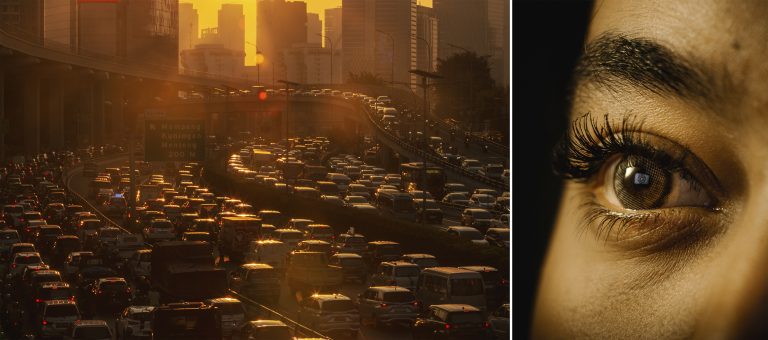

Workers in nickel industrial park in Morowali and North Morowali grapple with the grim realities of death, suicides, accidents, asphyxiation, contract violations, and wage reductions. The workers’ protests and grievances are met with imprisonment as the current Indonesian government continues to promote the nickel industry.

As she stared at her second child, Mulyati could not hold back her tears. Her son Jumardin, a 23-year-old now incarcerated behind bars, remained in a separate room from Mulyati. This visit denied the mother and son the simple act of physical touch, forcing them to raise their voices.

On that particular day, the North Morowali Police’s office experienced a power outage. The police could not print and issue any visiting permit. A police officer informed Mulyati, “Please wait, Ma’am. The power hasn’t been restored yet.”

The local time was approaching 10 am, and Mulyati feared that waiting longer might mean losing her opportunity to visit Jumardin. As the day progressed, the queue tended to grow longer.

Inside the holding cell, Umar, as Jumardin is affectionately known, gripped the bars. His gaze was fixed on his 40-year-old mother, who was shedding tears in silence.

“Please don’t let me spend the Ramadan here,” Umar pleaded. His voice filled with desperation.

Ramadan, known as the fasting month in Indonesia, is when Muslims usually gather with their family. But Umar eventually would remain inside the cell, unable to come home for suhoor or breaking of the fast.

Mulyati explained that the journey from her home to the police station typically takes about 30 minutes. She usually relies on a motorcycle borrowed from the village chief, driven by Umar’s younger sister. However, that day, the motorcycle suffered a flat tire, and they had to scramble to find an alternative mode of transportation.

Mulyati brought along some food for Umar and his fellow detainees. Umar often asked her for rice since the provisions in the detention cell were meager, and the dishes were lacking. “He mentioned that the food there barely–,” Mulyati didn’t finish her words. “He always requests for more rice. Just plain rice!”

Exactly 12 minutes after Jumardin’s name was called, a police officer approached Mulyati and told her that the visitation time had come to an end.

“Let’s hope we can secure your release before the start of the fasting month. Make the request, plead your case; you never know, they might grant it,” Mulyati encouraged, and Umar nodded.

Mulyati, 40 years old, shows a photo of Jumardin, her second child who is the backbone of the family. Jumardin worked in the smelter division of PT GNI, North Morowali, Central Sulawesi. Jumardin was one of the workers who were arrested and detained by the Indonesian Police following a strike that led to clashes between Indonesian and Chinese workers on January 14, 2023. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

JUMARDIN – Caught in the Wrong Place, at the Wrong Time

On the fateful night of January 14, 2023, Jumardin bid farewell to his family as he headed for the night shift at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry. Little did the family know it would be the last time they saw him at home.

Typically, Umar would return home by 9 am the following morning, or at the very least, he’d notify his family if he intended to stay out overnight. However, by 11 am the next day, there was no word from Umar.

Mulyati, his mother, grew increasingly anxious. She requested Umar’s sister to contact him, but they received no response. As noon approached, a family member arrived at their doorstep with heart-wrenching news – Umar, the breadwinner of their household, was detained at the local police station. The shock left Mulyati unconscious.

Born in 2000, Umar was the only one among four siblings to graduate from vocational school. His family hailed him as the most dedicated and intelligent of the lot, pinning their hopes on his future.

The family resides in Onepute Village, West Petasia, North Morowali, Central Sulawesi. Umar’s 60-year-old father is plagued by old-age illness. He used to operate a motorcycle taxi, shuttling back and forth to Kolonodale, the hub of North Morowali government, some 13 kilometers from home. His health deteriorated, particularly his back.

Umar assumed his father’s responsibilities. After completing his vocational education, he supported his parents, three siblings, and a nephew by taking odd jobs.

Three years later, Umar learned of job openings at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry. Many young people from his village applied, and Umar was among the chosen few in the smelter division. He earned a monthly wage of Rp3,150,000 (USD 200) – which is the minimum wage in North Morowali regency – coupled with meal allowances and overtime pay. In a region marked with poverty and a high unemployment rate, Umar’s wage meant a lot – it was well above the provincial minimum wage in Central Sulawesi at Rp2,390,000 (around USD 150).

Unlike Indonesia’s capital city DKI Jakarta, North Morowali is considered a much more underdeveloped region. More than 12% of Central Sulawesi’s population lives in poverty. According to Central Bureau Statistics, about 75% of the population is barely able to fulfill their basic food needs, falling under the food poverty line.

PT GNI began constructing its smelters in 2019. The company is part of Indonesia’s National Strategic Project (PSN) and is the biggest nickel processing industry in North Morowali. With a total investment of 3 million USD (around Rp 40 billion) from a Chinese company Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry, PT GNI is considered to be the second biggest industrial park in Central Sulawesi, after its predecessor Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) in Morowali.

As Umar remains behind bars with no income, the family now grapples with meeting their daily expenses. Occasionally, kind-hearted neighbors extend their support by sending over food. Sometimes, Mulyati takes on laundry and cooking tasks for other households, earning Rp20,000-25,000 (around USD 1.5) for her services.

Upon taking the smelter job, Umar also took on credits for a motorcycle and mobile phone that he used for work. Since he was detained, he could not pay the installments – totaling at Rp2.7 million (around USD 170) per month.

In April, the family reached a dead end, unable to pay the debts. While the motorcycle installment could potentially be transferred to another party, returning the phone posed a conundrum. Umar’s mobile phone remains in police custody, deemed as “evidence.” Meanwhile, the service provider continues to bill Umar’s family, demanding prompt payment or the return of the phone.

Yulan, Umar’s elder sister, made efforts to communicate with the investigators. “The investigator assured us that the mobile phone would be returned, but he mentioned the presence of data that still needed analysis,” she said. “If there’s specific data you require, take it, but please return the phone.”

Umar’s family regularly visited the North Morowali police station, where the detained nickel smelter workers were held. The family is of Bugis descent, indigenous to South Sulawesi. But they have settled in North Morowali for generations, becoming proficient in Mori, the native language of the indigenous Mori tribe in the region. Umar and his family consider themselves more of Mori than Bugis.

In stark contrast, other detainees were predominantly migrants, originating from South Sulawesi, hailing from Palopo, Pinrang, to Makassar. It was much harder for their families to visit, as the journey meant an additional financial burden and demanded extra time and effort.

Mulyati and her daughter once brought Bilal, Yulan’s 5-year-old son, to visit. Umar loves playing with his nephew, even late at night after he finishes his shift. Bilal missed his uncle, constantly inquiring when he’d be home.

“When Bilal came, Umar refused to see him. Umar pleaded so that Bilal was brought home. He could not bear the thought of being seen by Bilal in his current condition,” said Yulan. “Meanwhile, Bilal had missed his uncle for so long since Umar never came home.”

“I myself… I couldn’t visit Umar, my heart… it still aches,” Yulan lamented.

Bilal sat beside his mother, just back from his Quran recitation.

“Where’s Uncle?”

“In prison.”

THE DAYS that Umar spent in a police detention cell were fraught with uncertainty for his family. They anxiously awaited answers to some pressing questions. How much longer would their son be detained in the police station? When would Umar return home, and under what circumstances?

Initially, the family was informed that Umar’s detention would last only 1 to 2 days. “We were told that it was for his own safety,” Mulyati recounted.

However, after two nights had passed, news arrived from Jakarta. National Police Chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo announced 17 individuals as suspects, with Umar among them. That very night, the detained workers were transferred to detention cells within the confines of the North Morowali police station.

Didik Supranoto, the Head of Public Relations for Central Sulawesi Regional Police, explained that investigators had charged 16 suspects with accusations of mobbing, with a potential 5-year prison term. One worker faced an even more severe charge of arson, which could lead to a 12-year prison sentence.

However, Umar’s family remained in the dark, oblivious to these developments. When Project Multatuli met them in March 2023, their sole concern revolved around Umar’s release date.

