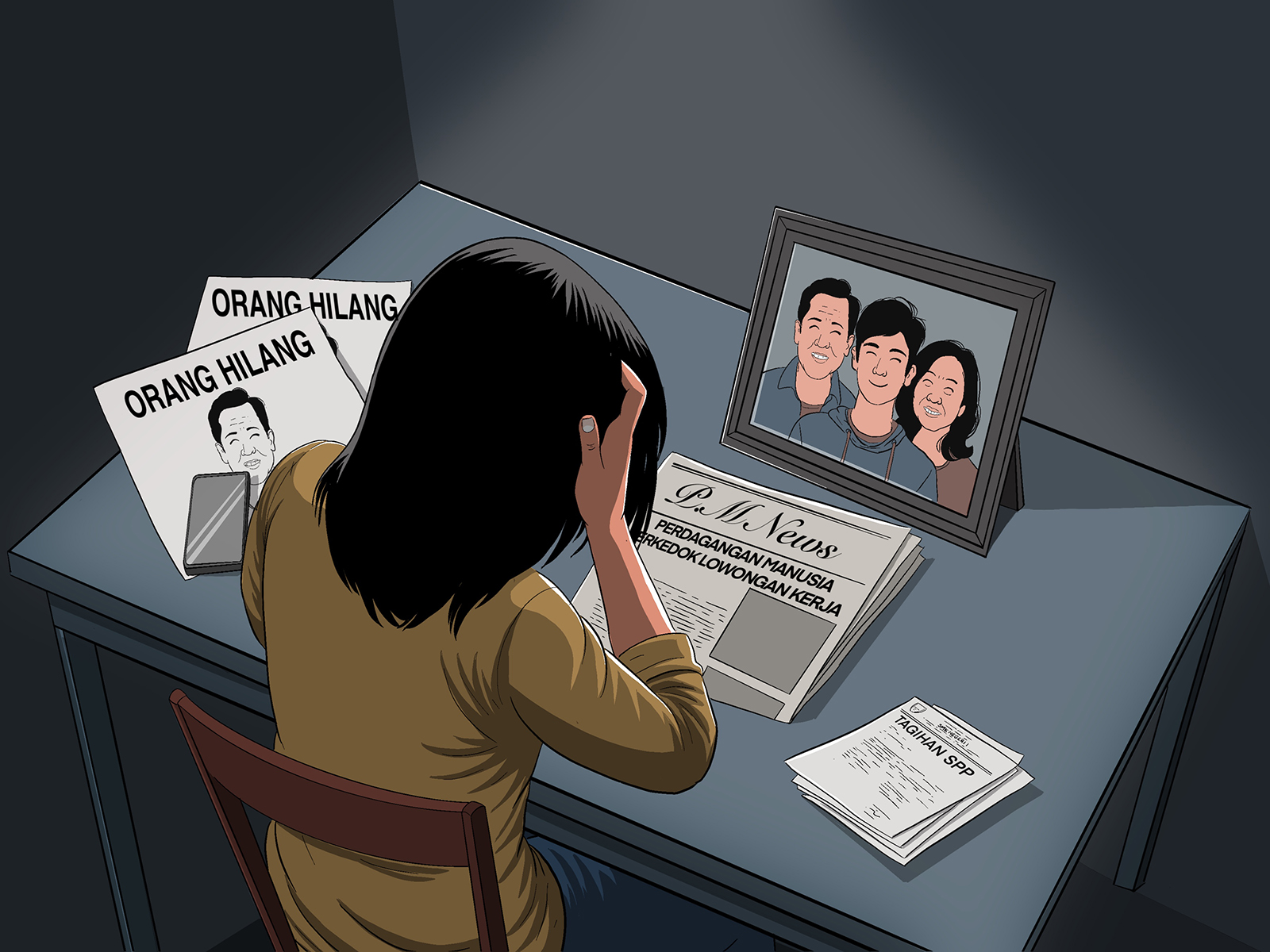

Three victims’ families are still waiting for their relatives to be repatriated from Myanmar, where they are enslaved in the online scam industry.

