Workers along the supply chain of the industrial fishing industry in Benoa, Bali, suffer from poor working conditions, including unfair wages and excessive working hours.

A dozen dock workers gathered on the shore of Kedonganan Beach in Bali. They gazed far out to sea as they waited for a fishing boat carrying dozens of yellowfin tuna to come ashore.

Tuna rarely landed at Kedonganan these days, said one of the workers.

“Only this boat has come in today,” said Amri, the worker, who hailed from East Java.

Amri and his colleagues are piece workers. They unload a wide variety of fish, from mackerel and skipjack tuna to shrimp and squid. Their pay ranges from Rp 50,000 (US$3.24) to Rp 200,000 per day, depending on the volume they unload.

Amri and the other workers took turns carrying the over two dozen yellowfin tuna for weighing at a facility known as the Kedonganan Fish Landing Base. The staff there took note of the weights of the individual fish, in the range of 50 to 70 kilograms.

Most of the tuna unloaded at the facility is sent to fish processing facilities at Benoa Port, while the remainder is sold at the nearby Kedonganan Fish Market.

In 2020, Bali recorded the highest tuna fisheries value in Indonesia at Rp 281.43 billion with a production volume of 6,144 tons. It was far higher than that of Jakarta at Rp 70.48 billion with a volume of 2,185 tons.

Benoa is Indonesia’s second-largest fishing port after Muara Baru in Jakarta in terms of the quantity of fish landed, the scale of industrial processing and the quantity of storage and exports.

From January to June 2023, Benoa took in 9,790 tonnes of fish with a value of Rp 208.9 billion. The figure is lower than the 15,065 tons recorded in the same period in 2022, worth some Rp 366.4 billion. Yellowfin tuna tends to be the biggest contributor to this figure and was so in 2023, netting Rp 59.8 billion, followed by squid at Rp 45.3 billion. Around 70 percent of Benoa’s production is exported.

However, the workers at Benoa Port get only a meager taste of this maritime bounty. They are stuck in poor working conditions, both on land and at sea, with miniscule wages, long working hours and unfair treatment.

Invisible Toil in Tuna Factories

Seeing Denpasar’s sunset is a luxury for Rahayu, a fisheries worker who requested anonymity for the purposes of this report. She is often at work well into the night, toiling among cuts of pelagic fish.

“This is only the third day I’ve been able to go home in the afternoon. I’ve been doing overtime for the last month,” Rahayu said in November 2023.

In her mid-20s, Rahayu migrated from East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) to Bali after finishing vocational school in the hope of landing a decent job.

“There are many hotels and villas in NTT, but it’s hard to get a job there. I could work at some shop there, but then I’d only earn Rp 500,000 per month. I could barely do anything with that amount of money,” she said.

Upon arriving in Bali, Rahayu found employment as a domestic worker. It was not the job of her dreams, but she could not afford to lament over it. She thought it was best to keep the job while she sought other opportunities.

One day, a fellow migrant friend told her about a vacancy at PT Hatindo Makmur, a fish processing company at Benoa Port. Rahayu applied for the job and eventually got it.

PT Hatindo Makmur began operations in 1999 and has since grown to become the biggest seafood processing company and exporter in Bali. The owner is a Taiwanese citizen named Ko Shun Jung.

The company mainly deals in tuna, including the yellowfin, bluefin, big eye, skipjack and albacore varieties. It also processes swordfish, mahi-mahi, marlin, oilfish, kingfish, moonfish, squid, and octopus into filets, steaks, and frozen foods, among other products.

PT Hatindo Makmur has obtained food safety certifications from the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and the British Retail Consortium (BRC), requirements for trade on the international market. Their clients are spread across the United States, China, Taiwan, and the Philippines. In 2019, PT Hatindo Makmur exported 1,007 tons of fish products. It exported between 230 and 746 tons in the following years.

