Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati knows very well how to handle President Joko Widodo. It’s next to impossible to argue with the Indonesian leader once his mind is made up. So when the president–popularly known as Jokowi–says to do something, Sri Mulyani says yes first, and thinks about it later.

Sri Mulyani told this story at a farewell for Jokowi’s first batch of Cabinet ministers on Oct. 18, 2019 at the State Palace in Jakarta. After the event, journalists swarmed Sri Mulyani for doorstop interviews, asking about everything from the Finance Ministry’s plans for the president’s second term to her impressions of working under Jokowi.

The former World Bank managing director spoke highly of Jokowi, who she described as no “ivory tower” policymaker, but someone who wants to assess the situation on the ground and acts fast.

“When he wants us to fix things quickly, we must immediately say yes, even in the beginning. Because if we said ‘Oh, that’s impossible’, that would create a problem,” Sri Mulyani said. “We have to say ‘yes’ first, then we start analyzing the problem.”

Such leadership plays well with the general public, who want the government to work quickly, Sri Mulyani said. However, in reality, Jokowi’s rushed decisions have often been ill thought out and inefficient.

The president has a reputation for setting ambitious targets on tight deadlines. For instance, in Jokowi’s first five-year term, which ended in 2019, the istration was determined to get rid of the so-called oil and gas mafia in 2015, resolve seven cases of gross human rights violations in 2016, achieve 7% economic growth in 2017, acquire a majority stake of gold and copper miner PT Freeport Indonesia in 2018, and finish building new power plants worth 35 gigawatts (GW) in 2019.

Of the five examples, acquiring Freeport Indonesia was the only success. Jokowi’s habits of setting sky-high targets and favoring rapid execution have made a mess for Indonesia, including its energy sector.

From the get-go, Jokowi’s wanted to boost economic growth. By bolstering strategic domestic industries, Jokowi intended for Indonesia’s economy to grow by 5.8% and 6.6% in his first two years in office, and by 7.1%, 7.5%, and 8% in the last three years, according to the 2015-2019 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN). As a consequence, annual per-capita electricity consumption was also projected to surge, averaging 7.3% annual increases in the same period.

Anticipating this, Jokowi launched on May 4, 2015, the 35-GW electricity program, which called for 25 GW to come from coal-fired power plants. Estimates called for state utility firm PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) to obtain an additional 100 million tons of coal a year for the new plants.

Based on US Energy Information Administration (EIA) calculations, every million tons of coal burned emit 2.86 million to 3.17 million tons in carbon dioxide, meaning that Jokowi’s new coal plants would release an additional 300 million tons of carbon dioxide each year.

These projections for increased domestic electricity use and coal consumption led the government to review Indonesia’s long-term coal business. All the time, most of the coal mined in Indonesia was exported, prompting the government to start reserving a supply for future domestic use.

Officials came up with a plan to cap Indonesia’s annual coal production at 400 million tons and gradually reduce exports starting in 2019, aiming to cease exports if domestic consumption hit the cap.

As Indonesia’s commitment to coal grew stronger, Jokowi simultaneously wanted the country to contribute to global efforts to stop climate change. Indonesia ratified the Paris Agreement, an international treaty adopted at the end of 2015 with the objective of limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius.

Jokowi aimed for Indonesia to cut by 2030 its greenhouse gas emissions in the energy sector by 29% independently, or by 41% with international assistance, from the 2010 level. To do so, he planned to increase the share of new and renewable energy in the national energy mix from 5% in 2015 to 23% in 2025 and then 25% in 2030.

To be sure, Indonesia is rich in clean energy resources. The nation’s renewable energy potential tops 442 GW, according to the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry. Solar power comprises the biggest potential contribution, at 207.9 GW.

However, the nation has been struggling to get the most out of its renewables. Instead of making good on promises to be a clean energy producer, the country is currently one of the world’s largest carbon emitters.

