Ribut Suratno had reached a boiling point. His left hand gripped the nape of the man’s neck, his right hand raised a machete. One slash was enough to decapitate the man, he thought.

On that day, Ribut was walking into a forest which was part of a coal mine area operated by the state miner PT Bukit Asam (PTBA) in Muara Enim Regency, South Sumatra. An employee of the company stopped him, refusing to let him through. Ribut was enraged and drew a machete. The situation then spun out of control.

Behind Ribut’s anger over something, which seemed to be a trivial matter, was not only his hurt ego but a complex web of problems that had become more complicated and bigger along with the growth of the mining operations in Muara Enim.

Born in 1970, Ribut used to play in the forest when he was a boy. For years, he has made a living from the woodland, which the locals call Banko forest. He now cultivates a farm of various crops covering an area of approximately 1-2 hectares there.

“Before there were mines, the forest was our livelihood,” Ribut said. “In the past, it was the community’s path. After the big company improved the path, it was called the company’s road. We no longer own it.” Ribut was referring to the “company’s road” he was walking on when an employee of the company stopped him.

Even though more than half of Muara Enim’s economy is supported by the coal mining sector, Ribut has never seriously considered the option of working in the “black gold” industry. His last period of formal education was vocational school, which he didn’t even graduate from because he didn’t have enough money.

“Even if I want to work there, it would be difficult for me to get a job there without some (company insider) who vouches for me,” he said.

For Ribut, coal mining actually does more harm than good. The Tegal Rejo he knew as a child was a beautiful village: Rubber trees were everywhere; but now they are no more. The Kiahan River, a tributary of the Enim River that separates the village from the PTBA mining area, used to be clear and full of fish and was a place to bathe; now it is cloudy and full of chlorine. These days, residents are forced to live with coal dust and dirty houses. Their nostrils fill up with black soot.

There were times when the walls of homes in Tegal Rejo cracked due to blasting carried out by PTBA to uncover and extract coal in an area located only a few kilometers from the villages. The company usually gave rice and milk to the house owners as a form of compensation. “After (the house owners) stopped complaining, they also stopped giving out the rice and milk,” Ribut said.

And to top it off, Ikhwan Naza, Ribut’s eldest son, only eight years old, died in 2013 after drowning in an abandoned mine full of tailings PTBA once operated. His friend, Ferdi, suffered the same fate.

Around a year or two after Naza’s death, Ribut crossed the Banko forest. A PTBA employee confronted him. Ribut’s left hand gripped the nape of the employee’s neck, while his right hand raised a machete.

“Your head is hard,” he whispered. “I want to cut it off.”

Not far away, a gigantic black hole lay gaping open. Excavators were scraping the earth. Trucks were passing by, carrying coal. Busy. Noisy. However, Ribut could no longer hear anything.

***

Yedi Nopmalison would do anything to work for a coal company. That was his goal after graduating from high school in 1994. His logic was simple: as a native of Muara Enim, the land of coal, he should be able to make a living from the black rock.

For Yedi, it would be ridiculous if he weren’t able to benefit from the wealth of his hometown. “Why are we like dead chickens in a rice barn when we have ‘gold’ here?” he said.

As he only had a high school diploma, Yedi’s choices were limited. He could only be a coal truck driver or operator of heavy equipment such as excavators or bulldozers. He dared not dream higher than that. The problem was, he didn’t know how to drive and didn’t have a driver’s license. Companies were also reluctant to recruit people without work experience.

But Yedi refused to give up. It took years but he finally obtained a truck driver license and got a job in 2000 as a coal truck driver at a company that supported mining activities.

“I’ve always been a driver. A dump truck driver,” Yedi said, proudly.

Yedi hopes he does not have to change jobs again. A coal truck driver’s income is around Rp 7 million or about US$490 per month. The basic salary is Rp 3.4 million, and the remaining is overtime pay.

However, many residents of Muara Enim have no choice. Many do not have the education and skills required to apply. At the end of the day, as Yedi said, they are like hungry chickens waiting to die in the rice barn. For them, there is no splash of prosperity derived from coal.

***

Coal has changed Keyjhon’s life. In the 1990s, he was the head of a gang of bajing loncat—a local term for truck robbers—operating in Lawang Kidul. Now, he is one of the bosses of artisanal coal mines managed by the residents of Muara Enim.

Keyjhon stopped his robber days in the early 2000s. He then got a taste of the timber business and became the head of security at two private coal companies: PT Bara Anugrah Sejahtera and PT Pacific Global Utama. It was the experience of working with the two companies that paved the way for Keyjhon’s understanding of coal mining’s intricacies.

In 2007, an opportunity arose for Keyjhon to directly apply his knowledge. He met Herman Effendi, a man also born and raised in Darmo, who asked Keyjhon to join him to develop artisanal mines in and around Darmo.

