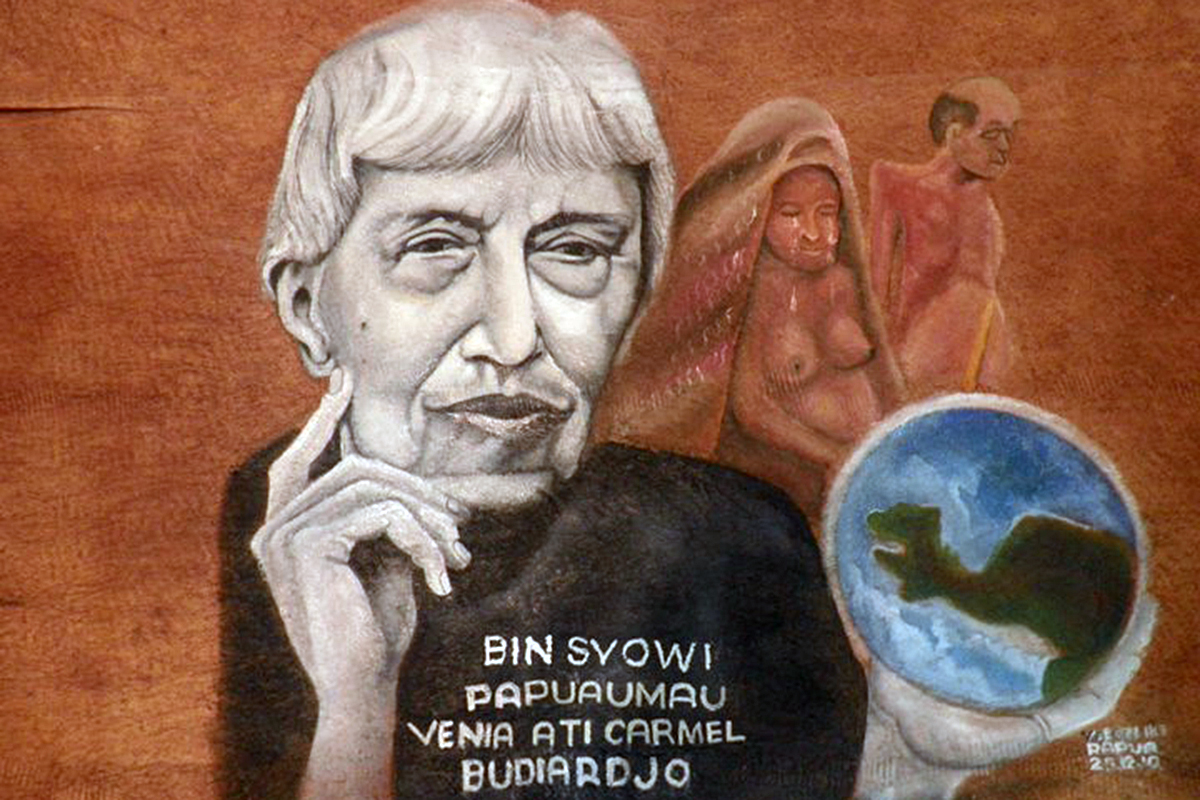

In August 2005, I visited Carmel Budiardjo, then an 80-year-old human rights campaigner, in her London townhouse. We talked on the second floor, which was also the office for Tapol, the human rights organization that she helped set up in 1973 (in Indonesian, the word “tapol” stands for tahanan politik – political prisoner).

In the 1970s, Tapol led a global campaign to release the approximately 30,000 political prisoners held by the then-dictator, Soeharto. It prompted US President Jimmy Carter in 1978 to call for the prisoners’ release. Soeharto released almost all of them, keeping several dozen jailed in Jakarta. Tapol later became a leading voice on rights issues in Indonesia, particularly in the troubled areas of Aceh, East Timor and West Papua.

Carmel, who passed away in London on July 10 at 96, is among the very few people whose work in the region has been recognized in both conservative Muslim areas, like Aceh, and predominantly Christian areas, like East Timor and West Papua. Her efforts to release and then help political prisoners were immeasurable. In 1995, she received the Right Livelihood Award in Sweden. In August 2009, East Timorese President José Ramos-Horta, who had helped campaign for East Timor’s independence from Indonesia, presented her with the Order of Timor Leste. She also received awards from independent groups in Aceh and West Papua. She is probably the only person to receive such wide recognition from so many diverse groups in this archipelago.