This transnational crime is linked to Chinese criminal networks. Although Indonesian authorities have arrested some local scam agents, others remain at large. Without decisive action against these syndicates, Indonesia risks becoming an attractive market for Chinese criminal groups, recruiting people to operate scam centers in Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Laos, and Thailand.

JAKARTA, Indonesia—For two years, the families of human trafficking victims have waited anxiously for the return of their loved ones, who have been forced into slavery in online scam operations in Myanmar. These families continue to hope the Indonesian government will intervene and rescue them.

“Please, Indonesian government. How much longer will our family remain abandoned?” asked Yanti, the sister of one of the victims still trapped in Myanmar.

Myanmar—along with Cambodia, the Philippines, Laos, and Thailand—has become a Southeast Asian hub for pig butchering scams. This form of long-term financial fraud involves perpetrators building trust with victims, often through fake romantic or friendship relationships, before convincing them to invest in fraudulent schemes.

As of March 2024, Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that 30 Indonesian citizens remain trapped in Myanmar.

“We truly understand the families’ concerns, and I will do everything possible to bring them home. However, the problem lies in accessing such a dangerous area. No foreigner has ever managed to enter it,” said Rina Komaria, Head of the Southeast Asia Sub-Directorate at the Directorate for the Protection of Indonesian Citizens, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Recruitment Pattern

Friend’s Deception

The COVID-19 pandemic devastated lives, leaving household finances in ruins. Many people were laid off, struggled to find new jobs, and became burdened with debt. This situation made some individuals easy targets for human trafficking syndicates.

These organized crime groups recruit victims through various methods. They post fake job advertisements on social media, posing as trusted institutions. They also exploit their own friends––as happened to Siska and her husband, Tito.

The couple’s nightmare began when Ahong, a friend, visited their home and tricked Tito into becoming a victim of human trafficking. As of August 18, 2024, Tito was still trapped in Myanmar.

“Ahong would eat and drink at our house when he was struggling financially. My husband trusted him. They were close friends—how could my husband think badly of him? And then, he deceived my husband,” Siska said.

In the past, Tito and Ahong worked for the same company. But later, Ahong moved to Thailand. When he found out that Tito had been laid off, he invited him to work at “a tech company” in Thailand, promising a monthly salary of Rp8 million (US$510)—a significant amount compared to Indonesia’s minimum wage of around US$286.

At first, Tito declined because he didn’t have money for travel expenses.

“But Ahong was persistent and even offered to cover the costs,” Siska said.

Siska recalled how Ahong reassured them: “Don’t worry, everything’s safe. There’s nothing strange. I’ll handle everything.”

“So my husband agreed. Our financial situation was bad, and he was stressed about our debts,” Siska explained.

In April 2022, after Ahong arranged the administrative and financial matters, Tito left for Thailand alone. At a Bangkok airport, someone claiming to be from the company—an associate of Ahong—picked him up. Tito stayed in a Bangkok hotel for three days, waiting for another worker, a man from Palembang.

On the third day, a company representative took Tito and the man from Palembang on a long journey through the jungle. When they finally arrived at the company, Tito saw Ahong again.

Soon after, Siska began having trouble contacting her husband—the company had confiscated his phone, allowing Tito to use it only twice a week.

Siska occasionally reached out to Ahong for updates, but over time, her husband told her to stop.

“Don’t contact Ahong anymore. If you do, it’s like killing me. He sold me to the Chinese to work as a scammer,” Siska said, recalling her husband’s words.

“At first, my husband thought he was still in Thailand. Later, he realized he was already in Myanmar,” she added.

Siska never discovered her husband’s exact location, and then Ahong disappeared.

“I’ve lost contact with my husband, and Ahong’s number is no longer active. But I’ve heard that Ahong has returned to Indonesia,” Siska said.