After hearing about the artisanal mines in Sawahlunto City, West Sumatra, Herman thought of opening a similar business in his own village. So he began inviting the locals to work together. One of them was Keyjhon.

Herman brought 23 miners from Sawahlunto to pioneer the work of the first artisanal mine in Darmo in 2007. It was located on the bank of a small river called Jamile Bangke. The coal seam was so visible that workers did not have to dig deep.

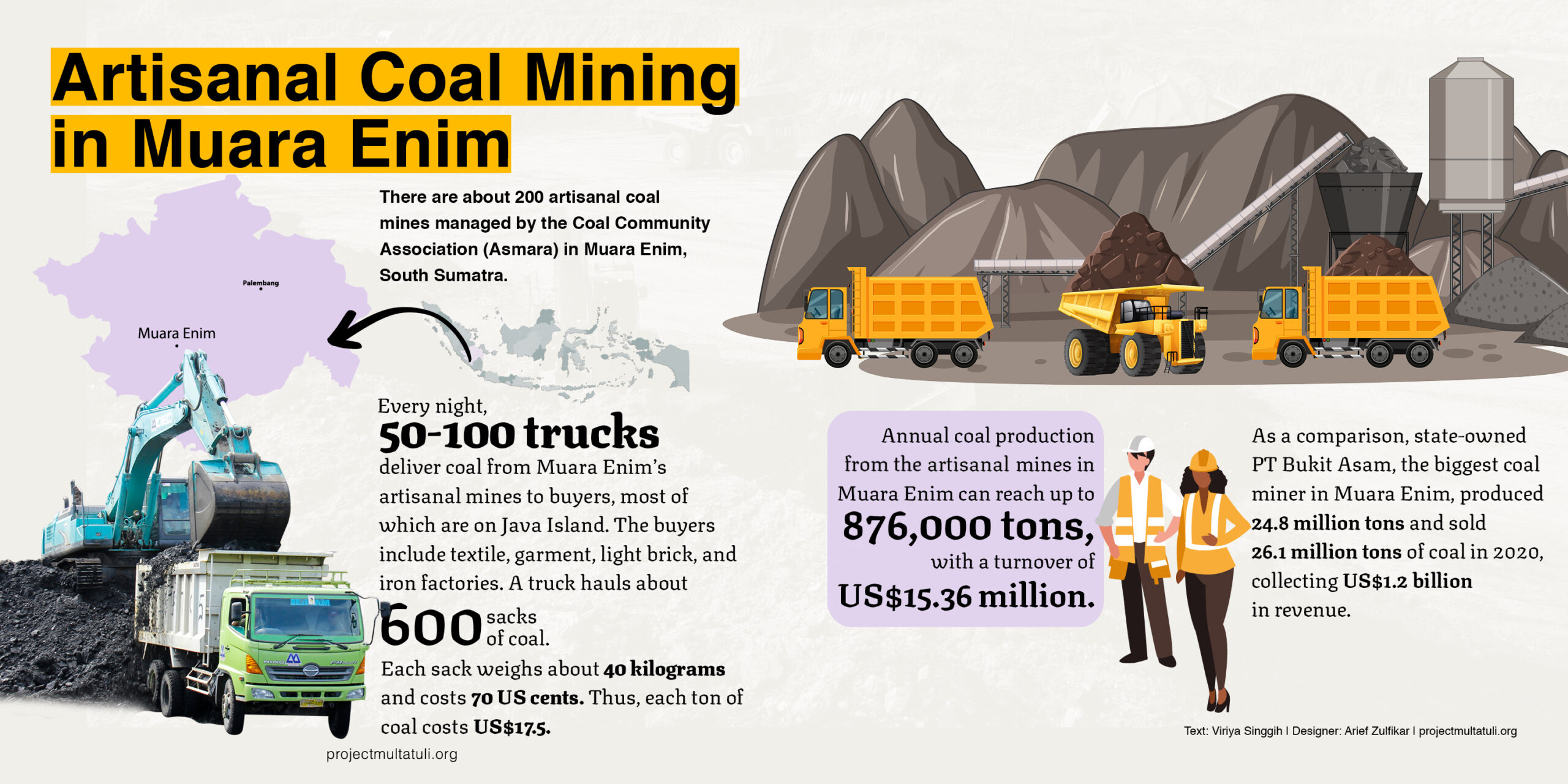

Herman continued to persuade the locals to join his venture. More and more people learned how to operate coal mining on their own and the artisanal mines have now reached around 200 spread over two subdistricts in Muara Enim: Lawang Kidul and Tanjung Agung.

“(We) help the government create jobs in our own villages,” said Herman.