But Rahayu has yet to experience the prosperity she was hoping for when she moved to Bali. The company pays her a base salary of Rp 800,000 per month, a transportation allowance of Rp 25,000 per day and a meal allowance of Rp 10,000 per day. In a month, Rahayu takes home a total of Rp 1.85 million, far below Bali’s minimum wage, set at Rp 2.71 million in 2023. (In 2024, Bali’s minimum wage was increased by Rp 100,000)

With that income, Rahayu must rack her brains to meet her needs. She divides the small pay among rent, personal needs, remittances for her family in her hometown and, when she’s lucky, savings.

She often works longer hours than usual. On paper, the company requires six working days a week with a day off on Friday. The workers punch in at 8 a.m. and out at 5 p.m. with a 40-minute break in between.

The company, however, regularly asks employees to work overtime, especially when there is a large haul of fish. The workers often work to 9 p.m., or midnight on the heaviest days, and often come in on Friday, their only day off.

Rahayu complained about the low overtime pay of Rp 5,700 per hour.

“Everyone complains about it. We probably wouldn’t mind if they paid us Rp 8,000 to Rp 10,000 per hour. But now, when we pull four hours of overtime, we only get Rp 20,000,” Rahayu said.

Based on her estimates, Rahayu and other Hatindo workers work four to eight hours of overtime a day, which exceeds the maximum set by the Job Creation Law of four hours per day or 18 hours per week.

“When I was a domestic worker, I had time for my family because I started in the morning and went home in the afternoon,” Rahayu recalled. “But working here, I get more distressed because I don’t have time for my family.”

The overtime has also taken a toll on her physical health. Most recently, Rahayu suffered from diarrhea and fever. Her doctor said it was due to fatigue and told her to rest.

“If we take too many days of leave, the office will call us. But […] there’s no day off there. People are tired. So sometimes we must take leave.”

Amid the scarce time off, Rahayu often works through her menstrual pains. One time, they got so severe that she decided to just go back to her rented room.

Workers walk into PT Hatindo Makmur’s factory at Benoa Port in Bali. PT Hatindo Makmur, owned by Taiwanese citizen Ko Shun Jung, has been operating since 1999 and is one of Bali’s biggest seafood processing companies and exporters. (Project M/Felix Rio Prabowo)

Rahayu is now caught in a dilemma. She realizes she has been undercompensated in her tough job despite the overtime hours, but she is not brave enough to leave it.

She is unsure if she would be able to get another job. She is worried about having to adapt to new people in a new place. She prefers to endure her current situation and hope that Hatindo will improve its workers’ welfare.

“I just hope that they will increase our wages and overtime pay. And about the holidays, if we’re supposed to have Fridays off, then let us rest, no matter how much fish there is,” she said.

The sky over Denpasar began to turn a deeper shade of black. The stars shone brightly. Rahayu said she had to go to bed early as she had just learned from her WhatsApp group that she would have to do yet more overtime work the next day.

“Ugh, my body feels weak. In the morning, I’m already thinking about working overtime until late at night,” she said.

“Got to keep the spirits high so I can fly high!” she added with a laugh.

Project Multatuli requested an interview with PT Hatindo Makmur commissioner Komang Sri Mahari at her office, but she was not in the office. She had not responded to our messages by the time this article was published.

Adrift Aboard a Tuna Vessel

It was scorching at Benoa Port that afternoon, reaching a high of 31 degrees Celsius. Luckily there was still a wind blowing. Alam, a fishing boat crew member in his late 20s, went on the deck of the fishing vessel he was on for some fresh air. Before Alam, a dozen crew members had outfitted the boat with longline fishing gear to catch tuna.

The vessel is owned by PT Bandar Nelayan, one of the largest seafood companies in Bali. Founded in 1995, its owner is a former captain named Kasdi Taman. Kasdi also serves as chairman of the Indonesian Longline Tuna Association (ATLI), which shares the same office address as Bandar Nelayan at Benoa Port.

