In Indonesian public discourse, young people, in particular Generation Z, are described as well-educated, cultured, and tech-savvy, a generation producing the next wave of young, exciting start-up CEOs. Project Multatuli has looked into another Gen Z, one that is rarely talked about, the #UnderprivilegedGenZ: the poor, the queer, and the frustrated.

In 2022, a number of surveys described Generation Z, people born between 1996 and 2010, as well-educated, cultured, and tech-savvy. The Career Research Center of Andalas University and the Tanoto Foundation noted that members of Gen Z had high confidence in securing their dream jobs despite tough market competition.

Even President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo celebrated Gen Z as graduates of top universities who had enjoyed success at young ages. The generation was also described as spending their spare time hanging out at coffee shops and traveling for “healing”.

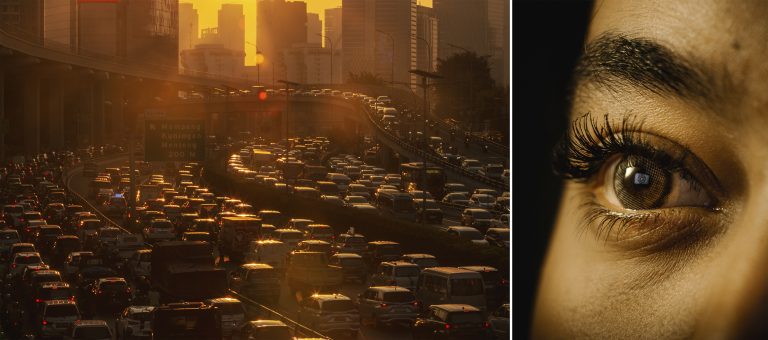

These picture-perfect characterizations may describe those born into privilege, but they do not capture the lives of the many members of Gen Z who were born into poor or struggling families. Statistics Indonesia data shows that in 2021, 3.8 million Indonesians aged 15 to 24, some 17 percent of the age group, were unemployed, and among 16- to 18-year-olds, some 21 percent had dropped out of school.

Many of these underprivileged members of Gen Z left school because of poverty, while others ran away from home because of family conflict. Life is tough for them as they struggle to earn their livelihoods without any family support while dealing with other personal concerns, such as with gender identity and mental health. Some have to financially support their parents, siblings, nieces and nephews.

Project Multatuli’s series #UnderprivilegedGenZ looks into the persistent, systematic problems many young people face. The following are synopses of the stories in English.

School Drop-Out, Child Laborer, then Sole Breadwinner

Berkat, 26, was born into a low-income family. His father was a truck assistant whose income alone was insufficient to support the family. Berkat dropped out of school when he was 12 years old to take a job and help make ends meet. He has been working ever since.

His first job was to pack pirated cassettes in Glodok, West Jakarta, for Rp 50,000 a day. Berkat then began juggling a second job as a transportation worker.

He worked for a time as a truck assistant earning Rp 150,000 per trip and was also once a contract worker for the so-called “orange squad”, a group of sanitation workers who fished piles of trash out of Jakarta’s polluted waterways. Now, after 14 years working, Berkat has managed to renovate his home and buy himself a motorbike.

When Project Multatuli met him, Berkat had just finished a one-day trial of a job where he lifted sacks of animal feed, each weighing 50 kilograms. He had chosen not to continue working there as he feared the consequences of an occupational injury. As the family’s sole breadwinner, Berkat did not know who would support his family if he was injured or fell sick.

He was looking for another job, but they were hard to come by because “everything uses technology”, an area that Berkat has had little exposure to.

Poor, Woke, and Having Mental Disorder

Anida, 23, lives in the heart of Jakarta. But unlike some of her Gen Z peers, she never hangs out in coffee shops and is not tech-savvy. Her laptop and phone are old, and she goes to her friend’s house if she needs to use Wi-Fi. Pocket money is a luxury, as she lives under the poverty line.

But Anida has yet another burden. She has a history of schizophrenia since she was 4 years old. The condition causes anxiety, hallucinations and sleep problems. She often hears whispers telling her to harm herself. When she hasn’t been sleeping well, these hallucinations become more vivid.

With support from the National Health Insurance (JKN) program, Anida is able to see a psychologist and a psychiatrist to treat her mental health condition. She takes antipsychotic medication and uses sleeping pills to help her sleep. But Anida wants to reduce her medicine consumption. She wants to live freely without medication, just like her friends.