In 2015, Indonesia’s installed power plant capacity stood at 55.5 GW, 49% of which came from coal and about 12% from renewables. At that time, the energy sector comprised 22.6% of Indonesia’s annual greenhouse gas emissions of 2.37 billion tons of CO2 equivalent, according to the Environment and Forestry Ministry. The largest emissions sources were peat fires (33.8%) and forestry and other land uses (32.3%).

“As one of the biggest rainforest countries, which serve as the lungs of the Earth, Indonesia has chosen to be part of the [climate crisis] solution,” said Jokowi during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, France, on Nov. 30, 2015–just seven months after he launched the 35-GW power program.

Ambitions Without Results

Jokowi’s ambitions were the basis for the government’s long-term national energy policy. In 2017, Indonesia introduced its General Plan for National Energy (RUEN), which outlined the nation’s energy needs through 2050.

RUEN projections were based on several key assumptions about economic growth, population increase, renewable energy potential, and projected electricity consumption. It estimated that the capacity of Indonesia’s new and renewable energy power plants would jump from 8.6 GW in 2015 to 45.2 GW in 2025 and to 69.7 GW in 2030.

PLN, the state-owned electricity firm, translated the grand design into its electricity procurement plan (RUPTL). The document, published annually, contains a complete list of power plants to be built in the next decade.

At the end of the day, Jokowi’s grand vision was a house of cards. If any one element buckled, the tower would come crashing down–and that is what happened.

Between 2015 and 2019, Indonesia’s annual economic growth averaged 5.03%–far short of a projected 7%–while annual per-capita electricity consumption grew 4.3%, well below initial estimates of 7.3%.

By the end of 2019, the nation’s total installed power plant capacity was 69.6 GW, including 42.3 GW from PLN. In the same year, the national electricity supply was 278.5 terawatt hours (TWh), versus electricity consumption of 289.3 TWh.

The 35-GW program was running behind. Up to 2019, only 14% of the plants covered by the program had started commercial operations, 62% were under construction, contracts were awarded for 20%, and the rest were stuck in the planning and procurement phase.

Sluggish progress only delayed the inevitable: a huge electricity oversupply. Since consumption was below expectations, the new power plants from the 35-GW program would bloat PLN’s reserve margin and increase its electricity generation costs.

Domestic coal consumption also fell short, leading the government to backpedal on its planned caps. Coal production soared to 610 million tons in 2019, despite an initiative to implement a 400-million-ton limit, as the government wanted to boost coal export revenues and ease a trade deficit.

Renewable energy development then stalled. PLN was exhausted by its race to build renewable power plants, as it had to bear a huge debt burden to build infrastructure and maintain electricity rates while coal prices fluctuated. The last point is crucial as about half of Indonesia’s power facilities use coal, which means that higher prices lead to higher operational costs.

Meanwhile, independent power producers (IPP) have been reluctant to invest in renewables due to policies that make it difficult to obtain soft loans from lenders. The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry’s Regulation No. 50/2017, for instance, caps renewable electricity rates at 85% of local generation costs (BPP), if such costs exceed the national average.

As a result, Indonesia’s renewables capacity was only 10.1 GW in 2019, while coal came in at 34.7 GW. With the renewables share of the energy mix stuck at 9.15%, the energy sector produced 34% of the 1.8 billion tons of CO2 equivalent that Indonesia emitted in 2019.

Then Covid-19 appeared, complicating things even more.

Catch-22

The pandemic hit Indonesia hard. The national GDP contracted 2.07% in 2020. Manufacturing and household consumption–the biggest contributors in terms of production and expenditures–shrank by 2.93% and 2.63% respectively.

Unsurprisingly, per-capita electricity consumption grew by a scant 0.46% to 1,089 kilowatt hours (kWh). The problem was that new power plants continued to be built. National power generation capacity increased by 4.4% to 72.7 GW in 2020, despite stagnant demand.

PLN couldn’t cancel the ongoing power projects and had to persevere, despite an electricity oversupply and its mounting debts—increasing by 64.8% to Rp649.2 trillion between 2016 and 2020.