The company operates in both the upstream and downstream sections of the fisheries industry. It owns and operates tuna and squid fishing boats, processing factories and restaurants. It also exports processed fish to several countries, including the US and Vietnam.

From 2019 to 2023, PT Bandar Nelayan exported thousands of tons of fish per year. Its highest annual export figure was 1,897 tons in 2021, while its lowest was 1,251 tons in 2023.

PT Bandar Nelayan’s headquarters on the north pier of Benoa Port. (Project M/Felix Rio Prabowo)

Soon, Alam and the crew of the Bandar Nelayan vessel would travel to Fisheries Management Area (WPP) 573 in the waters of the Indian Ocean south of Java and further on to the high seas in search of yellowfin tuna, albacore and marlin.

Alam has worked on five tuna fishing trips on the Bandar Nelayan boat. In a single trip, the crew spends seven to 10 months at sea.

“Actually, I’m already reluctant to go on a boat like this,” complained Alam, who asked to use a pseudonym for this report, in November 2023. “When it rained, it was miserable, and I couldn’t rest. But the ship kept sailing and wouldn’t stop.”

On the boat, Alam worked up to 20 hours a day non-stop from 4 p.m. to 12 a.m. the next day. When the weather got bad, the work doubled. He’d work at the stern during the day and move to the bow of the boat at night.

Those working hours exceed the limit stipulated in Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry Regulation No. 33/2021, which sets the maximum working period at 14 hours a day or 91 hours a week.

“Working hours on the ship depend on the captain,” said Alam. “We only slept for four hours.” On a vessel, the captain is at the top of the hierarchy.

The work took a toll on Alam’s health. Sometimes he would get feverish or suffer from diarrhea, dizziness, and nausea. Making things worse were the cold and windy weather and the drenching ocean spray.

All that was available on the boat was over-the-counter medicine. He often forewent medication and sought to recover on his own. Owing in part to the captain’s mercy, he was allowed the day off when he was sick.

“Just don’t get spoiled because of it,” he said. “The key is eating. One or two spoons of food should fill your stomach. If you vomit, eat again. After a while, you get used to it. Shower and wash your hair. Sleeping it off also helps.”

If crew members suffered serious illness while at sea, Alam said, the captain would allow them to go home. However, the boat would not take them to a port. They would, instead, board a fish-collecting boat that came every five months to take the catch. Alam decided to stay on the vessel because he would lose out on wages if he went home.

“If crew members are sick and ask to go home, they aren’t paid. Our wages would be forfeited. Only when we finish the contract do we receive both incentives and wages,” he said.

Another thing that made the ship crew vulnerable to illness, said Alam, was the limited food supply. The vessel had chicken, eggs, red meat, instant noodles and vegetables, among other foods, that were supposed to last the crew for months. (One fishing boat can accommodate between 10 and 30 people, depending on the gross tonnage.) However, in Alam’s experience, the food stocks only lasted for two to three months. They spent the following months eating instant noodles and the fish they caught.

“When there’s tempeh and tofu, it’s delicious. But eating fish all the time until you get home, you’re bound to get bored. Sometimes, I ate fish eggs as a side dish. It tasted like sausage, especially when mixed with fried noodles. It was delicious,” said Alam.

Alam is still considering leaving PT Bandar Nelayan. He appears to be exhausted from working on the ship, but he can’t help thinking about his family.

Even so, he was agitated that the company had not been transparent about workers’ wages. Alam had briefly thought of returning to his village and looking for work on land or working for different shipping companies, whether domestic or foreign.

“Longline ships abroad provide better salaries. In Korea, some people say, you can get Rp 30 million to Rp 35 million a month, including incentives. The money and the work are on par. It’s not like our own country’s ships where the crew is paid cheaply.”