Currently, it is estimated that around 7,000 people are involved in artisanal mining operations in Muara Enim. About 2,000 of them are not locals; they come from Lampung, Pandeglang, Bandung, Bali, and even Timor-Leste.

Everyone lines up to get their slice of the “coal cake”. Some become miners or diggers, motorcycle taxi drivers who carry the coal to the stockpile, laborers who transport coal to trucks, or other occupations.

The local miners earn Rp 2,000 (14 US cents) per sack and often Rp 140,000 (US$9.80) per day. Land owners get some share too: Rp 1,000 per sack. Meanwhile, the wages of motorcycle taxi drivers range from Rp 1,000 to Rp 3,500 per sack of coal. On average, they can earn Rp 300,000 to Rp 500,000 a day.

The daily income of a motorcycle taxi driver is greater than that of a miner, but they also have to use their own motorcycle, modify it to haul heavy sacks of coal, and spend money on any needed repairs and maintenance. Coal hauling is not kind to personal motorcycles.

Artisanal mining thrives in Indonesia because of the high demand for cheap coal to fuel various industries, especially on Java Island. At first Herman had to find buyers. He visited several factories one by one and brought along samples of Darmo coal to help his cause. The first buyer was a textile factory in Serang, the capital city of Banten.

As time has gone by, Herman and his business partners have attracted more and more buyers. Herman said many factories require coal with medium calorific values, and this type dominates coal production at the artisanal mines led by Keyjhon in Muara Enim.

Every night, 50-100 trucks carry coal from the artisanal mines and transport them to the buyers, mostly in Java. The buyers include textile, garment, brick, and iron factories. On average, each ton of coal is purchased for Rp 250,000, or US$17.50.

In comparison, Indonesia’s coal reference price throughout 2021 continued to increase to US$161.63 per ton in October, after starting at only US$75.84 in January. The price is determined once a month by the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry and is used as a benchmark for direct coal sales on a free-on-board basis (meaning the buyer is at risk once the seller has completed shipment of the coal).

With the calculation above, the daily turnover of artisanal mining in Muara Enim could reach Rp 600 million or US$42,000 a day. This revenue has continued to increase from one year to the next as an increasing number of people depend on “illegal” coal for their household income.

“Although we live within the PTBA area, even if we have law or economics degrees, whatever degrees, we can’t necessarily join and work at PTBA. So, PTBA is of no use to us actually,” Keyjhon said. “Instead of just being spectators, it’s better if we fight (for our share).”

***

Tegal Rejo was quiet that afternoon on Feb. 2, 2013. Tukiki was relaxing in front of the house while watching her nephew, Ikhwan Naza, run around in the yard.

Everything went as usual. Tukiki, born in 1951, had retired and enjoyed his life at home, while his youngest brother, Ribut Suratno, was working at a brick depot a few kilometers away.

Tired of playing, Naza sat down and munched on some snacks. Not long after that the 8-year-old boy stood up again. He saw a loose kite and he and his friend ran after it. Tukiki let the boy go not thinking anything bad would happen.

While the sun was setting, his neighbor rushed into Tukiki’s house, shouting repeatedly, calling out the name of his brother. “Pak Ribut! Pak Ribut!”

“What’s wrong?” said Tukiki. “Pak Ribut isn’t home.”

“Uncle, Naza fell into the mudhole!”

Tukiki rushed to the company’s abandoned mine. When he arrived there, Naza was lying on the edge of a tailings pond. His body was full of mud; he didn’t move. Tukiki’s heart sank.

He and his neighbors tried to revive Naza themselves. Later, they took him to a hospital run by PTBA. But it was too late.

Ribut came home at night. Naza was no longer there.

***

Many illegal miners in Muara Enim thought that while the big coal companies grew larger and larger, the local people only received mere crumbs compared to what the companies got. That was why they began joining forces to mine coal on their own, taking what they believed to be rightfully theirs, at the risk of being constantly hounded by the police.

“PTBA is too greedy. Its mining area is already big enough,” said Keyjhon.

When PTBA first became a limited liability company in 1981, its exploitation area was 7,700 hectares. By the end of 2020, its coal mining permits for operation and production had covered 93,528 hectares (twice the size of the province’s capital, Palembang), including around 66,000 hectares in two districts in South Sumatra: Muara Enim and Lahat.

In 1981, PTBA’s coal output was merely around 50,000 tons. In 2020, its production stood at 24.8 million tons. That is nothing compared to the company’s total coal reserves and resources, which reach 3.2 billion tons and 8.6 billion tons, respectively.

The entire coal reserves on Sumatra stand at 12.96 billion tons, while the resources total 55.08 billion tons. Even the figures are still below those of Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo), whose reserves and resources reach 25.84 billion tons and 88.31 billion tons respectively, according to official data.