The state-owned company claimed that it could only focus on building renewable facilities after it finished Jokowi’s 35-GW program-and the fast-track programs (FTP) devised by Jokowi’s predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was in office from 2004 to 2014. Dozens of FTP projects have been in limbo–for a multitude of reasons. Only some of them are set to resume.

With burdens weighing on its shoulders, PLN came to the State Palace on May 11, 2021, in answer to a summons from Jokowi. The president ordered PLN to stop developing new coal-fired power plants. Work already underway could continue, as well as any financed project not yet begun. Ministry and agency bigwigs were also requested to come up with a legal umbrella to support the new policy “should any problems related to legal aspects arise,” said PLN Corporate Planning Director Evy Haryadi.

That order was aligned with the government’s then-efforts to formulate a long-term strategy for Indonesia to achieve net zero carbon emissions. Other countries, including China, Japan, and South Korea, had previously announced their zero-emission plans and Jokowi wanted to follow suit.

Hence, in July, Indonesia submitted its updated climate commitments to the UN and set a deadline to eliminate completely its greenhouse gas emissions by 2060 or before. This was part of national preparations for the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, in November.

The change in direction affected the drafting process of PLN’s new 10-year plan. The company now must take into account the electricity oversupply amid weakening demand, the obligation to provide affordable electricity, the completion of Yudhoyono and Jokowi’s big power projects, the target of increasing renewable energy share in the national energy mix to 23% by 2025, and the zero-emission goal in 2060.

As a result, PLN came up with a new draft for its next RUPTL, which the company claimed would be its first “green procurement plan” ever.

The draft contained significant adjustments to its national electricity consumption projections. In the previous plan, which covered 2019 to 2028 and was issued before the coronavirus outbreak, PLN said that annual electricity demand would exceed 400 TWh in 2027. In the draft plan for 2021-2030 plan, PLN estimated that the figure would only reach 390 TWh by 2030.