According to Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry Regulation No. 33/2021, wages for a ship’s crew must consist of two components: a monthly salary and a profit sharing portion. The monthly salary includes a minimum basic salary equivalent to the regionally regulated minimum wage, a minimum sailing allowance of 3 percent of the base salary, a minimum production bonus of 10 percent of the total production value and overtime pay of a minimum of 25 percent of the daily sailing allowance.

The profit sharing component, meanwhile, is determined through an agreement between the fishing boat’s owner and the crew. However, if the vessel’s owners do not make money on a trip, they are only obligated to pay the crew half the regional minimum wage.

In practice, Alam receives Rp 60,000 per day and an incentive of Rp 100,000 per each ton of catch. If he is lucky, he can take home Rp 32 million to Rp 45 million per year, which he will only receive once the contract ends or when the boat returns to port.

These figures are still gross estimates because there are deductions for cigarettes consumed on board and advances paid by ship owners to the crew before sailing, which are commonly sent to their families or used to cover daily needs as crew members wait to receive their sailing schedule.

“The calculations at Bandar Nelayan are not transparent. For example, if I borrow Rp 5 million, the loan could be Rp 6 to 7 million when I get back home,” said Alam.

Ponco, not his real name, also experienced opaque wage calculations at Bandar Nelayan. The salary promised to him was not the same as what he eventually received. Feeling taken advantage of, Ponco decided to move to another company.

“There are no rules when it comes to paying salaries, just like when I worked in construction. I work at a company [outside of the construction sector], but the financial terms remain unclear,” Ponco said.

On a Bandar Nelayan boat, Ponco sailed for seven months to the Arafuru Sea (WPP 718). Initially, he was promised Rp 60,000 per day and an incentive of Rp 13,500 per kilogram of catch, which would be paid after the ship returned to shore.

Poncho had calculated that he could bring home at least Rp 12.6 million, based on the daily wages and not including the incentives. However, the wages he received were far from his expectations.

“I forgot [the exact amount] because there was no pay slip. But if I’m not mistaken, it was only Rp 4.2 million,” he said. “There were many deductions that didn’t make sense, such as a deduction for making a sea book. There were also deductions with no detail as to what they were for.”

Ponco said he had given up on working aboard Bandar Nelayan’s vessels. Now he works on a ship owned by a Chinese company with a route that goes beyond Indonesian waters. Poncho said he was now making more money than when he worked on local ships.

“I don’t fully blame the company,” he said, “If the government had been firm, the company wouldn’t have been so arbitrary.”

Project Multatuli reached out to PT Bandar Nelayan director Richi Richado by phone and visited his office at Benoa Port to request an interview. He did not respond.

Trials of a Squid Vessel

Obi and Santo, not their real names, were forced to abandon their 10-month contract to sail on the fishing boat Sanjaya, owned by PT Sentral Benoa. They became seriously ill in their fourth month on board.

“My stomach was inflamed, and it hurt like death. I couldn’t even stand straight. When I went to the doctor, they said I had high stomach acid and appendicitis,” said Obi, who is in his 30s.

“I went to the clinic and the doctor said I was suffering from a urinary tract infection. My stomach still hurts to this day. I no longer can lift heavy things,” said Santo, who is around Obi’s age.

Initially, Santo and Obi fished for squid, cuttlefish and mackerel in the waters of the Maluku Sea (WPP 715). In the first and second months, things went normally, although not many fish were caught. Their working hours were within the standard range.

They usually worked from 5 p.m. to 6 a.m. the next day, standing throughout the shift. Then, they rested until 3 p.m.

“The work was not too hard. I was just tired of standing. Sometimes I sat for a while. But if the captain saw, I didn’t feel it was okay to sit,” said Santo.

“The rest time was also quite good. It’s not like on the tuna vessels,” Obi added.

Their main concern was food availability. The Sanjaya’s food supplies were limited. When the vessel departed, it was carrying a range of supplies, including chicken, vegetables, red meat and eggs, but the stock was rather small.

“It didn’t even last for two months,” said Santo. “Because on a ship, there are many people, and their appetite is greater than when on land.”

