(This story is based on interviews with Yusman and his wife, Falariyani, as told to Project Multatuli.)

I’d never been to work at sea, but when I did go–at the age of 42–that’s when I became familiar with death.

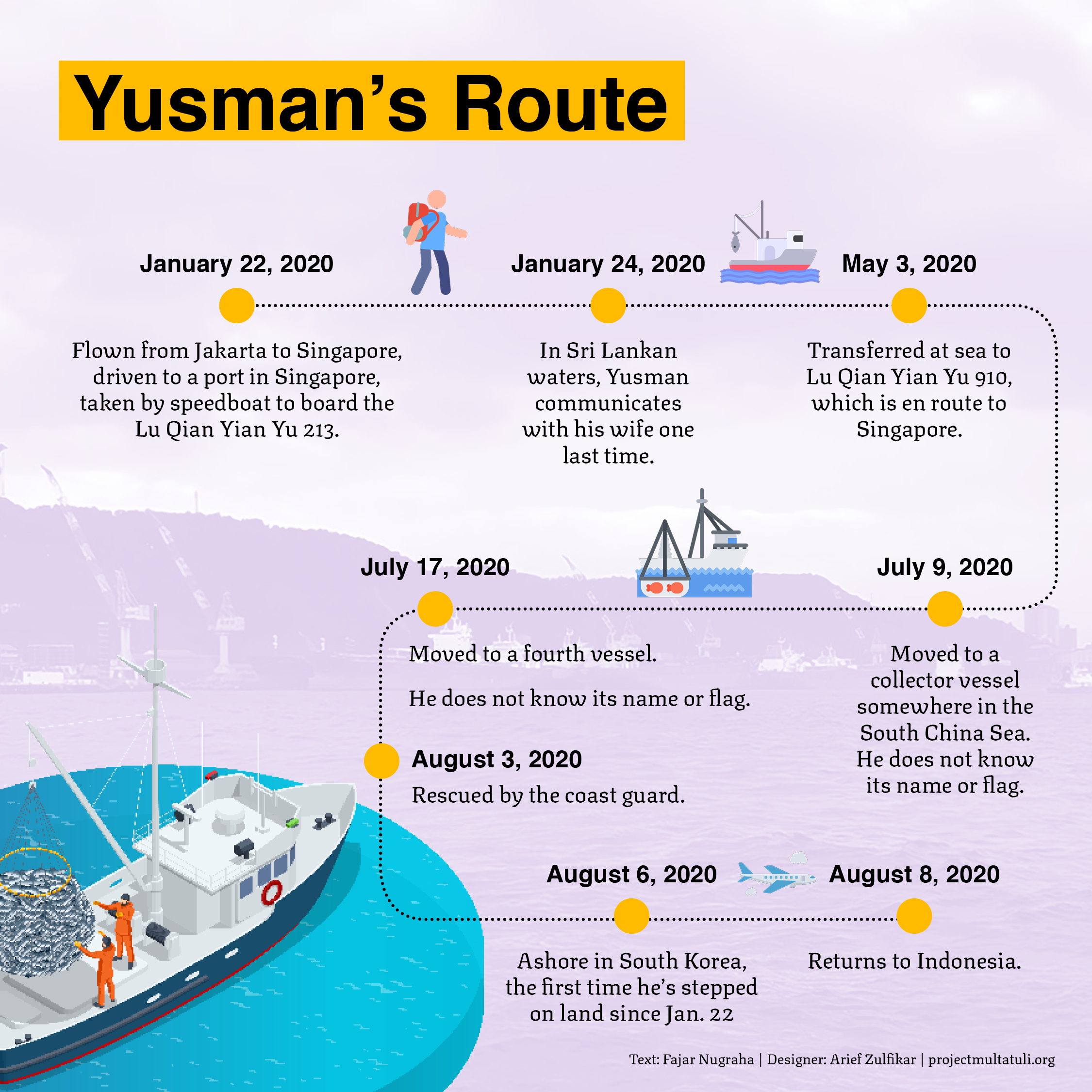

For six months and 15 days, I was a crew member aboard the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 213 and 910, Chinese-flagged fishing vessels, and was transported on two more vessels I’m not sure about. It was like digging your own grave out in the ocean, or that’s how the reporter who came to interview me described it.

