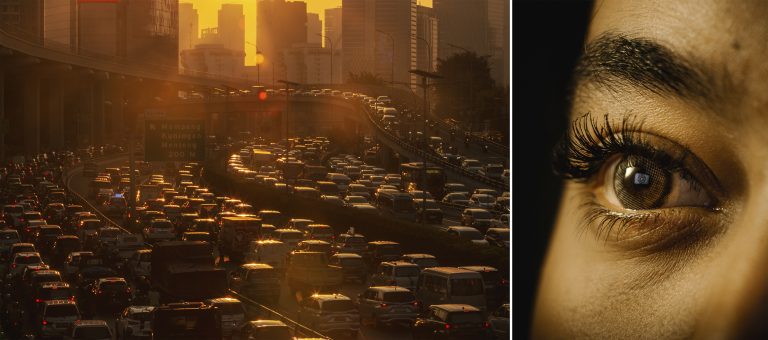

In Dieng, the push for geothermal energy as a green solution for Indonesia is clashing with the livelihoods of local farmers like Haryati. As state-owned Geo Dipa Energi expands its operations, residents report contaminated water sources, destabilized soil, and declining crop yields. All of it highlights the delicate balance between the need for renewable energy with environmental health and agricultural sustainability, raising questions about the true cost of Indonesia’s next big transition.

On the pathway down the hill, Hariyati* appears indifferent to the panorama of mist-draped green hills–a signature of Dieng, a famed tourist destination in Central Java, Indonesia.

Her sharp eyes scan the fields for chayote, a pear-shaped vegetable, and leftover potatoes, which she gathers for her family.

“Potatoes are Dieng’s treasure,” said the 35-year-old farm laborer who Project Multatuli interviewed after a hard day’s work.

For more than a decade, Hariyati has tended potatoes on land owned by her neighbor in Pawuhan Village, Batur District. Her daily wage ranges from US$2 to US$3.5, for about five working hours. During harvest season, about once every four months, she can earn an additional US$32.

“Nowadays, the harvest has declined,” said Hariyati, adding, “It’s hard to find water.”

The main reason is the dry season, she said. However, the past five years have been different, with water resources seeming to dwindle faster than ever. For farmers, the shortage of water supply can negatively impact soil health by lowering moisture levels, which hinders crop growth.

In Pawuhan, residents are no longer able to pump water from the ground for household consumption. They fetch it from Mount Prau, about 8 kilometers away. Rows of water pipes stretching through houses, inns, and main roads have become a common sight in Dieng.

Hariyati, a lifelong resident of the village, believes this situation is linked to the drilling for the geothermal power plant operated by PT Geo Dipa over 15 years ago.

“[The groundwater] smells, and it even tastes salty,” she said, noting that it now has an odor similar to the gas emitted by the power plant.

Pawuhan is flanked by well pads from the state-controlled geothermal energy company. Between the settlement, the potato fields, and the well pads, there are Geo Dipa’s offices, as well as pools that store water from the geothermal production wells.

“My parents were farmers, we’ve been farming here for a long time. We’ve never experienced this before,” Haryati said.

Indonesia has the largest geothermal energy reserves in the world, about 24 gigawatts (GW), accounting for 40% of global reserves. The government promotes geothermal energy as a key solution for sustainable power, aiming to reduce emissions by 32% in the next 6 years. Currently, the country operates 16 geothermal power plants with a total capacity of 2.4 GW – making Indonesia the second largest geothermal producer after the United States.

Toxic air that hurts crops

About 500 meters behind Geo Dipa’s office in Pawuhan, Aziz is checking the water flow from a pump for irrigating fields. At the spot near where Aziz is standing, a strong, rotten egg-like odor is noticeable. Oily, black water streams out. “It’s been like this for more than a year,” said the 24-year-old farm worker, pointing to the gush.

Besides the strong odor emanating from the flow, the water Aziz pumps from the river is also warm, in contrast to the region’s typically cool, midday climate. Nearby, there is a pool of water covered in bubbles and rising steam, resembling a hot spring. The same sulfurous smell fumes from the pool.

Aziz says that residents are forced to continue using groundwater in areas near the suspected contaminated river for potato farming.

“Sometimes we have crop failures and [overall] the yields have decreased. As you can see there, there are many yellow spots on the mulch plastic, and on the soil, and even the leaves turn yellow [before they should do],” he said.

“But, on different occasions, some plants do succeed.”

Residents have complained about the water contamination to Geo Dipa, but the company has taken no action, he said.

“I’m not sure about compensation; the landowners understand that better. But [the contamination] damages the farmers’ crops, especially in a dry season like this.”

Based on the resident’s knowledge, Geo Dipa’s only action has been to put up warning signs about the hazards of gas. The company did not respond to Project Multatuli’s repeated requests for comment.

From field observations taken by Project Multatuli, the warm water with a gassy stench spreads out over roughly 300 meters in the village, home to about 1,000 residents. However, murky brown water can still be found in the ponds on residents’ farmland.