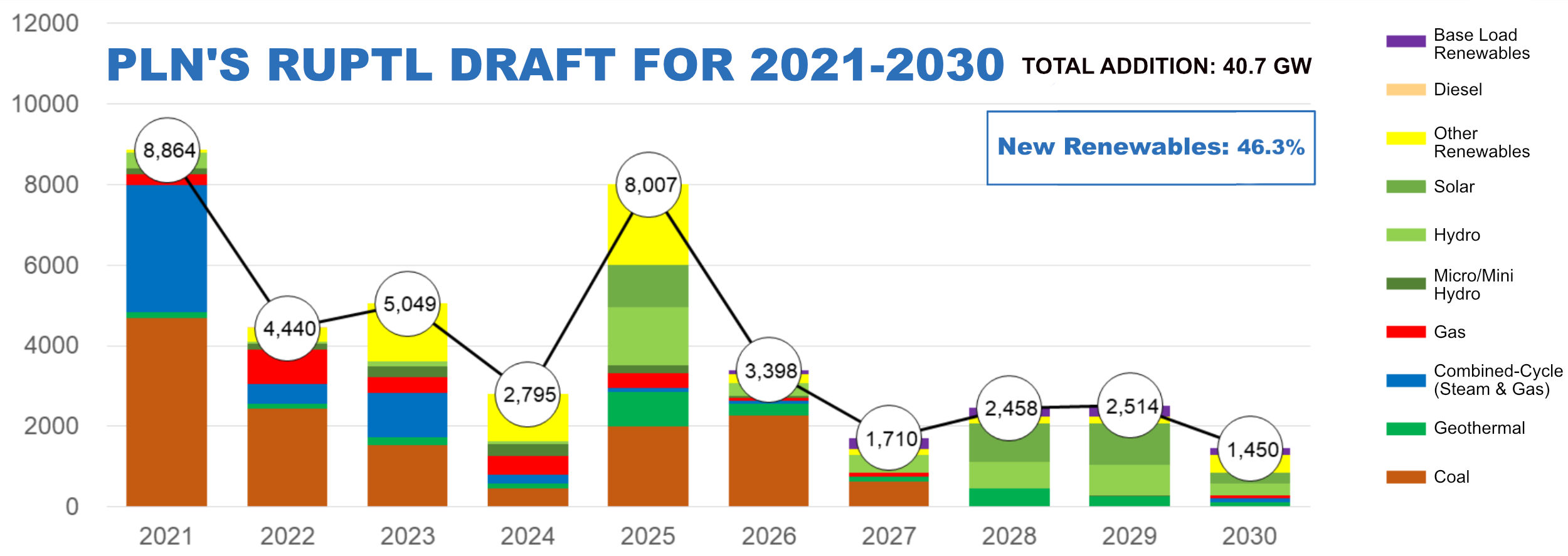

The state-owned firm had no choice save to reduce the number of power plants it planned to build over the next 10 years. It said that an additional 40.7 GW would come online by 2030, 46.3% of which would come from renewable plants. In comparison, the 2019-2028 plan called for an additional 56.4 GW with only 29.6% sourced from clean energy.

Meanwhile, ongoing coal power projects, including those from Jokowi’s 35-GW program and Yudhoyono’s FTP, would start operating between 2021 and 2027. After that, there would be no more new coal facilities.

No less importantly, PLN’s current draft plan projects that it would still meet its 23% renewable energy target by 2025. Meanwhile, Indonesia also expects to significantly cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 in line with the Paris Agreement.

How? By relying on coal-fired power plants.

Mulling over Shortcuts

Apart from attempting to develop more renewable facilities, PLN plans to use co-firing technology to burn coal and biomass simultaneously at a number of steam power plants. Biomass will be considered a renewable part of the national energy mix.

“The co-firing technology will be one of the solutions to ensure that the coal-based steam power plants can survive, while serving as a trade-off to achieve the 23% new and renewable energy proportion target in 2025,” Evy said.

The capacity of Indonesia’s coal plants reached 36.7 GW in 2020, while renewables merely stood at 10.46 GW.

PLN aims to use biomass to replace an average of 10% of the coal used in steam power stations in Java and Bali, and 20% for stations elsewhere in the nation.

As of July, PLN has run trials for the technology at 32 coal-fired plants, which will increase to 52 locations in 2025. Assuming the capacity factor stands at 70%, biomass used by those coal facilities is expected to generate 2.7 GW of electricity. Capacity factor is the ratio of the total actual energy produced by a power plant to its maximum generation capacity.

The problem is that PLN will need about eight to 14 million tons of biomass a year to realize its plan. Building a stable biomass supply chain over the long run is no easy feat. Biomass is expensive, and PLN will need even more investment to increase the proportion of biomass it intends to use at steam power plants.

“The biomass industry is a policy-reliant industry with high uncertainty,” said Putra Adhiguna, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). “In the absence of significant [government] incentives, it’s impossible not to question whether PLN will be able to deliver co-firing without encountering technical and financial barriers.”

Even the US and China–both of which possess abundant biomass potential, a large network of coal-fired power plants, and superior technology–have not succeeded in developing sizable co-firing operations, according to Putra. Meanwhile, the UK’s largest biomass power plant needed more than £700 million in public funding support just in 2019.

Another issue for PLN is how to source biomass. Through a deal inked in mid-July, state forestry firm Perhutani and state plantation holding firm Perkebunan Nusantara were committed to respectively supplying PLN with sawdust and empty palm oil fruit bunches for the latter’s co-firing operations.

Indonesia is infamous as a country with one of the highest deforestation rates in the world. It lost 465,500 hectares of forests and replanted just 3,100 hectares from mid-2018 to mid-2019, according to official data. The nation claimed it was able to significantly reduce deforestation during the pandemic, as it lost “only” 119,100 hectares of forests in the 2019-2020 period. At the same time, reforestation covered 3,600 hectares.

Using biomass from timber and palm oil processing without proper reforestation only perpetuates Indonesia’s environmental mess and calls into question the green credentials of biomass.

