Bali’s indigenous Dalem Tamblingan people have called Lake Tamblingan and the Mertajati Forest home since at least the 10th century. But the Indonesian government’s decision to designate the area a tourist destination has robbed them of the land they hold sacred.

Thick fog blurred Wayan Suci’s vision as she rowed her canoe on Lake Tamblingan. She was taking two visitors to enjoy the charms of the 1,847-hectare Mertajati Forest (also known as Mertasari Forest), located in the Balinese regencies of Buleleng and Tabanan.

Birds were chirping as the soft pitter-patter of the rain transformed into a storm. Stuck in the middle of the lake, Suci’s guests panicked, worried they wouldn’t be able to get back to shore.

It has been nine years since Suci, 61, became a menega, a revered guardian of Tamblingan Lake, a highly respected role that dates back to the 14th century. Taking visitors out onto the sacred lake is one of her many responsibilities.

Normally, only male descendants of Abdi Panjak Wancing, an ancient figure referred to in the Balinese Babad Hindu Gobed Gobleg chronicle, occupy the role. But when her husband, himself a menega, died in 2015, Suci took up the mantle, reluctantly at times.

“I was devastated that day. My husband left home perfectly healthy but came back lifeless. There were no words to describe my feelings,” she says.

When she was named the new menega, Suci did not know how to swim or row a canoe.

“I wasn’t sure if I could do the job. I didn’t want to put anyone in danger. Thankfully, I got help from other menega,” she adds.

Her fear of the lake was nothing compared to the destruction of the environment surrounding it.

Things took a turn for the worse when the Environment and Forestry Ministry designated Mertajati Forest a natural tourism park in 1996. After protecting the area for generations, members of the Dalem Tamblingan indigenous community suddenly found themselves unable to enter the forest freely. Everyone but menega was obligated to buy a visitor ticket to enter the area, according to government rules.

A History of Destruction

Another traditional role, that of the nyapuh, exists to watch over Mertajati Forest. This role is reserved for descendants of Tegeh Kori, another ancient figure chronicled in the lontar Babad Hindu Gobed Gobleg.

Mertajati Forest’s story of destruction began when the Dutch colonial government named it a tourist destination in 1927. Seven years later, it became part of the Batoekaoe Natural Reserve in recognition of its importance to the watershed.

Under Dutch rule, the people of Tamblingan were forced to grow coffee in the forest area. Later, the Indonesian government required the local community to switch to growing cloves, garlic, vanilla, and cocoa.

According to Ketut San, 37, secretary of the youth organization Baga Raksa Alas Mertajati (Brasti), continuous land use change has diminished the water level of Lake Tamblingan. And reliance on chemical products for agriculture in the area has made matters worse.

Brasti’s work spans conservation, education, economics, and data, and its members are vocal about local environmental issues.

“The vegetables grown here come from genetically modified seeds that were sold to us by the government. As the forest’s watershed capability diminished, we began to experience landslides. But there is nothing we can do,” says Ketut San.

The same could be said of Lake Tamblingan. When the local administration of Buleleng opened the lake to the wider public for fishing in the 1980s, temporary settlements began to line the lake’s shores. Their expansion degraded the area over the following years.

The settlements were cleared and the inhabitants relocated in 2015, following discussions with the local community, but the damage was done. The introduction of invasive species into the habitat led to the extinction of the lake’s native nyalian (Barbodes binotatus Valenciennes) and kuyuh (taxonomy unknown) fish.

Kadek Adi Rismawan, another menega, says the extinction of the endemic fish species had a negative impact on the indigenous community’s long-held tradition of banten, which involves the preparation of a sacred offering containing the fish.

The government-sanctioned Natural Resources Conservation Agency (BKSDA) regulates fishing in the lake, a task previously performed by the menega.

“The conservation agency continues to issue new fishing permits. These fishers come from Karangasem, Ubud, and only a few are indigenous Tamblingan people,” said Rismawan.