On one particularly dark day in July 2020 onboard the fourth vessel, my friends and I ate raw flour in the room where we were confined. Another time, we snuck around to steal rice from the galley. Once in a while–if we managed to get two plates of rice, we would divide it equally among the eight of us, with only instant noodle flavor packets on top.

Two of my friends, Andri Juniansyah and Reynalfi Sianturi, chose to put themselves in God’s hands. They jumped ship from the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 910 when it transited the Singapore Strait. They couldn’t bear suffering on board any longer. Later, when reading the news, I was thankful: They were rescued by fishers from Riau Islands on June 6, 2020, after spending seven hours adrift.

We were held in a place meant to store fish that was only about a meter high on the fourth vessel, after I spent about six months on three different vessels. The captain kept us confined to avoid attention from coast guard patrols.

I slept in the fishold, with its stink. Every day, I tried to stay sane by thinking about my family, my house, my hometown. I didn’t know when I might go home–or whether I would live. Would I ever see my family again?

It Started with a Facebook Ad

After high school, I had a steady job for 14 years, working in sales for a distributor of aluminum and construction materials. The job eventually allowed me to continue my studies at STIE Jakarta International Polytechnic in Cempaka Putih. From there, I gathered the courage to start a family with my girlfriend, Falariyani. We married and were blessed with four children.

In 2015, I switched jobs and started as a training consultant for a human resource development company. I was bound by a three-year contract. I worked on one client, Astra Agro Lestari, until early 2019.

After that, things got rocky.

My family obligations increased, and so did my debts–not to mention so many other burdens and responsibilities. If they were rocks, my shoulders would’ve shattered from the weight of carrying them.

With what little nerve I had left, I borrowed money from the bank as seed capital, even though my work as a consultant did not bring in a steady income and was rather uncertain. My wife and I started selling all kinds of things, from mendoan (battered and fried tempeh), mie ayam (chicken noodles), to soto (Indonesian chicken soup). At one point, I went from market to market selling spoons. I had a stint as a driver for an online ride-hailing service. I did everything I could to make ends meet. Despite it all, our family expenses exceeded our income.

At the end of 2019, I began to consider working abroad, perhaps as a migrant worker. Making money was at the top of my mind. My wife and I decided to sell our car to fund my job search.

This was when my life became a whirlwind. I started looking online for jobs. On Facebook, I came across an ad offering jobs abroad. The ad connected me with a man named Abdul Aziz, who claimed that he was from East Java.

I contacted Aziz via WhatsApp. He was very convincing and seemed to realize he was talking to someone desperate who needed a good salary fast. I told him I needed a job quickly, that I didn’t want to waste time preparing documents and other requirements, or do anything that would require me to undergo training.

He told me he could help. I imagined I was going to work for a packaging or auto parts factory, or some other kind of factory. I didn’t really care as long as it paid enough to turn my family’s luck around.

Aziz gave me the number of another man named Syafruddin.

“He usually helps workers go abroad,” Aziz said.

The immigration office in Tanjung Priok

I reached out to Syafruddin immediately via WhatsApp. We chatted about the required documents. Syafruddin asked me to prepare my ID card, family card, high school diploma, a police clearance letter, birth certificate, and a photo of myself. All these documents were required for the application, he said.

Syafruddin said that I would work at a factory or a manufacturing company, just like I’d imagined. The job would come with a huge salary, he said.

It was a rosy picture that he painted. It hardened my resolve. I imagined working in South Korea, where the internet told me I could make as much as Rp21 million (US$1,464) a month. Syafruddin said yes to everything I’d asked for.

But then Syafruddin said I had to prepare Rp55 million–that’s how much money it would take to grease my application.

I was shocked. I tried to bargain. But he said that there was no room for negotiation. I would have to cough up the money.

Syafruddin and I met in person at the immigration office in Tanjung Priok, North Jakarta, on Oct. 10, 2019. There were many people there, applying for documents like the certificate granted to those who have completed basic worker safety training (BST certificate) or their Seaman’s Books, a kind of passport for sailors.