According to a May 2024 report by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Chinese criminal networks operating in Myanmar shifted their focus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initially, from 2017, these criminal organizations controlled illegal cyber gambling businesses along the Myanmar-Thailand border, with support from the Karen Border Guard Force (BGF), which is affiliated with the Myanmar military. In 2020, the Myanmar government shut down many of these operations in Karen State (now called Kayin State). However, following the military coup in February 2021, these criminal organizations resurfaced and expanded into running pig butchering scams.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, China closed its borders, making it difficult for these networks to recruit workers domestically. As a result, they began targeting workers from other countries, including Indonesia.

“Globally distributed human trafficking networks play a role in this process. Their task is to deliver job seekers to scam centers. And Myanmar-based criminal groups are the ones who pay them,” the USIP report stated.

Broker’s Promises

A panel of judges at the Bekasi District Court found Andri Satria Nugraha and Anita Setia Dewi guilty of human trafficking on February 5, 2024. The judges sentenced each of them to eight years in prison and fined them Rp200 million (US$12,763), with an additional four months in jail if they failed to pay the fine. The court also ordered them to jointly pay Rp600 million (US$38,292) in restitution to the victims, or serve an additional six months in prison if they do not pay.

Andri and Anita recruited and deceived dozens of Indonesians, forcing them to work as cyber scammers in Myanmar. Twenty victims recorded a video testimony about the fraud and torture they endured, which went viral on social media and prompted a response from President Joko Widodo.

On May 5, 2023, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, through the Indonesian embassies in Yangon, Myanmar, and Bangkok, Thailand, successfully evacuated them from Myawaddy, Myanmar. Four days later, the National Police’s Directorate of General Crimes (Bareskrim) arrested Andri and Anita at Sayana Apartment, Kota Harapan Indah, Bekasi Regency.

However, some of Andri’s and Anita’s victims remain trapped in Myanmar.

One of them is Pendi. His wife, Mona, is still fighting for her husband’s return to Indonesia.

The restaurant where Pendi worked went bankrupt due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving him with no choice but to work odd jobs. Sometimes, he worked as a motorcycle-taxi driver, and other times as a private driver. His income was barely enough to cover daily expenses.

One day, he met Andri Satria Nugraha and Anita Setia Dewi at Summarecon Mall Bekasi. The couple offered Pendi a job at “a technology company” in Thailand, promising a one-year contract with a monthly salary of around Rp10 million to Rp20 million (US$639 to $1,277).

They also promised to cover his flight, meals, accommodation, and other administrative costs. All that was required was proficiency in English and fast typing skills.

“They soon had a Zoom meeting, where Andri and Anita appeared along with eleven other victims. The departure process moved very quickly after my husband met them,” Mona said.

Mona grew suspicious because Andri and Anita never disclosed the name of the company, saying only that it was located in Bangkok.

“But my husband went anyway because he had good intentions—he wanted to provide for the family. So he accepted the offer to go to Thailand,” Mona said.

Andri and Anita arranged the departures in two groups. Pendi and four others—two women and two men—were part of the first group, which left Jakarta in July 2022. The second group departed from another location at a different time. Meanwhile, Andri and Anita stayed behind in Indonesia.

“When he arrived in Thailand, my husband contacted me. Someone from the company, who seemed to be in charge, picked him up. He looked Chinese but spoke with a bit of a Malaysian accent,” Mona said.

The company representative took the victims to a hotel in Bangkok, where they spent the night. The next day, they were driven 500 kilometers to Mae Sot, a city on Thailand’s western border with Myanmar, before crossing the Moei River. None of the victims realized they had been smuggled into Myanmar.

Once there, the company confiscated their passports and forced them to practice speed typing. They also restricted mobile phone use, making it difficult for Mona to contact Pendi.

“Three weeks later, my husband sent me a letter saying he had realized he’d been tricked. He asked me to report it to the Indonesian authorities,” Mona said.

