Some 60,000 people have been displaced by fighting between Papuan separatists and the Indonesian military in Nduga Regency. One group of refugees are stranded far from home, without jobs, schools, quality healthcare or any sign of the conflict’s end.

EVERY December, Raga Kogoya’s memory returns to the tragic morning in late 2018 when her hometown became a battleground. It has been more than three years since the 42-year-old teacher and the rest of her community were expelled from their village—years she says have been the darkest of her life.

Most mornings in Nitkuri Village, in Papua’s Nduga Regency, used to begin with residents going out to work in the fields or into the forests to forage food. But one day in early December 2018, instead of waking up to soft morning sunlight, they were jolted awake by the roar of a helicopter propeller overhead and the scent of smoke billowing around them.

Raga awoke to the screams of her brother and neighbours. She bolted outside and saw people running in a panic. Looking up, she saw Molotov cocktails falling from the helicopter onto the village. Flames engulfed the villagers’ homes, gardens and fields.

Gunshots rang out as Raga woke her two children—around 6 and 8 years old at the time—who had slept through the commotion. She carried them as she fled the village in search of safety.

“People were running, scared as hell,” she says. “We forgot everything. Money, children, wives, sick parents—many were left behind, because the first thing we had to save was our lives.”Click To TweetThe Indonesian military’s attack on Nitkuri and several other villages in the area came two days after the “Nduga massacre”, in which the separatist West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) abducted 24 workers who were building bridges for the state-owned construction company Istaka Karya on 1 December 2018 and executed at least 17 of them the following day. TPNPB—which the Indonesian government designated a terrorist organisation last year—claimed the workers were Indonesian military personnel disguised as civilians.

Many Papuans support West Papua’s independence from Indonesia and view the ongoing Jakarta-backed infrastructure drive in the area as an effort to colonise their land.

In response to the massacre, Indonesian president Joko “Jokowi” Widodo declared a state of emergency in Nduga and authorised a joint military and police operation known as Operation Nemangkawi, aimed at tracking down separatist rebels in the area.

As of November 2021, around 60,000 people have been displaced by the ongoing fighting between Papuan separatists and government forces in Nduga Regency and surrounding areas, according to the Papuan Council of Churches, a coalition of Christian churches and associations.

“Our lives have become more difficult since the war continues. We don’t know when this will end,” Raga says. “The cost of [war] is so high. We [civilians] are the victims. It is not clear how long we have to endure being refugees.”

Raga is one of more than 500 displaced people living in Sekom Village, in Wamena District, about 85 kilometres from Nitkuri Village. They live in communal thatch-roofed homes known as honai that house up to 18 people each, some sharing with locals and others in an area of the village designated for refugees. Many of the refugees fled their homes without their government-issued identity cards and cannot seek formal work.

In late 2020, Raga’s younger brother and uncle travelled back to Nduga to retrieve important documents and belongings they had left at home. The morning they arrived in Nitkuri Village, Indonesian troops shot them dead. The military later claimed the two men were members of an “armed criminal group”, referring to a Papuan separatist group, and that they were carrying guns. Raga received a message from a relative saying her brother’s body was found in the yard of their house in the village.

“My brother died in our yard with a fractured skull and a splattered brain,” she says, adding that his body was left alone for several days because no one dared approach it for fear of being shot.

She adds: “I know they didn’t have guns or rifles. They carried machetes to cut down plants that got in the way.”

Recalling how she was unable to provide her brother and uncle with a proper burial on their ancestral land, Raga breaks into tears.

“They were put down and left to die like animals,” she says.

Health Crisis

On Christmas Eve 2022, Raga’s younger son King leads a group of visitors on an hour-long trek from the highway in Muliama District towards a plume of smoke in the distance marking the location of Sekom Village. The terrain is muddy and rocky.

“You have to be careful, okay? Because we never know what is at the bottom of the puddle. It could be a snake or another venomous animal. If you’re lucky, it might just swell if it bites your leg. If you get bad luck, ouch, the hospital is far away,” says King, who is around 12 years old.