I remember the place in detail. There was a special lane where my picture was taken. I went through a short interview. The whole process took less than 30 minutes.

I didn’t understand what documents like the BST or Seaman’s Book were for, even after Syafruddin explained it all. At immigration, I met Andri Juniansyah and Dendi, other candidates represented by Syafruddin. Andri, who was from Sumbawa, would become my comrade, sharing the same fate.

It was only when Syafruddin helped me to get my BST certificate that I understood that it was a sort of license for ship crew members–and that I got it without any training.

He assured me that the BST I held in my hand was just temporary.

“The real BST,” he said, “has not yet been issued. This temporary BST is so that you can check off the requirements to make a passport.”

I started feeling uneasy. I was so sure I was going to work on land, not at sea. When I got my BST, I wondered for a moment: Was I not headed for a job on land?

After I asked Syafruddin directly, he said he was employed by a migrant worker employment agency called PT Asfiz Langgeng Abadi, with an address in Bekasi.

From the Rp55 million prep money I paid him, Syafruddin asked me to give him Rp10 million as down payment, right after applying for a passport in Tanjung Priok. I complied. Syafruddin gave me a receipt.

All the arrangements at the immigration office took about four hours. Three days later, Syafruddin said my passport was ready.

Waiting

While I was waiting, Syafruddin told me in December 2019 to sign up for a government program called “G to G” from the Indonesian Migrant Worker Protection Agency (BP2MI).

I was even more confused. While I had received an offer to work abroad from a different place, Syafruddin claimed that there was a limited government quota, but there were few openings because some people paid their application fees but later withdrew from the program. He added that I would have to pay an additional Rp10 million in “registration fees” to enter the G to G program if I accepted the other offer.

I knew of the BP2MI, but I had no idea about this so-called “G to G” program. (When I told this to the reporter writing this story, he said that the program referred to “Government to Government”, a BP2MI scheme for migrant worker placements in foreign countries. There is no charge for candidates; the only expense is IDR 300,000 in test fees.)

Since I didn’t want to pay the registration fee, I decided I would just wait for what Syafruddin had initially promised me.

Good news came, finally. In mid-January 2020, Syafruddin took me for a medical check up for my Seaman’s Book. I returned to Tanjung Priok.

We went for a check-up at a clinic known as Oilia Medical Center. It wasn’t just me. There was also Andri Juniansyah and three others. Syafruddin arranged for our departures.

Getting Underway

I had been selling goods at the Cileungsi Market in Bogor when Syafruddin told me I would be leaving the next day. He had already bought me tickets on Tigerair with a departure scheduled for 2 p.m.. The weird thing was that the flight was headed to Singapore’s Changi Airport, not South Korea, as I’d been expecting.

Once again, Syafruddin deflected my misgivings. He told me that I would transfer in Singapore for a flight to Korea. “Worse comes to worse and we don’t get a ticket, then you’ll get on a ship,” he said.

“You will arrive in Korea in two weeks at the most if you’re traveling by ship,” he added.

This caught me off guard. If I had to depart the next day, I needed to leave something for my wife and four children. At least a little bit of money to tide them over until I received my first paycheck.

I was confused, worried, anxious, panicky, and helpless. Everything was happening too fast. Everything had to be taken care of right at that moment.

My wife, Falariyani, and I, decided to pawn my motorcycle. We went to a leasing office in Tanjung Priok that gave us a loan of Rp4 million.

On the way home, my mind was filled with jumbled thoughts. I was on the verge of leaving my wife and four children to work in a foreign country.

I thought of reuniting with my kids when I came home. Would they pick me up? Would they rush to the door as soon as they saw me out front? Honestly, I had no idea what was going to happen.

On Jan. 22, 2020, I said goodbye.

The Journey

Syafruddin gave us a lot of instructions on our departure day:

Gather at Kalibata City, South Jakarta. Meet the others. We are expecting you to bring money to pay off the registration fee.

All the documents (passport, Seaman’s Book, BST, medical check-up results) wil be ready at the meeting point. Don’t bring too many clothes. There’s no need to bring a suitcase. This will make it easier to escape from the airport if there’s trouble.