To conserve fish populations in the lake, the menega once managed fishing through traditional sipeng law. But those time-honored rules have gone unenforced since the government took over.

“There is not much we can do as menega today. Government officials are in charge of the lake. I do not even patrol anymore. [Before this] nobody could install fishing nets without my permission,” says Suci.

The indigenous community is powerless before the government. Their lontar chronicles, which establish their indigenous rights to the sacred lake and forest areas, are not legally recognized by the government.

“It is ironic how the government comes to us whenever there is a problem but does not recognize our local wisdom, or dresta kuna,” says Ketut Artina.

***

The existence of the indigenous Dalem Tamblingan people and their traditional way of life is well documented in the Tamblingan Pura Endek inscription, which dates back to year 844 in the Shaka calendar (sometime in the 10th century). It tells the history of the Anak Banwa Tamblingan community and is one of 10 inscriptions used to justify the historical claims of the indigenous community of Tamblingan Lake and the Mertajati Forest.

Other inscriptions, such as Gobleg Pura Batur B and Tamblingan Pura Endek IV, contain traditional laws limiting logging and hunting in the area, suggesting that the indigenous people were practicing conservation long before the Indonesian government took over.

The conversion of Mertajati Forest into a natural tourism park has prevented new generations of Dalem Tamblingan people from preserving their ancestors’ connection with the sacred lake and forest.

“Many of us in the younger generation have been robbed of our rights. We will be arrested if we enter the forest without an entry permit,” says Ketut San.

Robbed of Rights

The government conservation agency divides the national tourism park into conservation, tourism, religious, extraction, and special blocks. Despite the park’s overarching designation as a conservation area, the government grants permits to private corporations to extract resources from Tamblingan, which Sumarsono says are limited to within the extraction block.

“The special block houses vital objects such as electrical grid [infrastructure] and power plants. The law allows us to be flexible in accommodating non-conservation needs,” says Sumarsono of Bali’s conservation agency.

The agency claims that the designation of Alas Mertajati as a natural tourism park follows a precedent set by the Dutch colonial government.

“When the Dutch designated the forest as a conservation area, it was done in an agreement with Balinese traditional rulers,” says Sumarsono.

Long before the arrival of the Dutch, the indigenous Tamblingan people had established Mertajati Forest as a conservation area. This is documented in the Buyan Sanding Tamblingan inscription, which records traditional rules limiting the quantity of plants and animals that could be taken from the forest as well as regulating irrigation in the area to sustain agriculture.

The government’s conservation approach is not consistent with the guidelines set by the Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), which defines conservation as efforts to maintain essential ecological processes and life-support systems, preserve genetic diversity, and ensure the sustainable utilization of species and ecosystems.

Sumarsono says the government’s approach is to use conservation areas for other purposes as well.

“Our conservation policy must benefit the people. It can’t be just for the sake of conservation itself, especially when we rely on the resources to ensure public welfare,” he says.

***

Illegal logging presents another challenge to the forest. In 2015, residents conducted night patrols to fend off illegal loggers. The local police helped the community patrol the forest chief access points.

“During one of our patrols, we caught four people with a truck full of logs. Two of them were civilians and the other two were BKSDA officials. I am not accusing the conservation agency of being thieves, but that is simply what happened,” says Putu Ardana, a Tamblingan elder.

“[The Buleleng administration] wanted to find a middle ground, but we insisted on pursuing legal action. Eventually, it went nowhere and the district police chief who assisted us was relocated elsewhere,” he adds.

Many in the indigenous Tamblingan community are disappointed with the lenient attitude and opaque legal processes.

“It says a lot that instead of the conservation agency, the community sought help from the police to patrol the forest,” says Ketut Artina.

