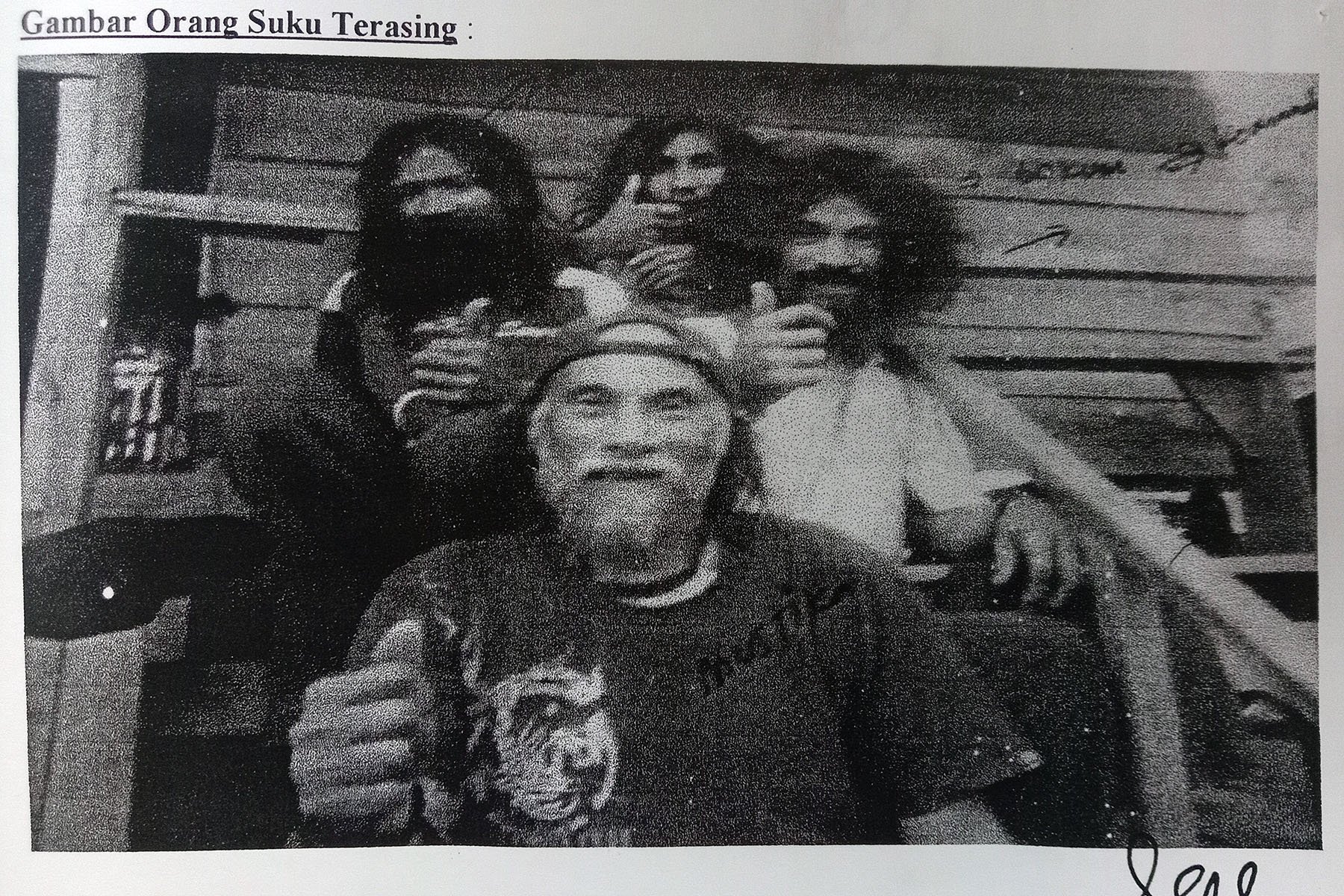

Around this time, rumors about the event spread on social media. Photos depicting the Tobelo Dalam people that were taken in the past by researchers and nonprofit organizations for research purposes and charity events began to resurface, including a photo of Bokum and Nuhu, along with the Tobelo Dalam tribe in the Akejira forest area.

The police used three of these photos to match the descriptions from Abu Thalib of mustached, thick bearded men with tied, long and unruly hair – features that were common among the people of the Tobelo Dalam community.

“I know two people from the four of the isolated tribe in the photos the investigator showed me. It is true that the two people from the isolated tribe […] were the suspects in the murder,” Abu Thalib told investigators.

Irregularities in the Accusation

The claim led to the arrest of Bokum and Nuhu, who were asleep in a house owned by resident Oti Maliong in Woejarana village in March 2015.

