In a chaotic world of collectors, deforestation and climate change, the silent threat of butterfly extinction gives a quite literal meaning to the term “butterfly effect”.

The reporting for this story was made possible by a Pulitzer Center Rainforest Reporting Grant.

In 1859, after his ship burned down in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace traveled to Bacan Island in the Maluku Islands. There, he caught a golden-winged butterfly that he fell in love with. In his book The Malay Archipelago, he wrote:

“The beauty and brilliancy of this insect are indescribable, and none but a naturalist can understand the intense excitement I experienced when I at length captured it. On taking it out of my net and opening the glorious wings, my heart began to beat violently […]. I had a headache the rest of the day, so great was the excitement produced by what will appear to most people a very inadequate cause.”

The butterfly was named Wallace’s Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus). One of a dozen species in the genus Ornithoptera, or birdwing butterflies, it is the largest butterfly species in the world. It can only be found in the northern parts of Australasia, including Papua and the Malukus.

These butterflies soon became the object of desire of wealthy Europeans seeking to flaunt their status with collections of exotic animals in frames. Later, it was this same butterfly that helped Wallace develop the theory of evolution through natural selection more or less concurrently with Charles Darwin, establishing Wallace as the father of biogeography.

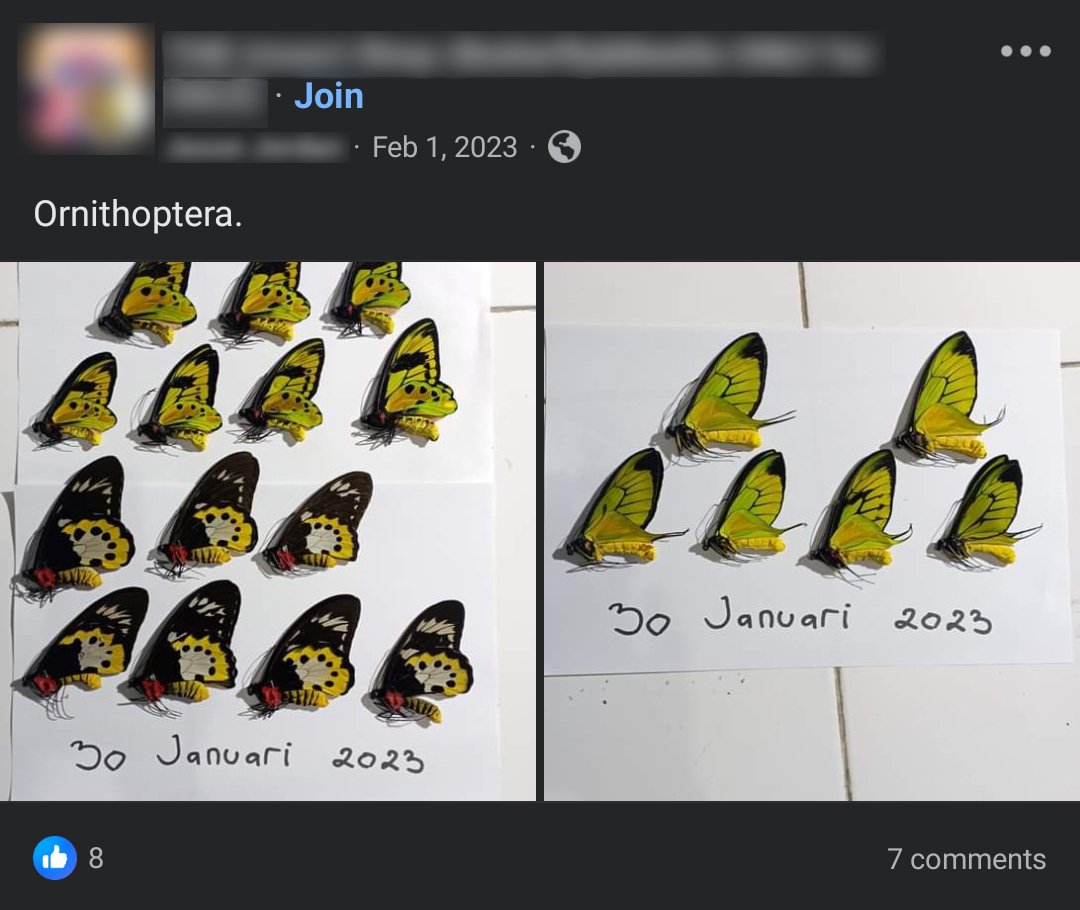

More than a century and a half after the publication of The Malay Archipelago, Ornithoptera species are still favorites of the world’s butterfly collectors. In fact, this longtime obsession is one of the reasons why the population of birdwing butterflies in Indonesia is decreasing. But it is not the only reason.

