In 2017, I spoke at a conference on fighting child trafficking to an audience of Jakarta high schoolers. I had been working in the anti-trafficking arena for around four years with Rumah Faye, and had only recently started our safehouse in Batam, Riau Islands. Directly assisting victims of child sex trafficking had helped develop my understanding of the structural issues that caused the marginalization of certain minority groups.

But this particular conference was memorable because it made way for a new personal cause to find its way into my heart: the abolition of “virginity testing” on female Indonesian Military (TNI) recruits and the fiancées of military officers. After my talk, I found myself in conversation with then-stranger (and now-friend) Latisha Rosabelle, who created the first petition to fight such “virginity testing” in Indonesia.

“Did you know about this?” she asked me. I did not.

What made it worse was this: I am part of a military family and ridiculously proud of it. My father was a red beret, part of the Army Special Forces Command (Kopassus). Perhaps it was a little bit of blind optimism – or utter obliviousness – on my part, but I’d long admired the military for their discipline and commitment to the nation.

We had all memorized the “Hymne Komando”, and I remember muttering the lyrics to myself on my way home as I attempted to come to terms with the “virginity testing”. Maybe this “test” is not a surprise to you, but for 15-year-old Faye, the world was falling apart. How could we so proudly state that we were “rela binasa membela bu pertiwi” (ready to give up our lives for the motherland), when women in the military were not afforded their fundamental human rights?

“Virginity testing” has long been considered a human rights violation. The World Health Organization has stated that such tests have “no scientific validity” and have “no place” in modern medical practice. Andreas Harsono, a researcher from Human Rights Watch (HRW), has asked journalists and writers to put “virginity testing” in quotation marks because the term is based not on fact but on the false believe that virginity can be tested for.

Regardless, there were adamant defenders of such tests, with powerful figures claiming it was necessary to determine recruits’ “mental ideology” and that virginity was an “essential gauge” of a woman’s morality. Awesome.

Advocacy groups such as HRW had worked to fight “virginity testing” for years without success. If Pak Andreas Harsono hadn’t gotten through to them, who could? What could I do?

I didn’t know how to broach the topic. I supposed it was best to start at home.

Perhaps surprisingly, I had no real fear of speaking to my family about “virginity testing”. On the contrary, there was no doubt in my mind that they would agree the tests were inhumane. I was prepared for a fight, but not against my parents, who had long taught me that change could be achieved.

My father had long focused on community development and long-term and sustainable change. He realized that he could use his position strategically, guiding his subordinates to spearhead the community development projects he loved so much. My mother was much the same, facilitating kindergartens and women’s empowerment programs for military wives. My parents shaped my worldview with their work. Wherever they were stationed, they renovated military dorms and schools, rebuilt agricultural centers to empower local communities and created recreation centers.

My fiery anger was met with calm understanding. Despite some initial hesitation to explain the situation, both parents sat me down to explain what “virginity testing” entailed and why it was implemented. I remember being in tears of frustration, not understanding why the practice still existed. I asked them to do more, immediately thinking of what campaigns could work best to eliminate such testing. My parents, however, explained that I was in the unique position to do more than campaign from the outside. While I had worked so hard in other sectors from the outside through Rumah Faye, my ever-reasonable parents pointed out the obvious: Non-profits were powerful, but I could do something (although maybe it would be small) from the inside.

I remember bringing up “virginity testing” with two of my friends at the military complex, both of whom immediately talked to their parents about it. One faced the angriest lecture she’d ever gotten, the other, the simple assertion that those “virginity tests” were for the best. After all, how else could we be sure that a woman was truly morally upright?Click To TweetAs I saw more activity from movements from the outside, I realized there was still little internal discussion (at least from what I could see) about abolishing such tests. My parents were right. Change would have to begin from the inside, from the people who could take immediate action for institutional change. This meant that we would have to initiate discussions with the end goal of having military leaders (1) acknowledge that “virginity testing” was not a valid measure of morality, (2) highlight the medical inaccuracy of such tests, (3) outlaw the tests and (4) ensure the proper implementation of the policy change. This had to be supplemented by holding past supporters of “virginity testing” accountable and enabling women who had experienced them to receive counseling and other essential services.

The effort to achieve this goal had to begin from the grassroots, which led me to speak extensively with the Women’s Army Corps (Kowad) to learn more about their experiences.