Throughout the remainder of the voyage, they ate whatever food they could obtain.

“There were no side dishes. There were no vegetables. We ate old fish sent by the company. They were boiled, not fried, because there wasn’t enough cooking oil,” said Obi.

They drank water stored in the hold. Sometimes it tasted of the vessel’s fiberglass hull.

“Even though the hold was washed and the water was boiled, traces of the fiberglass were still there. The doctor said my urinary tract was infected perhaps because I kept standing and drinking water from the cargo hold,” said Santo.

“Rainwater was better than the water on that ship. Sometimes sea water got into the hold so [the water in it] tasted a bit salty,” added Obi.

In the fourth month at sea, Santo and Obi started to become ill. At first, they felt feverish and dizzy, and after a while, they had stomach aches. Santo noticed blood in his stool. Obi couldn’t even stand up.

Like on tuna vessels, squid vessels only carry over-the-counter medicines. If crew members become seriously ill, the captain will allow them to rest.

“It was difficult to walk. It hurt terribly,” said Santo.

“It felt like I was half dead,” Obi recalled.

The two finally asked the captain’s permission to be sent home. But it was not that easy.

The ship was still in the middle of the sea. They had not met the catch target. It was impossible to turn the vessel ashore. The only way to get to land was to wait for the collection ship to arrive. They were patient for two weeks before they finally reached Benoa Port.

On land, their wages were withheld. The company asked Obi and Santo to wait a week because their pay was still being calculated. All the while, the company detained their national identification cards and books.

Obi and Santo were stranded on land without money, medical treatment, or a place to stay. They had no relatives in Bali.

“Luckily, we had a friend, so we stayed at his boarding room. If he weren’t there, we would have probably just stayed on the ship and endured the pain,” said Santo.

The company did not inquire about the reason for their early return. It was Obi and Santo who proactively informed their employers of their situation. However, the company, they said, paid little heed and still asked Obi to unload vessels.

“The company told us to write a statement that if an accident or death occurred, the company would not be held responsible. The office has the letter,” said Obi.

Throughout that week, they went back and forth to demand their wages and personal documents while enduring the pain. They eventually gave up and asked for the help of Destructive Fishing Watch (DFW) Indonesia. DFW staff took them to a clinic for treatment and advocated for their wages.

“I don’t have [national health insurance]. My treatment was paid for by DFW Indonesia. We couldn’t afford to just wait for the company. It had already been too long,” Santo said.

In the doctor’s examination, Obi was found to be in a critical condition and in need of surgery. However, his family had to approve the procedure, and Obi had no relatives in Bali.

The company stalled in its disbursement of their wages. Santo and Obi were upset because the calculations were not transparent. Their daily wages were set at Rp 35,000 and the bonus at Rp 8,000 per kilogram. For four months of work, Santo should have pocketed Rp 7.2 million (in both daily wages and his bonus). However, Rp 5 million was deducted from that amount to cover pre-sailing expenses.

“Before I went to sea, I was waiting for almost two months on land. I gave Rp 3 million to my family at home. The rest was for my needs on land,” he said.

This meant Obi only brought home Rp 2.67 million. He believed that the company had miscalculated his haul: while he had brought in 300 kilograms of squid, the company recorded only 200 kg.

“I was confused, the captain only recorded 200 kg under my name. Also, I was considered to have gone home for no reason, so my daily wage was calculated at Rp 10,000 a day. I went home because I was sick. How come they said there was no reason?” Obi said.

Obi became increasingly nervous when the company showed him a debt record of Rp 13 million. Obi indeed owed some money before setting off, but it was only Rp 4.6 million. He used the money to support his life in Bali while waiting for the ship to sail.

After negotiations accompanied by DFW, the company agreed to write off Obi and Santo’s debts. The company also funded their trips back to their hometown.

“I don’t think I will work at sea ever again. I’ll work on land. Working at sea is quite tormenting,” said Obi.