These challenges have not stopped her from pursuing her education. When she passed the national selection exam for state universities, her teacher recommended that she apply for the Jakarta Top Student Card (KJMU), which provides financial support for underprivileged students with good academic records. Anida was accepted into the program.

Alongside having her tuition paid, Anida receives Rp 8 million every six months. She gives most of the stipend to her mother to support their family. Her mother works as a maid for Rp 1.5 million per month, and her father is no longer involved with the family. When she was a child, Anida saw him abuse her mother, strangling her and stomping on her, almost killing her.

Anida’s situation has not stopped her from helping others. She and her friends were part of a movement to support a community in South Jakarta fighting against forced evictions. Anida lived among friends who understood her condition.

Queer and Without Family Support

Ang, 26, as a self-made member of Gen Z, without any support from their family, runs counter to the generation’s stereotypes. As a member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community, Ang left home to escape the mental pressure from their mother, who prohibited them to wear shorts outside and pressured Ang to get married.

Belonging to the LGBTQ community is still frowned upon in many families in Indonesia. In many cases, young people who identify as part of this group are sent away from home or to conversion therapy. Ang feared something similar would befall them if their family found out about their relationship with their partner, Ken.

So Ang left their Semarang home to live the life they wanted. After a while, Ang and Ken moved to Kudus, Central Java. Ang began working as an assistant at a bakery during the day and as a shop assistant at a local store during the night.

In 2016, the couple established a business. They rented a shop and started selling squash drinks. The beverages were popular among local teenagers, but the couple soon had to change their strategy, as the property’s landlord also sold drinks and felt their business was taking away from his.

Ang and Ken then began selling pancakes, then iced chocolate, but found little success. One day, Ang remembered that they had always wanted to have a cat, but their mother had forbidden it. Ang decided to open a cat grooming business with only Rp 500,000 in capital.

Ang and Ken promoted their business on Facebook groups in Kudus. Their cat care services soon started getting a steady stream of customers. But COVID-19 hurt business. A number of customers failed to make payments.

Meanwhile, demand for face masks and hand sanitizer had increased significantly. Ang saw this as another business opportunity.

Ang and Ken spent the last of their savings, around Rp 2,000,000, to buy health products. When the rent for the shop was due, they closed their cat salon. Ang continued to accept occasional bookings for home grooming, but their focus changed to managing orders of face masks. They also created mask straps, bracelets, and necklaces with beads. Ken helped them deliver the orders.

Ang used the money to pay rent and support themself. Their grit shows that, despite a reputation to the contrary, members of Gen Z can be self-made, without privilege or support from their parents.

Meager Wages and Married Young

A potential way out of poverty and of avoiding gossip, early marriage has attracted some members of Gen Z. Muhamad Agung, 22, and Siti Halimah, 20, a young couple in Bandung, met when they were child workers at a garment factory. Agung was 16 years old when he decided to drop out of school and work to support his family, while Siti was 14 and had not finished junior high school when she started working for the same reasons as Agung. She admitted that she sometimes longed to go to school but her dreams of becoming a doctor were dashed whenever she considered her family’s financial situation.

At the factory, Agung and Siti were employed as contract workers. Their wages were based on the number of garments they could sew in a day. In nine hours of work, Agung had to achieve the target of sewing parts of 800 pairs of pants per day. Otherwise, he was made to work overtime without pay. Agung was not the only child worker at the factory. He could not tell the exact number, but he said there “were a lot [of workers my age]” and they received the same treatment as the adults working there.

Agung and Siti got married at Siti’s mother’s request after the couple had dated for a year. When Agung proposed, Siti’s mother gave her permission, though Siti was only 17 years old and Agung 19 at the time. Siti also thought it was the best move, believing marriage could save her financially. Meanwhile, Agung’s mother also wanted the two to get married before the young couple became “the talk of the neighborhood”.

Now, Agung works even harder to support his family. He is still at the textile factory. His wages are between Rp 100 (0.7 US cents) and Rp 280 per piece, depending on the brand and the difficulty of the stitching. Sometimes he receives Rp 1.5 million (US$101) a month, sometimes Rp 3.5 million. To earn that amount, he must sew parts of 500 to 1,500 pieces of clothing a day.

But for Agung, this is better than unemployment. Unlike some privileged members of Gen Z who feel they are better off unemployed than receiving a low salary, Agung feels he must keep working, despite the meager pay, to support his family.