Meanwhile, the pungent odor can still be detected in a kilometer’s radius, especially in the early morning hours.

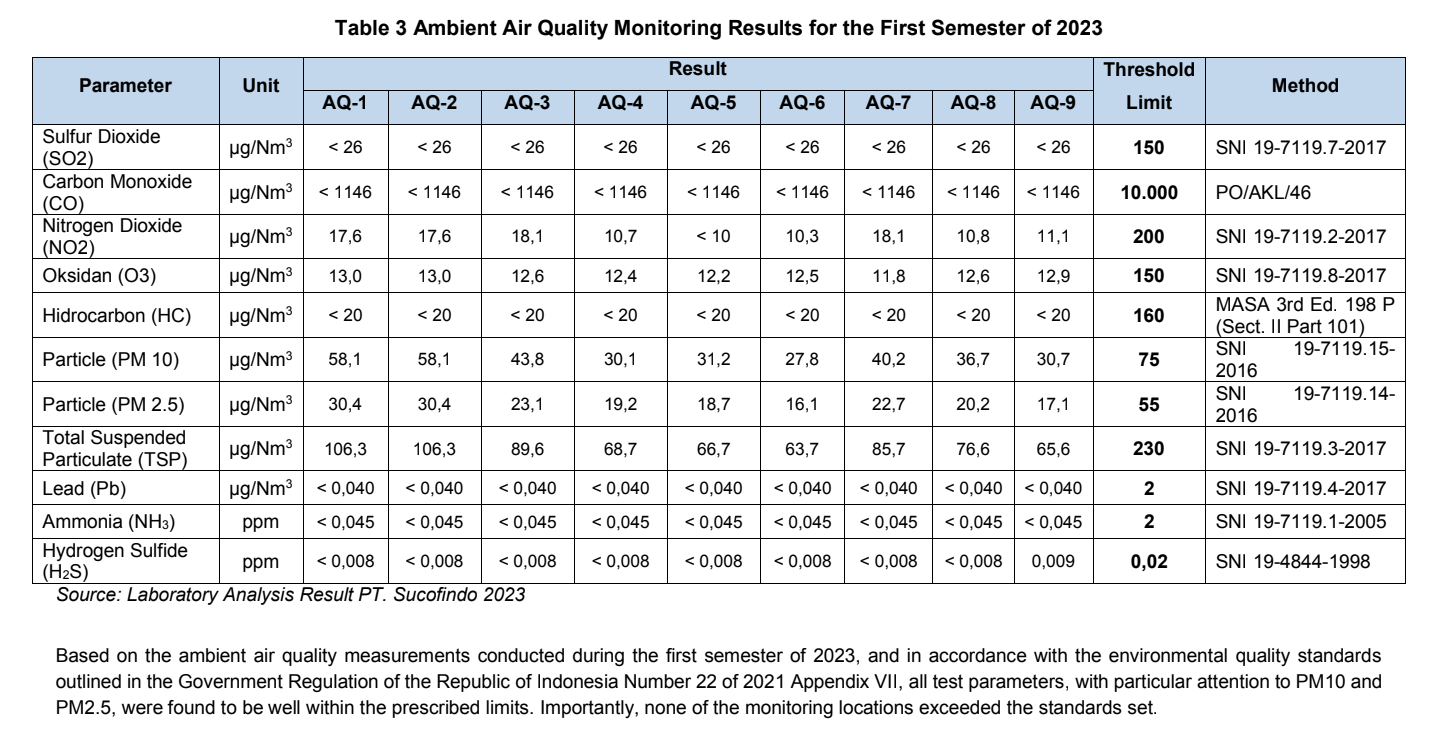

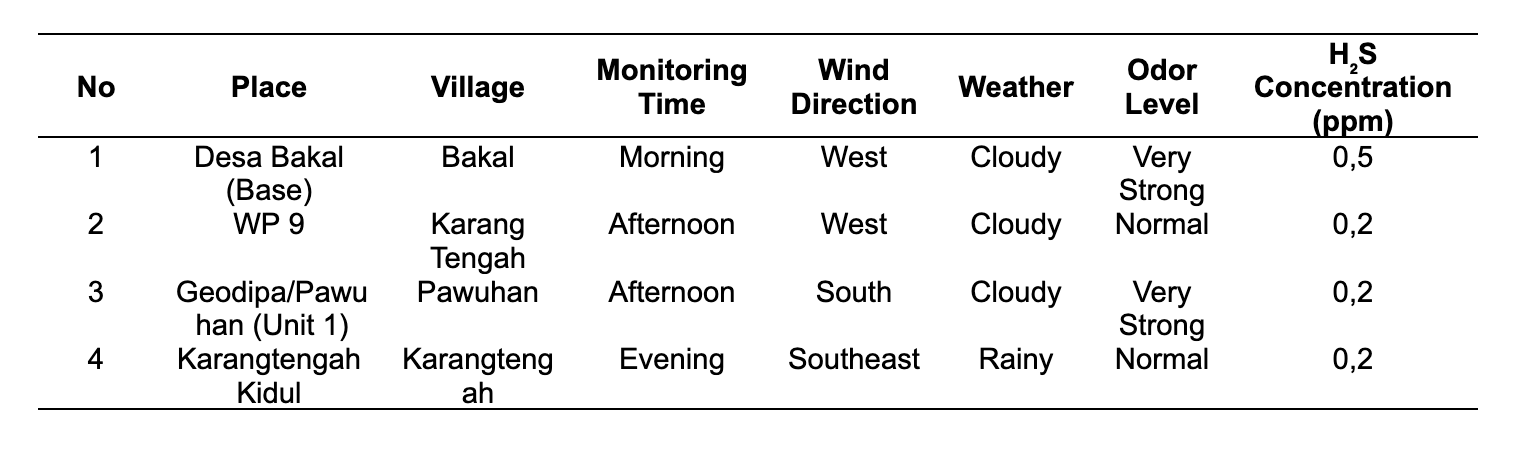

Last year, Geo Dipa conducted air quality tests around the well sites, power plant, and their office in Dieng. The test results showed that these areas were free from pollution.

However, earlier this year, Bambang Catur Nusantara, a researcher from the non-governmental organization Mining Advocacy Network, found that air pollution levels, particularly the H₂S (hydrogen sulfide), in Pawuhan exceeded safe limits.

According to a 2020 study in Poland, wind speed and direction are essential measurements for understanding air quality dynamics in a given region. Wind plays a crucial role in the movement and dispersion of air pollution, which can lead to varying air quality test results across different locations.

In a simple air pollution test using a Gastec GSF 400 FT with an H₂S tube conducted in February, the toxic gas levels in Pawuhan were found to have reached 0.2 ppm (parts per million). This concentration exceeds the safe limit set by Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment Decree, which is 0.02 ppm.

Catur conducted a similar test again in July, and found concentrations of H₂S in Pawuhan had reached 2 ppm.

“This test is quite simple and maybe [for some] considered less valid. But, air pollution, especially H₂S, is very easy to detect by smell. When there is a distinct smell of clean air, then there is something [wrong] there,” said Catur.

Soil and water instability

Geothermal power plants extract hot fluid from depths up to 3,000 meters, using production wells to generate steam that powers turbines. In Dieng, silver steam pipes, 40 centimeters in diameter, run through residential areas and farmland, encircling Pawuhan village.

To maintain the supply of geothermal fluid, injection wells return hot water to the earth. This circulation process highlights geothermal energy’s environmental benefits and lower carbon emissions compared to coal.

As a major coal producer, Indonesia outputs about 600 million tons annually, with 400 million tons exported. In response to environmental concerns, the country aims to reduce coal reliance by transitioning to cleaner energy and phasing out older plants.

However, the push for increased geothermal production has led to the introduction of fracking, a technology that makes the soil more permeable and increases the power that can be generated but raises earthquake risks. Residents in Karangtengah of Batur district, near a well pad, often experience moderate magnitude tremors.

