Syafri looked exhausted when I met him in Daan Mogot, West Jakarta, on a recent hot afternoon. Leaning against the wall, Syafri had a blank stare on his face. The cigarette in his right hand was close to burning out.

“I get stressed not driving, bang [brother],” he said. “But what are you gonna do? It is what it is. It’s not fair, really.”

Syafri is an online motorcycle driver, or ojol in Indonesian. He delivers goods. However, for the last two days, Syafri hasn’t worked–not because his motorbike broke, but due to a new policy from the ride-hailing application that pays him.

For couriers like Syafri, the merger in late May of two Indonesian decacorns–the e-commerce platform Tokopedia and the superapp Gojek–should have opened a new, brighter chapter for what the firms call their “partners”, a.k.a., the independent contractors who have helped GoJek grow and develop since its founding in 2010.

GoJek, which bills itself as Southeast Asia’s leading technology group, merged with Tokopedia to form the GoTo Group, which it claims is Indonesia’s largest technology group and largest digital consumer platform. GoTo has two million drivers, 100 million active users each month, and a gross transaction value of over US$22 billion in 2020, according to its website.

In a press release, GoTo Group President Patrick Cao said that GoTo Group would comprise 2 percent of Indonesia’s GDP. “We’re going to create a lot more employment and income-earning opportunities as our company and the economy expand.”

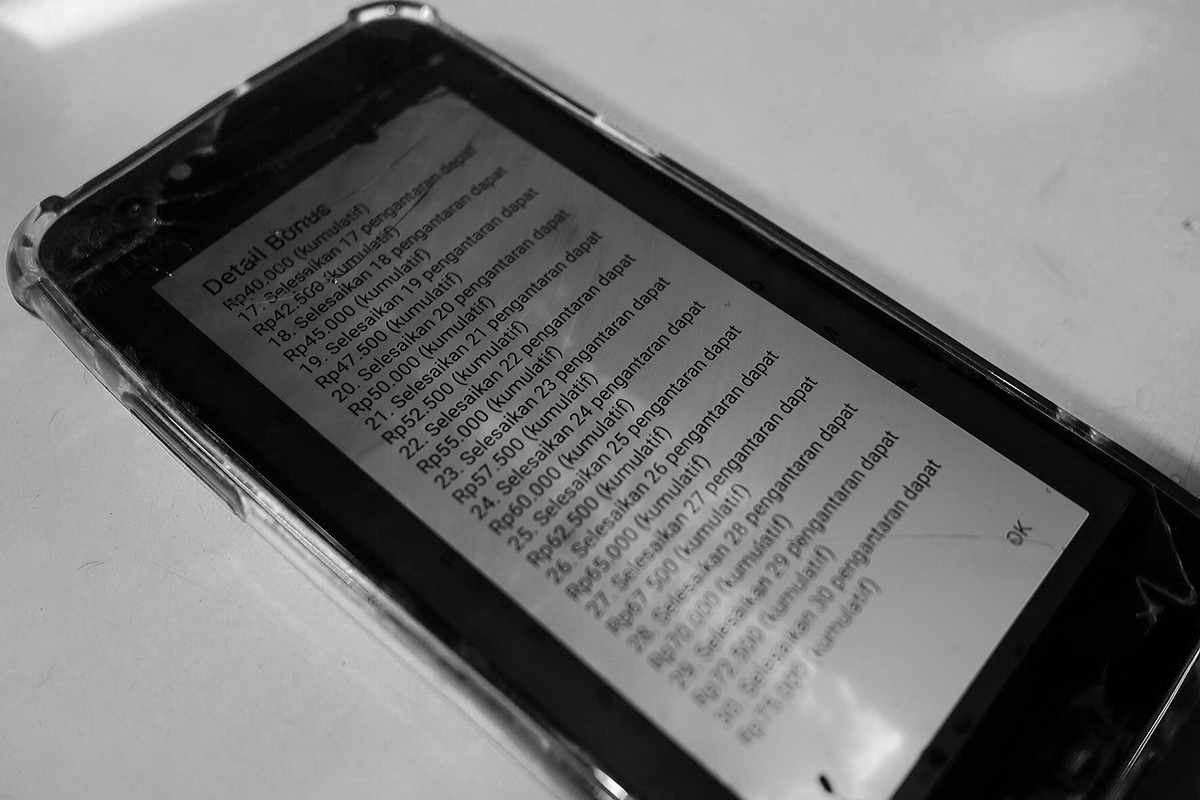

However, after the merger, GoTo cut delivery driver incentives from Rp 10,000 (69 US cents) per five deliveries to Rp 10,000 per nine deliveries. This was done with no input from the drivers, who number almost 1 million in Greater Jakarta.