Neither resisted arrest. Nonetheless, one police officer hit Nuhu on the hip with the butt of his rifle. At the police station, both later claimed, they were forced to falsely confess to the murder in Waci forest.

During the trial, legal authorities provided evidence of 13 arrows, called witnesses from the surviving victims, and showed a photo of the two suspects that Abu Thalib claimed had committed the murder.

Maharani Caroline, the defense attorney for Bokum and Nuhu, said there was something off with the evidence and witness accounts. The testimony of several witnesses, including Abu Thalib’s account of meeting the Tobelo Dalam tribe but only remembering the face of Bokum and Nuhu from the event, seemed to be fully fabricated, she said.

“We are certain that it is part of a fabricated story that supported the police’s narrative so that the police force could avoid getting pressured and cornered by the family and the Waci village people to find the murderers,” said Maharani, as stated in a pledge read during the trial on Sept. 4, 2015.

The defense team said that they did not find any facts or motives to support the accusation that Bokum and Nuhu had committed the murder. They arrived at the conclusion that Bokum and Nuhu were not responsible for the murder.

However, the judge ruled against them. Bokum and Nuhu were declared guilty and sentenced to 15 years in jail. After five years behind bars, Nuhu passed away, possibly as a result of an untreated illness.

Customary Borders

Ngigoro Dulada squatted in front of a villager’s house in Saolat village, South Wasile, East Halmahera, in early September 2022.

The 57-year-old was the cousin of Bokum and Nuhu.

He was a direct descendant of the Tobelo Dalam tribe, although, since he was 7, he lived in the village outside of the Akejira forest with his mother. The move happened a year after his father, Dulada, passed away in the late 1970s. He remembered his mother saying that she could not raise a child in the forest without the support of a husband.

Ngigoro was his nickname when he lived in the forest. When he moved to the village, his name was changed and listed in the civil registry as Gerson. However, his close relatives still called him Ngigoro.

He is now fluent in Indonesian. He went to an elementary school but did not finish. He now has gray hair and is partially bald, but his physique has remained lean and strong. He can still enter the forest at his age, exploring the space where he was born and raised.

Although he is largely settled in the village, he often visits his family who lived in the forest, including in Akejira, where Bokum and Nuhu lived with their family.

After his two cousins became embroiled in legal troubles, Ngigoro regularly visited his family in Akejira forest. He knew in detail how the problem affected the lives of Bokum and Nuhu’s wives and children, as they lost the support of the man of the household, who in their culture usually hunted in the forest for the family.

“[Bokum’s] wife and child had to hunt to survive. They tried to survive on their own, but it is difficult,” said Ngigoro.

While Nuhu was in jail, his wife and kids, too, had to find their own food in the forest. His wife could not hunt and gather sufficiently on her own, and the children were too small to help. The last thing Ngigoro heard was that Nuhu’s family was out of the forest and his wife was working as a domestic helper in North Halmahera.

Ngigoro was also present when Bokum was released from the correctional facility. He told Bokum, “When you arrive there [in Akejira], you cannot trust those people. Don’t trust them. Don’t repeat the same foolish mistake.”

Ngigoro served as a witness for the defense during Bokum and Nuhu’s trials. He was sure that the cousins were not the real perpetrators and thought that there was no way Bokum and Nuhu intentionally crossed the forest from Akejira to Waci.

He added that members of the Tobelo Dalam tribe could not stray beyond their traditional hunting borders without the permission of the customary owner of the adjacent forest area. If they did, they could be killed.

“They have a custom in that forest. You simply cannot disrupt the area of other [tribes]. If you disrupt other people’s areas, you are simply asking to get killed. That is how it has been from the beginning to this day,” said Ngigoro.

The Tobelo Dalam people have borders between their communities that they call madedengo. These are part of what keeps the groups distinct from each other.

It could take days to reach the forest in Waci, where the murders took place. In that area live the Tobelo Dalam Woesopen tribe.

Even if the tribe’s people were the perpetrators, Ngigoro was certain that there would have been a trigger for the violence. The villagers might have violated the rules of the forest people, such as killing forest animals, tampering with the forest people’s plants or burning forest people’s houses, he said.

No Tobelo Dalam people would kill without cause, Ngigoro claimed.

Living within the Community

The Tobelo Dalam tribe lives within the forest area of Halmahera Island. Syaiful Majid, a sociologist and a researcher from Muhammadiyah University in North Maluku, classified the Tobelo tribe into two general groups: O’Hoberera Manyawa, the coastal Tobelo people, and O’Hongana Manyawa, the forest Tobelo people.

