Periods are a natural process for people with a uterus. However, conversations about sexual and reproductive health, including menstruation, remain taboo in Papua, one of Indonesia’s most disadvantaged regions. Armed conflicts, poverty caused by dispossession and deforestation, and a male-dominated society add to the challenges surrounding menstruation in Papua. A group of women in Papua and Java, with the support of a church group and human rights organization, have been working to break the taboo.

Author’s note: This piece is in memory of Mauri Wandikbo, one of the sources in the story, who passed away in June 2023.

The First Period

Melani’s footsteps broke the silence of the Sorabuts’ family home in Wamena, West Papua. That afternoon, only her mother was home, waiting for her children to come back from school.

Melani rushed to the bathroom, ignoring her mother. Inside, her eyes fixed upon her stained underwear.

“I am dying,” she thought.

She opened the bathroom door and called to her mother to come over to her. Her mother’s reaction was the total opposite of Melani’s. She was elated.

Melani’s mother went to her room and took an object wrapped in a thin white plastic.

“Mama closed the door and taught me how to attach it to my underwear. Mama also told me to wash it properly after use, before throwing it away,” said Melani.

Conversations about sexual and reproductive health, including periods, remain taboo in many parts of Indonesia, including Papua. First time menstruators often panic over the bleeding and a sense of bewilderment about what is happening to their body.

Rode Wanimbo in Jayapura had her first period when she was in sixth grade. “What was happening? I was not wounded, but I was bleeding. Of course I panicked,” she said.

Her mother never discussed puberty with her. Rode said this was because her mother was following the example set by her own mother. Papuan women of that time did not have the luxury of learning much about their bodies.

“My mother was of the first generation to receive a formal education. She graduated from middle school and then got married. Women of her generation lacked access to science and information. Even nowadays, young women still struggle with access to information, including how to calculate your menstrual cycle. I myself just learned about that after joining a workshop,” added Rode.

Vei, who requested to use a pseudonym, recalled skipping school for three days out of fear after seeing herself bleed.

“I was a senior in middle school in Wamena. I was so confused and scared […] Why was this happening? What if the blood did not stop? So I decided to stay home,” Vei said.

Vei was not the only one. Mauri Wandikbo, who is 16 years older than Vei, said she did the same thing. She said her period was a painful experience.

“For three days, I lay in my bed. I did not tell anyone but Mama, and the women in my family came and brought me food. They probably knew, but they did not ask,” said Mauri.

When she was interviewed last year, Mauri was organizing menstrual health and reusable pad sewing workshops for a group called the Women of the Indonesia Gospel Church (GIDI) in Wamena. She was one of the initiators of the program.

Mute on Menstruation

The reactions of Mauri’s family that day were a reflection of the general attitude toward menstruation in the community.

Rode experienced similar treatment in her community, where people on their period were told to seclude themselves in honai (traditional houses of Hubula tribe) for the length of their menstruation.

“I see two sides [to the practice]. Women have the time to make peace with themselves, to rest inside the honai for five to seven days. On the other hand, they may also need social interaction but cannot have any because they are considered dirty. They are shunned from society because they are experiencing filthy days,” said Rode.

Rode is one of the organizers of Women Support Women to Use Reusable Pads in Papua. She is also a chair of the Women of GIDI.

Menstrual fluid actually consists in large part of the tissue of the endometrium, the lining of the uterus, which swells in preparation for fertilization and is discharged if no pregnancy occurs. Nonetheless, a number of male-dominated societies construe menstruation as a filthy or ritually unclean phenomenon.

These include some indigenous communities living near Rode that forbid menstruating people to get near the river that runs through the area, even though it is the only source of clean water and is crucial for personal hygiene.

But not all indigenous communities share the same view. During one workshop in Nabire, one of the biggest municipalities in West Papua, one participant shared that the Mee people believed menarche could show signs of someone’s future. The menstruator’s dreams in the first days of the period were interpreted by a female elder. If the menstruator had a nightmare, the family would take measures to prevent anything like it from occurring in the material world.

Pastor Matheus Adadikam, one of only two male participants in the workshop, noted that menstruation often held women and girls back from participating in community traditions.

“There is a male-only traditional house. Women, especially those who are menstruating, are barred from entering because of traditional views. For instance, there is a view that a menstruating woman could cause a hunting party to experience failure. There are also villages that forbid women who are menstruating to take part in communal activities,” said Matheus.

***

That Sunday, teenager Jeremina Kio went to church. But when she got there, her mother told her to go home. The back of her white trousers was stained with blood.

Her mother whispered, “Eh, go home, go home! Look for your niece!”

Jeremina was stupefied, but heeded her mother’s advice and went to see Ame, her niece. They were roughly the same age, but Ame had had her period before and was ready to help.

While attaching a pad purchased at a nearby roadside stall to Jeremina’s underwear, Ame told her that as a woman, she would experience this every month for many years to come.

Many Papuan women are reluctant to talk about their periods and hormonal cycles. When they must, they speak in whispers and euphemisms. They may say they are “having an issue” or simply call their period “it”. Papuan women would more readily utter the word “otsus”, regional special autonomy, than “menstruasi”, even though the former is not part of their body.

Jeremina said that at first, it was strange for her to share such intimate stories about menstruation in a public forum, in front of total strangers no less.

“But when other women spoke, I learned to be more open too,” said Jeremina, recalling her experience years before in a workshop on menstruation and reusable pad sewing in Jayapura.

‘Women Support Women’

A middle-aged woman strained to raise her hand. She was sitting in the back of the room with a younger woman. It was hard for her to stand up because of her swollen legs, a condition caused by her diabetes. She began to speak loudly once she was handed a microphone.