“People here know that if there’s an earthquake, they immediately check if drilling is occurring. And almost always, it is,” said Ahmad Habib Hutomo, 50, a potato farmer in the village.

Earthquakes could occur one or two times a month, lasting up to a minute, Habib added. There has been no serious damage to his property and farmland from the tremors, though the villagers have been left traumatized.

The Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) frequently attributes the earthquakes in Dieng to the active fault lines beneath the highlands. These include several earthquakes reported by the media, such as a magnitude 3.1 earthquake in September 2022, a series of 16 tremors in January 2023, and a 2.6-magnitude quake in March 2024.

But, the link between geothermal exploration and earthquakes, known as induced seismicity, has been well-documented by researchers worldwide. In other research, geothermal activity in areas with active faults can also lead to land subsidence.

According to Indonesia’s 2017 Earthquake Source and Hazard Map, Dieng lies above four active fault lines that affect the region’s geological and volcanic activity.

Bosman Batubara, a geologist at Utrecht University, noted in his study on geothermal energy’s environmental impact that these quakes typically measure below 5 on the Richter scale. Similar induced seismicity was found in the 2006 quake in Basel, Switzerland, which led to the termination of geothermal activities due to public safety concerns.

A 2014 documentary chronicled the devastation in farmlands near the Mataloko geothermal plant operated by PLN in East Nusa Tenggara. There, small holes filled with mud and steam appeared, expanding until they swallowed five hectares of rice fields, leaving them barren.

This subsidence occurs when the soil loses density, destabilizing the land and causing it to dry out in a process called desiccation. As Bosman’s analysis suggests, such conditions heighten the risk of landslides, especially during the rainy season.

In October 2023, a coalition of residents living near geothermal sites sent a warning to the BMKG about the earthquake threat posed by geothermal activities. The letter was also forwarded to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK). As of publication, Project Multatuli has yet to receive comment from the ministry on a letter by the coalition.

***

Geothermal projects use large quantities of water, putting local residents’ water supplies at risk. According to Geo Dipa, the size of wells in Dieng are classified as medium to large, dictating the water needed for injection and fracking.

A 2020 study by Rigsis Energy Indonesia, estimates that wells drilled to a depth of 3,000 meters, nearly the height of Mount Fuji in Japan, require about 2,322 cubic meters of water, with reserves needing to be 300 percent of that amount.

Another study by the Central Java branch of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment calculated that geothermal operations need 40 liters of water per second—about 6,500 to 15,000 liters—to produce 1 MW of electricity. This is roughly equal to the daily water usage of 300 people (50 to 100 liters per day according to WHO).

Fracking also increases groundwater contamination risks from hydrothermal solutions containing arsenic, lead, and boron. A 2021 study at a geothermal plant in Mexico found that chemical buildup from geothermal activities near farmland, raising concerns about soil contamination and plant toxicity.

Silica (SiO2), which makes up 65-75% of geothermal fluid by weight, is another concern. In a 2015 study published in the journal Geothermics, researchers found that high levels of silica are present in brine (hot water) that emerges during drilling. Excess silica in soil can change its ability to hold water. While silica can act as a nutrient for some plants, too much can disrupt the absorption of other nutrients.

High silica content and other hazardous concentrates can be generated during well-testing, a process to assess productivity and safety before energy production. However, well-testing often caused detrimental effects on local crops.

A farmer in Karangtengah, Habib, said whenever a company conducts well-testing, farmers’ potato plants near the well site show severe signs of drying out, exhibit burn marks, and then eventually die within a couple of days.

“As far as I learned, during the well-testing, the steam that is released forcefully travels to a considerable distance, up to a kilometer, depending on the wind direction. If the wind blows east, plants in that direction are affected and die off,” he explained.

Some residents have filed a complaint to the company, but their losses were not addressed. The company reportedly asks for concrete evidence, such as certified laboratory tests to process any compensation claims.

“Why should the residents bear the burden of such lab tests? We are the ones suffering here. We know that every time well testing occurs, the plants die, and it happens repeatedly. If they conduct 20 well tests, that means 20 areas of crops will die,” Habib said.

Hydrogen sulfide exposure on land and residents’ health

In March 2022, a gas pipe in Pawuhan leaked, resulting in the death of one worker due to hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) poisoning. Eight others were hospitalized, while dozens, including local residents, suffered injuries and nausea.

Geo Dipa attributed the leak to an equipment malfunction at the wellhead.

In June 2016, an explosion occurred at a well pad in Pawuhan, due to the release of a gas safety cap during maintenance. Geo Dipa reported that six workers suffered from severe and minor burns.

However, the residents had to endure other losses. The explosion created a 10-meter-wide, one-meter-deep hole on one farm and destroyed several crops, leading to failed harvests for hundreds of households.

Geo Dipa claimed to have compensated 500 of 623 affected residents, with payments ranging from $45 to $12,200. Most residents received less than $70 for 100 square meters of farmland. According to the company, this amount was determined by a Public Appraisal Service Office (KJPP) study.

“They compensated us, but we’re still at a loss. Farming involves more than just the harvest; there are costs for seeds, fertilizer, planting, and wages. The compensation took a long time and wasn’t much,” said Habib.

He said that some farmers had borrowed money from the bank for production. Typically, they could divide their earnings from the harvest to pay off debts and cover daily expenses. Because of this incident, the farmers had to use the funds from the company only to pay off debt without receiving any additional benefits.