Tobelo Dalam communities occupy a number of areas, including one community in the Tidore Islands, five communities in Northern Halmahera, six communities in Central Halmahera, and 14 communities in Eastern Halmahera.

Each community, called a hoana, has a separate living area. For example, in the forested area of Central Halmahera, the living spaces are within the Kaurahai forest area, Tubublewen, Sangaji, Ida, Dote, and Akejira.

The coastal O’Hongana Manyawa people live as nomads. Even so, they overwhelmingly remain within their customary area.

Syaiful said it was incorrect to call O’Hongana Manyawa people “primitive Togutil” because of their subsistence way of living. “Togutil” is another name for the Tobelo Dalam tribe but has a negative connotation, as it can also mean “backwardness”.

The local wisdom and customs that guided their everyday lives, Syaiful said, had strong social meanings and emerged from a deep belief system and set of values.

The provincial government’s settlement program for the Tobelo Dalam tribe was not successful, and they slowly returned to the forest.

Syaiful knew Bokum and Nuhu personally. He used to live with them when he was researching the Tobelo Dalam people in Akejira in 1996. He had his own nickname there, Ahi, which means someone the tribe regards as one of their own.

Syaiful also accompanied Bokum and Nuhu during their trial and became part of their legal advisory team. He expressed disappointment at the judge’s guilty verdict.

“If I must tell the story of Bokum and Nuhu’s trial, instinctively, reflecting on my humanity, I have to say that it was not humane. The trial did not consider the human factors of it.”

The trial was also carried out in the Indonesian language. Bokum and Nuhu could only speak the language of the Tobelo Dalam people, and during the trial, both said they did not understand what was happening or the reasons why they had been brought before the court.

The court did provide them with a translator. However, according to Syaiful, the translator did not have sufficient knowledge of the language and customs of the Tobelo Dalam people.

Munadi Kilkoda, the head of the North Maluku chapter of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), said the verdict had neglected human rights.

Munadi, who also accompanied the defendants during the legal process, agreed that the true perpetrators deserved to be punished. However, he did not think Bokum and Nuhu were responsible for the murder, as it did not even happen in their tribal territory. He thought this fact was odd.

“‘We did not know Waci,’” said Munadi, quoting Bokum, as he recalled one of the conversations that took place in court.

The legal team called several witnesses in an effort to have the defendants’ sentences lessened. One witness, Oti Maliong, insisted that Bokum and Nuhu no longer wore sabeba and always wore regular t-shirts and shorts at the time. He said he had never seen either of them carrying a long machete or bow and arrow.

Yustus Regang, a village supervisory officer (Babinsa) in Weda, also supported Oti’s statement. He said that on July 2, 2021, Bokum and Nuhu had helped him and Oti go to Akejira forest to gather wood. Three days later, two people from the Tobelo Dalam tribe came to the camp of mining company PT Weda Bay Nikel (WBN) to get their portions of rice, fish, instant noodles and other staple items.

This statement was also supported by Ahmad Yani, a contractor at PT WBN who oversaw logistics and aid for the tribal people in Akejira. He said that each week, Bokum and Nuhu would come and collect their aid and that July 6, 2014, was no exception.

Ahmad had worked at PT WBN since December 2010. He knew Bokum and Nuhu very well. He knew that if they came to take their allotments of food in the afternoon, they would spend the night near the mining company’s camp. He also knew that whenever they were at the mining camp, tools such as machetes would be stored far away.

“If it was true that the defendants were the murderers, it would be very illogical that they would still go around the villages, go to the Weda Bay nickel company to collect their staples,” said Maharani Caroline, the attorney of Bokum and Nuhu.

Interactions with Tobelo Dalam People

Two weeks before I met Ngigoro, I met Melkianus Lalatang in Woejarana village, Central Weda, Central Halmahera. He knew intimately where Bokum and his family frequented in the Akejira forest.

My intention at the time was to meet Bokum, who had been released from prison a few months prior. However, my expectations were too high.

“It’s too far away. They are all up at the springs. One day won’t be enough to make the trip,” said Melki.

“Except on Saturday or Sunday – maybe they’ll be at church then. Or maybe they will need something and go out,” added Rina Makawimbang, Melki’s wife.

I did not end up meeting Bokum or his family. Their living space was too vast, and they were dozens of kilometers away from the village.

Melki knew the tribe’s people well, especially the ones who lived in the Akejira forest area. Melki’s relationship with Bokum and Nuhu had started when he decided to move to Akejira forest in 2007, along with his wife and children, for almost four years.

Before he moved, Melki often encountered the tribe’s people when he went hunting or set up traps in the Akejira forest. He said he was never once attacked or bothered by them. In contrast, the Tobelo Dalam people began slowly to interact with Melki and eventually treated him like a close relative.