In 2005, she and I talked about why many people living in Java, Indonesia’s most populous island and home to the capital, were oblivious to the disparities between Java, as Indonesia’s “core”, and the “outer islands” (which the Dutch colonists called the Buitengewesten, or Outer Territories). “It also applied to me when I lived in Jakarta in the 1950s,” she told me. “Only when I left Indonesia in 1971, I began to understand the problem. I was caught up by the concept of the liberation of West Papua in the 1960s. I had to be outside Indonesia to begin to think about the reality of Indonesia. West Papua is not necessarily a legitimate part of Indonesia.”

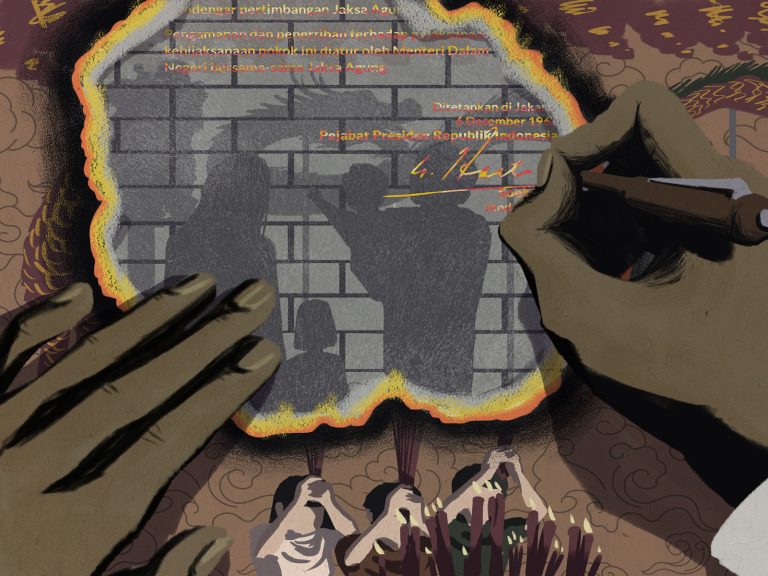

Carmel also spoke about the underlying causes of human rights abuses in Indonesia. The notions of a nation-state and a sense of equal citizenship are very thin in Indonesia. Many dominant identities, whether as Muslims or ethnic Javanese, are often used to discriminate against and repress minorities, which frequently led to violence. “I am not an advocate of breaking apart Indonesia,” she told me. “But in West Papua and Aceh, there are strong feelings of injustice and their own nationalisms. West Papua was an international issue. The Act of Free Choice in 1969 was an absolute fraud.”

Carmel was born in London in 1925, between the two world wars, into a Jewish family, whose anti-fascist views influenced her left-wing politics. In 1947, she met Suwondo Budiardjo, a young Indonesian official, in Prague. They married and moved to Jakarta in 1952. She worked as a translator and later wrote economic analyses and speeches for both President Sukarno and the Indonesian Communist Party. When General Soeharto toppled Sukarno in 1965, her husband was jailed for “political offenses” and spent 12 years in prison without trial. Carmel herself spent three years in detention, also without trial, before her deportation in 1971. She wrote about these years in her heartbreaking memoir, Surviving Indonesia’s Gulag.

When she returned to London, her townhouse became a gathering place for activists from all backgrounds. Over Chinese food, she told me about the need for raising awareness about nation building and the stories of political prisoners, as well as about her hopes for Timor Leste, a new nation that ended Indonesia’s occupation and had no political prisoners.

Though much time passed since we last spoke, all of our conversations are still relevant to the challenges Indonesians and others face today. Carmel was a towering figure. As James Ross, a longtime Human Rights Watch colleague, wrote after hearing of her passing, “If there were a human rights movement Hall of Fame, Carmel would have been one of the first inductees.”

Andreas Harsono works for Human Rights Watch. He is the author of Race, Islam and Power: Ethnic and Religious Violence in Post-Suharto Indonesia (2019), in which excerpts of his interview with Carmel Budiardjo were first published.