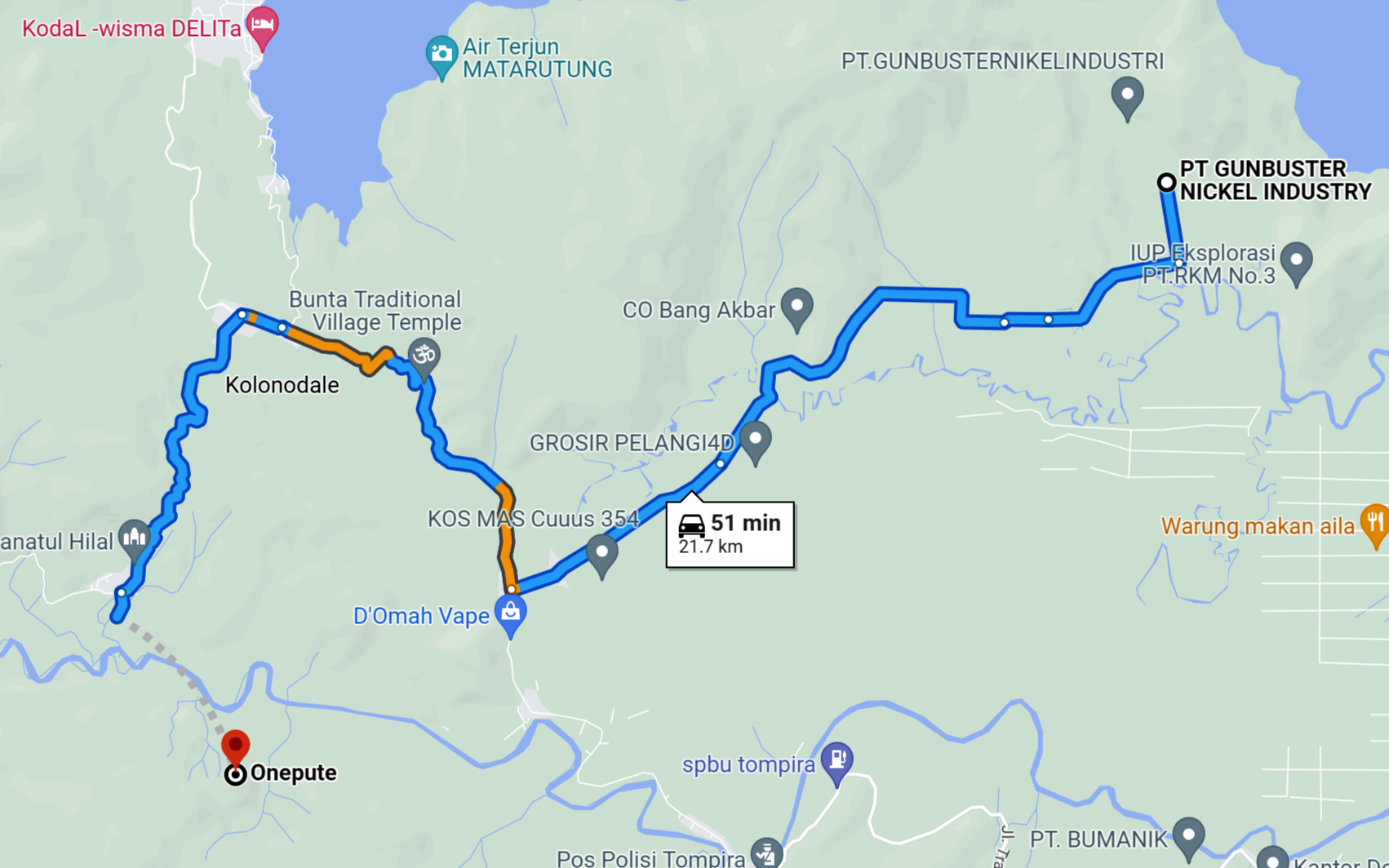

Umar rarely complained about work. He seldom divulged the challenges he encountered while on the job to his family. Before owning a motorcycle, Umar relied on fellow workers for rides to and from PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI). The journey from Onepute Village to the GNI area spanned approximately 27 kilometers, requiring an hour of travel.

“At times, when there was no ride available, he’d find himself stranded,” Yulan narrated. “That’s when his father suggested, ‘You should buy a motorcycle. You’re an adult now, take matters into your own hands.'”

Umar rarely told his family about the working conditions within the smelter section. Once he talked about it, he described it as unsafe. There was no necessary personal protective equipment. On his first day at work, Umar was equipped with nothing more than a helmet. It took several months until he finally received a pair of safety shoes.

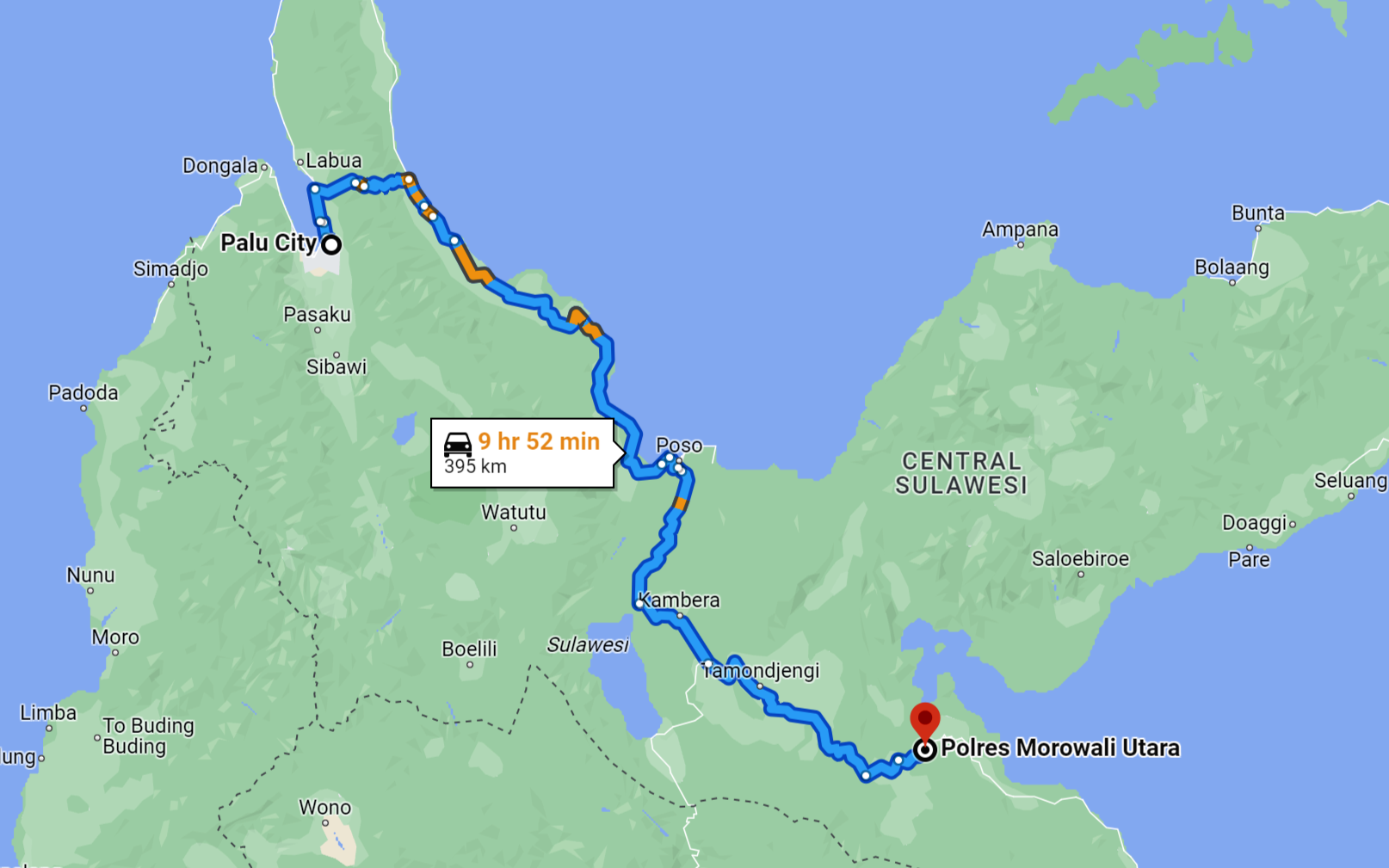

The distance Jumardin travels to go to work every day. (Google Maps)

THE STRIKE – How the Company is Pitting Domestic and Foreign Workers Against Each Other

The workers at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry commonly referred to the main gate as “Post IV.” It was here, in front of this gate, that the National Workers Union (SPN) staged a strike that persisted until 5 pm on January 14, a day fraught with tension and uncertainty.

This strike did not only involve union members; it attracted non-union workers as well. Even after the official dispersal of the strike, a group of night-shift workers continued their protest well into the night.

The National Workers Union (SPN) presented a list of eight demands:

- The company is obligated to implement K3 procedures in line with existing laws.

- The company is required to provide complete Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to workers according to the specific risks associated with their roles.

- The immediate formulation of company regulations.

- Stop wage reductions without clear justification.

- An end to fixed-term employment agreement (PKWT) for permanent positions.

- The rehiring of employees (SPN members) who had their contracts terminated during previous strikes.