The walk from Sekom to the nearest hospital in Wamena can take more than 24 hours, and those who are lucky enough to secure a car ride can only get there in three hours.

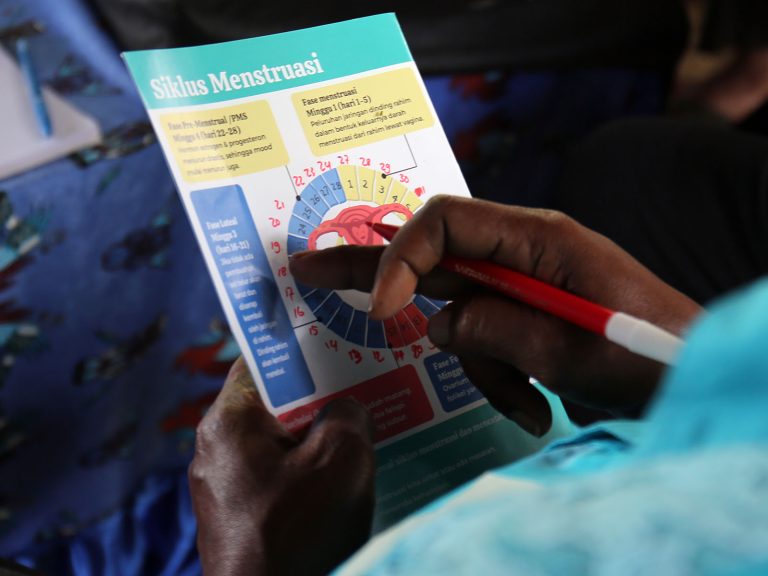

But distance is not the only obstacle. Without their government-issued IDs, many of the displaced villagers cannot access public health services. Many now rely primarily on traditional medicine, using plants from the forest.

“We thought our fate would be far from danger when we left Nduga. But in fact, it’s not. In the refugee camps, our lives are getting more difficult,” says Raga, who serves as an informal coordinator for the displaced people in Sekom Village.

According to Raga, around 30 refugees have died in the village because they could not get the medical treatment they needed in time. Over the last three years, health workers visited several times to offer the refugees’ medical care, “but they came at the wrong time”, she says. “It was always too late. They only come when the sick are dead.”

She adds that most of the deceased have been women and children, largely because there are no facilities, doctors or midwives to ensure safe childbirths. Many times, she says, a mother and her unborn child have died at the same time.

“Some of the women here give birth at home. But that is only if the host of the place we’re living with agrees. If not, then we give birth in the forest, in a cave, in the river in search of running water. Because if the [local] homeowners are angry, they can kick us out at any time,” Raga says.

School Disbanded

Before settling in Sekom Village, some of the people displaced from Nduga took refuge in the courtyard of Wamena’s Weneroma Church, where they set up a makeshift “emergency school” for their children. Raga, one of the few members of the community with a university degree, volunteered as a teacher. Although the school was poorly equipped, with just one blackboard and a few boxes of chalk, Raga believed the education she provided would help ensure a brighter future for the children.

But in early 2020, the Indonesian military came to the church and asked the students to disperse. Raga’s son King says the sight of the soldiers in the churchyard terrified him and reminded him of the morning in late 2018 when he woke up to his village being destroyed.

“Children get scared every time they see soldiers. The soldiers just arrived at the churchyard, and the children immediately ran away in fear. Trauma is so imprinted in their heads,” Raga says.Click To TweetIn 1996, the Indonesian military launched an operation in Nduga Recency’s Mapenduma District to rescue 11 members of a World Wildlife Fund research mission who were taken captive by the separatist Free Papua Movement. Eight separatist fighters and two hostages were killed in the operation, which was led by Indonesia’s current defence minister Prabowo Subianto.

The operation forced many of Raga’s friends in the area to drop out of school. They are now parents to some of the children who studied briefly at Weneroma Church.

