The conventional wisdom is that Indonesia is suffering a democratic decline because of the authoritarian tendencies of its leaders and the illiberalism of its people. To quote Australian political scientist Marcus Mietzner, outgoing President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo “pushed the limits of democratic norms and even overstepped them”, and the people have been fine with that.

This view represents the common thinking among progressives within Indonesia’s political class. Muslim scholar Sukidi’s recent commentary in Tempo magazine, for example, satirized Jokowi as Pinokio Jawa, or Javanese Pinokio. Long before that, The Jakarta Post, Indonesia’s largest English daily, had dubbed Jokowi “little Soeharto”, a reference to the New Order autocrat who ruled over Indonesia between 1967 and 1998.

That thinking is not totally groundless. Jokowi has been accused of weaponizing law enforcement institutions to intimidate his political enemies, co-opting judicial institutions to build his political dynasty, and mobilizing state resources to guarantee the victory of his children in regional and national elections. He is also believed to have recently orchestrated a plot to prevent the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) and former presidential candidate Anies Baswedan from contesting the Jakarta gubernatorial election – a race both figures have previously won. Such a power play would clearly be aimed at ensuring that Jokowi’s alliance with his former election rival, Prabowo Subianto, would go unchallenged for years to come.

The problem is that this view tends to frame Jokowi as the sole architect of our political malady, and implies that removing him would be a sufficient remedy. That’s just lazy analysis. The reality is that his rise to power was enabled by different social forces, who have capitalized on his presidency to further their political and economic interests. His enablers, alas, are not confined to a group of coal industry oligarchs who spent billions of rupiah to finance his election campaigns and were later given strategic positions in the Cabinet to create public policies that serve their private interests.

It is high time to acknowledge the elephant in the room: many Indonesian intellectuals are complicit in decimating Indonesian democracy. I define intellectuals broadly to include academics, journalists, activists and religious leaders. Many of these figures have turned a blind eye to, if not directly abetted, Jokowi’s illiberal policies under the pretext of defending pluralism — a crusade against Islamism — and championing technocratism.

A pluralist, technocratic leader

Truth be told, Jokowi was always the favorite of Indonesian intellectuals. This is not only because he was seen, at least initially, as a political outsider with no links to the New Order’s oligarchy, but because he accommodated the dominant ideologies of the urban, educated middle class, particularly those claiming to be defenders of Indonesian pluralism.

It is worth noting that those critical of Jokowi today were in fact once his ardent supporters. At best, their criticisms of Jokowi are too late and too little, as exemplified by the joint statements issued by university professors just a few weeks before the February presidential and legislative elections, sparking speculation they were acting at the behest of Jokowi’s oligarchic rivals. Whatever the case, their criticism smacks of hypocrisy. Many Indonesian intellectuals in fact knew Jokowi had authoritarian tendencies, but they looked the other way when his illiberal policies worked in their favor. They were not only silent but also actively supported Jokowi’s illiberal policies towards Islamist groups.

This was visible during Jokowi’s first term in office, when he was facing an Islamist opposition empowered by his oligarchic rivals. The period was marked not only by the incarceration of then Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama for blasphemy, but also the arrests of dozens of political dissidents on dubious and politically motivated charges, ranging from pornography to treason. Jokowi’s illiberalism culminated with the banning of two Islamic groups — Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) and the Islam Defenders Front (FPI) — and the alleged extra-judicial killing of FPI members.

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah are two key organizations underpinning Jokowi’s illiberal pluralism. While these large Muslim groups are not monolithic, their elite members are overwhelmingly supportive of the President. There is no doubt that both organizations have long served as a bastion of religious moderation in the country, but the implication of their Faustian bargain with Jokowi is clear: their whole campaign against religious intolerance to protect minority groups and preserve diversity was more often than not just a ruse to justify his illiberal policies, which in fact were created mainly to protect the political and economic interests of the oligarchy.

Many Indonesian intellectuals were also supportive of Jokowi’s legislative initiatives that critics said had illiberal tendencies, such as the 2020 Jobs Creation Law. The campaign supporting the controversial law was backed not only by paid cybertroopers, but also academics, including political researchers, who framed it as a technocratic remedy to the COVID-19 economic crisis and a technocratic recipe for turning Indonesia into a developed country.