- The installation of air circulation systems in warehouses and smelters to mitigate dust exposure.

- The company should clarify the fulfillment of rights that the families of deceased workers I Made Defri Hari Jonathan and Nirwana Selle deserve in accordance with norms and regulations.

The eighth demand is related to the tragic incident involving workers named I Made Defri Hari Jonathan and Nirwana Selle. In late December 2022, they were trapped in a hoist crane during an explosion of one of the smelter furnaces. Tragically, Nirwana Selle was live-streaming on TikTok when the accident occurred, and the video quickly went viral on social media.

Amirullah, the Chairman of SPN at PT GNI, noted that labor protests had escalated significantly following the deaths of these two workers. The strike on January 14 was part of a series of labor protests that had been ongoing since 2022, predominantly driven by workers from the smelter and dump truck divisions. Their primary objective was to demand improvements in working conditions and wages. These protests were occasionally organized by SPN and sometimes spontaneously initiated by fellow workers.

Following the death of Nirwana, Amirullah recalled, “Fellow workers began to ask when SPN would strike.”

During the protest, Minggu Bulu, an SPN official at PT GNI and the coordinator of the strike, emphasized the importance of their demands in his speech. “We work with safety as a top priority. It’s not just about work,” he urged. Minggu Bulu was a former dump truck driver, but remained involved in the union even after he was fired for his activity at SPN.

After the strike concluded, one worker informed SPN officials that two of his friends had been taken into custody at the North Morowali police station. In response, they prepared to visit the police station, awaiting a break in the rain. They arrived at the station around 8 pm.

By 11 pm, they had left the police station and returned to their homes. However, as Amirullah reported, “I received information about disturbances within the PT GNI area.”

Minggu Bulu couldn’t provide details about the incident within the industrial area as he was in front of Post IV, coordinating the strike. But he heard accounts of the increasingly hostile situation inside.

On that fateful day, Jumardin hesitated to work. His mother was aware of the strike and advised her son not to report for the night shift. However, around 10 pm, Umar’s coworkers contacted him, reporting an unsettling rumor about Chinese workers assaulting Indonesian workers who were participating in the strike. They urged Umar to remain on duty, as he held the position of deputy superintendent in his division and the chief superintendent was on leave. His presence was essential.

“Why are you at home? You’re the deputy supervisor,” Yulan emphasized, recounting what Umar’s coworker said.

Umar arrived at PT GNI at 10 pm. Upon reaching Post IV, he was denied entry on his motorcycle, and he left the vehicle parked outside. “The motorcycle was left on the road without being locked properly,” Yulan said.

The clash erupted at 11 pm. By 1 am, Umar had left Post IV but was apprehended by the police, alongside 71 other workers. Alternative sources indicated that more than 80 workers were arrested.

When questioned by investigators, Umar stated that he had only thrown stones at the Chinese workers. “Just once or twice,” Yulan noted. “He was reserved and shy. He’d only speak when spoken to and was otherwise withdrawn.”

A video circulating online depicted a group of workers within the industrial park, shouting slogans like “Basmikan Cina. Basmikan Cina!” (Kill the Chinese). This racially charged anger seemed to be triggered by an earlier attack by Chinese workers when Indonesian workers were on strike. The Chinese workers were reportedly armed with iron pipes, which they used to assault their Indonesian counterparts. The violence escalated to include vandalism and vehicle burning, prompting retaliatory stone-throwing before security forces intervened.

According to a January 18 report by China Labor Watch, PT GNI’s management had deployed Chinese workers to quell the strike, barricading factory buildings and safeguarding company assets. The New York-based organization, dedicated to monitoring Chinese labor practices, noted that rather than de-escalating the situation, PT GNI inadvertently pitted Chinese workers against their Indonesian counterparts, creating an “us vs. them” narrative. Many Chinese workers feared becoming targets of anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia. Some were even stationed at the frontline, equipped with helmets and iron pipes provided by management to defend themselves and, ultimately, the company.

A worker wears a safety helmet. Work safety is a major concern for both the Indonesian and Chinese workers at PT GNI. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

Additionally, due to language barriers, Chinese workers initially struggled to comprehend the demands of the strike. Later conversations with Chinese workers at PT GNI and China Labor Watch revealed that they eventually acknowledged that these demands were relevant to their working conditions as well, especially concerning safety.

Initially, many Chinese workers thought the protests were solely related to wage increases among Indonesian workers.

Chinese workers also shared an interest in supporting the protests. China Labor Watch reported that many Chinese workers had fallen victim to various malpractices by PT GNI, including delayed salary, arbitrary wage cuts, non-transparent recruitment, extended overtime, physical abuse, sexual harassment, passport confiscation, and restrictions on the mobility of Chinese workers.

The clashes on that Saturday night reportedly resulted in the deaths of two individuals, one Indonesian worker and one Chinese worker. However, apart from the police’s statements, few details regarding the cause of these deaths are available. Sr. Comr. Didik Supranoto, then-spokesperson for the Central Sulawesi Police, initially said that there were three deaths: two Indonesian workers and one Chinese worker. The identities of the deceased remain unknown by the SPN. The union has demanded the police to disclose the details, but has yet to receive a response.

After the clash, the demands of the workers faded into the background. In the media, the prevailing narrative revolved around the racially-tinged “horizontal conflict” between Indonesian and Chinese workers.

MINGGU BULU – Worker Caught in the Crossfire

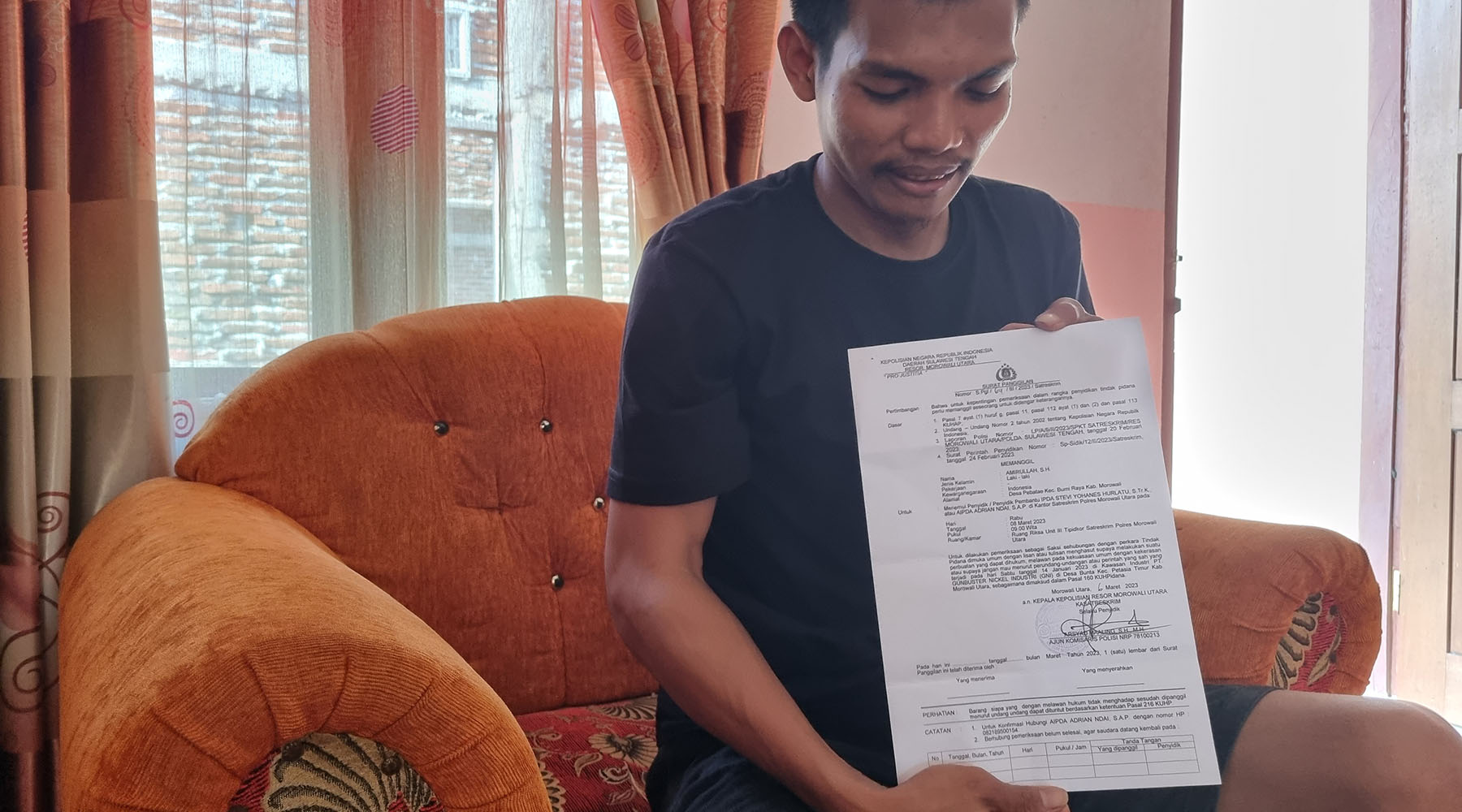

Ever since the clash between Indonesian and Chinese workers and the subsequent detention of numerous laborers, Minggu Bulu’s nights have been restless. He has found himself in the crosshairs of the law. Initially summoned as a witness, he was later designated a suspect in April 2023, alongside Amirullah, charged for inciting a riot with a threat of 5-6 years in prison.