However, the government and the PLN do not have many choices. For the time being, it seems like they are desperate enough to turn questionable proposals into championed solutions.

If (and it is a big if) Indonesia succeeds in boosting renewable energy to 23% of its energy mix by 2025, then the government will have about five years to bring down the national greenhouse gas emissions. For this, it pinned its hope to battery-based electric vehicles.

Indonesia aims to have at least two million electric cars and 13 million electric motorbikes on the road by 2030, including those produced by local manufacturers. That way, it expects to stop fossil fuel and liquefied petroleum gas imports, while cutting emissions by 29%.

To do this, the government plans to build about 31,000 charging stations (SPKLU) for cars and around 67,000 battery-swap stations (SPBKLU) for motorbikes by 2030. About 113 million kWh in battery capacity will be needed. Where will the energy come from? Coal-fired plants, of course.

“Should we wait before electricity becomes totally clean before we can operate the electric cars? Currently, we’re working on both in parallel,” said Dadan Kusdiana, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry’s renewable energy director general, during a webinar in February. “Electric cars are still more environmentally friendly, even though 65% of the electricity will come from coal.”

Globally, scientists are still debating whether electric cars powered by fossil fuels are cleaner than cars burning gasoline directly.

In the end, Indonesia returns to coal to solve its energy issues-and for the sake of Jokowi’s grand dreams come true, even dirty energy is made “renewable”.