‘Stealing’ Hotel Wi-Fi, Low Wages and of the Sandwich Generation

Hayu, 20, not her real name, is a member of Gen Z living in Yogyakarta who is willing to take nearly any honest job to support her family. She has been earning money since junior high. One of her first jobs was washing her neighbor’s clothes.

“I received Rp 200,000 per month. I’ll do any work as long as it’s halal. I’m not ashamed,” she said. She also used to work as a housekeeper at the Wisma MM Gajah Mada University for six months after she finished her vocational education with a major in hospitality.

Hayu lived at her grandmother’s house, 500 meters from Yogyakarta Monument in the city center. However, living in the city center was not very comfortable. Rows of towering new hotel buildings surrounded the remaining housing areas. The only good that came of the new establishments was that Hayu could enjoy free Wi-Fi from a nearby hotel. She used it to watch TikTok videos in her spare time.

Other than scrolling through social media, Hayu spends most of her time working. For a year, she has been working as a shop assistant at a popular fashion shop in Plaza Ambarrukmo, one of the biggest malls in Yogyakarta. She works 8 hours a day. Now, as a permanent worker, she earns around Rp 2 million per month, making her the economic backbone of her family. Of that amount, she gives her mother Rp 500,000 to support their monthly expenses and Rp 1 million for her motorbike installment. Her mother mortgaged Hayu’s motorbike to pay a debt.

Hayu’s life is made more challenging by her tumultuous relationship with her mother. She said she was tired of shouldering the burden of the family and dealing with her mother’s emotional instability. Hayu’s parents married young. Her mother was only 16 years old when she gave birth to Hayu. Hayu’s father now lives a few houses away from the family.

Hayu knows there are other families like hers. Structural factors such as poverty and a lack of education cause many people to marry at a young age. Unlike the privileged members of Gen Z who dream of a happy marriage, according to UMN Consulting, Hayu said, “I don’t want to be like my parents. That’s why I haven’t wanted to have a boyfriend. If he’s not a good man, he will only add problems to my life.”

From a Privileged Life in Jakarta to Plantation Work in the New Capital

Stanley, a 26-year-old Chinese-Indonesian, seemed to have nearly everything in Jakarta. He spent his teen years studying at an international school and driving a Honda Jazz that his father had given him.

Stanley lived in luxury, but it did not offer him the freedom and happiness he was looking for, he said. His parents were divorced. He argued a lot with his father to the point that his father sent him away from home, vowing not to give Stanley any more money. From then on, Stanley was determined to earn a livelihood on his own.

Stanley flew 2,000 kilometers from Jakarta to Sepaku, East Kalimantan. He cut off contact with his family and started his life from zero. From Sepaku, he decided to work as a truck assistant and a construction worker in Tarakan, North Kalimantan, where he met his wife.

Recently, Stanley has been working as an agricultural exterminator, repelling pests from eucalyptus and acacia trees on a 30-hectare plantation. The work is dangerous. He often suffers shortness of breath from the fog of insecticide spray and his body is often itchy. He has lost some hearing because of constant exposure to loud engines. There are also mines placed in parts of the plantation to kill hogs, presenting a danger to him and his team.

But at the moment, this is the best job for him to support his wife and child and pay for his rented house. Stanley also plans to build a motorbike workshop in his front yard, but he may not be able to realize his dream because his house is under threat of being demolished for the development of Nusantara, Indonesia’s new capital city.

Stanley felt he had no choice but to buy a plot of land. He had his eye on a 10- by 15-square-meter plot, which was being offered for Rp 25 million. The seller was willing to accept payment installments over a long period, but in that case the price would increase to Rp 45 million.

It was too expensive for Stanley, so he ultimately chose not to make the purchase. He later found out that the seller did not hold the official deed for the land. Stanley would have been unable to have a new deed made because the government has forbidden the issuance of new land deeds in the area for the period of the new capital’s development.

“If we pay in installments and the owner of the original deed wants to take over the land, what happens then?” Stanley asked.

This piece, written by Risty Nurraisa, contains summaries of one opinion article and six narrative stories published in Indonesian as part of the #UnderprivilegedGenZ series. The writers of the individual pieces were Mawa Kresna, Permata Adinda, Yuli Saputra, Narriswari & Zefan Nugraha, and Pinaringan Asih. The series was shortlisted for the 2023 Excellence in Bahasa Indonesia News Reporting award by the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA).