In Wamena, the city at the economic center of Papua’s central highlands, a mother of two stays home to avoid contracting Covid-19. The woman who asked to be identified as AB reminds everyone–family or visitor alike–to wash their hands before entering. The number of coronavirus cases in Wamena has been increasing. Local officials suspended commercial flights to the region on July 12, in line with tighter restrictions imposed by the central government, far away in Jakarta, following a surge in deaths.

Unlike as in the first wave of Covid-19 infections in 2020, the second wave has affected people close to AB. Two of her neighbors were buried a few days earlier. Her own mother was hospitalized for a week. “When the first wave came […] they said Papuans couldn’t get it, but the second wave actually killed a lot of Papuans,” AB said in a phone interview.

Unfortunately, according to AB, people have lowered their guard against the pandemic, as seen in her observations of daily life in Wamena.

No one in her family has been vaccinated. Information on social media about the vaccine’s side effects has made her doubtful. Moreover, AB and her husband suffer from HIV and are following a treatment program.

“Personally, I don’t really mind [a vaccination]. What makes us hesitant is all the information on whether the vaccine is good or not, its side effects and everything. And people like me–with a comorbidity? This is the question. It’s better not to be vaccinated because of the fear of fatal side effects.”

AB said that her only source of information about Covid-19 and vaccines is social media. Wamena’s slow internet makes finding accurate information a lengthy and expensive process. A local police car is the only source of direct information, when it announces mass vaccinations in the area.

“The average person here is terrified by the [possible] effects of the vaccine,” she said. “I’ve not seen any widespread explanation about the various vaccines that have reached this small community. I hardly know anything myself. Which groups need vaccines? We must know beforehand, right? So that we can decide what to do.”

AB said most of her unvaccinated friends were also worried about side effects. “This is closely related to them being unsure of their own medical history–a common story in Papua. When they fall sick, indigenous Papuans rarely go to puskesmas [community health care centers] but often treat themselves at home.” Access difficulties and Papua’s difficult geography have led to the province’s poor performance on the Indonesian government’s public health development index, according to the Health Ministry.

In Jayapura, the provincial capital, health care is far better than in other parts of Papua. Yet even here, residents have been increasingly burdened by the pandemic.

The head of the Papua Provincial Health Agency, Dr. Robby Kayame, said upwards of 20 people have died every day in Jayapura alone in July.

“Compared to March 2020, there has been a 300 to 400 percent increase in Covid-19 patients in March 2021,” Dr. Kayame said. “Every day, there are 150 to 400 cases.” This figure, he added, was based on people asking to be tested, not from testing requests from the officials tracing the close contacts of Covid-19 patients.

“If we look at the Papuan community, the number [of Covid-19 cases] might be double. It could be up to 60,000 or even more,” Dr. Kayame said.

Dr. Kayame sounded desperate when he said that funds, facilities and health workers in Papua were severely limited. In addition, Papuans are vulnerable to malaria, HIV, hepatitis and several other diseases that worsen their health. Poor nutrition and dietary habits also pose problems.

Since mid-July, almost every hospital in Jayapura has been overwhelmed with Covid-19 patients, such as Yoram Dwa, who fell ill on July 9. On July 20, his family took Yoram, who also had lung problems, to Yowari Hospital in Sentani, Jayapura, where he was diagnosed with Covid-19. Hospital staff wanted to transfer him to an isolation room but his family refused.

“We checked the isolation room, but the room was cluttered,” said Ambokari, Yoram’s wife. “How could the patients breathe fresh air?” When the family brought him home, his condition worsened. Yoram could barely breathe. Speaking tightened his chest. His oxygen saturation dropped to 50 percent, well below 94 percent, the level requiring immediate medical treatment, according to the World Health Organization.

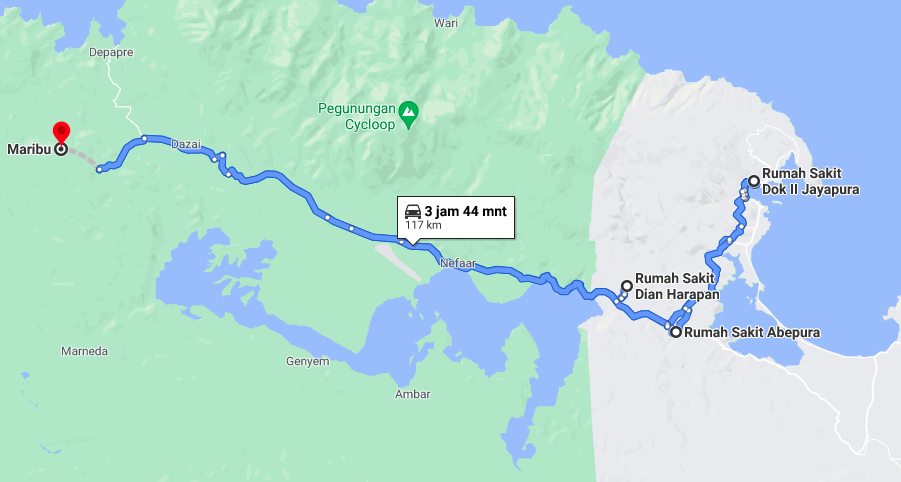

Again, Yoram’s family went to the hospital. However, by this time, Jayapura was in the middle of an outbreak. Beds were full, oxygen was scarce, and many local health care workers had been exposed to the virus. On July 25, the family went to Dian Harapan Hospital in Wamena. When there were no available beds, a nurse suggested going to Dok II Regional General Hospital–a larger, referral facility that also turned out to be overflowing with patients, as was the next facility on the family’s list, Abepura Hospital.

When Yoram’s breathing worsened as the car jolted along the rocky road, the family decided to take him back home to Maribu, in West Sentani. They had traveled more than 117 kilometers.

His condition now critical, Yoram was cared for at home, surviving only with an oxygen can purchased at a pharmacy. Someone from the local health center would occasionally bring medicine and offer advice on how to improve his breathing. Family and friends were trying constantly to get an oxygen cylinder with a regulator.

“Now we are busy looking for a way to get oxygen,” Ambokari said. “If we cannot get it in the next few days, then we’ll just use whatever we have, because of the crisis.”

I observed the hospitals where Yoram’s family had sought help. At Dok II, patients filled the veranda of the emergency unit, whose 15 beds were occupied with patients breathing with the help of supplemental oxygen or family members. At Abepura Hospital, patients continued to arrive, standing in line to be treated in the ER, while others waited for the bodies of their deceased relatives to be released by staff. One patient died before treatment.

The Trauma of Indigenous Papuans

The hospital crisis has coincided with low vaccination rates in Papua, especially among indigenous Papuans.

Efforts to overcome the problem have included a webinar, titled “Questions about the Covid-19 Vaccine”, held by the Jubi news outlet and Kingmi Church–two of the most trusted institutions in Papua–on July 24.

At the seminar, Dr. Kayame, the Papua Health Agency chief, said only 190,723 people in Papua province (13.06% of the population) had received one dose of the vaccine as of July 24, while second doses had been registered to 12,911 people (5.58%).

Jayapura, Mimika and Merauke are all areas of Papua with higher vaccination rates than the mountainous areas of Lapago and Meepago. In Saireri area, the vaccination rate in Biak regency is much higher than in Supiori, Yapen and Waropen. Vaccination rates in Boven, Mappi and Asmat are in the higher range.

“The percentage of Papuans who have been vaccinated is very small compared to non-Papuans in some places,” Dr. Kayame said.

Many believe since Papuans continue to gather with little regard to the virus, that they cannot be infected with Covid-19, according to Dr. Kayame. This misbelief has been exacerbated by hoaxes on social media, including WhatsApp, that have spread fear-mongering narratives about the vaccine’s potential side effects.

Distrust of the Indonesian government is another factor for Papuans who refuse to be vaccinated, according to Rev. Benny Giay, leader of the Kingmi Church in Tanah Papua.

The experience of the Papuan people with the Indonesian state has been one of murder, repression, imprisonment, fear and trauma. For the past two years, Covid-19 has been used an excuse for Indonesian security forces to silence Papuan voices protesting against racism and Jakarta’s interests, Rev. Giay said.