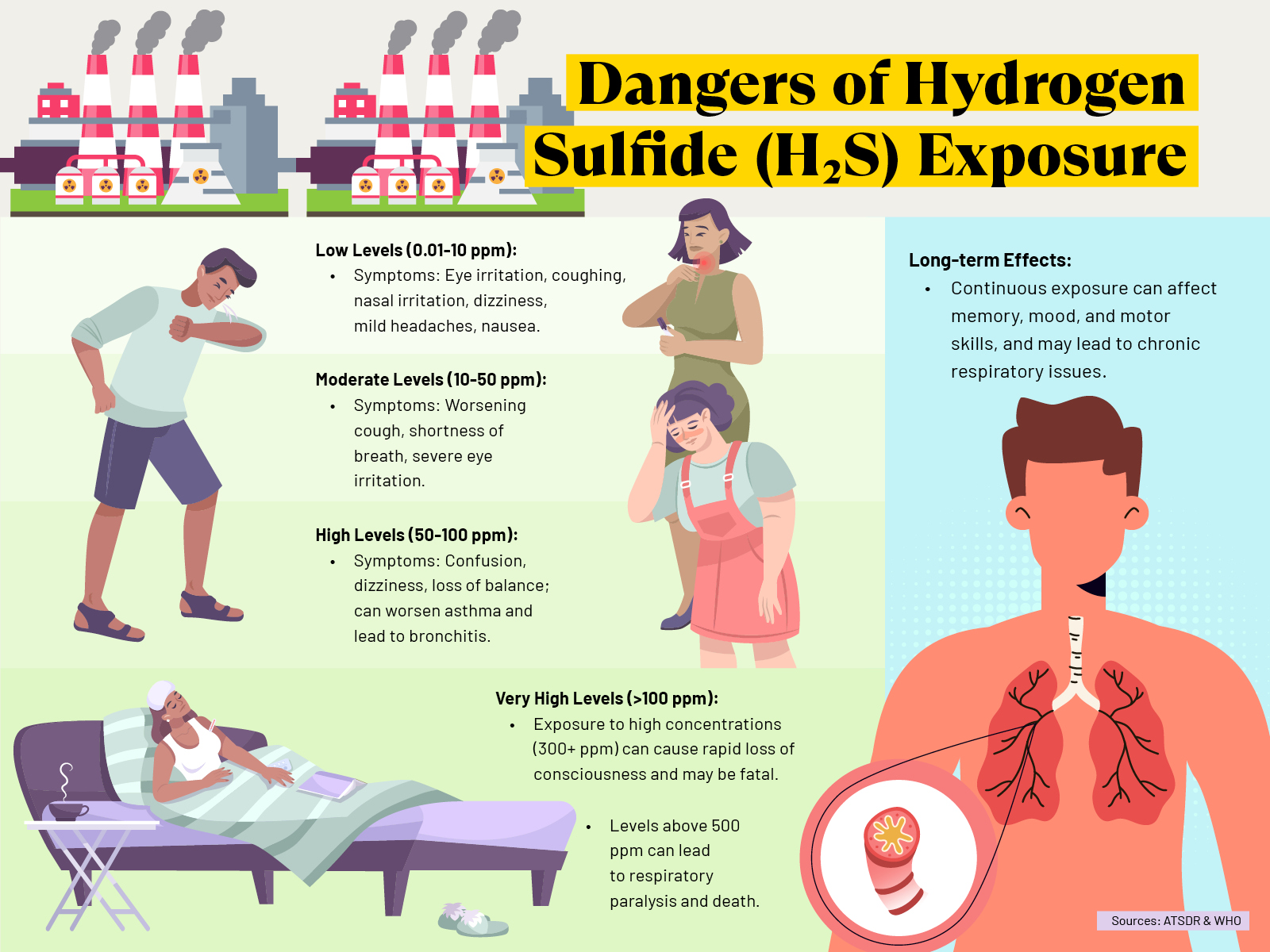

One of the ways hydrogen sulfide forms is from the reaction of sulfur in rocks and minerals with hydrogen found in geothermal fluids. High-temperature geothermal exploration releases H₂S into the atmosphere through gas and hot fluids. H₂S can settle in air, water, soil, and vegetation.

***

Geothermal resources in Dieng have been managed by Geo Dipa since 2002, when the company took over the management of the 55 MW power plant as a joint venture between two state-owned companies in gas and electricity, Pertamina and PLN. Geo Dipa reportedly oversees up to 40 production wells across Diengs’ Banjarnegara Regency and Wonosobo Regency. However, currently, only five wells are operational, generating about 20-25 MW.

In 2019, Geo Dipa announced plans for drilling expansion and construction for PLTP Dieng 2 & 3, with a capacity of 55 MW each. The company is said to have obtained environmental permits for the expansion plans.

But the extended plans have raised concerns about potential health impacts from H₂S exposure among local residents.

According to the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, continuous exposure of H₂S can pose long-term health risks, including chronic respiratory issues such as bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Additionally, high levels of H₂S exposure have been reported to cause diarrhea.

Data from Indonesia’s Statistics Bureau for Batur District, where Pawuhan and Karangtengah Villages are located, and Banjarnegara Regency reveal fluctuations in rates of pneumonia, tuberculosis (TB), and diarrhea from 2018 to 2023.

In Batur, pneumonia cases peaked at 338 in 2019, TB cases reached 18 in 2020, and diarrhea cases numbered 1,420 in 2021. Batur District has a population of 40,655, while Banjarnegara Regency’s population totals 1.4 million.

Dicky Budiman, an epidemiologist and environmental health expert from Griffith University in Australia, highlights that health issues related to H₂S exposure are often overlooked due to limited medical diagnostics.

“Many, especially in poor and developing countries, assume there is no problem because symptoms are general and can resemble other illnesses, leading to a downplaying of risks. There might also be a deliberate oversight, saying symptoms to other causes,” Dicky said in a phone interview in mid-September.

Dicky said that H₂S can be detected through blood, urine, and breath tests, but these must be conducted shortly after exposure due to the gas’ rapid decomposition in the bloodstream.

“Even breath tests are effective only if conducted within an hour of exposure,” he said.

Project Multatuli tried several times to contact the Batur Community Health Center in Pawuhan for information on specific health checks for H₂S exposure but received no response.

Periodic monitoring remains feasible, including lung function tests for at-risk individuals such as industrial workers, children, and the elderly, Dicky added.