Hence, Keyjhon believes that what they take from their own land is actually not that much in comparison. Keyjhon now leads the so-called Muara Enim Coal Community Association (Asmara), which manages artisanal mines within the mining permit areas of five different companies: PTBA, PT Bara Anugrah Sejahtera, PT Manambang Muara Enim, PT Pacific Global Utama, and PT Sriwijaya Bara Priharum. But Keyjhon claimed that the lands on which locals mine the coal never belonged to the companies. He said out of the five companies, only PTBA made a fuss over the artisanal mining activities anyway.

PTBA has reported Asmara miners to the police 20 times in the last 15 years, according to the association records. Keyjhon said the police had recently been more careful not to act rashly against artisanal miners because doing so risked social unrest.

At the time of this reporting, the last time the police visited Asmara’s artisanal mines was in September 2021, said Herman Effendi, Keyjhon’s business partner. First the South Sumatra Police from the provincial precinct arrived. They did not make any arrest but asked Herman to check on the illegal mining activities. Herman said he took the police to the artisanal mines and told them the land did not belong to any of the companies. The South Sumatra Police, Herman said, excused themselves and left without making any arrests.

But two days later, six people from the National Police headquarters in Jakarta showed up. They stopped by three claims where artisanal mining was taking place and arrested 11 miners and motorcycle taxi drivers who happened to be there.

Even so, Herman said the arrests did not interfere with the activities of artisanal mining in Asmara. The operations proceeded.

The special crime investigation unit of the South Sumatra Police confirmed the arrest of the 11 illegal miners and motorcycle taxi drivers, but declined to comment further. Meanwhile, the National Police headquarters in Jakarta did not answer any questions regarding artisanal mining in Muara Enim.

Herman questions the attitude of the company, the police, and the central government towards artisanal mining in Muara Enim. For him, it is simple: Artisanal mining is illegal, but it gives thousands of people a livelihood that can last decades. Hence, he said the government should legalize artisanal mining.

The 2009 Mining Law permitted artisanal mineral and coal mining activities under several conditions. For instance, artisanal mining activities took place at a location for at least 15 years before it could be authorized. The authority to determine an artisanal mining area rested with the local regent or mayor.

Furthermore, after an area was designated an artisanal mining area, individuals, community groups, or cooperatives had to apply for a five-year community mining permit. The permit holders were required to follow regulations related to occupational safety and health as well as manage the environment with the local government.

Referring to the law, Herman tried to propose that four artisanal mining claims in Muara Enim in 2009 be considered legal, community mining areas. However, his attempts never bore fruit, probably because those mines were relatively new while the minimum requirement was 15 years. He repeatedly negotiated this matter with the regional https://projectmultatuli.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/5668A357-39CA-4B12-902A-DAE1F707FCD7-1.jpegistration and the legislative council of Muara Enim to no avail.

Then, the 2020 Mining Law was issued, altering some provisions in the previous law. Artisanal mines are now only allowed for minerals and rocks such as river pebbles and sand. No place for community coal mines. The authority to determine the community mining area and issue the permit is controlled by the central government, not any regional head.

There are options to legalize artisanal mining, though. Illegal mineral miners are allowed to form a partnership with companies holding permits, apply for a permit to provide mining services, or propose their mines be considered legal community mining areas. Illegal coal miners, however, cannot strike a partnership with companies or render their mining claims legal. They can only provide mining services or apply for a mining permit as a cooperative or region-owned enterprise.

Even so, Asmara still insists on pursuing a partnership. Moreover, the current regent of Muara Enim, Nasrun Umar, tends to support Asmara’s efforts to legalize its artisanal mines.

Nasrun has been in office since February 2021 after his three predecessors were arrested, consecutively, for their involvement in graft cases. They are Juarsah and Ahmad Yani, who were arrested by the Corruption Eradication Commission for the bribery case of 16 road construction projects, and Muzakir Sai Sohar, who was arrested by the South Sumatra High Court in a bribery case about forest land conversion.

After inspecting the artisanal mines on June 9, Nasrun said there were two options for illegal miners: create a cooperative or a village-owned enterprise. “Because this concerns the sustainability of people’s lives, we must provide solutions on how mining carried out by the community continues but in a legal way,” he said.

This cooperative is expected to partner with companies holding mining permits. That way, it can only sell the coal production of its members to partnering companies. The cooperative must pay income tax to the state and collect value added tax from its coal sales.

Companies do not have to worry about compensating people’s land as they could just let them mine and buy their output. However, the company also has to bear all costs to carry out reclamation and post-mining activities at the abandoned artisanal mines.

“It shouldn’t reduce the company’s production if it wants to absorb coal from the artisanal mines,” said Yandri, another big player in Muara Enim’s artisanal mining operations. “Who will be harmed? Nobody. The company doesn’t even need to acquire land anymore.”

The leaders of the artisanal mines later decided to form a cooperative in their pursuit of legality. The legal process to form Lawang Kidul-Tanjung Agung Coal Prosperity Cooperative was completed in August 2021. However, PTBA, the largest coal miner in Muara Enim, firmly rejects that idea. Venpri Sagara, general manager of PTBA for the Tanjung Enim operations, said artisanal mining clearly violates the law.

“We are a state-owned enterprise. An SOE must be an example for other mining companies. So, it’s not that simple,” Venpri said. “They don’t have a mining business permit, they don’t have the competence, and I regret to say that they don’t understand the risks.”

Asmara’s mining operations in Lawang Kidul and Tanjung Agung are indeed high-risk activities. In the past, the illegal miners used to manually clear the land. Five or six people worked together to dig a site to a depth of at least 4-5 meters for a full month before starting to mine coal with pickaxes.

Now, heavy equipment is used to clear land, although the miners continue to dredge coal traditionally, without helmets, masks, or other safety equipment. They work like day laborers building houses or repairing gardens in a residential complex. In addition, the illegal miners used to work underground. They would dig tunnels as far as 200-300 meters, without support posts, and dredge the coal there.

Accidents are not uncommon. The most recent was in October 2020, when a landslide occurred, killing 11 workers. Tunnels can also explode at any time due to the high levels of pent-up methane gas. Therefore, according to Keyjhon, the Asmara miners have recently abandoned the underground method, though some shafts are still visible at certain claims.

Meanwhile, PTBA acknowledges it has not legally acquired all of the residents’ land within its permitted mining areas. The permit gives PTBA the right to manage the coal deposits, not to control the land, and the company acquires the land in stages as needed. However, the company feels that residents still have no right to mine coal in those areas without a permit even if they have title to it.

The central government apparently agrees with PTBA. Ridwan Djamaluddin, the director general of mineral and coal at the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry, has firmly argued that illegal mining violates the law and must be eradicated, especially considering the environmental damages and safety risks.

He said the illegal mines violated Article 33 in the 1945 Constitution, which states that natural resources should be exploited for the welfare of the people. Ridwan claims only a small group of people, including big and greedy local investors, controlled and benefited from illegal mining. As a result, the state loses a large amount of income; its value is approximately equivalent to the current state revenue from the mining sector.

“We have to take action against illegal mining operations just like we fight against drugs, we fight against corruption,” Ridwan said. “What is difficult is that the number of such mining operations, or the number of perpetrators, is far more than the number of officers. However, what is even more difficult is the involvement of the parties who are supposed to curb (such activities).”

As of September 2021, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry recorded that there were at least 2,741 illegal mining locations throughout Indonesia; 2,645 of which were hard-rock, mineral mines, while the rest were coal operations. Specifically for South Sumatra, the government noted there were only 33 illegal coal mines within PTBA’s mining permit areas, even though Asmara said the number of mines they managed in Muara Enim alone had reached around 200.

The ministry has established a task force to deal with this matter. It is expected to curb illegal mining activities or help formalize them through several available options.

However, the illegal miners in Muara Enim say if they don’t take matters in their own hands, they will never get their fair share of prosperity naturally originating from their homeland. For them, they are the actual victims who have been wronged by the state, which has violated Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution.

***

God seemed to smile upon Hapriansyah. On the afternoon of January 22, 2020, bulldozers were moving back and forth in the neighborhood unit 6 of Tegal Rejo Village, Muara Enim, leveling ground under a cloudy sky. The area would soon be ready for the construction of a subsidized housing complex, which Hapriansyah believed would help him make a fortune.

Hapriansyah, or “Apri” for short, could not resist the urge to share his joy. He recorded and then broadcast live the leveling work on his Facebook account, while occasionally chatting and joking with several bulldozer operators.

“This is the progress of the construction of 100 houses over an area of 1.5 hectares,” Apri, who owns a heavy equipment rental business, told his friends on Facebook. “We’re excited to work today.”

Apri had spent a lot of money, time, and energy to ensure the smooth construction of the housing complex. He had teamed up with a developer that would build the houses. Apri’s tasks were leveling the ground, building roads, and installing power poles. In total, he installed 22 electricity poles, each at a cost of Rp 4.5 million (US$315).

The plan was that the buyer would pay a down payment of Rp 2 million (US$140) and monthly installments of Rp 500,000 over 12 years to own a house in that complex. Apri thought many people would be interested. And he was right.

However, on that afternoon Apri did not know that within only two months, his luck would go up in smoke. Neighborhood unit 6 of Tegal Rejo was located right next to the PTBA coal mine, and the company dumped tailings all around it. One day, heavy rain poured down, causing the spoil to enter the neighborhood unit area. Suddenly black mud was everywhere. Land and farms were damaged and many power poles collapsed. Those that were still standing tilted because the ground was uneven.

Apri suffered a huge loss, estimated to reach Rp 1 billion (US$70,000). That figure does not include the loss born by the people who had bought the land to begin with. He believes PTBA should be responsible and compensate him and the buyers. Last year, he said, representatives from PTBA met with residents of Tegal Rejo who were affected by the company’s mining operations. They promised to compensate the residents. But after that, they disappeared.

“I am trying to fight for my rights. I used my farmland to build the housing complex. I installed facilities. Everything is now ruined,” said Apri, a native of Tegal Rejo. “Our land, our farms, everything has been damaged; please compensate for it fairly.”

The disaster on Apri’s land was not the only time Tegal Rejo in particular, and Muara Enim in general, experienced disasters. Many Tegal Rejo residents believed that mining operations had impacted their environment and health.

There are 22 companies with coal mining permits (IUP) and one with a coal contract of work (PKP2B) operating in Muara Enim today with a total mining area of 145,213 hectares, based on the 2020 government data processed by NGO Action for Ecology and People’s Emancipation (AEER).

One of the impacts of coal mining is the significant decline in the water quality of the Enim River in Lawang Kidul, according to a 2016 research paper by F.Z. Diplomas and colleagues from the Indonesian University of Education (UPI).

The culprit is the wastewater from the coal-washing activities carried out by companies operating around the river. Even after the wastewater is processed in a slurry pond, some of the acid waste still leaks into the sub-watershed of the Enim River and its tributaries, including the Kiahan River that borders Tegal Rejo with PTBA mining area.

As a result, the river water becomes cloudy, the oxygen level decreases, causing fish to die, and the water gets harder, which can trigger diarrhea when consumed by humans.

Nevertheless, Venpri Sagara from PTBA disagreed that his company was said responsible for polluting the river. “The wastewater flows to the slurry pond first,” he said. “Out of the pond, the water is clear, in accordance with the environmental quality standards.”

Floods are another problem. In early May 2020, for example, 30 houses were submerged in massive flooding in the neighborhood unit 14 of Tegal Rejo. At that time, PTBA’s excavated soil was eroded by heavy rains, causing it to slide and enter the Kiahan River. The river water overflowed and then hit the residential area.

“We admit that the erosion was our fault. But was the flood, which submerged the residents’ houses, 100% our fault? I don’t think so. Because if you want to know, houses that were first affected were (only) five meters away (from the river),” Venpri said. “We have bought the land (where those houses were built).”

In 2020, 38 villages and sub-districts experienced flooding in Muara Enim, down from 44 in the previous year, according to Statistics Indonesia. Meanwhile, landslides occurred in 22 villages and sub-districts in 2020, up from 20 in the year before.

Apart from negligence in mining practices, floods and landslides can also be triggered by the lack of water catchment areas due to deforestation. Land clearing and the development of coal mining infrastructure have wiped out forest areas in Muara Enim. In the 2019-2020 period, South Sumatra lost 37,170 hectares of forest cover, and Muara Enim contributed 2,038 hectares to the loss, according to NGO Hutan Kita Institute (HaKI).

Forests aren’t the only land cover affected: agricultural land has also been converted into coal mining areas. Many people have given up their plantations and rice fields and have transitioned them into mining areas. Statistics Indonesia recorded that from 2008 to 2017, the area of rice fields in Muara Enim shrank by 36% to 23,407 hectares, while plantations area dwindled by nearly 30% to 237,164 hectares.

As a result, more people in Muara Enim dream of working in the mines instead of the rice fields or plantations. Examples include Yedi Nopmalison, who was ready to do anything to become a coal truck driver. They duke it out, fighting over slices of the “coal pie” that is both so alluring yet threatening at the same time.

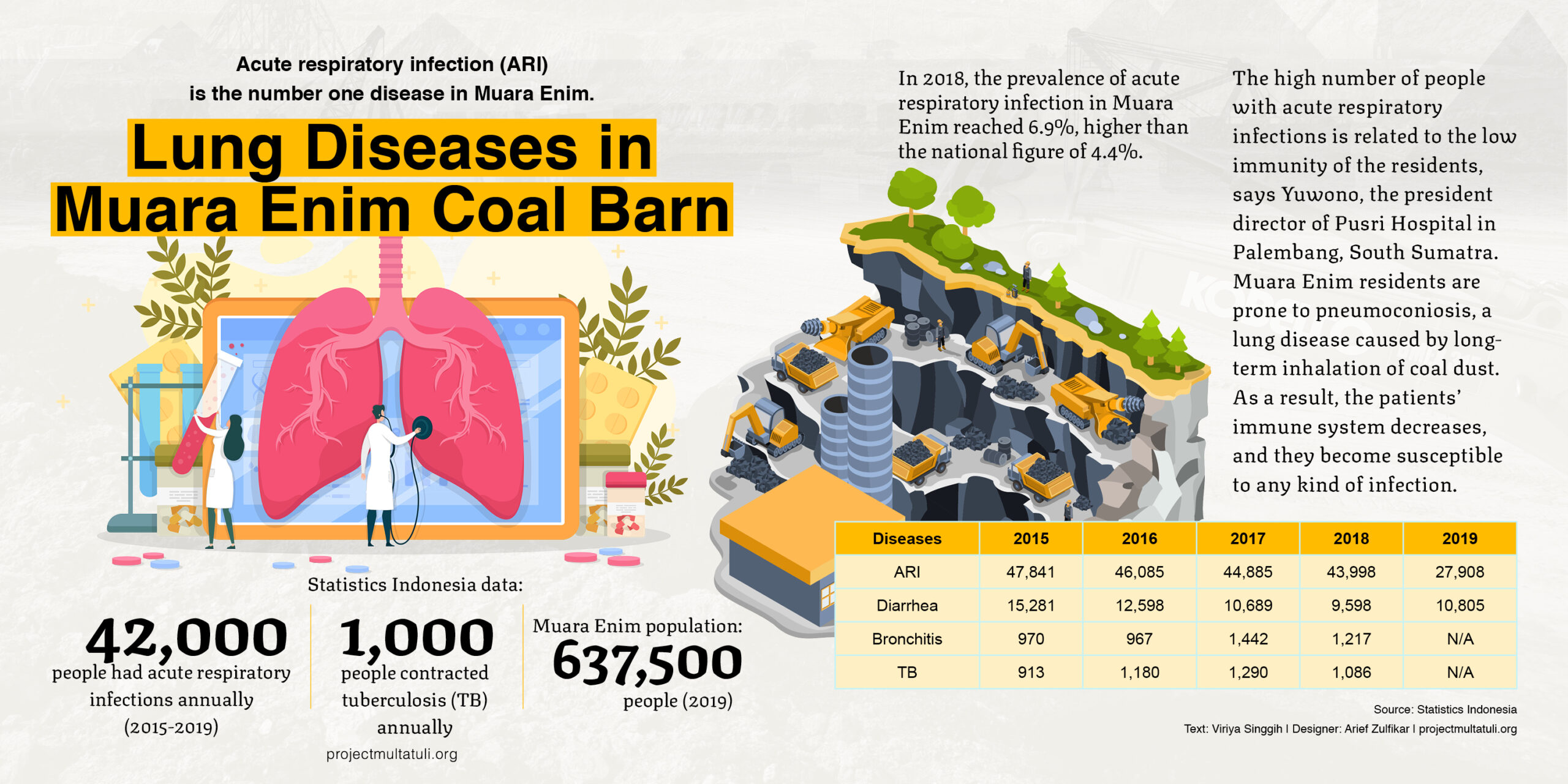

After working for more than two decades in the coal industry, Yedi understands that he and his colleagues on the ground are in a vulnerable position. Heavy equipment operators, for example, often suffer from hearing loss after retiring because they have been exposed to loud noises for too long. Meanwhile, coal truck drivers like Yedi can easily contract tuberculosis (TB) or acute respiratory infections (ARI) if they neglect to wear masks.

“If we don’t anticipate it by ourselves, TB is inevitable for those working in the mining sector,” Yedi said. “For me, thank God, so far I haven’t caught TB. Thank God. I hope not.”

ARI is the number one disease threat in Muara Enim. Statistics Indonesia data show that the number of people contracting such an infection averaged more than 42,000 a year in the 2015-2019 period. Moreover, around 1,000 people contracted TB annually. As a comparison, the total population of Muara Enim was 637,500 at the end of 2019.

The high number of people with ARI is related to the low immunity of the residents. Yuwono, the president director of Pusri Hospital in Palembang, said that Muara Enim residents are prone to pneumoconiosis, a lung disease caused by long-term inhalation of coal dust. As a result, the patients’ immune systems are diminished, and they become susceptible to all kinds of infection.

“Don’t get me wrong. The coal or its dust doesn’t cause acute respiratory infection. It causes vulnerability,” Yuwono added. “So, the residents are already susceptible to various diseases, because the dust issue is very likely to reduce their quality of health.”

Responding to this matter, Venpri of PTBA said that ARI can occur due to various factors. The trigger is not only coal dust, as it could also be road dust, according to him. He said the company routinely waters the roads to prevent coal dust from circulating. However, some residents, including Apri, question the effectiveness of these actions.