The Long Road to 2060

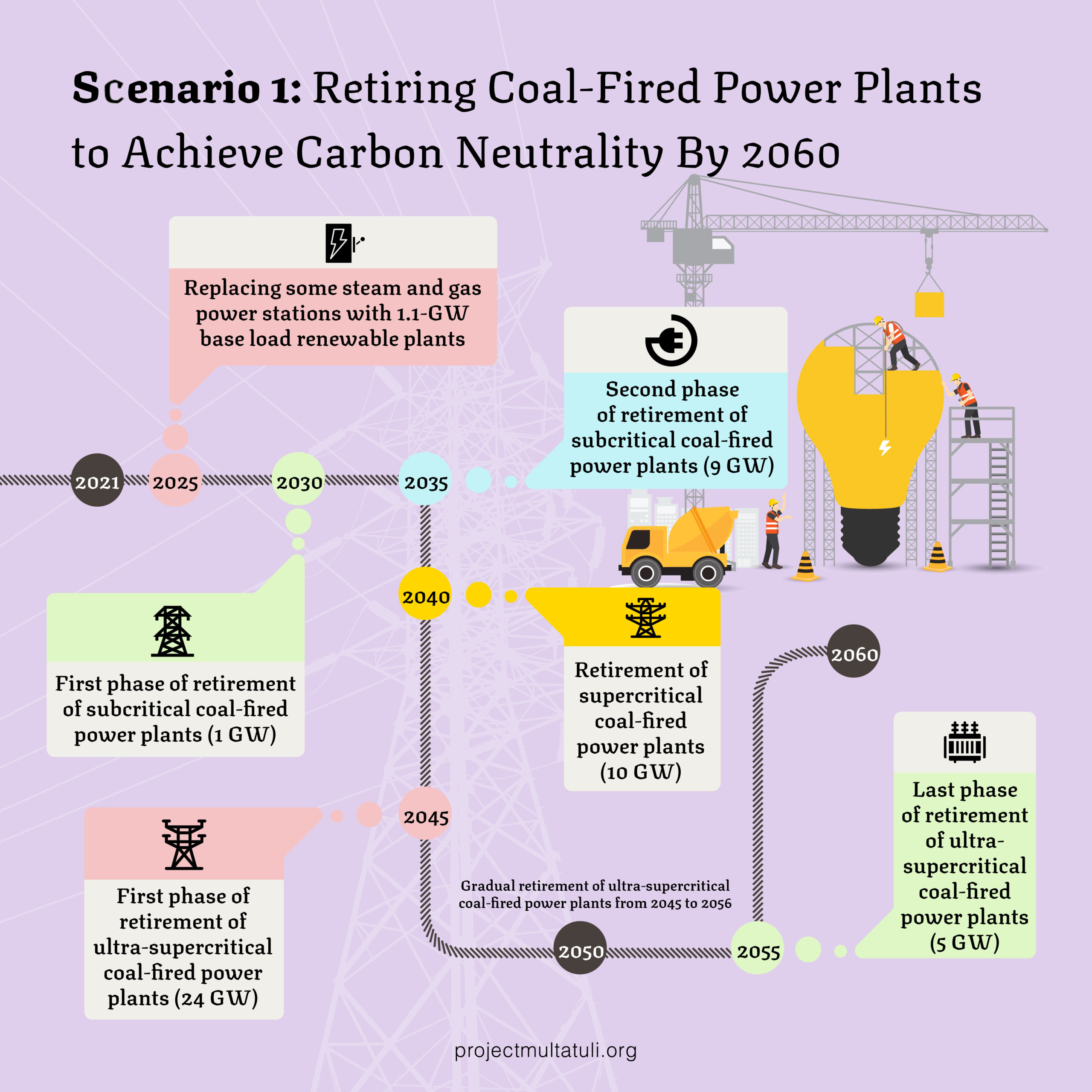

PLN has two scenarios for attaining zero emissions by 2060. The first includes retiring all its steam power plants. The second still pins lots of hope on coal.

The first scenario hinges on development of affordable energy storage tech so PLN can ensure a stable electricity supply from renewables. Solar power, for instance, is unstable since electricity production is disrupted by clouds or sunset. Solar needs storage to compensate for the disruptions.

PLN is banking on affordable energy storage tech so that it can replace some steam and gas power stations with 1.1 GW worth of base load renewables in 2025. PLN plans to retire coal-fired facilities, starting with subcritical plants between 2030 and 2035 period, moving to supercritical plants in 2040 and ultra-supercritical plants between 2045 and 2056.

“Coal [use] keeps declining,” Evy said. “In 2030, it will be only 59% [of all power generations]. In 2040, it will be 24%. Then it will go down to 11% [in 2045] and further down to 7% [in 2050], and finally 0% by 2060.”

Further, Evy states that nuclear power plants will come online in Indonesia 2040 “to maintain the reliability of the system in line with the development of nuclear technology, which will become safer.”

While several countries have started saying goodbye to nuclear power, Indonesia is just getting ready to welcome it. The 2014 National Energy Policy describes nuclear power as a last resort that can only be used by cautiously taking into account safety considerations. The top priority should remain to develop traditional new and renewable energy such as solar, hydro, or wind power.

Nevertheless, the inability to push renewable energy development amid ambitious plans to cut carbon emissions and phase out coal has led Indonesia to bet on nuclear power. The legal umbrella is now being prepared for it. Since 2020, lawmakers have been deliberating a draft bill on new and renewable energy, which will contain stipulations related to the use, business licensing and monitoring of nuclear power.

“Even if it produces low emissions, nuclear remains a high-risk activity,” stated the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law (ICEL) and Indonesia Cerah Foundation in a policy brief titled Two Crucial Issues Within the Draft Bill on New and Renewable Energy. “Indonesia, which is located within the Ring of Fire, or hotspots of tectonic plate activity–meaning that Indonesia has high risk of earthquakes and tsunamis–is not suitable for nuclear power plant development.”

Moving forward, PLN has pledged to keep developing traditional renewable power plants.

Still in the first scenario, electricity production is estimated to top 420 TWh once all the power plants from the 35-GW program go online. Meanwhile, electricity demand will amount to 1,800 TWh in 2060, meaning that the gap–1,380 TWh–will be closed by building new power stations capable of producing 250 GW, most of which will come from renewables.

PLN will require about US$500 billion in additional investment to meet its 2060 production goals. “PLN is not going to do it alone. We are going to do this through collaboration in terms of technology, in terms of investment, in terms of policy,” PLN Deputy President Director Darmawan Prasodjo said.

To increase investment in clean energy, the government has been drafting a presidential regulation for renewable electricity prices. It will include at least three schemes: a feed-in tariff, setting a highest benchmark price, and setting agreed-upon price. The goal is for renewable electricity to be more competitive so as to attract more investment.

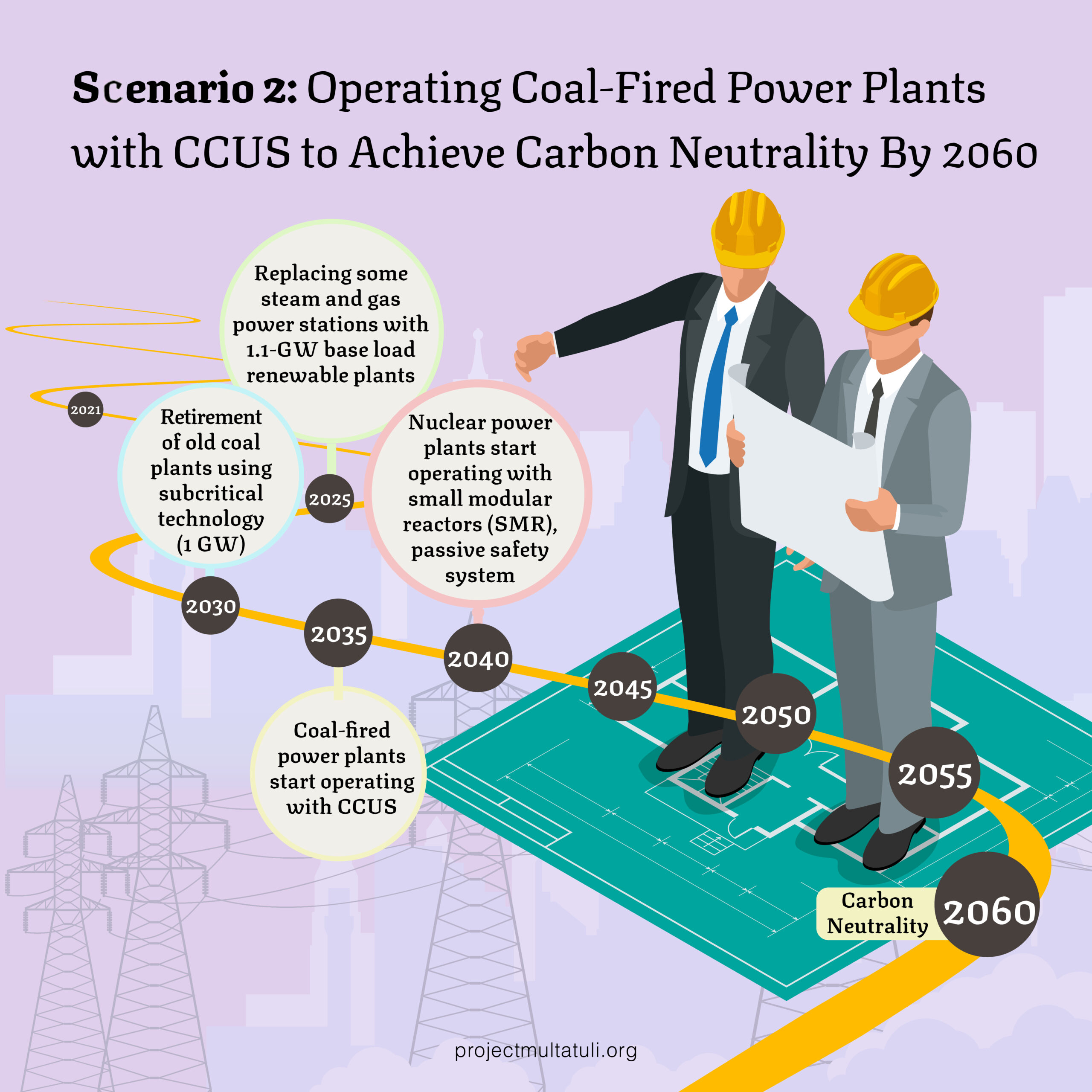

Meanwhile, PLN’s second scenario for meeting zero emissions by 2060 is, paradoxically, depending on coal. The firm is assuming that there will be innovations in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology to suck up carbon dioxide produced by fossil fuel power stations. Gases captured by CCUS tech can be used for several purposes, including boosting oil and gas production in mature fields.