According to Hasbi from the People’s Legal Aid Coalition, the worker’s attorney, it appears that the Indonesian police aim to blame the union strike for the clash in the evening.

Amirullah, the Chairman of SPN at PT GNI, shows the letter summoning him as a witness by the police. The police named him as a suspect in April 2023 under the article of sedition. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

Minggu Bulu, at 33 years old, has to take care of his wife and four children. After two years of unemployment due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Minggu Bulu, who comes from Toraja in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, sought employment as a dump truck driver at PT GNI. The journey from his village to the company covers a daunting 270 kilometers. He chose to relocate to North Morowali due to a dearth of job opportunities in his hometown, where farming was the predominant occupation for his parents’ generation.

Initially, Minggu Bulu believed that securing a monthly income at PT GNI would provide his family with financial stability. However, after working for PT GNI for 20 months, he saw the job as a precarious and arduous undertaking.

The workers’ WhatsApp groups often received information about the death of a worker or workplace accidents. In March, a Chinese worker tragically fell from a considerable height. An Indonesian worker lost his life when he became entangled in a conveyor. Reports emerged of collisions in the work area, with two dump trucks accidentally colliding, crushing one driver’s knee. Another incident involved motorcyclists being struck and crushed by a tipping truck. While some survived, others were not as lucky.

“There was one day when we had three accidents,” Minggu Bulu recalled. Nevertheless, the company management seldom provided transparency to workers regarding such incidents. Instead, workers were occasionally held responsible or accused of negligence.

Minggu Bulu himself has experienced such an episode. On a typical workday, he was operating a dump truck when he inadvertently struck a motorcycle parked directly behind the truck. “I backed up and hit it, damaging the bike.”

In response, Minggu Bulu went to the company’s safety department for help. However, he was directed to the Human Resources Department and was then instructed to pay for half of the motorcycle’s value as compensation. The Human Resources Department argued that both parties bore responsibility: the motorcycle owner parked his bike at the wrong place and Minggu Bulu was blamed for causing the accident.

Minggu Bulu was puzzled by the decision. “If it’s a 50:50 split, does it imply shared liability? How about the company’s responsibility? According to the rules, two-wheeled vehicles should not be in the area.”

Despite his resentment, Minggu Bulu paid for the compensation out of his own pocket. Fortunately, there were no casualties at that time.

In Minggu Bulu’s view, working at PT GNI entails not only the risk of workplace accidents but also the challenge of dealing with capricious superiors and inconsistent company regulations. Ultimately, he lost his job for his role in the National Workers Union in late 2022. He wanted to return to his parents’ farm, so he could enjoy freedom, free from oversight.

However, what happened on January 14 changed the trajectory of his life. He is now waiting for the state to decide his fate.

His movements were closely monitored even when he was still considered a witness. Police visited his boarding house in the Tompira area of East Petasia. While attending a discussion with various trade unions in Palu, the capital of Central Sulawesi, three policemen apprehended him and escorted him back to North Morowali on an arduous 8-hour journey.

During a visit to Jakarta for a meeting between the National Workers Union and PT GNI, mediated by Deputy Minister of Manpower Afriansyah Noor, two North Morowali policemen approached Minggu Bulu, embraced him by the shoulders, and handed him a second summon.

The experience took a toll on his mental well-being. “When they delivered the letter in Jakarta, I was bewildered. I was just a witness; why did the police chase me all the way to Jakarta?” Minggu Bulu wondered.

A rented house near PT GNI. The rent price for houses ranges from Rp 1.5-2 million per month. Workers usually rent a house together with one or two other workers to reduce the cost. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

UNION SUPPRESSION – Newly Enacted Law Makes Work More Precarious

The entrance to PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (PT GNI) presents a snapshot of a crowded workday. In the late afternoon, around 5 pm, workers on motorcycles crisscrossed the area as shift changes unfolded.

Some workers paused briefly at the roadside stalls just outside the industrial zone, where a repair shop attended to a queue of motorcycles in need of washing or repair. A few wore yellow helmets along with the grayish PT GNI uniform shirts, while others sported various outfits, including uniforms from different companies. The diversity of attire spoke to the varied roles and backgrounds of the workers. Some were clad in pants that matched their PT GNI shirts, while others opted for jeans or trousers.

Uniform stores lined the vicinity, offering the tops sans pants for a fixed price of Rp 200,000 (around USD 13). Interestingly, these uniforms were sourced directly from PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), another nickel industrial hub located 164 kilometers from PT GNI, along the coast of Central Sulawesi. According to one vendor, these garments were the most affordable option. “For the top only,” she noted. “If you prefer wearing jeans, that works too.” The seller also offered helmets from IMIP, praising their durability over the default helmets provided by PT GNI. “An IMIP helmet costs IDR 300,000 (around USD 20), brand new.”

A shop sells work uniforms on the road to Post IV, the entrance gate to PT GNI. The seller supplies personal protective equipment (PPE) from various smelter industrial companies in the Morowali and North Morowali area, including PT IMIP. (Project M/Permata Adinda)

Amid this industrial hustle and bustle, we met Hikmah, a worker at PT GNI, who had recently returned from his shift and agreed to meet us later for a conversation. By 7 pm, he had made his way to a coffee shop in Bunta Village, taking a short break before heading back to his boarding house in Kolonodale. Hikmah was joined by a young man in his twenties.

“This is my neighbor. He’s looking for work, so I’ve been mentoring him,” explained Hikmah, who works as a tipping truck driver and has asked for a pseudonym. This unofficial mentoring practice, he noted, was commonplace at PT GNI.

Hikmah stressed the need for mental preparedness.

Hikmah wasn’t feeling well during our meeting, often coughing. He was considering obtaining a work absence permit to visit a health clinic, as throat and respiratory ailments frequently afflict workers. “Perhaps it’s due to the dust,” he mused, “especially for someone like me who’s exposed to coal.”

Within the area, nickel smelters spew air pollution and thick dust, limiting visibility to a mere three meters. The situation worsens during the dry season, which usually comes in April and lasts to October, marked by oppressive heat. Conversely, the rainy season blankets the roads in mud and flooding. The proximity of motor vehicles to cargo transport vehicles like dump trucks means that workers are directly exposed to road dust.

The medical mask that Hikmah wore during our meeting was the same one he used at work, a mask he had purchased himself. The company no longer regularly supplied masks to its workers. “It used to be provided, but it hasn’t been provided for about four months,” he said.

Hikmah considered himself fortunate in terms of his job, working as a truck driver in an air-conditioned vehicle. In contrast, workers in the smelter and warehouse divisions are directly exposed to ore dust. “The ore dust can be suffocating; it dries out your throat. It’s perpetually hot,” he shared. “The searing hot nickel fills the air with dust. That’s what we breathe. It even gets in our eyes, every single day.”

Hikmah frequently hears grievances from workers in the smelter division who don’t receive specialized masks for their work. The dust in their workspace is so dense that it obscures their visibility.

“Employees in the smelter wear standard masks. There used to be some colleagues wearing full-face masks, but I’ve noticed more people without them,” he said. “Within the ore warehouse, people labor in an enclosed space, completely enveloped in dust, alongside heavy machinery, and they become virtually invisible. There used to be no ventilation at all, but thankfully it exists now.”

Hikmah’s working hours span from 6 am to 6 pm, with a one-hour break. His basic monthly salary stands at Rp 3.4 million for an eight-hour workday. Overtime is compulsory for three hours each day for his division. Consequently, monthly wages fluctuate, averaging around Rp 7 million, but can increase up to Rp 8 million with additional overtime hours.

Hikmah budgets his income to pay various expenses: Rp 1.5 million for house rent, Rp 1 million for motorcycle credit, Rp 2 million for food, and the rest he sends home to support his parents and younger siblings’ education. However, not every worker receives as much salary as Hikmah does due to limited overtime. In the smelter production division, the basic salary hovers around Rp 3.4 million. Workers in the smelter and warehouse divisions often voice complaints about the discrepancy between their wages and the hardship and risks of their jobs.