“Those suspected [of abuses] by the Papuan people should not be involved in overseeing vaccinations,” said Rev. Giay. The involvement of the Indonesian Army and police in vaccinations has made Papuans hesitant to get the injection, he added.

Audryne Karma, the daughter of the political figure Filep Karma, said Papuan distrust of the government went beyond vaccines, stating that local indigenous Papuans were already afraid that pre-pandemic public health programs had a hidden agenda.

“We have ingrained trauma,” she said.

Audryne, who as a dentist worked for three years in Dekai, Yahukimo, said that the local child mortality rate in the region was high, since the community objected to basic immunization programs. A widespread polio outbreak in 2019 prompted the government to launch another vaccination campaign that succeeded only after health workers collaborated with the local church.

Vaccine hesitancy also stemmed from a lack of official information, Audryne said. “I think it’s everyone’s right to know the side effects of drugs and whether they are harmful or not. But I don’t see that. I only see the information from the WHO that provides detailed facts on the vaccine’s side effects.”

Eben Kirskey, a US anthropologist who has researched Papua, has urged Papuans not to fear vaccination. He shares similar suspicions related to the movement “Papuan Lives Matter”, which echoed “Black Lives Matter” with shared experiences of racism. Suspicion among black Americans, he said, was quickly eroded when people became aware of Kizzmekia Corbett, an African-American who was the key scientist behind the development of a Covid-19 vaccine.

“If you are young, under 30s or 40s, if you don’t feel sick, I think it’s better to use Sinovac. However, if you are over 70, diabetic, a bit overweight, and have a heart disease, which means you have a high risk of dying from COVID-19, Astra Zeneca may be more suitable,” said Kirksey.

“The logic is, if you have a medical condition, you must get vaccinated sooner because you’re more vulnerable when exposed to Covid-19.”

Melissa Hascatri, a physician who leads the Yoka puskesmas in Heram, Jayapura, said that most of the people seeking vaccinations at her center came from outside the village. “We still have to continue to approach locals. They want to access information [on vaccines and Covid-19]. In the beginning [of the pandemic], we were still spreading information, but people also said they had heard of some hoaxes,” Melissa said.

The number of Covid-19 cases in her area has increased. In July 2021, 14 to 16 patients were positive for the coronavirus. Half the clinic staff tested positive, including Melissa. One of her staff was transferred to Dok II for treatment.

Melissa said more information campaigns with community leaders are needed to convince Papuans to be vaccinated. “We have already sent a letter to the church. We will definitely communicate with the church again.”

‘My Mama Drinks Eucalyptus Oil’

The last two months have been tough for Rev. Samuel Hesegem, a pastor at the Indonesian Christian Church (GKI) in Papua. He lost his parents, Alex Hesegem, 65, and Amelia Infandi, 53, to Covid-19. They died at Dok II Regional General Hospital.

His father, who was Papua’s deputy governor from 2006 to 2011, died on June 20, following treatment in isolation for three days. Three weeks later, his wife died after a night in intensive care.

Samuel was the first in the family to test positive, after a few days of fevers and shortness of breath. He said that he felt strong enough to self-isolate in a room on the second floor of their house. But his parents continued to interact with him.

“I reminded them ‘I’m positive. You should stop at the door.’ But […] you know how parents are.”

“Mother always wore a mask. Father too. But sometimes at night when I was asleep, he came in alone, with no mask, he sang, he prayed for me, even though I always reminded him.”

The family doctor suggested that Samuel’s parents and the relatives who had interacted with him take a swab test. His father tested positive and his mother tested negative. Samuel said his father was distressed: X-rays revealed spots on his lungs. The physician recommended antiviral medicine and other drugs for his stomach and lungs. Alex previously suffered from complications, including stomach pains.

“I was also given lung medication and antivirals,” said Samuel. ”I think it was this part–the reaction from the medication–that led to Papa feeling immediately weaker and he had to be rushed to the hospital.”

Samuel continued to have breathing difficulties and was treated at the same hospital.