“If we came here during the rainy season, we wouldn’t be able to walk like this. We’d have to swim,” says Ongen as he holds my hand while I struggle to keep my balance in the middle of a river.

We have been walking for an hour to his butterfly farm, located in a forest on one of the islands of the Malukus. To get there, we rode a motorbike to a muddy sand quarry and proceeded onward by foot, fording the same winding river a dozen times. The further we got from the mining area, the clearer the water became and the denser the vegetation on the river’s banks.

Surrounded by coconut trees, we arrive at the breeding center, which turns out to be a simple house nestled between the river and a forested hill. It is a strategic location because the open forest edge and the nearby river create an ideal habitat for butterflies. Ixora flowers, pagoda flowers, bougainvillea, nusa indah, hibiscus, and a variety of other plants fill the yard, reminding me of my grandmother’s garden.

Among them, dozens of butterflies of various colors and sizes fly, apparently unconcerned by the four silk butterfly nets aligned on the terrace. On the southern side of the house sits the center’s treasure: a birdwing butterfly breeding cage almost the size of a futsal court.

“In the right season, the butterflies can be more tightly packed than this. Just sit around swinging the net, and you’ll get them,” Ongen says.

It is from this breeding ground that Ongen runs his butterfly trading business. He breeds and hunts exotic butterfly species from eastern Indonesia and supplies them to buyers around the world.

“Europe and Japan usually have the most demand, but recently I’ve been exporting to China. The butterfly hobby is trendy there,” he says. “One of the most sought-after collectors’ items is Ornithoptera priamus, which is expensive.”

Ornithoptera priamus, or the common green birdwing butterfly, is one of the 12 species of the coveted birdwing butterfly, called “birdwing” because of their large wingspan and bird-like flight. In Indonesia, all birdwing butterfly species are protected.

Ornithoptera priamus is one of the few invertebrates listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This means it can be traded, but only under certain conditions and with specific permits.

Ongen propagates the species at his captive breeding center. He has been running his business since 2021, after his father passed away. It was his father who introduced him to the world of butterflies as a child. Perhaps that is also what makes Ongen such a butterfly expert. He knows almost everything about them by heart.

“I used to accompany my father to hunt with butterfly collectors from Japan in the forest, I think since 1972,” he recalls.

Ongen has five employees at the breeding center. They catch female birdwing butterflies for broodstock, monitor the eggs, ensure the caterpillars are well fed, take care of the chrysalides and plants, and package the specimens, among many other tasks. With no cellular signal and no electricity, the hut feels like a hermitage. But the sounds of the river and forest animals are broken by the persistent roar of chainsaws from the encroaching mining operation.

“The noise of the chainsaws doesn’t stop, not even at night. It might only stop when the forest is gone,” Ongen says with bitterness in his voice.

He invites us into his butterfly cage, an 8-meter-high room with wire walls covered in transparent black netting. It feels more suited to an elephant than a collection of butterflies.

“In the forest, birdwings fly high up in the canopy of the trees. If the cage is short, they won’t be able to fly, poor things,” says Ongen.

In addition to the flowers, the enclosure is filled with the leaves of the forest betel (Aristolochia), the host plant of Ornithoptera priamus. In its natural habitat, Aristolochia can be found creeping up the trunks of large, woody trees in areas with plenty of sunlight. The plants are crucial in captive breeding, as Ornithoptera priamus caterpillars will eat only Aristolochia leaves.

As we walk in, we look upward and spot something flapping rapidly above: the butterfly in question. If I hadn’t been told beforehand, I would have thought it was a bird.

In one corner of the enclosure is a sterilized room measuring 2 by 2 meters. Inside are dozens of cocoons attached to three lengths of string. Most are Ornithoptera priamus cocoons developed from eggs laid in the cages. They were moved to the sterile room to give them a better chance of hatching.

Ale, an employee of Ongen’s who takes care of the cocoons, says, “It takes one week to go from egg to baby caterpillar, five to six weeks from baby caterpillar to adult caterpillar. Then, it becomes a cocoon for 40 days. Then, it hatches. If there are no predators, it can live up to three months.”

“Only three months?” I ask.

“That’s already a long life for a butterfly.”

*

That morning, I had been watching a chrysalis that had turned blackish, a sign it was about to hatch. After a short time, I saw the butterfly crawl out and hang on the outside of the cocoon. A newly hatched butterfly can’t fly immediately. It has to unfold its wings and wait a few hours for them to dry.

Later, the same butterfly took flight and landed on my hand.

I held my breath and tried not to move. It was my first time holding a live male Ornithoptera priamus in my hands. Up close, its dashing velvet wings and green-black hue looked strikingly regal. Its cream-colored tufted feathers, yellow abdomen, red vest-like thorax, and new proboscis added to the effect. Perhaps it was adjusting to its new body, I thought.

I was mesmerized by the perfectly arranged colors and symmetrical patterns. It looked like a fresh blossom. For a moment, it almost made sense that some people were willing to pay large sums of money to have it in a glass box in their homes.

A moment later, with a quick motion, Ale scooped it up with two hands and pinched its thorax with two fingers.

“You have to squeeze it immediately, while the wings are still good. If the wings are damaged, it can’t be sold,” Ale said.

The butterfly, which had just learned to flap its new wings, died instantly.

I felt a pang in my heart. So beautiful, yet so fragile.

Ale placed the butterfly carefully into a triangular envelope of papillote paper. It can keep the wings of butterflies undamaged for a long time.

*

In addition to Ongen’s captively bred Ornithoptera priamus, he obtains a variety of specimens from butterfly hunters on Seram Island.

He tells me he pays for silk nets and other equipment for people who want to join the hunt during butterfly season each year. These hunters roam the forest for weeks at a time collecting as many desirable butterflies as possible.

Ongen says he cannot control whether the hunters catch protected butterflies.

“There can be hundreds of people, and the result is thousands of butterflies. They bring their equipment, then go into the forest far away. I go there to collect the results every few weeks. They bring up to 30,000 paper [envelopes], all filled.”

Ongen and his employees sometimes also hunt butterflies around the breeding center. Unlike capturing butterflies in the deep forest, hunting around the flower-filled breeding center is easy, almost effortless.

“What are those pieces of paper for?” I say, pointing to metallic blue sheets strung onto some branches.

“To trap [Papilio] ulysses, because they only come down when they see their friends.”

Sure enough, a moment later, the iconic Papilio ulysses butterfly, with its iridescent black and blue wings, flies low toward the glimmering the sheets of paper. Ongen jumps up and grabs the handle of his net. Even while he is talking and joking with us, he is constantly alert to his surroundings. He runs straight to the flowers.

“Got it!” he exclaims.

As before, Ongen kills the butterfly by pinching its thorax and places it in a triangular papillote envelope. That afternoon, in less than three hours, he and his employees capture dozens of different species of butterflies, including Papilio ulysses, Troides helena, Troides hypolitus, and Taeneris selene.

“We just send them like this, and the collector will open the wings and arrange them in a glass frame,” says Ongen.

I imagine the satisfaction of the collectors when they receive the packages. Then, I feel sorry that no matter how much they pay, they will not see their butterflies as they were when alive and flying free, showing off their wings in the wild.

How futile the collectors’ efforts are. They chase beauty in a glass box, a shadow of the resplendence of nature.

Illegal Trade, Mining, Deforestation

When we arrive again a few days later, Charlie, another employee, is busy repacking butterflies. In front of him are baskets of various sizes containing butterflies recently collected from Seram Island. All are sorted by quality and species. Charlie takes special care as he places the Ornithoptera priamus specimens into a different container.