Syafri and his colleagues have had to work much harder to earn the same money. The new policy hit him just as he was struggling with a high cost of living and his wife’s illness.

“My wife doesn’t know that I’m not driving now. All they know is that when I leave home, I’m driving. I come home, I bring money. The problem is, if this is the condition, what am I going to bring home?” he asked.

It was 2 p.m. Ade’s face was worn out, his long hair in tangles. Apologizing for his appearance, Ade invited me to sit down for coffee.

He took me to a modest building at the end of a road with gazebos (cakruk) where people can get a quick bite or drink and lie down. It’s where Ade and other drivers spend time after sweating it out on the streets.

“This is a kind of base where we get together. Usually guys come here after delivering their goods,” said Ade, refreshed after washing his face.

Ade’s caring leadership makes him a popular and respected member of the driver community. When something goes wrong that might harm couriers, Ade has always been on the front line fighting. The incentive cut is no exception.

For Ade, GoTo has abused the principle of partnership as stated in Indonesia’s Law on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), which prohibits large businesses from owning or controlling MSMEs.

From the onset, couriers were not involved in GoTo’s policy formulations. The company denied this, alleging that several couriers were invited to negotiations. However, Ade claims these couriers were stooges who failed to represent the interests of couriers.

“What the boys and I heard here was that those who came [to the office] only listened to the management talk,” Ade said. “No one was invited to discuss the new policy.”