They defended the law even after it was clear that it was passed without meaningful public consultation, and that it contained illiberal provisions. Regardless of whether they were paid to express their support for the highly problematic law, this shows how the very notion of technocratic leadership could easily be co-opted to disregard democratic norms.

Jokowi’s ‘sorcerers’

Jokowi is a product of the political consultancy industry that boomed during the 2012 Jakarta election. Throughout his presidency, he has relied on political and PR consultants to engineer his persona as a “technocratic populist”. He regularly hired several polling agencies who provided him with statistical data that he could use to not only calibrate his policies, but also to justify his illiberalism. This was most apparent when pollsters suddenly released political surveys that challenged unflattering narratives about his policies on social media.

They are the “sorcerers” who enabled Jokowi’s autocratic machinations.

Several pollsters, such as Indo Barometer and Cyrus Network, have openly expressed their partisanship, if not business dealings, with the President. It is likely that the President, or at least his close allies, have hired many other pollsters too. It is no secret that pollsters who are commissioned to conduct surveys (usually by political parties/politicians) are motivated by profit; this is money they can then use to fund their own surveys. The problem is that they are not always transparent about which surveys were paid for by the powers that be, even if it is clear the survey results serve the interests of the powerful.

It is clear, however, that surveys which have found that Jokowi was highly popular and the public were mostly supportive of, or at least nonchalant about, his authoritarian tendencies have been used to justify unconstitutional proposals, such as extending his term, and normalize his cawe-cawe (meddling) in the judicial system and the internal affairs of political parties.

The pollsters should have known that poll results shape public opinions. It is baffling, for instance, that a high-profile pollster like Indikator Politik Indonesia decided to release opinion polls claiming that the majority of Indonesians were fine with the Constitutional Court’s ruling to pave the way for Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, to run for vice president alongside Prabowo. This polling was released when it was clear the ruling was flawed on so many levels, and that there was, for a moment, a certain level of public pushback against it.

The survey results practically shut down any discussion about the ruling, as it portrayed those critical of the court’s ruling — the more progressive intellectuals — as detached and elitist.

Intellectuals of the oligarchy?

In the grand scheme of things, the Jokowi phenomenon is nothing but a symptom of a long-standing asymmetric power structure within Indonesian civil society in which a weak middle class, from which most intellectuals originate, is too dependent on the oligarchic elite to advance their own progressive visions. The result is a reproduction of a system of power where the politically and economically powerful have co-opted public intellectuals to sustain and even strengthen their power.

It is no surprise that after defending the NU’s decision to accept coal mining concessions from the Jokowi government, Muslim scholar Ulil Abshar Abdalla posted a long social media screed downplaying concerns about democratic regression under Jokowi. In a clear attack on the idea of democracy as defined by “foreign observers”, he said that what Indonesia needed was “political order” to achieve prosperity, and not political bickering among political parties.

And that is how democracy dies in Indonesia, not with a bang but with the sophistry of a group of intellectuals too weak to countervail the power of the oligarchy.

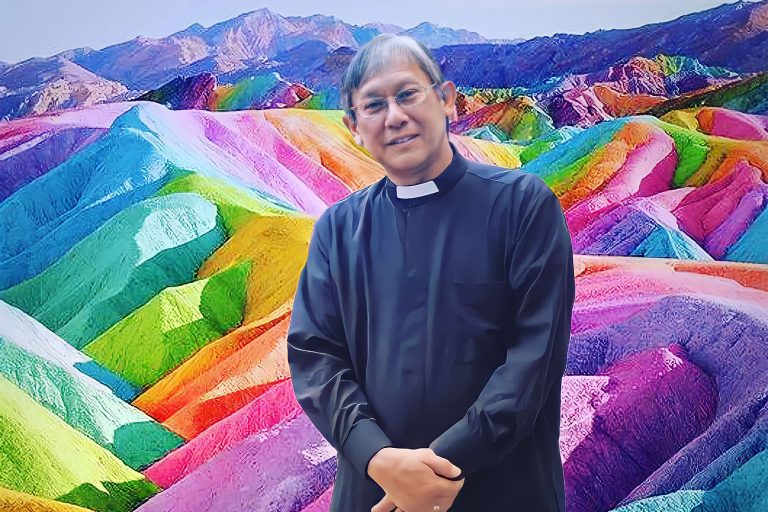

Ary Hermawan

Co-founder of Project Multatuli, PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne’s Asia Institute and editor of Indonesia at Melbourne