“This could be a holiday to Bali!” he says happily, showing me his basket of Ornithoptera priamus butterflies.

From this captive breeding center in the middle of the forest, butterflies are packed in cardboard boxes and sent to a middleman in Jakarta. The middleman organizes the export of the butterflies to various countries. Ongen, as an initial supplier, sells the butterflies for up to US$200 each, depending on the species and quality. By the time the butterfly reaches the international market, its price has increased by many times.

Ongen can produce 75 to 100 Ornithoptera priamus cocoons each season through captive breeding. Of that number, some are released, some fail to hatch, and the rest he sells.

“In a year, 50 butterflies from captive breeding is good enough,” says Ongen.

Indonesian regulations on catching, trading and exporting butterflies are complicated but full of exceptions that leave many opportunities for cheating.

To operate, a butterfly seller needs to obtain a license from the Natural Resources Conservation Center (BKSDA) and the Environment and Forestry Ministry. Protected butterfly species, such as Ornithoptera priamus, may only be sold if they are bred in captivity. Meanwhile, a certain number of specimens of unprotected species may be caught in the wild and sold each year.

Butterfly entrepreneurs like Ongen face a complicated licensing and quota system.

Ongen says he cannot rely solely on captive-bred Ornithoptera priamus to make a profit. To fulfill his business targets, he also sells other species of butterflies. However, he believes the quota is too small to be economically viable. He even suggests that the state regulations are deliberately made to be broken.

“We have to spend tens of millions of rupiah to manage our business. If the quota is only 100 butterflies per season, what are we going to make? Meanwhile, in the forest, we can get up to tens of thousands of butterflies per season. Do we want to export only 100 of them? That doesn’t make sense. We shouldn’t [be required to have] any license from the very start, right?” he says.

While he does have a license, Ongen has felt obligated to enter the black market this year.

He says the market demand for butterfly specimens is always high and that the internet has made black market transactions easier to conduct, accessible to all, and harder to identify.

Facebook is currently the biggest global marketplace for butterfly collecting, and Ongen receives many requests from the social media platform. Protected butterfly specimens are also readily found on marketplaces such as eBay and Etsy.

Both legal and illegal specimens are sold through these channels. Many sellers include purported CITES certificates, but it is nearly impossible to determine their authenticity. Others don’t even bother with licenses, real or fake, and the black market operators have little trouble with distribution.

“There are many ways to send them, or if it’s difficult, just give the officer an envelope [of cash],” said Ongen.

*

While it’s a niche hobby, butterfly collecting is a big business.

Jessica Speart, in her book Winged Obsession, spent time exploring butterfly smuggling and found that the industry is worth an estimated US$200 million annually. Each year, butterfly collectors celebrate their hobby at events like Die Internationale Insektentauschbörse in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and the Tokyo Insect Fair & Entomodena, which showcase many exotic species from Indonesia.

“I want to follow the regulations, but honestly, if the conditions are like this, the permit is just a formality. If my demand and stock exceed the export quota, I’ll smuggle the rest,” says Ongen. “If one butterfly costs Rp 100 million, it doesn’t matter. But how much is one butterfly? This business can’t run if it’s clean.”

“Even if I take thousands [of butterflies], it doesn’t matter if the forest is still there. If the forest is still good, they won’t go extinct. But if the forest is gone, that’s a problem.”

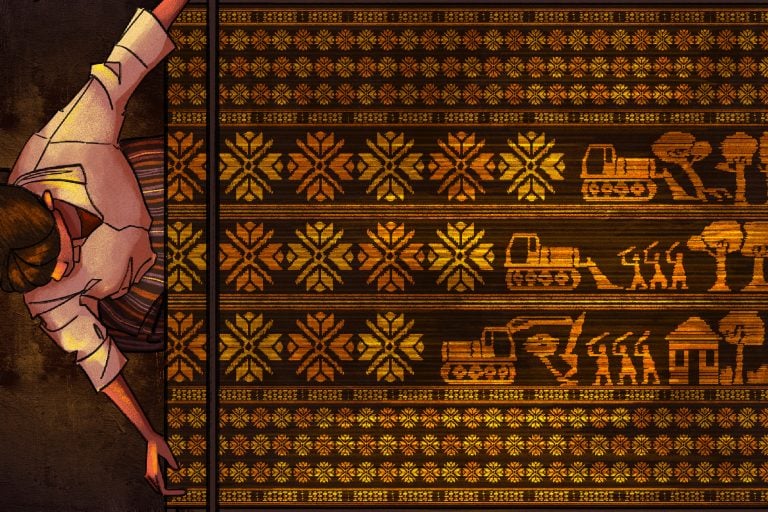

Now Ongen has a concern. A sand quarry near his breeding ground continues to encroach on the forest from which he sources many of his wild butterflies. The operation, allegedly owned by a local official, expands as if it has no boundaries. The sound of chainsaws can be heard day and night, clearing forests along the river and preparing the land for excavators, which in turn leave only bare hills and mud.

“In time, this forest will be gone. Not only the butterflies, everything will be gone. And we can’t protest because the mine is owned by local officials,” says Ongen.

*

His statement is in line with the opinion of Djunijanti Peggie, a butterfly expert from the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and founder of Kupunesia. She said the biggest threat to butterfly populations was forest conversion.

“Butterfly life is very dependent on the host plant, because often the association of butterflies with plants is very specific. If the forest is destroyed, they can’t lay eggs. As for trade, because the butterfly’s life cycle is short, whether you take it or not, it will die,” she said.

“But that doesn’t mean I’m saying it’s safe to take it blindly. If it is a protected and endemic species, the risk is that the perpetrator will face regulations,” she added.

Deforestation and land conversion have indeed been shown to be the main causes of biodiversity loss in Indonesia.

Population Review notes that Indonesia experienced the second-highest level of deforestation by country in 2024, behind only Brazil. Over the last 30 years, Indonesia’s forests have shrunk by 26.5 million hectares.

Seven of the 12 species of Ornithoptera, the genus of birdwing butterflies, are endemic to Papua. But sadly, from 2000 to 2022, Auriga Nusantara recorded that Papua lost 688,438 hectares of natural forest. In 2023, deforestation in South Papua was the worst in Indonesia, with 12,640 hectares lost.

Since 2022, Greenpeace Indonesia has been championing the cause of the Awyu tribe, who are trying to stop 39,000 hectares of their customary forest in Boven Digoel from being snatched away for oil palm plantations. Meanwhile, the food estate megaproject of the central government calls for the conversion of 2 million hectares of forest in Papua into agricultural land.

The lack of protection of forests and their biodiversity demonstrates the state’s failure to recognize Papua as what it is: the most biodiverse area of the world and the largest old-growth tropical forest in the Asia-Pacific region. An article in the journal Nature notes that Papua’s forest biomes, from mangroves to tropical alpine grass forests, support an estimated 13,634 species (68% endemic), 1,742 genuses and 264 families of animals, the richest on Earth.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has red-listed birdwing butterflies. The Ornithoptera aesacus species, which is endemic to Obi Island, is now considered vulnerable. Obi Island is being torn apart by the activities of a large nickel mining company. Apart from polluting the sea and affecting the health of residents, the nickel smelter also clears hectares of forest.

“If a mine enters, we should check whether the flora and fauna in the area are represented in the [Environmental Impact Assessment]. Or maybe only large fauna [have been registered]. Invertebrates should also be considered, especially those that are endemic, like the aesacus on Obi Island. It would be unfortunate if it went extinct,” Peggie said.

Peggie said scientists with expertise in biodiversity and conservation were rarely consulted in development projects in Indonesia. In general, she added, biodiversity was thought secondary to social, political and economic issues in the country.

“In developing countries, it is always considered more important to take care of humans than butterflies, even though, if the country is not supported by science, it will be troublesome,” she noted.

Ongen has experienced firsthand how sand mining near his breeding grounds has impacted the number of butterflies he encounters.

He said wild Ornithoptera priamus were becoming increasingly rare.

“Ten years ago, they were along the road. There were so many. At that time, the price was low,” he said.

Ecological Services and Lack of Data

It has been almost a year since Daawia has seen any Ornithoptera priamus in her garden in Keerom regency, Papua.

“It’s strange. They used to come every morning to lay eggs, but how come there are none now, even though this is the season? Why is that?” Daawia says while touching the leaves of an Aristolochia creeping up a bamboo frame.

Daawia is a biology lecturer at Cenderawasih University. She is also one of the few butterfly experts in Indonesia. In 2012, she began turning her home garden into a birdwing butterfly conservation area. Her house, about an hour away from the Cyclops Mountains in Jayapura, is within the range of Ornithoptera.

Daawia was inspired to start the at-home conservation project after seeing hectares of nearby forest turned into palm oil plantations.

“It’s just a personal project. In 2012, I was quite sick and had to take a break from campus. I thought, ‘If I am given the chance to live, I want to take care of butterflies. I planted flowers, lots of butterflies came, I was busy and forgot about the illness, and I’ve since recovered,” she said cheerfully.

Each season, thousands of birdwing butterflies come to Daawia’s garden. The most numerous are Ornithoptera priamus and Troides helena. They compete to lay eggs on the Aristolochia leaves.

Daawia’s love of butterflies began in 1994, in her early days as a university lecturer. She met Brother Henk van Mastrigt, a Dutch monk and amateur entomologist living in Papua. During his time in Papua, Henk travelled extensively, collecting insect specimens.

Now, 72,000 insect specimens, mostly butterflies, are stored in glass boxes at the Papua Insect Collection Laboratory (KSP), operated by Cenderawasih University’s Faculty of Biology. The collection is said to be the largest and most comprehensive in the Asia-Pacific region, and Daawia is currently its manager.

“Brother Henk opened my eyes to the world of butterflies, that Papua is a world biodiversity hotspot. All taxons here are the richest in the world. But insects here are still very under-researched,” Daawia says.

Since then, Daawia has been immersed in the world of butterfly science. For her, Papua is a living laboratory containing countless mysteries that have yet to be studied. Despite insects’ enormous ecological services, she says, they receive little attention.

“Sadly, even in culture, we tend to only pay attention to large mammals. The ones that are used as totems are animals whose benefits are directly visible, even though, if we think about it, insects are very crucial.”

She pauses for a moment.

“They’re so scientifically underrated. Culturally underrated, too. Sad, eh? I’m sad, you know.”

In terms of species diversity, insects are unrivaled by any other class of animals.

According to the IUCN, of the approximately 1.5 million documented animal species in the world, 1.05 million are insects. This means they make up around 70 percent of all the animal species on Earth. And of the world’s approximately 18,000 species of butterfly, 2,400 are found in Indonesia. That number is likely to increase, as scientists believe many insects in tropical forests have yet to be identified.

Butterflies and other insects play a crucial role in shaping the web of life because of their central role in the food chain and plant reproduction.

Animals such as birds, reptiles and mammals rely on insects as a food source. This includes humans, who eat around 2,000 species of insects. In nature, some 80 percent of wild plants rely on insects as pollinators. Some flowers have even evolved specific structures to match an insect’s body shape for pollination. For example, the tubular ixora flower can only be pollinated by butterflies because other insects’ proboscises are not long enough.

The web of life is made up of complex interdependent relationships between species. The loss of one species, whether large or small, can impact or even destroy the lives of others.

“Everything is so fragile. Maybe if people don’t understand, they’ll underestimate that. ‘What the heck, it’s just a butterfly.’ But if butterflies disappear, the lifespan of humans on earth is only four years. We will have crop failures, butterfly-eating birds will go extinct, followed by the extinction of other predators, and then up to the top predator, the whole pyramid will be destroyed, including us humans,” Daawia says.

“But this is what is in the brain of the researcher. In the brains of policymakers, it’s different,” she adds.

This explanation of serial extinction recalls the popular term the “butterfly effect”, which is commonly used in fictional stories to describe how one small action, such as the flap of a butterfly’s wing, can have big, unpredictable consequences far into the future. Unfortunately, the effect may be more than just a metaphor.

“Yes, for us, it could be very real,” says Daawia.

*

“The Collapse of Insects” report released by Reuters in 2022 found that the world had lost 5 to 10 percent of its insect species in the last 150 years, some 250,000 to 500,000 species. The population decline could not be attributed to one cause alone. Insects have faced deforestation, land conversion, industrial agriculture, pesticides, light pollution, illegal hunting and a worsening climate crisis. The decline is predicted to continue, although estimates of the scale vary.

In 2010, the IUCN recorded that nearly one third of Europe’s native butterfly populations were in significant decline. In Mexico, the monarch butterfly population fell 26 percent as a result of rising temperatures stemming from the climate crisis.

Heron Yando, a 24-year-old biology student who helps Daawia manage the lab and conservation garden, compared the diversity of the nymphalidae family of butterflies between oil palm plantations and secondary forests to determine the impact of forest conversion.

He found more species in the secondary forests but lower populations of each. Conversely, there were few species in oil palm plantations but large populations.

“In terms of sustainability, it is better if the population is small but diverse, a sign that the forest has better ecological stability,” he said.

“If you study ecology, the main requirement for sustainability is to maintain diversity, so no one is more dominant,” he added.

Heron conducted the study for his undergraduate thesis. In the future, he would like to continue his studies abroad so that he can do more research on the insects of Papua.

Over the past decade, the Earth has experienced a significant rise in land and sea temperatures.

The year 2024 broke records as the hottest year on record, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. The global average temperature has already crossed the threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average, from 1850-1900. A study in the PNAS journal found that if temperatures continued to rise, the world would lose one third of its animals and plants in the next 50 years.

Daawia suspects that the decline of Ornithoptera priamus in her conservation garden is related to this fact.

“If we had a database before the climate crisis, we could just compare it, but now, what are we going to compare it with? We don’t have the data,” she says.

“There could be many species that disappear before we have time to study them. The lack of data means we don’t know what we have or what we have lost.”

Amid the onslaught of gloomy news, tending to the conservation garden is Daawia’s way of nurturing hope.

“Butterflies will not go extinct so long as the ecosystem is maintained, so I focus on propagating Aristolochia only. That way I automatically protect the butterflies, protect the birds, and so on, because everything is interrelated.”

*

With no Ornithoptera priamus coming to the garden, Daawia takes us on a tour of several forested locations at the foot of the Cyclops Mountains. Each morning for seven days, we go in and out of the forest, following the riverside paths that Daawia remembers as habitats for birdwing butterflies. We encounter many species of butterflies, but not a single Ornithoptera priamus.

“Logically, if Ornithoptera priamus, which is the most common green birdwing butterfly, is already rare, what else is there? I need to find a brood so that the ones around the house can come back.”

“That’s a Graphium!” Daawia exclaims suddenly.

It takes her less than a second to recognize each butterfly species, just as we might recognize actors or musicians on television. At her home, the motifs on her wall vents and tablecloths are all butterflies.

“Graphium flies wildly and irregularly. Ornithoptera priamus, a strong flyer, likes to patrol because it is territorial. Each butterfly has a different behavior. Beautiful, huh?”

She sighs, “How come we destroy it so easily?”

*

On our seventh day, the day before our flight back to Java, we finally encountered an Ornithoptera priamus.

The rain had just stopped. The retreating clouds allowed pillars of sunlight to warm the forest again. The cicadas, which had been silent before, began to buzz as if they were part of a forest orchestra. We saw it gliding through the air, perhaps looking for a forest betel nut plant on which to lay its eggs. The female, brown in color, is even larger than the male.

We caught it with a silk net. With sparkling eyes, Daawia put it in a large acrylic cage, fed it honey water, and brought it to the main enclosure in her garden. For Daawia, the female Ornithoptera priamus butterfly brought hope for the birdwing butterfly’s continued existence.

“After it becomes a butterfly, what do you do with it, Bu?” I asked.“Let go. If we love something, we let it go. Let it go and grow.” Her eyes shifted from the butterfly in the box. “I think we should do that with everything, right?”

—

Ongen, Ale and Charlie are pseudonyms used at the request of the subjects for safety reasons.

This piece, originally published in Indonesian, was translated by Astrid Reza.