Language Course Center

Yanti remembers Wahyu as an introverted person, determined to achieve his dreams. Ever since graduating from college, her brother had dreamed of working in South Korea. To pursue that goal, he enrolled in Korean language courses at the Korean Language Center Indonesia (KLCI) in Sukabumi—run by Latif Aliyudin.

“My brother took the Korean language test in Jakarta twice before he finally passed and got his certificate,” Yanti said.

With Latif’s help, Wahyu was almost sent to work at a manufacturing company in South Korea, but the plan was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the meantime, Wahyu took on odd jobs, with his last position as a part-time teacher, earning Rp600,000 (US$38) per month.

“Then the course reached out again and offered him another opportunity, asking, ‘Do you still want to work in Korea? Departures have reopened,’” Yanti recalled. “My brother agreed because it was his dream.”

KLCI Sukabumi requested Rp20 million (US$1,278) for Wahyu’s departure costs. His family helped pay in installments—first Rp3 million, then Rp5 million—until the full amount was covered. However, Wahyu never went. KLCI said that processing the visa and work permit for South Korea was still complicated.

As an alternative, Latif suggested that Wahyu take a job at “a Korean subsidiary in Thailand.”

“He said it would only be for three months, at most, before my brother could finally go to South Korea. Wahyu agreed because he was unemployed, getting older, and had already paid in full,” Yanti explained.

Latif introduced Wahyu to a man named Ardli Fajar, who arranged accommodation for Wahyu at the City Park Apartment in Cengkareng. In November 2022, Wahyu departed for Thailand.

After Wahyu moved, Yanti found it difficult to stay in touch with him. His phone was often inactive, and her messages would only show a single check mark.

“I tried messaging him, but it would take three or four days—sometimes even a week—before he replied. He said he was healthy. I stayed positive, thinking maybe he was just adjusting to the work there. By December 2022, I still hadn’t heard much from him,” Yanti said.

Months passed, and Yanti completely lost contact with her brother. The family grew increasingly worried, especially as news reports about fraud and human trafficking in Southeast Asia began to surface.

“One day, I sent him some news articles and asked about his location and how he was doing. Two weeks later, he finally replied. But his messages sounded strange, like he was scared,” Yanti recalled.

Wahyu told her that he had been smuggled into Myanmar through Thailand. He wasn’t working at a manufacturing factory but had been forced to work as a cyber scammer—and he wasn’t getting paid.

“Brother, just escape,” Yanti urged.

“I can’t. I’m trapped behind a mountain.”

“Are they torturing you?”

“Yesterday, they electrocuted me,” Wahyu replied. “Don’t tell Mama. I’m afraid she’ll get sick from stress. Just pray for me to stay strong here.”

Days in the Camp

In Myanmar, Indonesians forced to work as pig butchering scam operators endure extremely long, inhumane working hours—17 to 20 hours a day with only 30 minutes of rest, without holidays or pay.

The cyber fraud organizations force these enslaved workers to scam 100 people each day, primarily targeting citizens from the United States, Canada, and Australia. If they fail to meet their targets, their working hours are extended, or they face physical punishment. These punishments include standing for hours, running 30 laps around a soccer field while carrying a water-filled gallon, doing hundreds of push-ups, being hit with blunt objects, whipped, or even electrocuted—depending on the severity of their failure.

After being electrocuted by the syndicate, Wahyu’s body was covered in bruises, and he struggled to walk.

“His legs hurt, so he had to walk slowly. But even in that condition, he comforted us,” Yanti said.

Yanti recalled her brother telling her: “Don’t worry about me. I wore layers of clothes—thick ones. So when they electrocuted me, it didn’t feel as bad.”

“But being electrocuted is still being electrocuted—it breaks my heart,” Yanti said.

The victims have lost all choice and control over their lives. The company forces them to keep scamming, even though it goes against their conscience.

Siska recalled her husband Tito saying: “Bu, I can’t stand lying to people. When I look at the photos of the people I’m supposed to scam, I see their children and families. It makes me think of you and the kids at home. That’s when they beat me.”