In this scenario, PLN still plans to install base load renewable plants in 2025–but the only coal facilities slated for retirement by 2030 are the old, sub-critical plants with a 1-GW capacity. Other steam power stations will start operating using CCUS tech in 2035 and nuclear generators will be added to the firm’s system in 2040.

“Unfortunately, the current CCUS technology makes power plants derated by 30-40%. Thus, if a power plant capacity is 100%, its net generation capacity can only reach about 70%,” Evy said.

Moreover, another problem lies with the storage of dirty carbon, which is generally done in oil or gas fields that might not be close to the coal power stations. Hence, PLN will likely need to spend even more to install pipelines to transport the carbon from the plants to the storages.

The second scenario keeps the focus on coal’s crucial role in Indonesia’s electricity sector. Technological innovations will be used to extend the lifespan of dirty power plants. There won’t be many benefits in the long run, considering the global trend to protect the environment by using clean energy.

A report from research firm Carbon Tracker in June concluded that 92% of coal-fired power plants, with a total capacity of 300 GW, currently under construction in China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Vietnam, will not be economically viable to operate given advances in renewable energy. Moreover, in 2026, the operational costs of all the world’s steam power stations will be more expensive compared to developing new renewables, the report said.

“Based on this calculation, PLN’s coal-fired plants, with a capacity totaling 22.8 GW, will become stranded assets with a value amounting to US$15.4 billion,” said Fabby Tumiwa, the executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR). “Utility companies that operate various coal-fired plants must reconsider whether it is still cost effective to continue the operation of those coal facilities.”

The government seems to be aware of the problem. In July, PLN’s labor union leaked the government’s plan to transfer some of PLN’s steam-power plants to a new holding company. The assets to be transferred are old plants with a recorded capacity factor lower than 80% in the past five years and those with a figure set to drop to below 50% in the next five years. The new holding company is expected to seek fresh funds, including through an initial public offering, to support PLN’s future renewable energy development.

Fabby said such a plan was aligned with the idea of creating a coal retirement mechanism (CRM) to pave the way for developing countries to retire coal-fired plants early. According to Reuters, several global financial firms, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), HSBC, and Prudential, are currently drafting plans to make CRMs work through public-private partnerships.

Simply put, a CRM would acquire steam power plants across Asia and retire them within 15 years, much sooner than their typical lifespan of 30 to 40 years. Power plant owners could immediately get fresh funds to develop renewables and countries like Indonesia would find it easier to cut carbon emissions after retiring steam generators. Fifteen years is also enough time to give power plant workers time to find new jobs.

If PLN’s steam power stations were transferred to a new host, said Fabby, it would be much easier to conduct acquisitions via the CRM. At present, as reported by The Jakarta Post, PLN, ADB, and relevant stakeholders are conducting a pre-feasibility study.

This idea would offer a welcome bit of fresh air to Indonesia, which has for years consistently set numerous grand targets to develop its renewable energy potential, yet never shown the competence and courage to turn these targets into reality.

Risks are still plaguing Indonesia’s renewable energy sector, especially when Jokowi makes new policies without careful deliberation. With every sudden change in focus, it becomes harder to “just say yes” in the beginning.

Editors: Evi Mariani, Christian Razukas

Translators: Sebastian Partogi, Viriya Singgih

This article is part of the #EnergiKotor (#DirtyEnergy) reporting series supported by Earth Journalism Network through its special collaborative journalism project “Available But Not Needed,” which brings together six media outlets and more than a dozen reporters across seven countries to explore how public and private investments continue to fund fossil fuel economies in Southeast Asia.