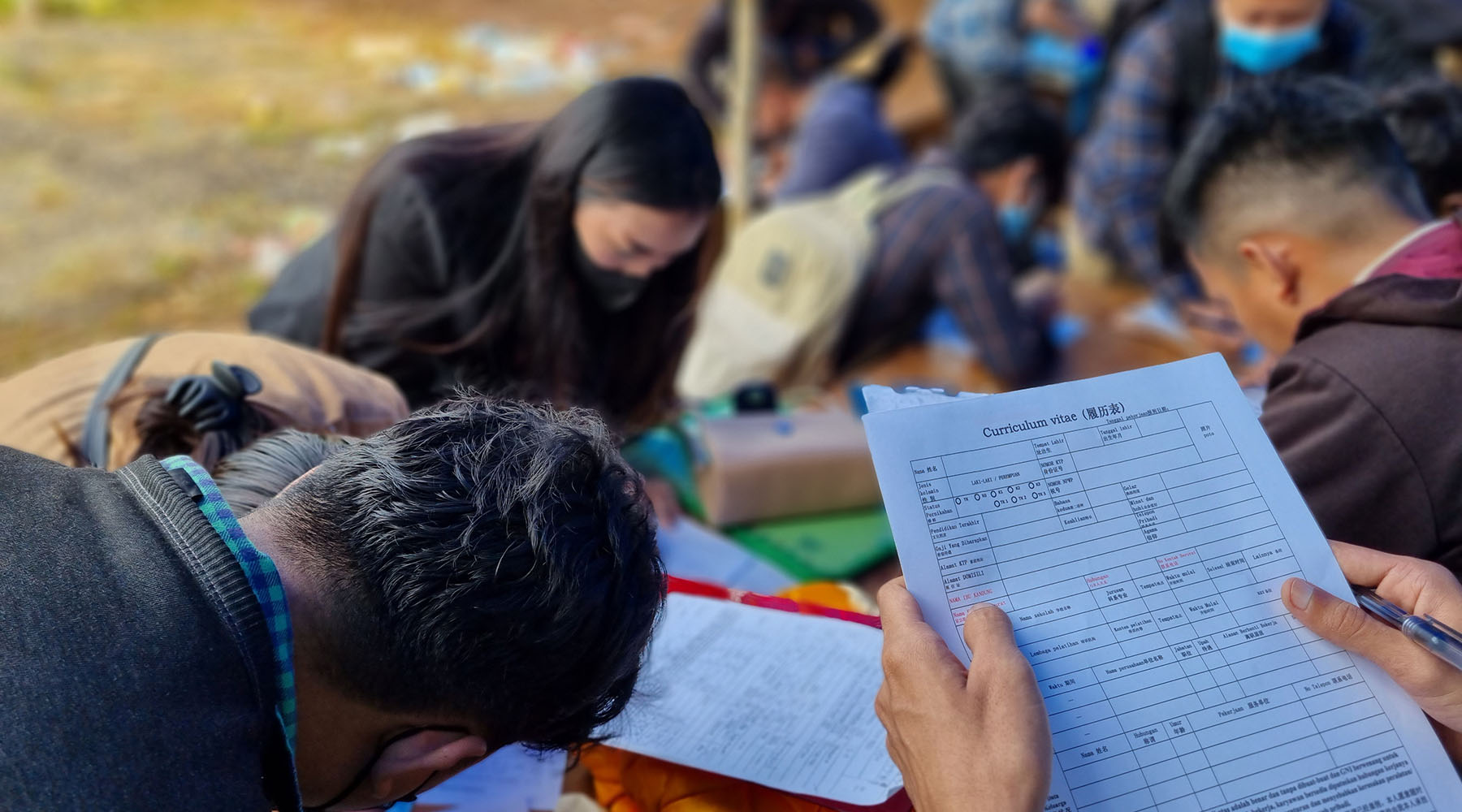

Job applicants fill out PT GNI employment forms at a recruitment event that took place in the Bungintimbe Village Office Hall, East Petasia, North Morowali. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

Even with his relatively high wage, Hikmah felt a profound disappointment with his employment at PT GNI. He began to feel disappointed early on, when there was a lack of orientation about company regulations and workplace safety. There was no essential guidance for the workers.

“It’s crucial to get to know the environment, as the industrial area itself is rife with dangers. In my previous work experiences, companies helped us get used to and adjust to the workplace,” he said.

Hikmah received work uniforms and safety equipment from the company only after two years of employment, specifically following a protest by the National Workers Union. “Initially, when I started working, I was just provided a helmet and a t-shirt like this,” he said, pointing to an undershirt behind his PT GNI uniform. During that period, he did not receive safety boots either. “I even saw some workers wearing slippers.”

While the company did offer work shoes, the quality fell short of safety standards. “They were boots, but made of synthetic leather. A friend tested them out running a truck on the shoes, and they got bent out of shape,” he said. To mitigate potential harm, Hikmah took it upon himself to purchase his own boots, deeming them safer. “These have metal tips,” he noted, gesturing to the boots he was wearing.

On January 14, Hikmah joined a strike with the National Workers Union (SPN). One of the workers’ demands was that the company cease making arbitrary wage cuts. However, after participating in the protest, Hikmah faced disciplinary action, resulting in a pay cut. The company cited his absence from work as the reason.

Hikmah wasn’t the only participant who received warning letters and pay cuts. Some workers were even terminated.

The company has also reduced workers’ benefits following that strike. Typically, aside from the basic salary, workers receive extra compensation and overtime pay, often dependent on their performance, ranging from Rp 400,000 to Rp 600,000 per month. In Hikmah’s case, a month’s worth of overtime pay was deducted from his take-home pay.

Hikmah clarified that he wasn’t an official member of the union and referred to himself as a “sympathizer” of the National Workers Union. He remarked that many PT GNI workers were interested in joining the union but harbored fears of breaching their employment contracts.

“Our only aim is to put food on the table, and it’s challenging,” Hikmah lamented.

Amirullah, the Chairman of SPN PT GNI, disclosed that union officials had disseminated 4,000 member registration forms, with the number of PT GNI workers reaching approximately 9,000 in 2022 and growing to 11,000 in 2023. Nevertheless, only a limited number of workers joined the union due to intimidation by the company.

“There’s significant interest, but the fear of repercussions from the company makes our colleagues hesitant to submit the registration forms,” Amirullah pointed out.

Puji Santoso from the SPN Central Leadership Council in Jakarta echoed this statement. Conversely, workers were pinning their hopes on SPN as the only union in PT GNI.

“They need some sort of assurance that they can keep their jobs when they join the union,” Puji remarked.

SPN was formally established at PT GNI on April 21, 2022. The union was registered with the Manpower and Transmigration Office of North Morowali Regency on May 23. However, the company initiated a clampdown after the leadership was made aware of the union’s inception.

Union officials had their employment contracts terminated one by one. Initially, this affected three managers, including Amirullah, as of July 2022. The next wave of dismissals affected Minggu Bulu. In total, ten PT GNI union officials lost their jobs, including two whose contracts were terminated following the January 14 strike.

The methods used for these dismissals varied. PT GNI’s management terminated the majority of employment contracts, but some officials were forced to resign.

The National Workers Union (SPN) Local Council Secretariat Office in Morowali. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

After the passing of the Job Creation Law under the Joko Widodo administration, companies have the authority to hire workers with contracts spanning less than a year. Most PT GNI workers initially received three-month contracts, which could be extended for six and then nine months.

However, there were instances where workers had their contract durations shortened, including Amirullah. Initially contracted for six months, his contract was curtailed to three months after the company became aware of his activity in the union. Subsequently, it was further reduced to just one month and then he was not renewed at all.

The same thing happened to Minggu Bulu. Initially, his contract was for two months, referred to by the company as a probation period. Then, it was extended to six months, and then nine months. When the company discovered that Minggu Bulu was a union official, the next extension was limited to three months. Following this, his employment was terminated by PT GNI’s management.

Minggu Bulu once sought an explanation from human resources regarding the reason for the contract termination, as there was no problem with his performance and attendance record. However, human resources directed him to his division’s leader, creating a bureaucratic back-and-forth.

In the aftermath of the strike, several union members and officials faced disciplinary actions. Minggu Bulu lodged complaints with human resources, viewing the measures as violations of the law, given that strikes were not illegal. However, all of his friends who he advocated for ended up having their contracts terminated.

“HR insists that it does not oppose the strike, but focuses on the workers’ absence. I debated against this point, it’s obvious that strike means absence,” said Minggu Bulu.

The crux of the issue, as highlighted by Puji Santoso from DPP SPN, is the contract labor system at PT GNI. The system enables companies to terminate workers’ contracts without having to provide a specific rationale, shielding them from accusations of violating labor laws.

“Companies wield the power of contract terminations with such contracts. It’s challenging for us to contest this,” Puji noted. “What needs to change is the system. Only then will workers enjoy genuine job security.”

SERVING AS AN OFFICIAL in PT GNI’s only trade union presents its own set of challenges, which have become even more daunting following the so-called clash that erupted on January 14.

Minggu Bulu, now the sole SPN official at PT GNI who still resides in North Morowali, is facing an uphill battle. His employment contract has been terminated by the company’s management, a fate that befell several other officials who either returned home or sought safety elsewhere, while some secured employment in other places.

Minggu Bulu commutes to a day job at Baoshuo Taman Industry Investment Group (BTIIG) in Topogaro, which is situated 60 kilometers or a 1.5-hour motorbike ride from his residence in Tompira Village. Meanwhile, he also has to come to the police station to answer summons as well as visit the workers who have been designated as suspects.

Managing this burden alone is overwhelming for him. “I handled most aspects, from the time they were arrested to their legal processing. It involved everything, from locating family contacts to providing support and motivation,” he noted. “But, when I became a target, I found myself perplexed. How could I offer support to my colleagues when I was struggling myself?”

Families of the suspects have been reaching out to Minggu Bulu for updates on the legal proceedings for their loved ones. “Truth be told, I’m at a loss when it comes to responding to their inquiries.”

Minggu Bulu suggested that such inquiries should be directed to legal counsel. However, the logistical challenges were twofold. Access to the North Morowali Police Station was inconvenient. The workers’ legal representatives hail from Palu, the administrative hub of Central Sulawesi, a distance of 400 kilometers from North Morowali. This required a one-hour flight to Morowali from Palu, followed by a 1.5-hour drive by car or motorbike to reach the police station. An alternative route was a 10-hour land journey. Consequently, legal teams could not always be available to accompany and visit the detained workers.

“After transferring family contacts to a lawyer, I found myself powerless. How could I offer support when I needed it myself?” Minggu Bulu asked.

The distance that the attorney of the workers have to go through from Palu to the North Morowali Police Station. (Google Maps)

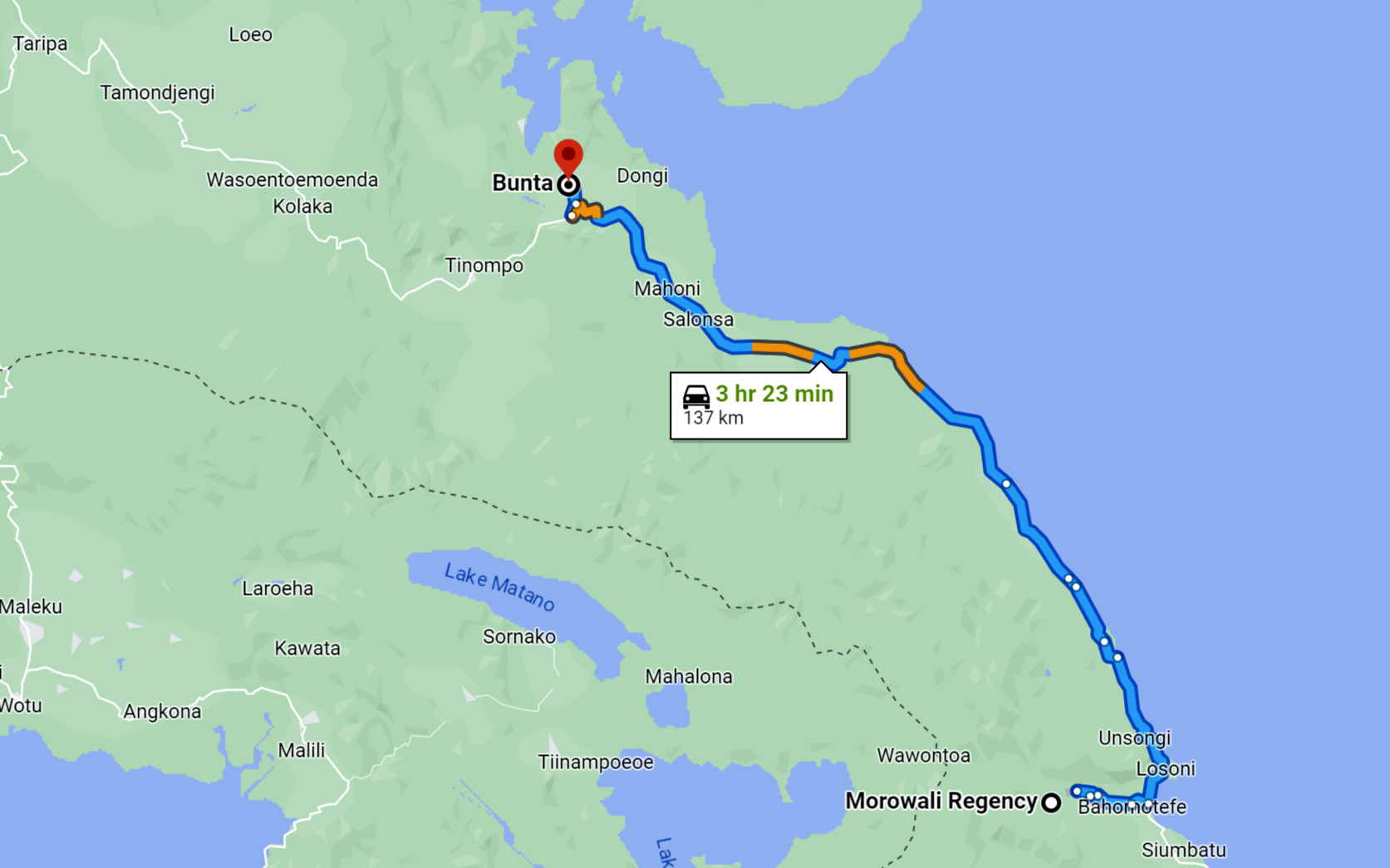

To this day, the National Workers Union has not established a local council in North Morowali. The SPN officials at PT GNI continue to coordinate either with the local council in Morowali or directly with central management in Jakarta. The road trip from Morowali to North Morowali takes three hours.

In Morowali, SPN local council bears the responsibility for over 3,000 union members, all of whom are employed at the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP). SPN is one of the largest unions in Morowali, but their involvement doesn’t consistently extend to coordinating with the union at PT GNI in North Morowali.

SPN Morowali Local Council was established in 2017, managing an industrial area employing over 80,000 workers. Katsaing, the former Chairman of SPN Morowali Local Council, who was running for the Labor Party, drew a comparison between his experiences organizing coal mining workers in Kalimantan and those in IMIP.

“In coal mining, the organization’s scope is smaller, and the level of understanding about union is higher. At IMIP, most workers are just starting their career, with approximately 75% being newbies and 25% experienced workers. These workers aren’t familiar with the concept of a union,” Katsaing explained. He added that educating and organizing these workers is a lengthy process, particularly considering the demanding work schedules in the smelting industry.

The distance between the local council of SPN in Morowali and PT GNI. (Google Maps)

In his assessment, SPN PT GNI is facing a challenging situation. The union was established in 2022 but has since grappled with numerous work accidents and other labor issues. In the midst of these challenges, the company initiated an aggressive crackdown on the union.

“The management is still chaotic, as the newly-formed union grapples with dissolution threats from the company,” Katsaing emphasized.

Minggu Bulu and Amirullah acknowledged the complexities of building and sustaining a union. The company’s aggressive anti-union stance has deterred many of PT GNI’s thousands of workers from joining the union. Additionally, not all members contribute dues to support the union’s operations, necessitating officials to rely on personal funds.

Amirullah disclosed that he had invested around Rp 5 million of his personal savings into union activities, a substantial amount equivalent to his 10 years’ worth of savings. “It’s necessary for operational expenses – printing forms, buying coffee or cigarettes for gatherings. It all adds up!”

Minggu Bulu echoed these sentiments, reflecting the profound consequences of the ongoing struggle. “When there’s a need to voice concerns, who can we turn to?” he pondered.

The Plight of Chinese Workers at PT GNI

Chinese workers make up a significant portion of the tens of thousands of workers at PT GNI.

In an interview with one former Chinese worker, identified as ‘V’ for safety reasons, who had previously served as a heavy equipment operator, a disconcerting narrative of the challenges faced by these workers unfolded.

V, among a group of Chinese workers, initially arrived in Manado, a major city in North Sulawesi, and then flew to Morowali, then traveled by land to North Morowali. It was only upon reaching Morowali that V learned of a tragic incident in which four of his fellow travelers perished while en route to PT Virtue Dragon Nickel Industri in Konawe, South Sulawesi, a nickel processing industrial park which is also partly owned by Chinese Company Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry.

“The boat capsized, and four people lost their lives that night,” recounted V. “At that time, PT GNI issued a warning not to disclose the incident. Anyone who spoke about it would be unable to return home.”

V experienced three wage cuts, each amounting to 20,000 CNY, equivalent to Rp 42 million. He suspected that these deductions were orchestrated, suggesting that superiors or the company deliberately sought reasons to diminish the earnings of Chinese workers. “We are penalized not for errors, but because these penalties benefit certain companies or individuals,” he asserted.

V was initially hired by PT GNI under a one-year contract, but then he was detained at a police station after voicing criticism of the company on WeChat, a popular social media platform among Chinese citizens. V had commented on a WeChat post highlighting the struggles faced by Chinese workers seeking to return home and the intimidation and violence meted out in response to complaints about extended working hours.

He was held at the North Morowali Police Station for 26 days, without the assistance of an interpreter or legal counsel. In order to secure his release, V was coerced into signing a document that prohibited him from making negative comments about PT GNI. Initially, he resisted, but the threat of prolonged detention compelled him to comply.

During his detention, V encountered another Chinese worker, identified as ‘Z,’ who had been apprehended 10 days after posting a photo of Chinese workers who died by suicide inside the industrial area on a WeChat group. Following his post, Z was reportedly beaten by PT GNI security personnel and detained at the police station. He showed torn skin on his temple as evidence of the assault. Z disclosed that the company deducted wages to cover his expenses while in custody, and these funds were relinquished to the North Morowali police station.

For V, working in Indonesia was a traumatic ordeal. In addition to enduring intimidation, he frequently heard about fellow Chinese workers who lost their lives. Some perished en route to Indonesia, died in workplace accidents, or resorted to suicide. V lamented, “Those of us who are still alive can share our stories, but who is there to speak for those who have vanished or passed away?”

Members of the SPN raise funds during a protest held in front of the National Police Headquarters, Jakarta, on May 11, 2023. They demanded the release of the PT GNI’s workers who they believed were unfairly arrested and detained. (Project M/Adrian Mulya)

Reportedly, there have been cases of accidents involving Chinese workers at PT GNI, such as falling from elevated platforms or being fatally injured by heavy loader equipment, witnessed by Indonesian laborers in the construction section of the power station. What is more concerning is the high suicide rate among the Chinese workers.

Chinese workers, through interpreters, have lamented unpaid wages that accumulated over a six-month period. These workers found themselves trapped in Indonesia, grappling with exhaustion, depression, and oppressive working conditions that did not align with the promises made before they embarked on this journey.

The information surrounding suicides and work-related accidents among Chinese workers spread rapidly through WeChat. One article referred to Indonesia as the “Island of the Dead,” featuring photos and details of two Chinese workers who took their own lives within three weeks in May 2022. The company’s response was not an investigation into the cause of these deaths but instead a prohibition on photographing and disseminating information about such incidents or other negative events in the future.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese workers encountered difficulties when attempting to return home. The company reneged on its promise to cover the costs of their repatriation. Vincent, a Chinese national who resides in Indonesia under the pseudonym for security reasons, initiated a fundraising effort with volunteers to assist Chinese workers stranded in the country.

Volunteers facilitated meals and connections to lawyers in China as Chinese workers transited through Jakarta on their journey home. Vincent’s group extended aid to over 500 Chinese workers from Sulawesi, a significant portion of whom were employed at nickel smelter companies. These workers, on average, were in their forties or fifties and were typically the breadwinners for their families.

They sought better income prospects when they came to Indonesia. However, the reality they encountered in Indonesia fell far short of the rosy promises. Many of these workers did not possess valid work visas, instead relying on tourist visas to stay in the country.

The conditions of their accommodations were far from ideal, with 10 workers sharing a single room. Food provisions varied from one company to another. Chinese workers often toiled for extended hours, some exceeding 12 hours per day. Despite their dedication, their wages often arrived late, with delays stretching from three to six months, and some individuals still struggled to collect all of their earnings upon returning to China.

Vincent’s exposure to the issues faced by Chinese workers in Indonesia began with a WeChat post. Vincent learned that the company deliberately detained several Chinese workers to prevent them from returning home immediately. The period between 2021 and 2022 saw limited flight schedules and exorbitant airfare costs to China. Prices soared, with a single trip totaling Rp100 million.

Prior to their departure to Indonesia, the company had assured Chinese workers of their flight back home. However, as flight prices soared, the company used various excuses to evade purchasing tickets. Consequently, a significant number of workers remained unable to return to China even after their employment contracts had concluded.

Typically, Chinese worker contracts last for six months or a maximum of one year. Upon contract expiration, these workers found themselves stranded in Indonesia without employment. Vincent observed, “They stay in Jakarta for 6-10 months but lack the financial means to cover hotel expenses. Their savings had been depleted as they were not paid.”

While staying at hotels in Jakarta, these workers continued to experience challenging living conditions. Some could only afford to subsist on Indomie instant noodles for an entire month. Despite the normalization of airfares and flight schedules, Chinese workers continue to see their wages withheld and mobility limited.

A bulldozer is demolishing land in Topogaro, Morowali, Central Sulawesi. PT Baoshuo Taman Industry Investment Group (BTIIG) is building a nickel processing industry covering an area of 7,817 hectares and impacting more than 10 villages in West Bungku and Bumi Raya Districts. (Project M/Permata Adinda)

Vincent noted, “Airfares have become more affordable, making it easier for Chinese workers to go home. Yet, the company maintains the authority to dictate when a worker can return to China. Chinese workers continue to experience various forms of oppression, with a lack of rigorous law enforcement oversight on the company.”

China Labor Watch shared multiple documents with Project Multatuli, detailing cases of work accidents at PT GNI. One such incident on March 8, 2023, involved the death of a Chinese worker in the smelter’s furnace section. The worker lost his life while operating an electric hoist, slipping from the third floor.

In an official notice, PT GNI placed blame on the Chinese worker, citing his “lack of awareness” about workplace safety. The document, written in Chinese, stated, “While operating the electric hoist, he did not pay attention to his surroundings and did not close the guardrail, causing him to step on air and fall from the third floor to the ground floor.”

Curiously, the official document did not entail an external investigation into the incident. Thus, the extent to which the accident resulted from worker negligence remained undetermined.

In cases related to the deaths of I Made Defri Hari Jonathan and Nirwana Selle, China Labor Watch alleged that compensation provided by PT GNI’s management to the workers’ families was sourced from penalty fines or wage deductions from numerous Chinese workers and labor supervisors. Seventeen Chinese workers faced penalties, ranging from 3,000 CNY to 20,000 CNY, culminating in a total of 129,000 CNY, or roughly Rp 273 million.

China Labor Watch questioned the degree of responsibility attributed to these workers in the accidents. Their attempts to monitor and document the deaths of Chinese workers at PT GNI were hindered by the company’s lack of transparency in reporting workplace accidents. To access information about these incidents, China Labor Watch relied on workers who shared details through social media.

The company’s lack of transparency was combined with control over the use of social media and restrictions on the freedom of expression of Chinese workers, as evidenced in V’s case. Workers who were caught uploading posts or images deemed detrimental to the company’s image risked penalties or illegal detention.

In our efforts to verify the accounts of workers detained at the North Morowali Police Station, we reached out to Head of the North Morowali Police Adj. Sr. Comr. Imam Wijayanto. He did not confirm or refute the reports, stating, “I had only taken office as police chief on January 14, 2023.”

Vincent continues to share the stories of Chinese workers in Indonesia through WeChat. He emphasized, “Without articles or news, no one will be aware of their condition. Even if they vanish or commit suicide, no one will take notice. These companies remain beyond the reach of accountability from both the Chinese and Indonesian governments. There are no consequences for their actions.”

“Forget about Passports, We are All Workers.”

The series of work accidents at PT GNI is not an isolated issue but rather reflects the broader challenges encountered in the nickel industry, which is concentrated in Sulawesi. Lala, a 32-year-old worker from Morowali, shares his experiences working in Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) and PT Wanxiang Nickel Indonesia, both situated along the Trans Sulawesi Road.

Lala’s stint at IMIP involved work in the molding division, molding ore, or nickel ore in liquid form. His work environment was rife with thick black smoke. He described the conditions: “I wear a head cover with a muzzle respirator mask, but it only lasts a few hours or even just 30 minutes if the smoke is heavy. The inside of my nose would still be filled with smoke. It’s that pervasive.”

Lala’s health deteriorated significantly as he contracted typhus for a month. However, the company fired him due to his inability to provide a sick certificate from a hospital. Lala strongly suspected that his illness was work-related, given his constant fatigue and bouts of breathlessness.

Work in his division involved three shifts divided into three squads. Over the course of three weeks, he rotated through morning, afternoon, and night shifts. Lala explains, “We work every day, and although there are days off, they don’t necessarily align with each worker’s preferred schedule.”

Accidents were not uncommon at IMIP. Lala witnessed instances where a Chinese worker’s leg was broken by a heavy load, and an Indonesian worker’s hand was crushed by a forklift car reversing. In another harrowing incident, a coworker suffered burns and blisters when exposed to hot nickel ore liquid.

“In our division, workers are required to wear pants outside of their shoes by default. But, after a meal break, my colleague forgot and, in a rush, proceeded to the printing house, making his legs exposed to the hot liquid,” recounts Lala.

A truck loads a pile of sand. Hot and fine dust of nickel ore is regularly inhaled by workers in the PT GNI area. The most common illnesses among workers are cough and shortness of breath. (Project M/Anonymous)

In addition to these “minor” accidents, not officially recognized as work accidents by the company’s safety department, Lala reported issues with his work protection uniform. Despite wearing a thicker uniform than workers in other divisions, it was not fireproof, and splashes of hot liquid could penetrate the clothing. This resulted in blisters and burns on his arms and back. Complaining to the safety department yielded only the response, “Such incidents are not categorized as accidents.”

Lala worked at IMIP for 1.5 years before moving on to PT Wanxiang Nickel Indonesia, where he became a dump truck driver. The work remains strenuous, and Lala cannot help but wonder about the plight of his colleagues in the production department. He said, “Even though my work is tough, my friends in production only get nights off. During my time at IMIP with its three-shift three-team system, it was incredibly demanding. So, what is it like for my friends there?”