“So my husband just accepted it when they beat his thighs with iron rods and beams until they bruised. Eventually, they hit him on the head. He wanted to fight back, but he couldn’t,” Siska said.

The Pig Butchering Scam

The pig butchering scam is a type of online investment fraud with two stages.

The first stage, known as “fattening the pig,” involves building trust between the scammer and the target. Scammers use fake identities to approach their targets on social media. In some cases, they steal real people’s identities.

The scammers often pose as glamorous, wealthy individuals—attractive, upper-class men or women—who flaunt luxury goods, enjoy horseback riding, travel the world, and drive Ferraris. They use these personas to lure wealthy targets.

Initially, the scammer is warm and friendly, engaging the target as if they’ve known each other for a long time. Once trust is established, the scammer introduces an investment opportunity, promising high returns through fake cryptocurrency trading platforms set up by the company.

The second stage, “butchering the pig,” begins when the scammer embezzles the target’s money. Once the target has invested large sums, the scammer vanishes, along with the investment platform, leaving the target in financial ruin.

But not all scams go as planned.

If the scammer fails to deceive the target, the criminal groups may extort the scammer’s family. For instance, the company might demand a ransom, promising to release the operator if the family pays.

The syndicate once demanded Rp150 million (US$9,560) each from Mona and Yanti for the release of Pendi and Wahyu. Similarly, they asked Siska for US$10,000 to free Tito. When the families couldn’t pay, the company threatened to sell the victims to other criminal groups.

Siska remembered Tito saying: “They sold me to a new company. They confiscated my phone. I can’t take it anymore. Please prepare US$8,000.”

“My husband called me, crying. He couldn’t endure it any longer. The punishments at the second company were even worse. But where was I supposed to get that kind of money?” Siska said.

Mona also had no choice but to accept that her husband would be sold to another company. On average, victims were sold more than twice.

“I asked my extended family for help, but I couldn’t raise that much money. I reached a point where I knew there was nothing else I could do. If my husband was going to be sold again, I just had to accept it,” Mona said.

“We’re also scared. Even if we pay, there’s no guarantee they’ll come home. If not, we’ll just end up in debt,” Yanti added, thinking of her brother, Wahyu.

But the company doesn’t care whether the families have money or not—they just want payment.

Yanti once told the company she couldn’t afford to pay.

“They told me, ‘If you can’t pay, we’ll take him to an underground prison,’” Yanti said.

“At that point, we didn’t know my brother’s condition. We feared the worst—thinking he might die,” she added.

Demanding Repatriation

Transnational crime has a domino effect. The victims’ families—mostly wives—not only suffer emotionally but also bear the financial burden alone.

Siska works tirelessly to support her family and ensure her two young children get enough nutrition.

“Now I have to work harder than ever. In the morning, I run a laundry service from home,” Siska said. “In the afternoon, I work at a clothing store until 10 p.m. If I’m not too tired, I stay up ironing until dawn.”

Mona is in a similar situation, now working as a domestic worker to support her family. Her and Pendi’s two children had to drop out of college to help with the family’s financial struggles.

“They’re working now. We help each other. I feel guilty that their father’s situation has burdened them, especially at such a young age,” Mona said.

These women have taken on multiple roles as they continue to fight for their families. They’ve appealed to the police, BP2MI, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Commission on Human Rights, and even visited the House of Representatives. Several civil society organizations have supported them, yet they still have no clear answers.

“The government keeps asking us to be patient and wait. We don’t know what the obstacles are—we’re just housewives who don’t understand diplomacy,” Mona said.

“The police still haven’t arrested Latif. They’ve summoned him twice. They should bring him in by force,” Yanti added, referring to Latif Aliyudin, the owner of the Korean Language Center Indonesia (KLCI) in Sukabumi.

“My husband even asked me to seek financial help from people in the village. He said, ‘If the government can’t bring me home, we’ll have to prepare the ransom ourselves,’” Siska said.