The first time I broached the topic was with a friend who we can call Marel. She had been serving for a few years where my father was stationed at the time. Looking back, I probably should have brought it up while asking about the military application process as a whole. Instead, I asked directly if she’d gone through the test and watched as her face rippled with fear before shifting quickly back to neutrality. She shrugged and gave me a half grin as if to say, what can you do?

Everyone else I talked to mirrored her reaction. Some were angrier than the rest, but most of them were resigned to the idea that these “virginity tests” were prerequisites for enlistment. Eventually, this neutrality shifted to whispered stories of painful examinations and empty waiting rooms. Tears and confusion. Shame. Malu.

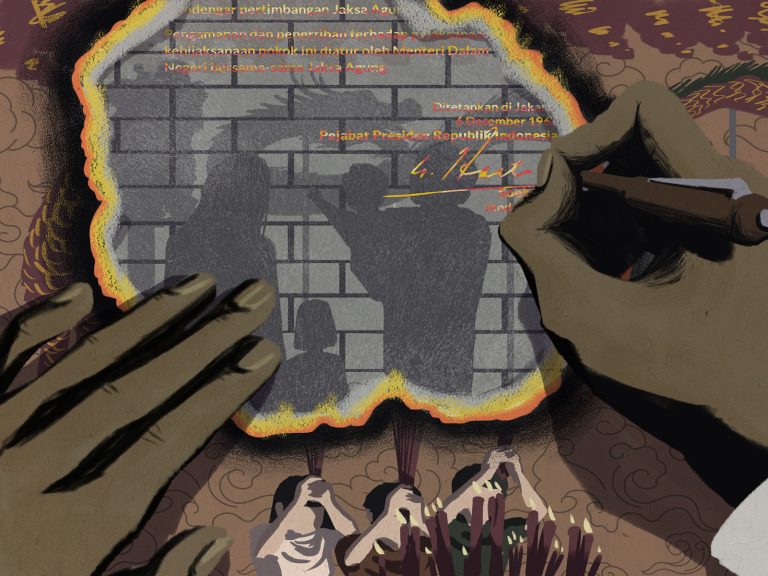

These tests have long-term impacts, with women still traumatized by their experiences more than a decade afterward. At the time, I remember feeling frustrated. If so many women felt this way, why hadn’t they spoken up yet? The truth was, the power dynamics in the military and our culture made it absurdly difficult for any type of change to be made. The hierarchical structures in place, especially in military institutions, provided little space for reformation unless supported by the most influential figures.

As I began the somewhat secret campaign, I came to the startling realization that I could not hope for change by arguing that female morality should not be measured by virginity, only that “virginity testing” was medically inaccurate. Any conversation about abolishing the practice would be met with derisive comments about supporting adultery or questions about my own moral uprightness.

I began with crazed, teenage guerrilla-style ambushes on anybody military-related I knew. I used my work at Rumah Faye to explain the impacts of the tests, drawing on the experience gained from almost eight years of working with victims of sex trafficking, exploitation and abuse. Regardless, I was met with excuses that the WHO report was “too new”, that the conversation was “too modern” and that I couldn’t do anything about it.

Looking back, if it wasn’t for my parents’ protection, I would not have gotten very far at all. I think about that a lot too, that it was only possible for me to participate in initiating dialogue because I was in the position to do so. It’s important to note that I was only able to push the conversation so far because of support from my parents and the background I had in anti-trafficking work.

Too much of the marginalization of minority groups in Indonesia is supported by the very institutions supposed to protect us. This means change can rarely be made through external campaigns alone. There has to be some sort of internal support for institutional change to take place.Click To TweetI still feel, for example, that my own voice is not truly the one that should be lifted, as I never experienced a “virginity test” myself. However, amplification was hard because no one wanted their voice amplified and identity exposed because of the Army’s hierarchical nature. Even with my own privilege, my father’s job and my own work was under threat.

Privilege is a concept crucially interwoven into this story; my own campaign was only possible because of it. It’s a portion of the story that shouldn’t be there, because every voice should be heard in cases like these.

An Army Surprise

As time passed, the movement to end “virginity testing” soldiered on, both externally and internally. On the outside, I knew, most prominently, of Pak Andreas Harsono and Latisha Rosabelle. On the inside, the picture was less clear.