“Right now, I’ll just stay on land. I haven’t thought about going back to the sea yet. I’m still scared, and there’s a bit of trauma,” said Santo.

Project Multatuli requested an interview with the director of PT Sentral Benoa Utama, Rudy Herianto, at his office. However, a receptionist said he was not in the office. A few moments later, we called the office phone, and the receptionist said the same thing: Mr. Rudy was not there and rarely came into the office.

Project Multatuli brought the crew members’ complaints about wages at the two companies to I Nyoman Sudarta, the secretary-general of the Indonesian Longline Tuna Association (ATLI). He denied the claims and said crew members earned “high wages”. However, he said, the “high wages” were not from the monthly salary but from the bonuses for their catch.

ATLI is the trade group for ship owners and processing companies in Indonesia, including at Benoa Port. It has 144 members, consisting of 22 companies and 86 individuals in the fishing sector, eight processing companies, eight agency companies, two fishing ship dock companies and 18 non-business individuals.

Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry Regulation No. 33/2021 requires crew members’ wages to consist of a monthly salary and a profit-sharing portion.

However, Sudarta said the companies could simply choose one of the two components of the wage model and adjust it based on an agreement with the worker. The results of the agreement, he said, would be recorded in the maritime work agreement document.

“[Monthly salary and profit sharing] are choices,” he said. “We, instead, adhere to the maritime work agreement.”

“The important thing is that the worker earns an income that is not less than the regionally regulated monthly minimum wage. The salary here is already at the regionally regulated minimum wage of Rp 3 million,” he said. “If the crew get both incentives and salaries, the company could go bankrupt.”

Maritime Work Agreement

Even though workers are supposedly bound by a contract called a maritime work agreement (PKL), there are still crew members who do not have a PKL and those who do have one often do not understand its contents.

Obi was in the former group. Santo, meanwhile, signed the PKL document before sailing but did not have time to read it or make sense of its contents because the company had quickly taken it back.

“After I signed it, the document was taken back right away by the company,” said Santo.

Poncho never signed the PKL. His employment contract was verbally conveyed by the ship’s captain: “So there is nothing to support me if I want to report any misconduct.”

A work contract is legally required to ensure the welfare and work safety of a ship’s crew. Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Regulation No. 33/2021 stipulates that a maritime work agreement must include the wage structure, working hours, crew members’ identities, the identity of the ship owners and the ships, as well as the type and duration of the contract.

Destructive Fishing Watch (DFW) Indonesia once surveyed workers’ conditions at Benoa Port. Out of the 173 fisheries workers surveyed (115 crew members, 34 processing facility employees, seven ship captains, nine engine room heads and eight ship/factory technicians), they found that 46 percent of crew members had PKLs while 30 percent both lacked one and did not understand what a PKL was.

Most crew members did not fully understand their PKLs because they did not have much time to read and study them.

“The crews confirmed that the process of signing the maritime work agreement was very fast,” wrote DFW in the report Conditions of Fishery Workers and the Fishery Industry Supply Chain at Benoa Port, Bali Province.

In addition, signing a maritime work agreement is seen as a mere administrative requirement to allow for immediate departure. This was confirmed by a staff member at the Benoa harbormaster office, Roisul Maarif. He said he only read out the contents of the PKL in front of the crew members and the company’s representatives.

“There must be at least crew representatives in our office. Later the harbormaster will read the contents. If they say they’re okay with the contents, they sign it, which means they agree to the contents of the PKL,” Roisul told Project Multatuli.

Two copies of the agreement were produced, one to be kept by the company and one by the crew member, Roisul said.

“We urge and require every company to provide a copy of the agreement to the crew. It’s mandatory. The company should have given it,” said Roisul.

I Nyoman Sudarta of the Indonesian Longline Tuna Association claimed that companies did not intentionally refrain from providing the crew member a copy of the agreement, but rather “kept the document so that it would not be thrown away” by the crew member.

“The crew may consider the document unimportant. Eventually, [the company decided] not to share the copy. But the company will keep it safe, it is there. Just ask the company for it,” said Sudarta.

Broker Problem

A network of ship crew brokers adds yet another complicated layer to the dark side of tuna and squid fisheries workers in Benoa.

Alam once received an offer from a broker in Java to work on a fishing boat with promises of big wages and incentives. Luckily, Alam was circumspect. He gathered information from his fellow crew members before responding.

“There are many brokers in Java who seek crew members for Bandar Nelayan. Don’t deal with the brokers. They take a Rp 1 million deduction from our salary. Don’t use Facebook either. It’s better to ask friends who have sailed before,” said Alam.

The DFW Indonesia survey found that 48 percent of Benoa vessel crew members got their jobs from brokers and 27 percent from friends or relatives. Some 13 percent, meanwhile, registered directly with the company, while 11 percent were invited by the ship captain and 1 percent found the job through Facebook.

Unfortunately, recruitment is not regulated in Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry Regulation No. 33/2021. That matter, according to DFW Indonesia, must be addressed by the government through a revision of the regulation.

“Ministerial regulation No. 33/2021 should have regulated the recruitment system as the first step to the improvement of ship crew management so that there are no loopholes for violations and works of agents that often harm workers,” wrote DFW Indonesia.

However, Sudarta of the Indonesian Longline Tuna Association (ALTI) brushed off complaints that such brokering still occurred at Benoa Port. Each shipping company, he claimed, had representatives in various regions of Indonesia to recruit prospective crew members.

“There could have been brokers before, but eventually it is the company hiring. We believe it was not a broker, but a company staff member,” he said.

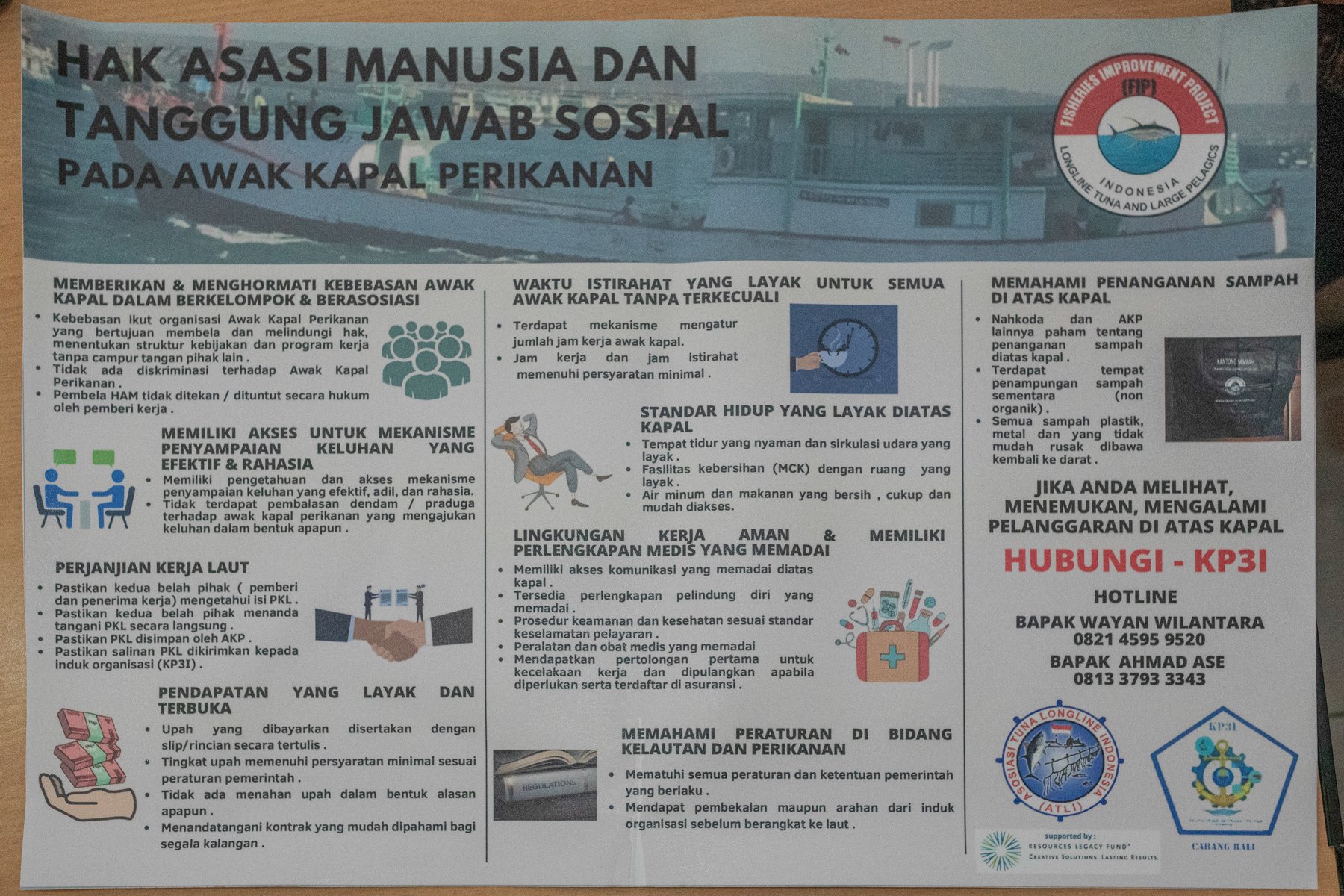

ATLI leads a fishery improvement project (FIP) with 22 participating fishing companies and 19 processing companies in Indonesia.

FIPs emphasize sustainability in the supply chain of the fishing and fisheries processing industry by prioritizing transparency, traceability, compliance with international standards and social responsibility. The procedures seek to to uphold human rights, proper working conditions and local communities’ involvement in fishing activities. The aim of implementing the FIP commitment is to earn a Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification that will help local fishery businesses market their products in the international market.

“All companies in Benoa have complied with the FIP […] because they are dealing with the market. The market will trust the FIP,” said Sudarta.

Regulatory Overlap

Like most problems in Indonesia, employment issues at Benoa Port are tangled in problems of governance and regulation.

A Bali Manpower and Mineral Resources Energy Agency official acknowledged that her office had not been able to actively supervise ship crews, except for those working in the fish processing units.

“On one hand, we are implementing Law No. 13/2003 on labor, but there is also Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry Regulation No. 33/2021. To be honest, we have not been able to harmonize both regulations,” the head of the agency’s Industrial Relations Development and Labor Inspection Department, Meirita, told Project Multatuli.

“We keep doing labor inspections. We go to companies, although during our visits we implement several Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry regulation requirements [instead of the Labor Law],” added labor inspector Ni Wayan Winiarti.

They said there had been discussions about potential joint supervision. All stakeholders, such as the ministry, the Directorate General of Sea Transportation and the air and water police corps, would be expected to work together and to complement one another.

“[The inspections] will be under the head of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Agency. This is still a plan, and we have not received any follow-up,” said labor inspector I Wyn Gd Dedy Wirawan.

Currently, the harbormaster and port authorities are the first to address crew members’ labor complaints. If the issues persist, they are brought to the Bali Manpower Office.

“The crew members have a maritime work agreement. If the harbormaster and port authorities can handle the problem, it should be resolved there. The dispute is brought to the Denpasar Manpower Agency if there is a work accident. Then, we will be involved,” said Meirita.

In other words, the Manpower Agency has limited authority to protect the crews.

Translator: Ardila Syakriah

Read our reports on #labor and #slaveryonthehighseas: “Exploitation and Deaths of Ship Crew Members”