Exhausted from fighting alone, the women started a joint movement called “Jerat Kerja Paksa” (Forced Labor Trap), a self-help initiative supporting victims and families of modern slavery in Southeast Asia.

They’ve shared their struggles in public forums and, most recently, sent an open letter to President Joko Widodo on June 26—World Day Against Torture—through the State Secretariat. In the letter, they urged Jokowi and his cabinet to address human trafficking urgently.

“No one deserves to be tortured, and no one should have the right to torture others,” the letter stated.

Meanwhile, the Directorate of Protection of Indonesian Citizens at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said they have not yet been able to rescue the victims.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said they have tried several approaches, including seeking assistance from the Myanmar government, approaching the government of the People’s Republic of China (details of which they cannot disclose), and communicating with the Karen Border Guard Force that controls the Karen State.

“The (Myanmar) government can’t reach the victims because their location is too close to the conflict zone,” said Rina Komaria, Head of the Southeast Asia Sub-Directorate of the Directorate of Protection of Indonesian Citizens at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Myanmar has been engulfed in a prolonged civil war, which intensified after the military staged a coup against the civilian government in February 2021. The conflict has spread across several regions, including Shan, Kachin, Karen, Rakhine and central Myanmar.

“About five to seven people are in the Hpa-An area. It’s extremely remote and close to the heart of the conflict. Not only is it difficult for Indonesians to reach, but even Myanmar authorities struggle to access the area,” Rina added.

Hpa-An is a major city in Karen State, a region that has drawn the attention of international human rights activists due to its role as a hub for transnational criminal operations.

Several areas in Karen State are suspected of being bases for cybercrime, online gambling, illegal casinos, and human trafficking. These include Apollo Park, Yatai New City (Shwe Kokko), Yulong Bay Park, KK Park 1 & 2 (Dongfeng), Dongmei Park and Myawaddy Town.

According to a report by Justice For Myanmar, these transnational criminal operations are controlled by Chinese criminal networks in collaboration with the Karen Border Guard Force (now the Karen National Army). One of the most prominent figures is Wan Kuok-Koi, also known as Yin Gouju or “Broken Tooth,” a former leader of the 14K Triad criminal group and the main investor in Dongmei Park.

Myanmar’s complex political situation is believed to limit the Indonesian government’s options. The success of repatriating Indonesian citizens relied heavily on establishing communication with local power networks.

“There’s no standard method to extract people from these areas. The complexity comes from the presence of numerous armed groups. And those we attempted to contact don’t have the authority to approach these companies directly,” Rina added.

Besides rescue efforts, Rina said the Indonesian authorities must apply preventive measures.

Rina said the Ministry of Foreign Affairs “always coordinates” with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and “always coordinates” with the Ministry of Communication and Information to remove false recruitment posts from social media. However, she likened the problem to mushrooms: “Cut one, a thousand grow.”

According to the Indonesian Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Culture (Kemenko PMK), 3,703 Indonesian citizens became victims of human trafficking (TPPO) between 2020 and March 2024, coerced into working as online scam operators.

These individuals were trafficked to Cambodia, followed by the Philippines, Thailand and Myanmar. The victims primarily came from North Sumatra, North Sulawesi, West Kalimantan, Central Java, West Java, DKI Jakarta, East Java, Bali, and Riau.

“Prevention isn’t our main responsibility. Our core work focuses on handling cases and providing services to Indonesian citizens facing problems abroad. If prevention efforts in Indonesia aren’t properly addressed, the Directorate of Protection of Indonesian Citizens will just keep ‘sweeping’ and ‘washing dishes’—because the cases will keep coming,” Rina said.

The names of all victims and their families in this article have been changed, and some details have been omitted to protect their identities.

This article is part of our ongoing #IndonesianMigrantWorkers series, supported by Project Multatuli’s readers.

This piece is translated and contextualized by Anne Parisianne