A Jakarta-based organization, Trend Asia, conducted news monitoring and revealed that the nickel smelter industry in Sulawesi and Maluku experienced 68 work accident incidents, resulting in 76 injuries and 57 fatalities.

Arianto Sangadji, a former Managing Director of Yayasan Tanah Merdeka (YTM) in Palu, emphasizes that these work accidents in the nickel smelter industry are linked to companies’ efforts to minimize production costs. This reduction in costs affects workers’ wages and their overall safety.

“Corporations prioritize rapid expansion and profit over serious concerns for job safety. Consequently, they neglect work safety issues”, said Arianto.

Arianto, who authored a working paper titled “Natural Resource Governance in Central Sulawesi: Nickel-Based Industry Experience in Morowali” in 2020, published by the Corruption Eradication Commission and the Auriga Nusantara Foundation, explains that in Central Sulawesi, industrialization differs from the more stable process in Java. Grassroots movements in Sulawesi often originate from peasant resistance related to land disputes with plantation or mining companies.

Nevertheless, the past decade has witnessed rapid and substantial growth in industrialization in Central Sulawesi and other regions on Sulawesi Island, primarily due to Chinese investment in the nickel processing industry.

In 2022, Central Sulawesi became the province with the highest foreign direct investment (FDI) in Indonesia, surpassing West Java, North Maluku, and even DKI Jakarta. The total FDI reached a whopping USD 7.5 billion, equivalent to Rp 112.23 trillion.

)

Arianto attributes this massive investment to the transition of the nickel processing industry from China to Indonesia. Only China and Indonesia globally produce nickel pig iron (NPI), a low-cost raw material for stainless steel production. Indonesia boasts substantial nickel ore deposits, crucial for electric vehicle battery production. Thus, it enjoys a competitive advantage with cheaper NPI production costs compared to China.

In 2017, production costs for nickel pig iron in China ranged from USD 7,300 to USD 9,600 per metric ton. In contrast, production costs in Indonesia were substantially lower, ranging from USD 5,200 to USD 7,100 per ton. Notably, these production costs include work safety. Consequently, companies reduce costs by not providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and adequate job safety standards to workers.

Companies justify this by arguing that providing standard clothing or PPE would increase production costs, and workers should bear those costs themselves. Thus, companies may instruct workers to wear sandals and other non-standard clothing to reduce costs.

The nickel smelter industry is both capital-intensive and reliant on natural resources. Capital-intensive because it involves substantial investments worth trillions of rupiah. Additionally, it’s dependent on natural resources because nickel ore mineral deposits are concentrated in specific regions, including Sulawesi and Maluku.

The nickel industry is not as flexible as garment or textiles, which can relocate to areas with cheaper labor when facing labor issues. Due to the concentration of nickel ore reserves, it cannot easily move elsewhere.

Given this, the Indonesian government has designated the nickel smelter industrial area as a “national vital object” and a National Strategic Project to ensure investment security. Labor protests and disputes with the public are viewed as “threats”.

National Strategic Project is a designation for industrial or infrastructure projects that are considered necessary for economic growth and more equal development across the country. However, some of the projects classified as National Strategic Projects brought negative impacts to the environment, non-inclusive approach towards the locals, as well as detrimental to the indigenous ways of life. The locals who opposed them faced human rights violations.

PT GNI operates in the nickel industrial area managed by PT Stardust Estate Investment (PT SEI). The PT SEI area is designated by the Jokowi government as a “national vital object” with strict security supervision. (Project M/Muammar Fikrie)

“Because of the capital-intensive nature of the industry, the state’s level of protection for this area is very high, including by controlling the workers with a very flexible working employment contract,” explained Arianto.

The forms of control over workers can be observed, for example, in the company’s response to union busting and its control of Chinese workers. Furthermore, the Job Creation Law, enacted by the Jokowi government, facilitates the termination of employment for workers deemed resistant.

“In terms of capital interests, under such alienating circumstances, workers become easier to control. They become passive objects that are susceptible to control and suppression,” said Arianto. “I believe the cases of suicides among Chinese workers are related to the high psychological stress due to poor working conditions and extreme levels of exploitation.”

The strong anti-Chinese sentiment among Indonesian workers and residents in the industrial area is closely tied to the perpetuation of identity politics at the national level. For instance, during the 2019 presidential election, the issue of Chinese workers in Indonesia dominated and was intentionally emphasized by certain groups.

“Racial issues are propagated by those in Jakarta. Sentiments that in reality are nurtured by the elites, including the intellectuals,” Arianto continued.

The perpetuation of racial issues in local communities also benefits the company. They could downplay the cases of labor violations and workplace accidents, and at the same time intensify the issue of “horizontal conflict” between Indonesian and Chinese workers.

“The company has benefitted from the issue. It gave them a reason to increase the presence of security forces to anticipate ‘potential riots’,” Arianto noted.

Arianto highlights that we need to confront the issue with a class perspective instead of perpetuating identity politics. Both Indonesian and Chinese workers are members of the working class and are equally exploited by the capital-owning class. Labor unions have played a role in improving safety conditions for workers.

Protests in 2020 at IMIP regarding COVID-19 pandemic policies, wages, and work safety led to the dismissal of several union leaders. However, the demands of the labor movement were also gradually met. At PT GNI, the company began distributing PPE uniforms and reducing arbitrary wage cuts following labor protests.

Arianto maintains that the conditions at PT GNI today resemble those at IMIP in the past, where work safety was a critical demand of the labor movement. This persistence of the labor movement has been a driving force for improvement.

Therefore, there is a need to organize Indonesian and Chinese workers together through labor unions. This endeavor is challenging due to language barriers and other factors, but it’s crucial to instill class consciousness.

As Arianto aptly puts it, “Forget about passports; we are all workers. Not because we are Chinese or Indonesians, but because we are members of the working class.”

EPILOGUE

My last contact with Minggu Bulu took place on April 10, 2023, when I received the disheartening news that Minggu Bulu and Amirullah had been named suspects in the aftermath of the January 14 strike. That morning, Minggu Bulu arrived at the North Morowali police station alongside Amirullah and his lawyer. I asked about their situation and well-being, to which he replied, “We’re just dealing with it. What else can we do?” He attempted to put on a brave face.

Minggu Bulu had to enter the police room, and I exchanged greetings with Amirullah before leaving. After that, Minggu Bulu’s WhatsApp status reflected a somber mood, asking, “Is there still justice in this country?” The following day, I no longer received any messages from him.

I received information from SPN management in Jakarta that Minggu Bulu and Amirullah were immediately detained after the examination process concluded at 2 am. SPN, along with a team of lawyers, sent letters requesting the suspension of their detention.

Jumardin and the other detainees were unable to reunite with their families during Ramadan, having been transferred from the North Morowali Police Station to Poso Prison on March 16, 2023. Meanwhile, the legal counsel of the Morowali People’s Advocates Front (FARM) filed a pretrial application regarding the convictions of the 16 workers.

Starting from February 9, 2023, Dedi Askary, the Chairman of the Central Sulawesi National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM), sent letters to the National Police Chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo and Central Sulawesi Police Chief Rudy Sufahriadi, requesting the suspension of the suspects’ detention. These letters were ignored.

Members of SPN perform a theatrical performance while holding a protest in front of the National Police Headquarters, Jakarta, on May 11, 2023. (Project M/Adrian Mulya)

The number of prisoners remains unclear. Initially, the police mentioned 16 suspects plus 1. However, the defense team’s pretrial application listed 16 suspects. In the arraignment on April 17, 2023, the number changed again to 15 people.

When asked about the situation, the Head of Public Relations of the Central Sulawesi Police, Sr. Comr. Djoko Wienarto, and the Head of the North Morowali Police Adj. Sr. Comr. Imam Wijayanto, reported that there were 18 suspects and the case had been transferred to the Poso State Prosecutor’s Office. Among these suspects, 16 were charged with public violence, one with arson, and one with sedition charges. Notably, the deaths of two workers, one Indonesian and one Chinese, that occurred during the January 14 “clash” were not attributed to the 18 suspects. The case concerning these two deaths remains under investigation, according to North Morowali Police Chief Imam Wijayanto.

Agus Salim, a lawyer from FARM, mentioned that his team accompanied 16 people and was unaware of the other two suspects designated by the police.

Project Multatuli reached out to PT GNI’s public relations through email but received no response until the publication of this report.

Jumardin’s family contacted us after his transfer to Poso prison. Mulyati, Umar’s mother, still hasn’t had the chance to visit her son. The increasing distance between Poso Prison and their village, approximately 200 km or a 5-hour drive, has made the journey more challenging. Yulan, Umar’s sister, tearfully expressed her hope for her brother’s return, at least by the time Idul Fitri arrived.

Idul Fitri has passed. Umar and the other prisoners remain incarcerated.

Muammar Fikrie contributed to this report.

Translated into English by Devina Heriyanto.

The report is supported by JATAM (Mining Advocacy Network) and is part of the #Perburuhan (#Labor) series proposed and funded by Kawan M, Project Multatuli’s membership program which allows readers to be involved in editorial meetings and propose reporting ideas. The piece was first published in Indonesian.