The meeting point has been changed to Ellysta Jaya Hotel in North Jakarta.

I arrived at the hotel. Syafruddin didn’t waste any time before collecting the money, which he referred to as a “registration fee.” I paid Rp45 million via online bank transfer.

Afterwards, we headed to Soekarno-Hatta Airport in Tangerang, Banten.

Upon our arrival at Changi airport, someone was there to pick up me and the other workers and take us to a 7-Eleven. He gave me a list of names, and what I suspected was a letter of guarantee intended for another person.

That man directed us to an https://projectmultatuli.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/5668A357-39CA-4B12-902A-DAE1F707FCD7-1.jpegistrative counter that looked like a special lane. From there we ended up on a speedboat. At that moment, I was filled with confusion, panic, and stress. Where were they taking me? If we were destined for Korea, then why were we using this small boat?

As the boat moved further away from the shore, I saw Andri Juniansyah experience the same panic. The anxiety then turned into fear. In the middle of the sea–at which point I realized we were being escorted by the Singaporean coast guard–it turns out we were heading toward a Chinese-flagged ship.

The ship was named Lu Qing Yuan Yu 213, a fishing vessel for tuna and squid.

Day by Day

At first, the person who took charge of us treated us kindly. He took us to a room that was being made up when we arrived, showed us the equipment used to catch fish, and gave us crew uniforms and jackets. There were two other crew members from Indonesia already on board. Andri and I were berthed in the same room.

The first thing that crossed my mind on that first day aboard Lu Qing Yuan Yu 213 was that I was starving. Andri was, too. We hadn’t had anything to eat since the day before. My stomach was stinging with hunger.

We told the captain that we were hungry. On the galley table, there was plenty of delicious food. We thought the whole crew could eat it–but I only ate plain bread on my first day on the ship.

I met Agus, a crew member from Lamongan regency in East Java, who shared a stateroom with a Chinese crew member. Agus was a year younger than me; he had previous experience on a Taiwanese-flagged ship. He could speak Mandarin.

His roommate said the ship we were on was headed for the Indian Ocean, in the direction of Sri Lanka–not Korea. That was the moment my dreams of working at a factory in Korea were dashed. I felt faint.

Our days as crew members began.

The captain ordered me to keep working as long as the ship was moving. At first I was instructed to tidy up the tools and the nets. Then a foreman gave each crew member fishing gear.

With hydraulic-powered nets the size of half a football field, we started catching fish, learning on the job.

In those early days, we didn’t manage to catch many fish. Afterwards we started catching plenty of fish. Those were the hardest days. The workload increased. There was a point where we worked for 22 hours straight.

The last time I communicated with my wife was on Jan. 24, when I first had a meal aboard the ship, two days after leaving Jakarta. I didn’t have time to tell my wife who I was with.

By the time of Idul Fitri in May 2020, I was aboard the second ship, the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 910. Cellular service was hard to get. The captain confiscated our mobile phones soon thereafter. I kept thinking about my wife and kids. How could they eat? How do I tell my family and neighbors about my situation? How were my four kids celebrating Idul Fitri without their father?

Praying for the Dead

(Falariyani, Usman’s wife, picks up the story in Jakarta)

Yusman, my husband, whether he forgot or was just plain careless–I have no idea–didn’t ask how the company was going to arrange the receipt of his salary. I only realized that after he’d left. And where did he go? I had no idea.

It became so clear that we had been conned. We only realized this once I learned that Yusman was taken to a ship, not to work in Korea. We had expected that my husband would be able to transfer his salary from his bank account to mine–just like it works when people are on land.

I learned afterwards that in situations like this there’s a thing called a “delegated salary account”, which should have been me as his wife.

I did not receive a rupiah of his salary during the time Yusman disappeared. For almost half a year, there was no news. And I had to survive with my kids.

I started selling soto, fried tofu, mendoan, and other things, going from house to house. Sometimes I’d sell online. In the morning I would ride my motorcycle to the market and buy the ingredients I needed to cook. My youngest was only two years old. I tried hard not to cry. I’d go back home, start cooking, and do all that needed to be done.

All this was happening during the Covid-19 pandemic. I was hit hard. My oldest, who’s in middle school, started studying online, so he would deliver the orders if I was still cooking. This was how we spent our days.

There was a time when our relatives would give us Rp100,000, or Rp200,000. I kept on hoping that any day now, my husband would receive his salary and send it back home as quickly as possible.

Every day, I would stare at my phone, hoping for news. One month. Two months. Three months. There was no money wired, no news from Yusman. At that point I thought: Was my husband still alive? Could he have died?

I worried about his health. My husband gets sick easily, always catching colds. How could he survive at sea?

Every day at midnight, I felt like I was going mad. I would sit for hours staring at the clock. I would stare out the window, hoping Yusman would send me some kind of news. I imagined my husband suddenly appearing in front of our house. Every day, every hour, I would check my phone, just in case my husband called. Whenever a call came in, my heart would start pounding. “Maybe it’s him”, I’d think.

Don’t ask me about my health. I lost a lot of weight. I had trouble sleeping.

I kept thinking about how I would pay our mortgage and the monthly payments for the motorcycle that we had already pawned. A generous neighbor loaned me 10 grams of gold to help pay my household expenses.

When Ramadan came, I was in despair. Usually our fridge would be filled with food to break our fast or for suhur, even if it wasn’t that much. I was confused and miserable when the kids asked for food. I remembered Yusman, and was reminded of how we’d observed Ramadan together with the children.

My eldest asked, “Where is Father?” I couldn’t answer him, as I kept the pain in my heart to myself.

As there had been no news from Yusman for so long, his family in Sukabumi, West Java, even arranged a tahlil. The tahlil was conducted so that my husband would come home soon. To meet his family. To meet his kids.

Exploitation

(On May 3, 2020, Yusman and other crew members were moved to the second vessel, Lu Qing Yuan Yu 910. On July 9, 2020, he was moved to third ship, and on July 17, 2020, was moved to a fourth. Yusman did not notice the name or the flag flown by the third and fourth vessels). The transfer process is common for fishing vessels. It is called transshipment. Yusman continues the story.)

The other crew members and I asked several times to be returned home to Indonesia. While on the third ship, a collector vessel, we crossed into Chinese waters on July 16, 2020, and they wanted us to move to a fourth ship. We refused because it wasn’t in accordance with our letters of guarantee.

It was then that someone with the name Wili, claiming to be an agent for worker placement from PT Mandiri Tunggal Bahari, called us. He called to lure us to move to the fourth vessel. He said a crew member from his company had moved to the ship and received an additional salary of US$50 per month.

We also received a call from someone claiming to be from the Indonesian embassy in Beijing. He told us to continue working. We weren’t entirely convinced that he was really from the Indonesian embassy, especially because he asked to meet at the port in Beijing.

The Chinese crew members also intimidated us. They said we had until 11 p.m. to move to the other ship or the other workers were going to beat us up.

The next morning, I was handed a one-page statement. The statement, which was written in Indonesian and Mandarin, said that if we wanted to go home, we would agree to pay a fine of US$1,000 for the plane tickets and we would be deemed in violation of our employment contract. We were also forced to state that the statements were made “consciously and without coercion from any parties”.

Under pressure and eager to go back home, the other crew members and I ended up signing the statements.

Afterwards, we agreed to move to the fourth ship as we were promised that we would be allowed to get off at the port of Busan, South Korea.

It took the fourth ship about three days to get to Busan. During the journey, we weren’t forced to do any work. Once we reached Busan’s waters, the ship stopped for about four hours. Then it started back up again, headed for North Korea.

We got even more worried. We protested. The captain said they didn’t let us get off because “no ship was picking us up from the port of Busan.”

We were desperate enough to call the South Korean police, asking them to connect us with the Indonesian embassy. But it was a Sunday and the call didn’t go through. We resigned ourselves to our fate.

During those dark times–I thought I was going to die, I lost hope, and I was constantly panicking–we refused to work because we had been promised that we would go home. We also didn’t want to be separated on different ships.

On that ship, the eight Indonesian crew members were not given food. We were even forced to sleep out in the open on deck, where we only had thin mats and coats to sleep on. After that, we were moved to the one-meter fish storage space. That’s where we ate raw flour in order to stay alive.