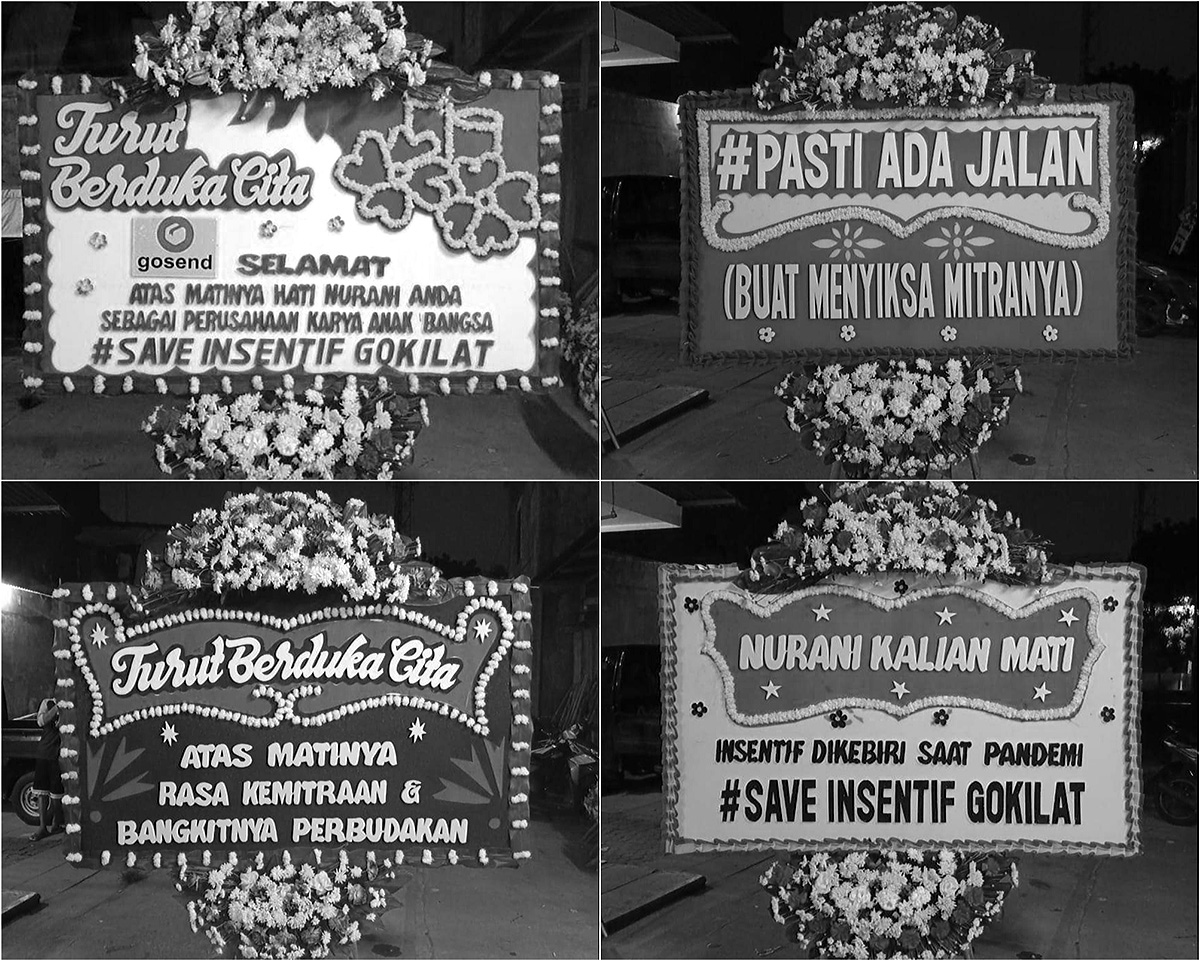

In protest, the couriers sent more than five funeral wreaths with pithy messages to GoJek’s headquarters in South Jakarta. “After my son was circumcised, how come my incentive was circumcised too?” one read. “Condolences to the death of partnership & the rise of slavery” said another. A photograph of the wreaths went viral on social media, sparking a debate on the fate of the couriers.

Couriers also went on an informal strike–called an “off bid”–for three days. While there are no exact figures on how many couriers took part, Ade estimates that the number might have been more than a thousand.

While labor actions like the off bid can indeed affect the flow of goods, Ade said the incentive cut required a serious response. The company crossed a line by ignoring the existence of the couriers.

This was not just talk to Ade. Being a courier requires patience and extra care–as well long long hours. Couriers lack leverage over the company’s systems and applications, yet they are forced to drive on.

Here is how it works, more or less. Couriers accept orders that are aggregated into groups of five different deliveries, each with different pick-up and drop-off points. Couriers accept orders without knowing the size or weight of the items that they’ll be transporting.

While a courier can opt out of delivering a package that is too big, cumbersome, or far away, they’ll have to proceed to the second delivery point to start making money–which costs the drivers time and results in lost income.

Rather than canceling, couriers take unimaginable orders under tight deadlines. Ade, for example, carried a glass panel nearly one meter high. Another courier, Hendi, had to struggle to deliver five large sacks of rice.

“It’s a hassle, bro. Carrying that much rice is hard, right? If you don’t take it, you lose. But if you have to take it, how come it’s so much trouble?” said Hendi, laughing.

Unsurprisingly the new company policy sparked protests, as the incentive cuts only added to the couriers’ burdens.

“The money that we take home is for daily necessities and other stuff. Now, if you can’t get Rp 10,000 a day, is it even worth it?” said Budi, a courier in Kebayoran Lama, South Jakarta.

Arif Novanto, a researcher at the Gadjah Mada University (UGM) Institute of Governance and Public Affairs, said that the protests on incentive cuts were to be expected. According to Arif, most couriers in Greater Jakarta were migrants, trying to build better lives for themselves and their families in the capital.

Research by University of Indonesia’s Faculty of Economics Demographic Institute stated that the Covid-19 pandemic left 63 percent of motorcycle taxi drivers without income. Almost all drivers have dependents and do not have a backup source of income.Click To TweetArif’s research said that the average gross income of online couriers fell by 67 percent in the month after the pandemic started. The government’s “new normal” policy, which featured mobility restrictions to curb the virus, did not help much either.

As a result, many partners quit because they could not pay their motorcycle loans–or just from worries over their health during the pandemic. Those who persevered increased their work hours–some pulling 24 hour shifts– to make as much money as they could while they could.

GoTo publicist Audrey Petriny denied that the company changed its revenue scheme–or the basic fare per kilometer–for drivers, and had only adjusted incentive schemes to provide greater opportunities for partners.