For dozens of years after getting acquainted with the tribe, Melki did not see the wives or children of the Tobelo Dalam people. There is a tradition in the tribe of keeping wives and children out of the view of strangers, partially to keep them safe from other tribes.

Unexpectedly, the tribe set aside this practice when Bokum and Nuhu, who were the backbone of the tribe’s hunting outings, were arrested. The wives and children of the community were forced to leave the forest to seek food. They even visited Melki to ask for provisions.

“The whole time Bokum was in prison, I saw them. Rice, salt, I gave them everything,” said Melki.

The problem was that the women from the tribe did not speak the local lingua franca. They could only understand the insular Tobelo Dalam language. Rina said that when the women needed something, they would use sign language to get their point across.

“So they have known us for a while. My farm in the forest is like their own farm. They often take the bananas, the sweet potatoes,” said Rina.

During the time Bokum and Nuhu were incarcerated, Melki and Rina did their best to help the Tobelo Dalam families in Akejira obtain food. Moreover, the nickel mining firm’s food donations were suspended for a time because of issues within the company.

Eventually, Rina taught Bokum’s wife and other tribal women to plant cassava, sweet potato, and other plants to ensure the availability of food for them in the future.

“I taught them how to farm,” she said.

Several days before I spoke with the couple, Rina said Bokum and his wife had asked for cassava seeds. They were getting used to planting crops that they had not previously known or managed in the forest.

Mining Expansion

Based on his research, sociologist Syaiful Majid believes that the accusation that the Tobelo Dalam people are “murderers” is a stigma perpetuated by outsiders.

He says it is an extension of other claims by security forces or the government that the tribe members are “primitive Togutil”, “uncultured” or “stupid”.

Bokum and Nuhu’s cases were not the first or the last of their type. In 2019, six people from the Tobelo Dalam tribe were accused of a similar murder in the Waci forest. The event occurred in Patani forest, Central Halmahera, in 2021. At the time, three people were mutilated by an unknown person with a traditional weapon. The police then narrowed the perpetrator profile to one of the “Togutil tribe”.

“The stigma that the Tobelo Dalam people are murderers is not true,” said Syaiful.

The Tobelo Dalam people would only kill another person if their social system was violated, said Syaiful. As long as this did not happen, they would not dare to commit murder, he claimed. During his research, Syaiful had witnessed how people looking for agarwood did not suffer any violence when they encountered the Tobelo Dalam people.

Syaiful suspected that the killings in the forest on Halmahera Island were triggered by fights over living space. The forest is not always dominated by the Tobelo Dalam tribe. The villagers around the forest often use the area to trap prey and take other natural products.

“Maybe there are living areas within the forest that some people fight each other over,” said Syaiful.

“This string of murders happened during the nutmeg harvest season. That leads me to think that this murder was triggered by a fight over [nutmeg gathering] space within the forest.”

He was not sure members of the Tobelo Dalam tribe were even involved.

“The forest is their home. How can they disturb [the peace] within their own home. It’s impossible.”

When the women of the Tobelo Dalam community give birth, they are required to plant a tree, a custom that is not part of the life of modern people or settled villagers.

“That they help conserve the forest is quite outstanding, because they think of the forest as their home,” added Syaiful.

Munadi Kilkoda from AMAN said intrusions into the living space of the Tobelo Dalam people had become larger in scale. The food stocks of the Tobelo Dalam people were being depleted as a result of the expansion of mining and industrial areas within the forest.

This could be seen, he said, from the extent to which Bokum and Nuhu collected rice, fish and instant noodles from the nearby mining company. The prey and foragable foods in the forest were almost gone.

Several large companies are encroaching upon the forest, including PT Weda Bay Nickel (WBN), PT Tekindo Energi and PT Position. All three mine nickel ore, which is in high demand amid the rise of electric vehicles, which use nickel for their batteries.

The Geoportal of the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry shows that PT WBN has a mining concession that spans 45,065 hectares and includes parts of East Halmahera regency and Central Halmahera regency. PT Tekindo Energi has a permit for mining that covers 1,000 hectares in Central Halmahera, while PT Position has a mining operation permit (IUP) for an operational area of 4,017 hectares in Eastern Halmahera.

“It’s all their operation. It’s not a small area; the mining [operation] is quite huge. So this automatically means that there will be no prey passing by. The treasures and the farms in that area are finished,” said Munadi.

Ngigoro concurred that the industrial expansion had severely affected the tribe’s living space. The forest area once inhabited by the Tobelo Dalam tribe had been almost completely cleared.

“They have nothing now,” he said.

Translation: Farida Susanty

This story is part of #IndigenousPeople series.