On our 18th day, the ship headed back to China via Busan. The other crew members and I asked to make a phone call to Indonesia, but they did not allow it.

We were pushed out of the wheelhouse. The ship didn’t make it to China, it went back to North Korea via Busan, again without making a stop. We then called the South Korea police to ask for help, so that we could get off the ship and call the Indonesian embassy in Seoul.

That was when the ship we were on got chased by the coast guard.

At that time, one of my friends waved his hands to alert the coast guard, but the Chinese foreman caught him. We were then told to move to the storage room to hide us from the coast guard.

From inside the storage room, I heard the warning siren and a voice from a loudspeaker. Not long after, the ship stopped. The coast guard came aboard and looked around. The other crew members and I were told to get out of the storage room.

We were interrogated and then connected with the Indonesian embassy. Our ship was then escorted by the coast guard and the police boat from Ulsan Port.

At Ulsan, we got off. Each of us went through a health check-up and were quarantined at the port. When night fell, staff from the Indonesian embassy came to take our statements.

I always remember that day. The day I finally stepped back on land: Aug. 6, 2020.

Homecoming

I couldn’t contain my happiness on Saturday, Aug. 8, 2020, when I arrived at Soekarno-Hatta Airport. I prostrated myself in gratitude.

After our arrival, the other crew members and I were taken to the Jakarta Police headquarters to give our statements. I met my wife and kids there. I erupted in happiness.

The others and I were then taken to stay at the Marrakesh Inn Hotel in Tanah Abang for three days. My wife and kids slept over on the first night. On the second night, the crew members and myself underwent questioning by the police in the hotel room.

We were then taken to the Bambu Apus Migrant Worker Trauma Center, run by the Social Affairs Ministry. I thought it was only for a few days, but we ended up staying for a month. I underwent therapy to help me heal, as well as guidance to help me fight for justice after what I had gone through. Then they allowed me to go home.

You can imagine how I felt to be able to return home, to meet my wife and children, after leaving them without any sort of communication for 6 months and 15 days.

Epilogue

I have many regrets. I lost Rp55 million, which could have been used as seed money for some kind of business by my wife and me.

I’ve told you everything. It is up to you whether you think it was my fault or just bad luck.

The reporter who came to see me said my case was an anomaly. He said it’s not very often that there are ship crew members with a college education like myself, who find themselves lured to the high seas with sweet promises from a human trafficking and slavery network.

He said most of the victims were younger people who wanted to help their families out-eager to fix their parents’ homes or something like that.

He also said that my story added to the list of cases of modern slavery at sea. Every year, there are new reports of crew members dying onboard shady fishing boats, whether due to illness, violence, malnutrition, or exhaustion. Maybe I’m one of the lucky ones.

I only received Rp5.6 million. My wife and I are suing Syafruddin for the money we gave him, as the agent who conned me.

Syafruddin is now serving time in prison for human trafficking. He was imprisoned along with Karyanto and Muhammad Hasbar Yasir, also known as Daeng. They were employees of PT Duta Putra Group, the employment agency that issued a letter on Jan. 24, 2020, naming me and six others as their crew members.

That was the day I left for Singapore.

I’m still in touch with the other ship crew members, Andri Juniansyah and Reynalfi Sianturi. We have a WhatsApp group. We went through the same misery, the same suffering onboard that ship, and that has forged a strong bond of friendship between us.

Now, I’m working as a driver for a tower technician. I earn Rp100,000 per day. We are still working to the bone. The kids have to eat. The kids have to go to school. There’s the mortgage, and a million other obligations. Everything requires money. My wife and I are back to square one. The only difference is that now I have this story, which I have given permission to be written by the reporter who came to see me.

I also told him, the reporter: We are nobodies. We are just looking for justice.*

Interviews and text with Yusman and Falariyani were edited for clarity.

The English version of this story was made possible by the generosity of a Project Multatuli member, Sheany (translation), Karina M. Tehusijarana, a volunteer and also one of our members (English editing), and Christian Razukas, a volunteer (English copyediting).