“This policy is a step to more evenly distribute the number of partners who can receive these incentives, so that more partners have the opportunity to earn additional income during the pandemic recovery period. GoSend also has various appreciation programs for partners with good performance,” Audrey said.

Ade disagreed. Management, he says, ignored the facts on the ground: the incentive cuts feel real and the couriers are the ones that suffer the most.

“How is this caring? Clearly the cuts exist and impact us. So we went on a mass strike,” said Ade.

The problems facing drivers are complex, and did not happen at once. Over the years, local headlines have chronicled their woes, from overly complex applications, to the levying of excess fees, to trimming bonus conditions.

One thing is clear: although GoTo calls its drivers “partners”, it’s not an equal partnership.

Nabiyla Risfa Izzati, a labor lecturer at UGM, says the problem is rooted in the DNA of the gig economy, which stimulated the growth of the Indonesian ride-sharing business after the 2008 financial crisis.

The gig economy disrupts the conventional job market and promises increased efficiency through an on-demand mechanism, e.g., an app. But who is the employer in the gig economy? The answer is confusing, says Nabiyla. “The gig economy indeed has companies, but they claim that they don’t provide jobs–that they are just intermediaries. This then does not fit in our system of employment, even though in the eyes of consumers it is the opposite, eventually creating a gray area. The logical consequence is that drivers are at a great disadvantage.”

Another labor researcher, Fatimah Fildzah Izzati of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), said that companies obfuscated the idea of ideal work with the rhetoric of entrepreneurship, freedom, and flexibility.

“[Positive] aspects seen in the digital economy are non-material, while the material ones such as decent wages tend to be ignored,” Fildzah said. “This ‘partner’ position and flexible work also make it easy for drivers to be replaced by others because the requirements to qualify are not difficult.”

The incentive cuts underscore the tendency of all employers to recruit cheap labor, said Fildzah. This process is accelerated by mergers that make companies stronger, in terms of capital and leverage. “With this merger, the partnership status has become even more blurred.”Click To TweetIndonesia’s laws have yet to catch up with the gig economy. The Law on SMSEs, for example, doesn’t explicitly cover the gig economy, which took hold in Indonesia the same year the law was enacted.

Meanwhile, Transportation Minister Regulation 12/2019, used by local superapps and drivers as a legal basis to cover their activities, only regulates the use of two-wheeled motorized vehicles carrying passengers through application companies or online motorcycle taxi intermediaries. The regulation doesn’t cover online couriers, says Transportation Ministry representative Adita Irawati.

This legal loophole has been used by the superapps to pressure partners. Online couriers have no legal reference on labor relations, such as the guidelines for calculating service fees for online motorcycle taxis are provided by the regulation.

So what is the way out? Fildzah said drivers needed collective bargaining and unions for a start. “What needs to be understood is not to make the union an end, but to make it the beginning.

Another Gojek driver, Aji, said that one night, some months ago, he ran out of gas somewhere at the edge of town between South Jakarta and Tangerang. The streets were deserted. He was overcome with fear, not of ghosts, but of begal, or street robbers.

“I was just dazed. My body was totally spent, and the motorbike just had to break down because it ran out of gas,” said Aji when I met him in Barito, a popular hangout spot in South Jakarta. “Just a total mess.”

Luckily his phone was still on. Right away he sent a message asking for help to a driver WhatsApp group. Half an hour later, two drivers, who he did not really know, came from Kebayoran with two bottles of gasoline.

“I was just relieved. Maybe it would have been different if these guys didn’t come,” he said with a smile.

These WhatsApp groups are crucial for online drivers. They are a means of communication and cultivate solidarity amid the pandemic and the company policies that make drivers’ lives so complicated. The word “solidarity” now resonates in this conversation room.

Aji’s story is just one example. Ridwan, a courier from Duren Sawit, for example, said WhatsApp groups were vital when misfortunes appeared. In March 2019, he had an accident in Sunter, North Jakarta, shortly after delivering goods. He fell as he tried to avoid road excavation work. His motorbike was badly damaged, his left arm severely sprained.

He sent one message to a WhatsApp group that was read by dozens of drivers from across the city. In less than 15 minutes, three drivers came and rushed him to the nearest hospital. A few days later, Ridwan received donations from members of the WhatsApp group.