“It was when I was isolated that Papa passed away. I only heard the news. It was hard, as I was dealing with the coronavirus and I lost Papa. I wished I could see him one last time, but the doctor wouldn’t allow me with my chest feeling so tight.”

While Samuel was in the hospital, his mother stayed close by. He improved and Samuel and his mother were tested on July 2, when Samuel was released. His mother, however, tested positive. They received the results on July 4.

“Mama heard drinking eucalyptus oil was good for [Covid-19] patients–three to four times a day. Eucalyptus oil is diluted in warm water. Mama was probably so desperate that she took eucalyptus oil directly from a spoon and downed it with warm water. But she had stomach problems and had immediate reactions when she took it,” he said.

Samuel decided his mother should isolate at home. However her condition remained poor and on July 11 she was rushed to Dok II General Hospital–again, at the height of the recent spike in Jayapura. Amelia waited in a wheelchair for hours before she was given a bed.

“Mama was panting and sweating for almost half an hour. They were late to change the oxygen tank. Even when they changed the tank I saw her oxygen saturation had decreased to around 70, Samuel said. “In the ER, we could only say, ‘Mama you must be strong. We only have Mama, you must be strong.’”

The doctor took Samuel’s mom to intensive care. She died on July 13.

Politics Complicate the Pandemic

In the last two months, politics in Papua have been driven by the Jakarta elite. It has been hard for the provincial to focus on the pandemic.

At the end of June, Home Affairs Minister Tito Karnavian, a former National Police chief and former chief of the Papua Provincial Police, appointed a local bureaucrat–without notice–to fill in for Papua Governor Lukas Enembe, who was sick. This angered Enembe, who threatened to report Tito to President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo. Papua hasn’t had a deputy governor since Klement Tinal died in May.

Divisive politics continued in July, when the House of Representatives in Jakarta passed a revised Papua Special Autonomy Law over local protests, with provisions authorizing the province’s expansion without consulting the local legislature. Police arrested dozens of demonstrators in Jayapura, charging members of the crowd with violating health protocols.

Tito also vacated Enembe’s plan, devised after experts said the Delta variant entered Papua, to close sea and air access to the province from Aug.1 to Aug. 31. Jakarta did not want a lockdown. President Jokowi previously approved extended lockdowns only for Java and Bali. Tug-of-wars between the central and local governments have been common since the pandemic took hold in Indonesia in 2020.

Unlike other Indonesians, Papuans are used to the sight of security forces into areas regarded as hotbeds of armed resistance. Jokowi’s government has labeled political groups demanding a referendum on Papua’s future as terrorists. Recalling the example of East Timor, which gained its independence after an Indonesian invasion through a referendum, activists have called for a similar vote in Papua.

Jokowi’s security approach, continuing from earlier regimes, has aggravated problems in Papua. Favouring an economy-first approach to the pandemic, Jokowi has not implemented the full provisions of the Health Quarantine Law, which was intended for emergencies such as pandemics. It is a move that would require the government to meet all the basic needs of the people during a crisis like Covid-19.

Despite the pandemic, the central and provincial governments are planning to hold the 20th National Sports Week (PON XX) in Papua in early October.

“Everyone should be responsible. All these Papuans are dying. The virus has spread everywhere throughout Papua, up to the remote hinterlands,” Dr. Kayame said.

Rev. Giay urged the establishment of a special team comprising representatives of churches, civil society organizations and the media to monitor the vaccination program in the province.

“We need a new step–a new concept–to enable a program that we can promote. A team that we can trust, so that we can break down the wall of distrust that is deeply ingrained in Papuan society. If this team is not accepted, it will amount to suicide. Papuans will die […] and become extinct.”

Editor: Fahri Salam, Ati Nurbaiti, Christian Razukas

This article is part of the #KamiSesakNapas and #DiabaikanNegara reporting series supported by Yayasan Kurawal.

This article is originally published in Indonesian as part of the report series to portray inequality in Covid-19 handling. The series is supported by Kurawal Foundation. You can help Indonesia deal with oxygen shortage through #OxygenForIndonesia.

Translated from Indonesian by Maria Clara Yubilea Sidharta – AIYA translation team.