In 2017, my mother introduced me to Bu Ninik Rahayu from the Indonesian Ombudsman. Ibu Ninik spoke to me at length about the tests, the work she’d done and the work that needed to be done. Over the next few years, I would keep in contact with her. She worked tirelessly to start conversations with the Army, the Navy and the Air Force to end “virginity testing”.

On my end, I secretly met with the wives of powerful military figures who had long been attempting to start conversations about these “virginity tests”. Female members of the military came forward to share experiences with us, but most declined to take up active roles, fearful of the backlash if the small movement grew. We understood this all too well. There is nothing more dangerous than seeming immoral in our country, and so everyone had everything to lose.

Despite multiple attempts to create a formal coalition against “virginity testing”, such a body was never formed. During our last discussion in May 2021, my mother, Bu Ninik and I had planned to gather a group of women to submit another formal letter to the Army Staff Command. Unfortunately, some powerful women declined to partner with us, citing concerns about adherence to tradition or that their husbands would not be promoted.

It was a long process that I could not properly track, partly because of the sheer length of the informal campaign and partly because it was all so painfully informal. To this day, I don’t know everyone involved, nor can I publicly state the names of the women I knew to be involved for various reasons. Our meetings took place behind closed doors and through informal conversations — all because the topic was too sensitive to be broached in the open.

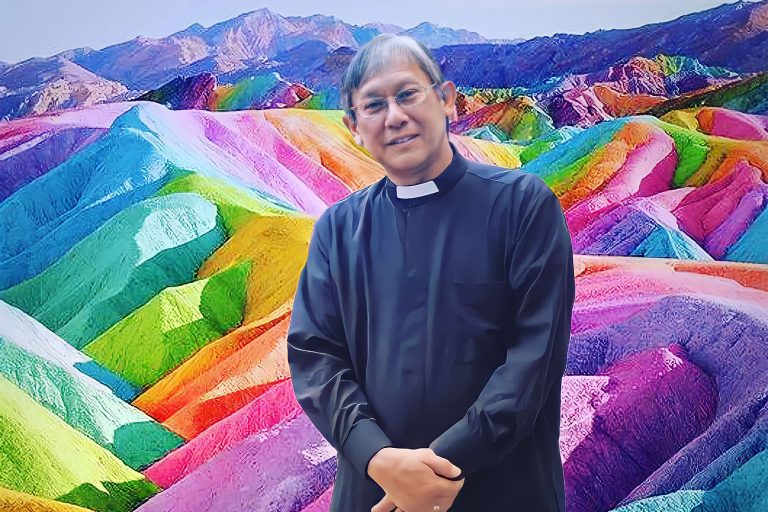

In the summer of this year, Army Chief of Staff Andika Perkasa made a surprise announcement that the Army had stopped “virginity testing”. There was so little buildup that I cannot segue into this part of the story properly. I had heard that some peers had met with him and the Navy and Air Force commands a few months beforehand, but there had been no clear update on the situation. His announcement was surprisingly understated. His early July address only began to spread in late July, thanks largely to Pak Andreas Harsono’s article for HRW.

The news had me sobbing. Part of me felt a bit disappointed that this change had come about so late, after years of discussion and campaigns, but the sense of relief was still incredible.

Now, we must hold our institutions accountable to ensure that the change will actually be made throughout the country, with clear oversight from Pak Andika.

Additionally, those who defended “virginity testing” in the past must be held accountable and apologies must be made to everyone who experienced this structural abuse. As much as there is relief, it is also crunch time to make sure the momentum is maintained. The Army is only the beginning. The Navy and the Air Force have to take the necessary steps to prohibit structural discrimination against women as well.

Following the abolition of the tests, I was bombarded by messaged from friends who could not believe it had finally be done. My friend Marel, after years of minimal contact, sent me a message about the abolition of the tests. The brief celebration was followed by the hesitance we women have all been trained to have. Will the change actually happen?

Editor: Evi Mariani

Faye Simanjuntak is a second-year university student who has spent more than eight years working to eradicate child trafficking, exploitation and abuse in Indonesia through long-term, grassroots programs at Rumah Faye. She also works to facilitate discussions of Indonesian sociopolitics through What Is Up, Indonesia? (WIUI)⁷ on Instagram. The author would like to thank Jordinna Joaquín for her help with this article.