“I didn’t see how much it was. What’s important is the solidarity that fellow drivers showed when I had the accident. That really touched me,” he said. “In fact, many of the group members don’t know each other personally … But the solidarity is incredible.”

Ade agreed that WhatsApp groups have been a popular medium among drivers. Drivers join at least one group, not only to get up-to-date information about work, but also to coordinate and show solidarity. A WhatsApp group can have over 100 drivers, depending on individual needs.

From WhatsApp groups, relationships can continue with face-to-face meetings, which has led to the emergence of even larger groups: communities. These highly diverse communities include groups organized according to their regional bases or their specific work–couriers, regular motorcycle taxi drivers, or food delivery drivers.

Several communities are spread throughout Greater Jakarta. Ade estimates there are more than 30 online courier communities in Greater Jakarta, each with dozens of members.

“And that’s just couriers. Not including drivers in other lines of work. The number is definitely higher,” he said.

This base provides a fairly strong foundation from which drivers can strive to demand real changes to improve their lives. The precedent clearly shows the effect of this factor.

In the United Kingdom, Uber drivers have closed ranks and demanded that their inherent “partner” status be changed to “employee.” Last March, their demands were granted. The UK Supreme Court ordered Uber to recognize approximately 70,000 drivers as employees along with their rights, such as minimum wage and pension funds.

In Spain, a collection of online couriers for various applications—Deliveroo, Glovo, UberEats— succeeded in demanding that the government change their status to workers. The companies are now required to manage the transition by September 2021.

The impact is clear: online couriers will be entitled to the same rights as workers in general, including sick leave and vacation benefits. In addition, the new rules also require companies to be transparent in the use of algorithms used to monitor employee performance.

Another example is an initiative in New York, in the United States. A group of former online drivers started their own transportation company, naming it The Drivers Cooperative. The goal: to return profits to drivers, not corporations; to end exploitative labor practices; and to create a more democratic business management climate.

The founding of The Drivers Cooperative was motivated by the drivers’ high vulnerability, the majority being immigrants. Additionally, 40 percent of their income was taken by the company. The Cooperative’s emergence can also be seen as a criticism against the corporate perspective that sees drivers as partners, thus eliminating the obligation to pay wages according to the law and fulfill other rights.

According to Ade, the popular GoJek drivers’ leader in the neighborhood, it is not that there is no desire to organize or unionize. Several times the idea had been floated to strengthen the couriers’ position with respect to the company, and before the law. However, there are innumerable obstacles, including a lack of collective awareness of being marginalized.

“Quite a few think that being a courier is not that burdensome. Others think the most important thing is to make money first,” Ade said.

However, when the company changed its policy, the dynamics changed immediately. The recent courier mass strike was followed by the broadly hailed Online Courier Work Union (Sejaring). Despite the lack of experience, like that of factory workers, this move is something to be supported.

“What’s important now is to ensure that this union can continue to exist among drivers, the government and the company,” said Arif. “Because with the union their bargaining position can be strengthened even more.”

The union establishment, Nabiyla says, can also be read as a way to raise class awareness and underscore the urgency of issues that determine the fate of couriers. The road ahead is long, she added, as it will have to cut through the red tape if the union is to be officially recognized.

“It’s no less difficult to convince people that this online courier union is a union just like any other. The government should not turn a blind eye to the common condition that many believe that there is no ‘working relationship’ between couriers and platform companies. “We need to have an open mind,” she said.

The merger of Gojek and Tokopedia is celebrated by many, as seen by the many memes and formal remarks by officials and members of the elite. Many hail it as a new era for the digital economy. Their ambitions are big: with an estimated valuation of Rp 570 trillion, they hope to contribute to advancing the domestic economy through their various plans, including an upcoming initial public offering.

Those at the top talk about the potential of the digital economy and dream of a competitive Indonesia. Meanwhile couriers continue to be bullied by exploitative policies.

“Imagine, Bang, even at the outset, this is what we have to experience,” says Ade. “They’ve just merged and they bear the slogan ‘A creation of the nation’s children.’ How can they treat couriers like this?”

Editors: Mawa Kresna, Ati Nurbaiti, Christian Razukas

The translation of this article from Indonesian to English is made possible through the generosity of one of our readers, Miki Salman.

This article was first published in Indonesian as part of the series “Little Cogs in the Big Tech Machines.”