“The effects of this toxicity are not only about immediate health issues but also about creating an uninhabitable environment. In other countries, living close to gas pipelines is prohibited. This is a significant issue here in Indonesia,” he said.

Potato production and the lost economic potential

Dieng potatoes have become a prominent product in both local and international markets. Known for their sweeter and softer flavor compared to other varieties, they are also recognized for their durability, making them well-suited for distribution.

In terms of trade, Indonesia’s potato exports encompass both fresh and processed forms. In 2021, fresh potatoes dominated the export market. Singapore was the top destination for Indonesian potato exports, valued at US$150 million. Other significant export destinations included China ($81.2 million), the Philippines ($60.2 million), and Australia ($27.2 million).

In Central Java, Banjarnegara stands out as the largest potato-producing region. Nationally, Central Java is the second-largest potato producer after East Java. In 2023, the total production in Banjarnegara reached 84,059 tons. With an average price of US$0.65 per kilogram, the economic value of this harvest amounted to approximately $54.7 million.

However, in 2023, Central Java experienced a decline in potato production. This downward trend is evident in Banjarnegara, particularly in the Batur District, which is the leading potato-producing area in the regency.

Yeyen Abadi Susanto, a 49-year-old potato farmer in Bakal, in another village in Batur District, highlighted the dire situation farmers face as they seek nearby water sources to irrigate their crops.

“We’re competing with a company that can pump water more extensively and quickly. If we don’t farm or fail to harvest, we can’t eat, our children can’t go to school. The losses are much greater for the local people,” he said.

Yati, a potato warehouse owner in Pawuhan, said that potato prices are currently surging by 50% compared to last year, due to lowering supplies. Large potatoes now cost up to $1.17 per kilogram, while medium-sized ones are priced around $1 per kilogram.

“Well, the prices are good and high. But, it’s because production is so low,” Yati said.

This year, she has experienced two failed harvests. She said strong winds in the dry season also add to productivity problems apart from water supply. Typically, she would harvest three to four times a year, with each harvest yielding 4-5 tons of potatoes.

“The last time we harvested, we only got half a ton,” she added.

Potato plants require ample and consistent water for optimal growth. During the flowering stage, watering may be necessary for up to 14 hours a day.

Mudofi, another potato farmer in Dieng, noted that the dry season is usually the best time for harvesting due to fewer pests compared to the rainy season. “However, even now, during the dry season, we face issues with wind and reduced water,” he said.

Farmers typically water their crops using a “3-1” method during the dry season, meaning three times in four days, Mudofi explains. Pesticide and fungicide applications during this season are generally done 6-8 times over four months or one harvest period. This number can increase two to three times during the rainy season due to greater susceptibility to mold and pests.

“Actually, pesticide use is lower in the dry season, but water availability is crucial; we must avoid drought,” Mudofi said, adding that he hasn’t calculated the exact water needs per hectare.

Mudofi has a 4-meter deep well behind his house to help irrigate his fields and meet household needs. Similarly, Yati has a 3-meter deep well at her home for irrigation purposes, though not for drinking. Like many in Pawuhan, she also draws water from Mount Prau for consumption.

***

To date, no specific studies have been conducted into whether there is a direct link between water and air pollution from geothermal activities and agricultural production in Dieng. However, a 2018 study done by scientists at the University of Arkansas found a connection between airborne and waterborne H₂S exposure and the health of rice plants. The study concluded that rice plants contaminated with H₂S exhibit complex nutritional deficiencies.

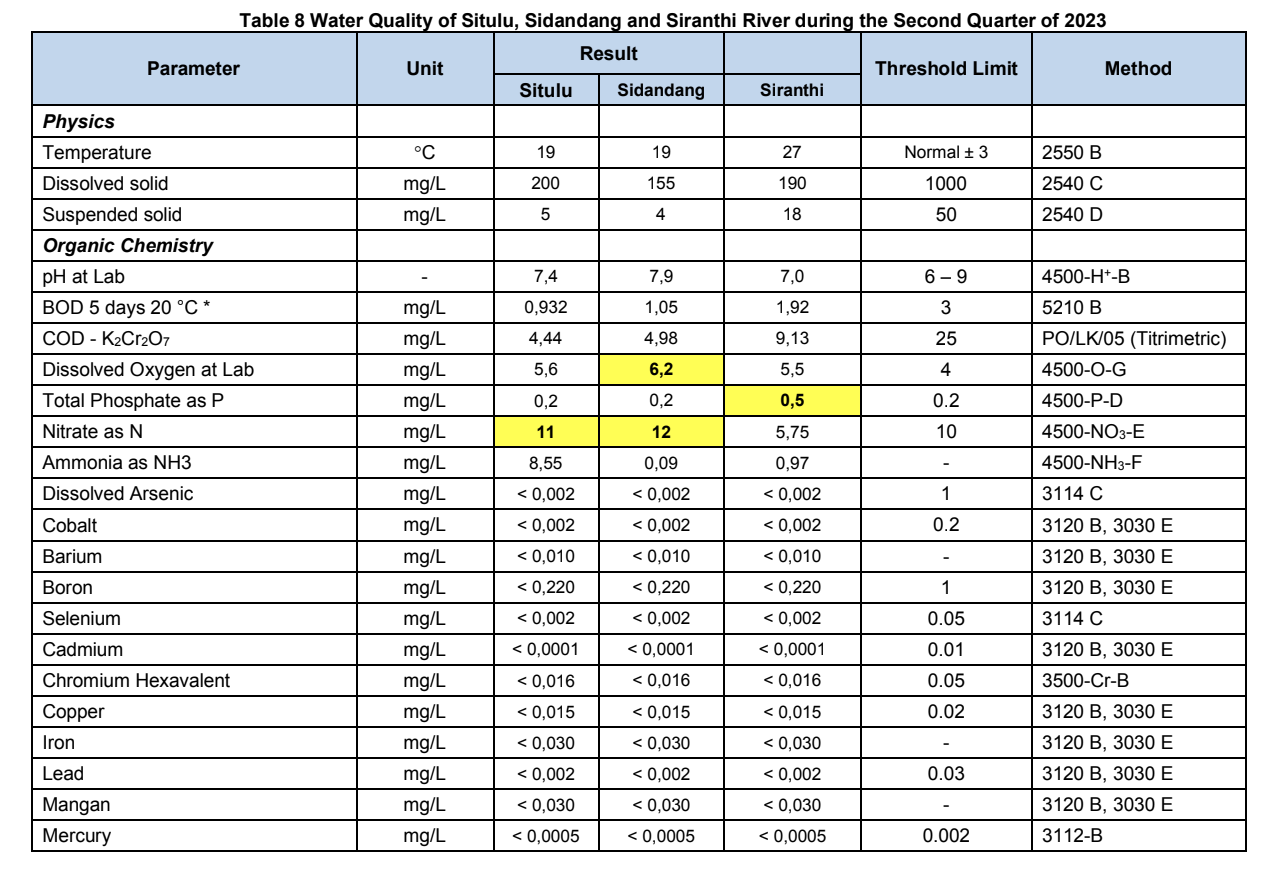

In a water quality test conducted by Geo Dipa in the first half of 2023, it was found that dissolved oxygen, nitrate, and phosphate levels in three rivers around the well and Dieng geothermal plant–Situlu, Sidandang, and Siranthi–exceeded permissible limits. The results were similar with the previous quarter monitoring.

However, the report stated “the utilization of fertilizers by the local farmers might affect water quality in the rivers.”

David Montgomery, a geomorphologist at the University of Washington, noted that while conventional agriculture can cause pollution through excessive use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers and pesticides, geothermal fluids containing heavy metals present a more severe challenge due to the difficulty of remediation.

“The water they’re circulating, [it] could have picked up [contaminants] from the geothermal system, that could be a far worse contaminant than the fertilizers,” said Dr. Montgomery.

Montgomery emphasized that contaminated soil has the ability to regenerate either naturally or with human intervention, but that this process can take a very long time. In his research, he found that globally, it takes less than 20 years to erode an inch of topsoil on average. While this may seem gradual, 1,000 years is required for an inch of topsoil to form naturally.

For heavy metal contamination, he added, one of the solutions to help recover the soil is by phytoremediation or using microbes or fungi. “The way to get rid of it is to actually grow plants that pull those heavy metals out, and then, you treat those plants as toxic waste,” said Montgomery, while adding, “but that’s expensive and hard to do.”

Serving Geo Dipa with Pawuhan water

Geo Dipa’s expansion plans for the Dieng 2 geothermal power plant sparked intense opposition from the local community. The proposed site for Dieng 2, covering six hectares of land owned by PLN, is situated right next to Karangtengah village.

In 2022, Geo Dipa began leveling the land just two meters from residents’ homes. Afterward, the company built concrete walls and fencing around the area.

Habib said Geo Dipa representatives initially told residents that the land would be used for employee dormitories and a health facility. It wasn’t until later that locals found out the site would house a new power plant.

“That’s when people started protesting. We drove the heavy machinery off the site every time they tried to bring it in. It happened repeatedly. Whenever they began working, we would stage a protest. Until there was a meeting with Geo Dipa directors,” said Habib.

Residents demanded the power plant be moved further from their homes, citing lingering trauma from past gas leaks and explosions, and fearing the geothermal activities would damage their farmland.

Habib stressed that the community wasn’t against development. When Geo Dipa announced the plan for dormitories, locals welcomed the initiative, recognizing that having Geo Dipa officers nearby could lead to faster and more effective response to any future incidents, thereby enhancing safety and support for the community.

In a 2022 pipeline explosion near Karangtengah, some residents rushed to Geo Dipa’s office in Pawuhan to demand accountability, only to find the building was empty–despite the explosion occurring on a working day at around 10 a.m.

“We were open to the idea of employees living here,” Habib said dryly. “Let them breathe the same air, drink the same water as the villagers.”

During a mediation meeting over the expansion with Geo Dipa, residents also served the directors water drawn directly from Pawuhan.

“We boiled it, prepared it in a thermos, and asked them to drink it. They just took the thermos–probably threw the water out along the way,” Habib said, adding that until now, the company hasn’t carried out any activities on the vacant land.

For its expansion project, Geo Dipa has secured a US$300 million loan from Japan’s Asian Development Bank (ADB). This also included a $35 million loan from the Clean Technology Fund (CTF), a World Bank initiative to finance environmentally-friendly projects in developing countries.

Hanif Osman, Chief Financial Officer of Geo Dipa, said that the construction of the Dieng 2 will resume in mid-2025. The delay, he explained, was due to regulations on the domestic content requirement (TKDN), which mandates that 34% of the infrastructure be locally sourced.

In July 2024, former Energy Minister Arifin Tasrif signed Ministerial Regulation No. 11/2024, easing the TKDN requirement for renewable energy projects. This change effectively removes the TKDN stipulation for companies like Geo Dipa, which secure financing through development finance institutions (DFIs).

Addressing community protests over the expansion plan, Hanif claimed the issue had been resolved. “The protests were primarily about how close the project was to residential. We will relocate the project slightly further, though it will still remain within the same area,” Hanif said during an interview in Jakarta in September.

Hanif emphasized that the new location complies with regulations, specifically referring to Presidential Regulation No. 21/2014, signed by former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

“Technically, there are no issues–it’s safe,” he added, stating that the site had been reviewed with environmental considerations in mind. “Everything has been carefully calculated, both in terms of cost and environmental impact.”

The Dieng 2 plant is expected to be completed and operational by 2027. “There will be 10 wells for Dieng 2…and once that’s done, we’ll move on to constructing Dieng 3 & 4,” Hanif concluded.

Silent fears, unheard concerns

Hariyati, a farmer from Pawuhan, didn’t say much when asked about her hopes for the future. “Me? As long as my kids can finish school and stay healthy, I think that’s enough.”

She doesn’t know much about the expansion plans but imagines the noise will be more frequent once the plant becomes fully operational. Pawuhan is just four kilometers, or about a nine-minute drive, from Karangtengah.

“The noise from Geo Dipa is really loud. You can often hear the rumbling, and if they add more, it’ll only get worse,” she said.

Yet, she doesn’t have courage to join the opposition, though she knows many Pawuhan residents regularly protest the company over various issues. “I don’t want to get involved,” Hariyati said. “I’m just a nobody. If I get targeted, I could lose everything.”

Bhima Yudhistira Adhinegara, director of CELIOS (Center of Economic and Law Studies), a think-tank based in Yogyakarta, warned that the greatest losses from the environmental impacts of geothermal will ultimately fall on local communities. The long-term risks, including pollution and water supplies, will weigh heavily on the local economy.

“Money that should go toward food and education will have to be set aside, one of them is for healthcare costs,” Bhima explained. “And most importantly, these geothermal projects don’t even benefit nearby communities in terms of electricity, especially considering Java’s current oversupply.”

Since 2013, the Java-Bali grid has been experiencing a surplus of electricity, largely driven by coal-fired power plants. PLN, the country’s only player in electricity distribution, has struggled to manage this excess supply efficiently and at affordable prices.

Amid this situation, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo launched the 35 GW power capacity addition program in 2015, pushing forward large-scale power plant projects throughout the nation, including in Java. Many of these projects, however, still rely on dirty energy sources.

By 2023, the electricity surplus in Java had reached 44%, or about 4 GW. For every 1 GW of unused electricity, PLN is estimated to lose around US$200 million. However, as a state-owned enterprise, PLN’s losses are ultimately covered by the government through capital injections.

“This, in turn, drains the state’s fiscal capacity, funds that could otherwise be used to improve public welfare,” said Bhima.

Agung Rizal Setiawan, a young man from Bakal village, located less than 3 kilometers from Karangtengah, said that the biggest threat from expansion is the loss of vital water springs that sustain the community.

Rizal, who is currently a graduate student in agriculture at Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta, pointed out that even without expansion, the residents have complained a lot about water and other problems.

“In Dieng, all geothermal activities are too close to people. Some are near tourist sites, some run right in front of homes. There’s no boundary between people and the plant anymore. The longer this goes unchecked, the more inhumane it becomes,” Rizal said.

He demanded the company to take responsibility for the environmental damage in Dieng. He also challenged the company to prove, in front of the community, how it plans to repair the damage that it has caused.

“In South Korea, geothermal energy is being phased out. Imagine that, a country with more advanced technology is moving away from it. Here, we’re still experimenting, and the community is the guinea pig,” he remarked.

*Hariyati and Aziz are not real names; a pseudonym is used to protect her identity out of fear of retaliation.

This article is part of Earth Journalism Networks’ Ground Truths collaborative reporting project on soils in the Asia Pacific.