Indigenous People and Development

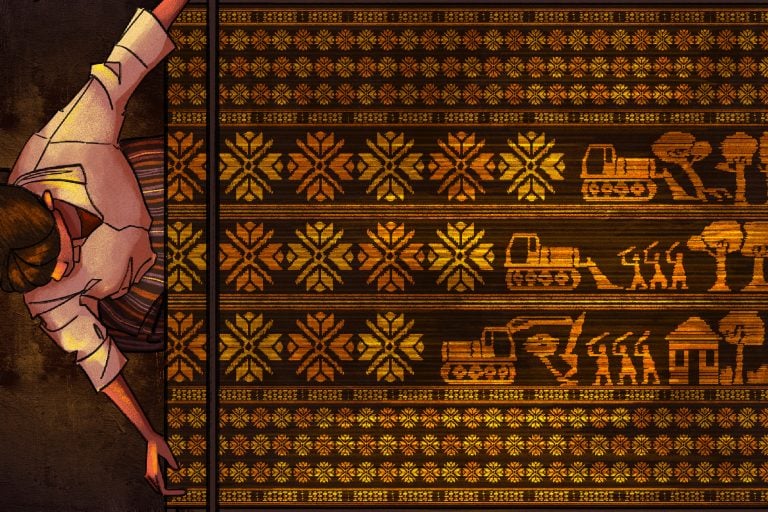

Amid relentless development led by private corporations, the land of Mertajati Forest has been slowly turned into a commercial area.

“As indigenous people, we are constantly bombarded with all sorts of investment projects, from cable cars [passing] above our temples [in 1999] to floating restaurants and villas,” says Putu Ardana.

I Gusti Ngurah Agung Pradnyan, a pengrajeg (indigenous leader), says the community’s rejection of development project proposals is rooted in concerns that the undertakings will harm the natural environment of the forest.

“If the project had continued and harmed the forest, we would only have ourselves to blame if wild animals began to invade residential areas,” he says.

In 2016, the community rejected a proposal by PT Nusa Bali Abadi to develop an amusement park in the area. The local administration responded with frustration.

“We expressed our opposition at a meeting with government officials, including the director-general and regent Bagiada, which angered them,” says Ketut Artina.

Artina still remembers the words uttered by the regent.

“You are saying no to a lot of money,” he recalls the regent saying. “I went to Beijing to get investors to commit and you just rejected it.”

Despite promises of economic benefits, the indigenous people are adamant in their position.

“Investors tried to convince us to convert the forest. They said it would create jobs and bring a steady source of income. But it was ridiculous. Without the forest, our agriculture will fail,” says Agung Pradnyan.

The Dalem Tamblingan people used to be part of a single village. But the Dutch colonial government divided their village into four. Post-independence, the Indonesian government further divided their community into more administrative divisions.

In 2008, the High Council of Pakraman village issued a decree permitting development projects there. The indigenous community, including those of the four main villages of Munduk, Gobleg, Gesing, and Umajero, were never consulted and rejected the decree. They felt that the projects would push their rich history and tradition closer to extinction.

Their rejection put a stop to the plan.

Elders of the four main villages formed a task force to jointly address the threats to their land and traditions. When tourism development company PT Sekarmas Nusantara proposed a plan to build a natural resort in the forest area, they had the backing of a letter from the director-general of natural resources and ecosystem conservation at the Environment and Forestry Ministry.

The task force established Baga Raksa Alas Mertajati (Brasti) in October 2020 to ensure that younger generations of the indigenous group could join in the fight.

“We are facing modern challenges rooted in unfettered capitalism. We hope Brasti helps our younger generation fight those threats,” says Putu Ardana, who leads the task force.

***

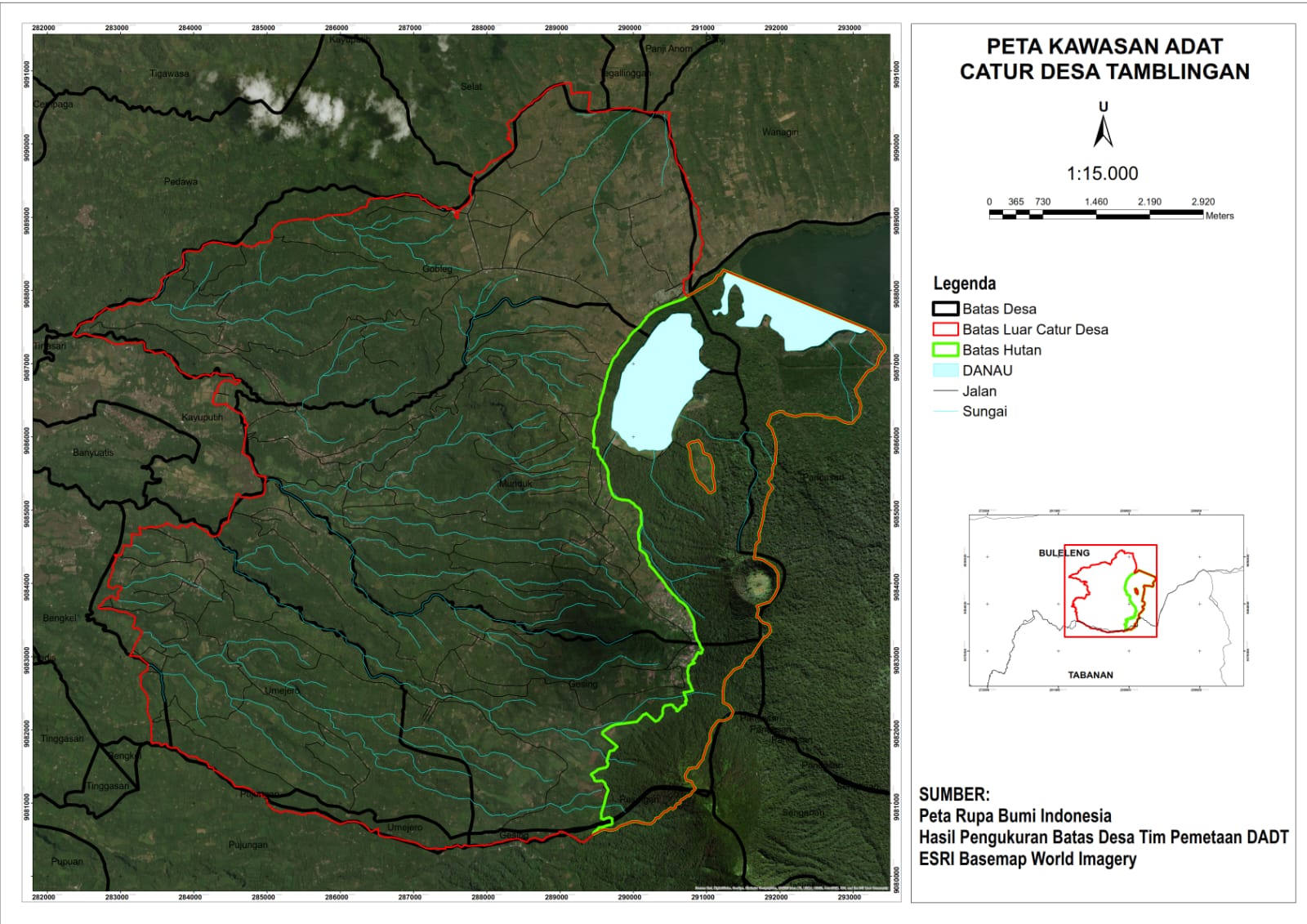

Brasti has coordinated efforts by the younger generation of the Tamblingan people to properly map the Mertajati Forest area by surveying territorial borders, social and economic conditions, plants and animals, the watershed and temples in the area.

“I was ignorant before I joined the survey project. I did not know anything about the forest and the lake. It is so important for the younger members of our indigenous community to be connected to the land. We would not have known that the watersheds were drying up if it was not for the survey,” says Komang Werdiasa, 42.

Komang and his team found evidence of illegal logging in Mertajati Forest during the survey. They believe the watershed as a whole is being affected by such deforestation.

“Endemic trees such as Cemara Pandak, Kwanitan, and Sotan Busung are now hard to find because illegal logging continues,” he says.

To understand the history of their land, younger members of the Tamblingan people closely consulted their elders throughout the survey. They hope their efforts will help restore their indigenous rights to Mertajati Forest despite the lack of government support.

“We submitted our spatial map to the Buleleng regent in 2019. It has been four years, and they haven’t approved it. Without the map, we can’t do anything,” says Putu Ardana.

They have also sought legal recognition from the Environment and Forestry Ministry and the House of Representatives. But neither effort has borne fruit.

“We have already waited 1,000 years to get our rights. What’s another 500 years? All we have is patience, strength, and conviction,” says Putu Ardana.

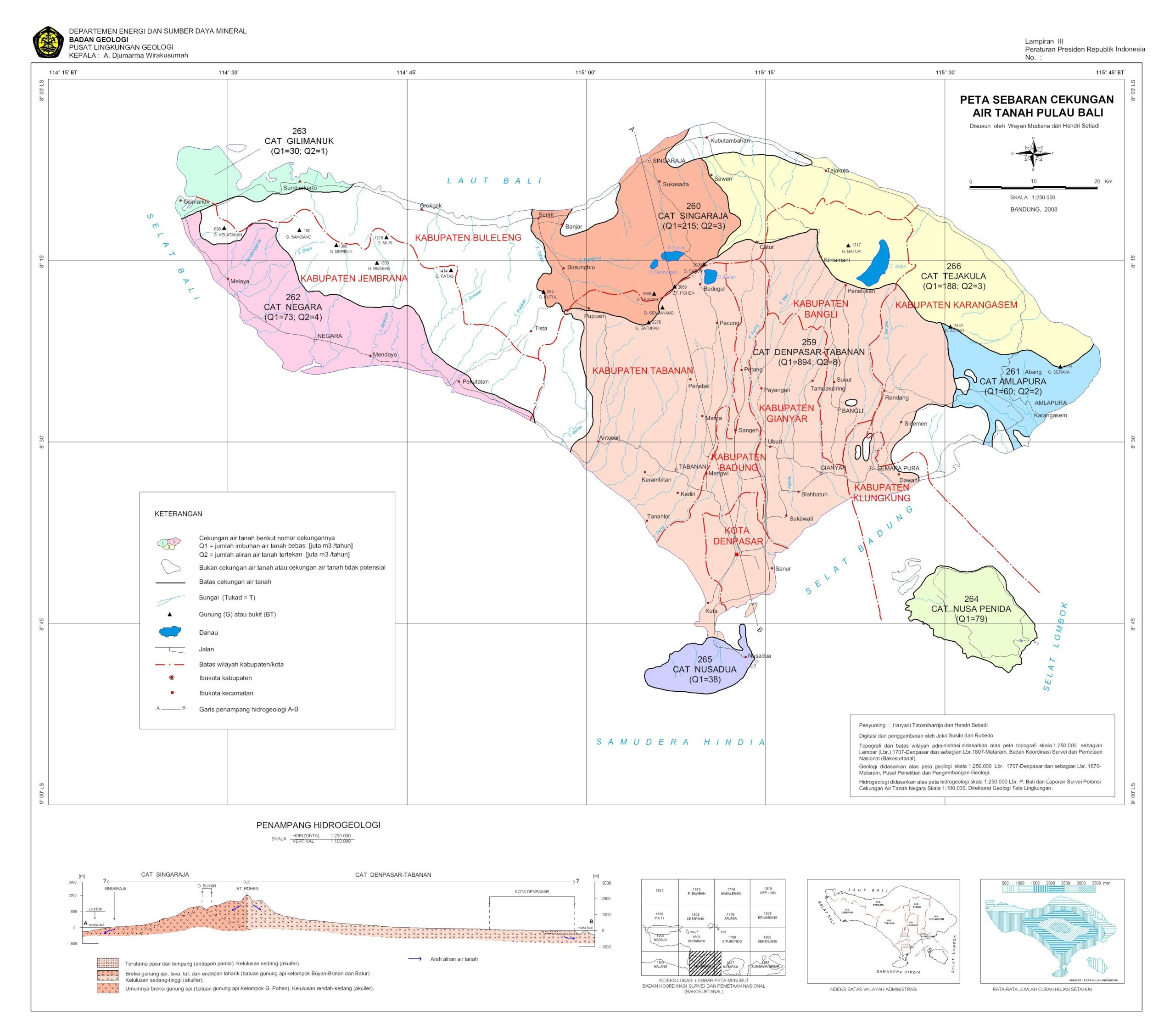

But the fight for Alas Mertajati is not just for the Dalem Tamblingan people. For centuries, the area has supplied groundwater basins that cover other areas in Bali, from Singaraja to the Denpasar-Tabanan area.

Maintaining a harmonious relationship with nature is a central value in Balinese indigenous beliefs. And water plays a key part in traditional rituals.

The conservation of Mertajati Forest is also crucial to fighting the climate crisis. Its loss may bring more extreme meteorological events to Bali, such as drought, cyclones, heat waves, floods, and landslides.

The importance of Mertajati Forest to sustaining life in Bali is recognized by those outside the indigenous Dalem Tamblingan community, including researchers, activists, international organizations, and other indigenous groups who benefit from the water provided by forest.

“In 2022, we participated in the Asia Parks Congress in Malaysia, which exposed our plight to the international community,” says Ketut San.

Water and Mertajati Forest

Water is crucial to the way of life of the Dalem Tamblingan people, not only for their agriculture, but also for their spiritual practices.

The indigenous community’s Piagem Gama Tirta belief calls on them to live in harmony with the natural environment and water resources and to hold Tamblingan Lake and Mertajati Forest as sacred. For centuries, this belief has helped ensure reliable water access for people in one third of the island.

The three-month-long indigenous Lilitan Karya ritual reflects the relationships between the Tamblingan people and other communities in Singaraja and Tabanan who benefit from the forest watersheds.

In it, participants walk a 22 kilometer path upstream to Segara Labuan Aji beach in Banjar, Buleleng. The villagers along their path treat them to meals as an expression of gratitude.

“They are thankful for the life-sustaining resources that Mertajati Forest provides to them. Lilitan Karya symbolizes the way that we build our community and conserve water,” says Putu Ardana.

A folk tale tells of a love between a couple, one of whom lived upstream of Lake Tamblingan and one of whom lived downstream. It has been a central cultural element for generations of Tamblingan people. Over 250 families in Banjar Lebah make a living from 123.7 hectares of rice fields in Subak Panataran that are irrigated by Lake Tamblingan.

Sudarsa, an elder of Subak Panataran, says his community relies on Lake Tamblingan to sustain its farms. He has also rejected development projects planned in the Mertajati Forest area.

“Even if nobody listens to us, we will continue to fight. If we don’t protect the forest, we will lose the water supply,” he says.

The conversion of Mertajati Forest for commercial purposes threatens the way of life of Bali’s indigenous people as a whole.

“We will die without Tamblingan. Seririt has no watershed, let alone Tabanan,” Suci, the menega, said, referring to neighboring places in Bali. “Where else will we find water?” she said.

She said the government should not have handed over the rights to the lake and forest to corporations. She hopes that the government will one day recognize the roles that indigenous people have in conserving the environment. Otherwise, the indigenous people will not have anything to bestow to the next generations.

“The lake is my source of life. I will die without the water. There will be nothing to eat. Tamblingan is medicine [for the world],” says Suci as she stares far into the depths of the lake before her.

This article is part of the #IndigenousPeople series.

Translated into English by Ravio Patra, a generous Kawan M or supporter of Project Multatuli. The piece was first published in Indonesian.