“That’s why I don’t want these children to have the same fate as their parents,” Raga says. “But that hope is gone now. The school was disbanded, and the children dropped out again. Their future suddenly seems dark again.”

No Return

Over the course of their stay in Sekom Village, the Nduga refugees have experienced intermittent hostility from the local population, causing them to live in fear of being expelled by their hosts.

“Even if we just take water that flows abundantly in the river, [locals] can get angry,” says Pastor Kones Kogoya, a Protestant leader from Nitkuri Village. “Can you imagine how these limitations restrain us?”

Kones says the refugees are also forced to accept low wages for working on locals’ fields, both because there are few other work opportunities and to foster goodwill among the people of Sekom Village. Some of the refugee workers have been given small plots of land to plant tubers for themselves.

But this goodwill can disappear in an instant. In mid-2021, a local woman was killed in a hit-and-run accident on the nearby Muliama District highway. Unable to catch the driver, many locals blamed the refugees. According to Kones, the chief of the local community demanded the refugees give locals 30 pigs, one motorbike and 200 million rupiah (US$14,000) in cash.

“We don’t know where to get so much money from,” he says. “As long as we are refugees, we cannot work. But if we refuse to pay, we will be evicted. So like it or not, we have to search for it.”

In December 2021, Kones went back to Nitkuri Village hoping to arrange for the rest of his community to eventually return. But after three weeks, he was forced to return to Sekom after both the Indonesian military and the TPNPB told him they were not responsible for his safety.

“The [separatists] say that before Papua can become independent, the war will continue. It could last until tomorrow, next month, next year or a few more years,” he says.

The pastor’s brief visit to Nduga made him realise that his home is no longer the same place it was when he grew up there. The roads, houses and yards have been overtaken by trees and weeds taller than a grown man. At night, the sound of crickets was pierced by gunshots.

“Nduga is no longer a pleasant area since the war broke out and took everything without a trace,” he says. “Only the goodness of God can bring us back home, though we don’t know yet when that day will come.”

Ongoing Violence

Theo Hesegem, executive director of the Papua Justice and Human Integrity Foundation, says that one way for refugees to return to Nduga would be if there were a ceasefire between the military and the separatists, but this would require a long dialogue that is unlikely to happen in the near future.

“The most expensive cost of this war is the psychological terror experienced by the people,” Theo says. “Death happens in a moment, but the wound felt by the families left behind—they will suffer for the rest of their lives.”

Theo’s organisation contributed research to a report from Nduga’s Humanitarian Evacuation Team, a watchdog group of Papuan intellectuals, which said 263 displaced people from Nduga died between 2018 and 2020. The causes varied; some died while trekking through the forest, others died of starvation or during childbirth, and some were shot by the Indonesian military.

He estimates that the death toll has risen past 500 since those findings were published.

“We presented the data at many human rights congresses. One of them was in Geneva. We are doing everything so that peace will come soon, and no more blood will be spilled on the land of Papua,” Theo says.

In February 2020, a team working for the Australia-based Indonesian human rights lawyer Veronica Koman submitted the names of 243 victims of the Papuan conflict to President Joko Widodo while he was visiting Canberra.

Mahfud MD, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, told Tempo the government had not officially received the data, and if it was among the many letters the president receives from ordinary people, it’s “rubbish”.

“Those they called ‘rubbish’ were someone’s family member, child, brother or friend,” Theo says. “Why [does the government] respond like that—like our people’s lives are meaningless in their eyes?”

Raga says as long as the Indonesian government continues to use the “language of violence”, there is no hope for the fighting to end. She recounts hearing children who have been forced to drop out of school pledge that when they grow up they will return to Nduga and take up arms against the government.

“I shudder at the thought of the grudges that are ingrained in these children,” she says. “One village elder said these children were born holding knives, and none of us know who will be stabbed—maybe those who killed their brothers.”

This article was supported by a fellowship from Indonesia’s Alliance of Independent Journalists. A version of this article also published in New Naratif.