On the whole, the situation has gone awry. Muara Enim is a “dirty energy barn”, a regency with the largest reserves of “black gold” in South Sumatra, the location of operations and head office of state miner PTBA.

Here, rivers are polluted, floods and landslides occur routinely, forest areas and agricultural lands are shrinking. Here, land conflicts are common, illegal mining is everywhere, and the people are vulnerable because of the poor quality of health.

Here, we can see a snippet of dystopia.

***

Dystopia is possible if Muara Enim still carries on as it is today. Coal is now exploited everywhere. But what is going to happen when coal runs out or no longer turns a profit because clean energy has become the number one option?

In May 2021, President Joko Widodo, popularly known as “Jokowi,” instructed state electricity firm PLN to stop the construction of new coal-fired power plants, except those that already began construction or reached financial closure. Two months later, Indonesia submitted its updated climate commitments to the United Nations and set a deadline to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2060 or sooner.

Considering all that, PLN issued a new electricity procurement plan (RUPTL) for 2021-2030 in early October. During this period, PLN only aims to increase the capacity of Indonesia’s coal power stations by 13.8 gigawatts, down significantly compared to the planned addition of 27 GW in the previous RUPTL for the 2019-2028 period.

The 2021-2030 plan is expected to be the basis for Indonesia to achieve its zero-emission target. PLN will start retiring the nation’s coal power plants in stages starting in 2025 until there aren’t any such facilities by 2056.

Jokowi has a track record of being fickle and impulsive when determining national energy policies. But someday, Indonesia will be in a tight spot because the world has put a premium on clean energy; it will have to show that it is serious about leaving coal behind. What will happen to Muara Enim and other coal towns in the country?

Ilwan Utama, the head of Darmo Village, suggested that his residents switch to work in the livestock sector when coal mining is no longer permitted. When asked further about the matter, his response: “It’s still a long time away.”

It is different with Rimulati, a resident of Talang Jawa Hamlet in Tanjung Enim who has worked at some coal mining service providers since the 1990s. She is already jittery over the future fate of Tanjung Enim. “That’s what we’re afraid of. It’s going to be a ghost town.”

Anticipating such a possibility, PTBA as the largest miner in Muara Enim plans to transform Tanjung Enim into a tourist city. “We really have to lure in the money. Just like Bali,” said Venpri Sagara from PTBA.

The next question: What kind of attractions can bring people to Tanjung Enim?

Venpri was silent for a moment. He then said, “This Tanjung Enim… It’s difficult when it comes to tourism.” Like it or not, he said, something new must be created. There are some ideas that have been thought of, such as creating mining tourism and ecotourism.

No one has a concrete answer about Muara Enim’s future, about its land that is already full of holes, its polluted environment, or its residents whose lives have mostly been spent earning a living from coal.

But one thing is certain: When coal has turned into a worthless black rock, the value of the damages it has caused may never be replaced.

Not with money. Not with goods. Not with life.

***

Ribut Suratno’s child died after he drowned in a large hole full of mining waste. A week after the incident, PT Bukit Asam’s CSR team stopped by his house, apologized, and gave a compensation of Rp 5 million (US$351). Ribut did not say anything to them.

Ribut used some of the money to buy rice, which he distributed to orphanages. He then donated the remainder to some mosques and asked for a prayer for his late son, Ikhwan Naza.

That’s it. He could not do anything more than that. He felt powerless. Even if he wanted to sue, he thought he would certainly lose. He tried to accept PTBA’s apology.

Venpri Sagara from PTBA wondered why a small child could play so far from his home in neighborhood unit 14 of Tegal Rejo, cross the Kiahan River, and drown in the company’s tailings pond.

“I’m not saying that it’s the parents’ fault for not taking care of their boy. No,” Venpri said. “But it’s really far away, you know.”

Ribut had never heard such words directly spoken to him. He probably just did not care. He tried to accept his and his son’s fate.

However, that day, when his left hand gripped the neck of a PTBA employee and his right hand raised a machete, Ribut could no longer contain his emotions. His mind was in chaos: about his son, about the Rp 5 million.

But Ribut controlled his anger. He released the man and left him. Then he returned to look for him the next day. This time, Ribut brought Rp 20 million in cash.

“When my child died, PTBA gave me only Rp 5 million. Here’s Rp 20 million. You lie down on that road and let the coal truck crush your head,” Ribut said to the man.

“Go, lie down! Die!”

Hafidz Trijatnika Januar contributed to this article.

Editors: Evi Mariani, Sam Schramski

Translator: WND

This article is part of the #EnergiKotor (#DirtyEnergy) reporting series supported by Earth Journalism Network through its special collaborative journalism project “Available But Not Needed,” which brings together six media outlets and more than a dozen reporters across seven countries to explore how public and private investments continue to fund fossil fuel economies in Southeast Asia.