“When I was a midwife in the 1980s, menstruation was taboo. It’s only now that we have begun to talk about it. Ladies, menstruation should not be a taboo. It is ours,” she said.

The Menstrual Health and Reusable Pad Sewing workshop is part of the Women Support Women to Use Reusable Pads in Papua initiative, a collaboration involving Biyung, Kewita, Women of GIDI, Bentara Papua, and Elsham Papua since 2020.

They have organized workshops in Sorong, South Sorong, the Arfak Mountains, Jayapura, Nabire and Wamena, and the events involved a total of 455 participants.

The movement began among friend groups and spread organically, with the help of some public funding. The “Women Support Women” slogan does not only ring true for the participants but also encompasses the general public. The movement aims to address period poverty in Papua – the lack of access to proper menstrual knowledge and resources – through reproductive and sexual rights education, the provision of menstrual hygiene products and improved sanitation. Through the initiative, women can support other women by giving them the fabric to make reusable pads or by donating a package of ready-made reusable pads.

Biyung’s work in Papua was initiated by two friends, Westiani and Rosa Moiwend. They initially began promoting their work to friends and colleagues, offering packages of reusable cloth pads as well as embroidered shirts made by Westiani.

“At that time, Ani [Westiani] saw my father’s painting of plants. The picture looked like a uterus. Then, Ani made embroidery,” said Rosa.

Two years later their reusable cloth pad workshop received a warm welcome among women in Papua. Biyung then collaborated with Women of GIDI, who later joined Women Support Women to Use Reusable Pads in Papua.

Other workshops followed, as well as plans to create a production center in the town of Oksibil . The news spread, and the initiative gained recognition in networks outside Papua. Nona Woman, a Jakarta-based organization that focuses on providing access to menstrual education and marketing menstrual health-related products, took part in funding the operation.

Through its Giving Months program during the Christmas and New Year holidays, Nona Woman donated 3,000 reusable cloth pads for the workshops. Another organization called Nabung Donasi also provided support with a donation of Rp 14 million (approximately US$895). Dokter Tanpa Stigma, an initiative focused on delivering stigma-free health care, held an online fundraiser among the alumni of Airlangga University and gathered Rp 1,320,000 within hours. The movement also promoted the program on crowdfunding platform Kitabisa.com.

The donations enabled the distribution of cloth pads for internally displaced women from Nduga, who were forced to leave their homes as a result of armed conflict between Papuan separatist groups and the Indonesian Military. The cloth pads were produced by the Women of GIDI in Oksibil.

The Nduga women suffered from the prolonged armed conflict. They lost access to food sources, saw their material and psychological well-being plummet and found it increasingly difficult to manage their menstruation comfortably and safely.

Rode said a number of displaced women and girls were dispersed throughout Papua, from the Oksibil Mountains, Puncak Jaya, Wamena and Intan Jaya to the border with Papua New Guinea.

Accessing these locations remains a challenge, both geographically and financially. So far, the distribution of cloth pads is limited to three areas: the Oksibil Mountains, Puncak Jaya and Intan Jaya.

The production and distribution are organized by the Women of GIDI, but Rode refused to take all the credit. For her, providing humanitarian aid had little to do with religion.

“It’s because we are all facing arduous situations that we have to give back, women must support women!” she said.

After the Indonesian government declared the pandemic over, Biyung and the Women of GIDI organized another trip in 2022. The workshops, which were initially to be held in Sentani and Wamena, were in demand among other organizations and communities.

Elsham Papua, a research and advocacy center for human rights, first heard of the workshop through Parapara Buku, a community library and bookstore. More than 10 women showed interest in participating. However, their enthusiasm far exceeded the available materials and tools, not to mention the funds. More partners were needed.

Biyung and Parapara Buku contacted an acquaintance who worked in Elsham, Ani Sipa. Elsham immediately agreed to participate in the movement.

“This is the first time Elsham has taken part in menstrual-health-related activities. But I think providing a space for women to learn about sexuality and reproductive rights is not out of the ordinary. This is something that women should’ve had in the first place,” Pastor Matheus said.

Talking and Listening

The idea of using cloth pads as a starting point for conversations on menstruation had its roots in a complaint from women in Padukuhan Kelor Kidul, Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta, thousands of kilometers from Papua. They considered the packages of reusable pads sold by Biyung too expensive.

In 2018, a package of reusable pads could be purchased for Rp 100,000, an amount not many women could spare considering the low prevailing wages in the area.

The women asked Biyung to teach them how to make their own reusable pads instead. This prompted Biyung to reevaluate its operations.

Westiani Agustin, director of Biyung, supported reusable cloth pads as a way to minimize plastic waste. However, if the solution were not available to everyone, would it still be meaningful?

Women Speaking for Themselves

Women in Papua experience multiple forms of oppression, first from men, second from military operations led by Jakarta, third from the systematic dispossession of land for infrastructure and extractive industry, and fourth from deforestation and environmental destruction.

Therefore, Westiani, who came from Java, approached the subject of menstruation carefully. She knew few of the women had the opportunity to speak for themselves and about themselves. She asked them to introduce themselves: their name, their favorite song, and the first time they menstruated.

A lot of participants said it was the first time they had heard the word “menstruation” said aloud in public.

“In village meetings or public hearings, their involvement is limited. They are invited to be there, but they come only to sit down and listen,” said Westiani.

Public meetings allow women a reprieve from their domestic work and a chance to meet with friends. Invitations for women, even if only as passive participants, still bring them pleasure.

However, the customs of the meetings discourage these women from speaking up for themselves in public.

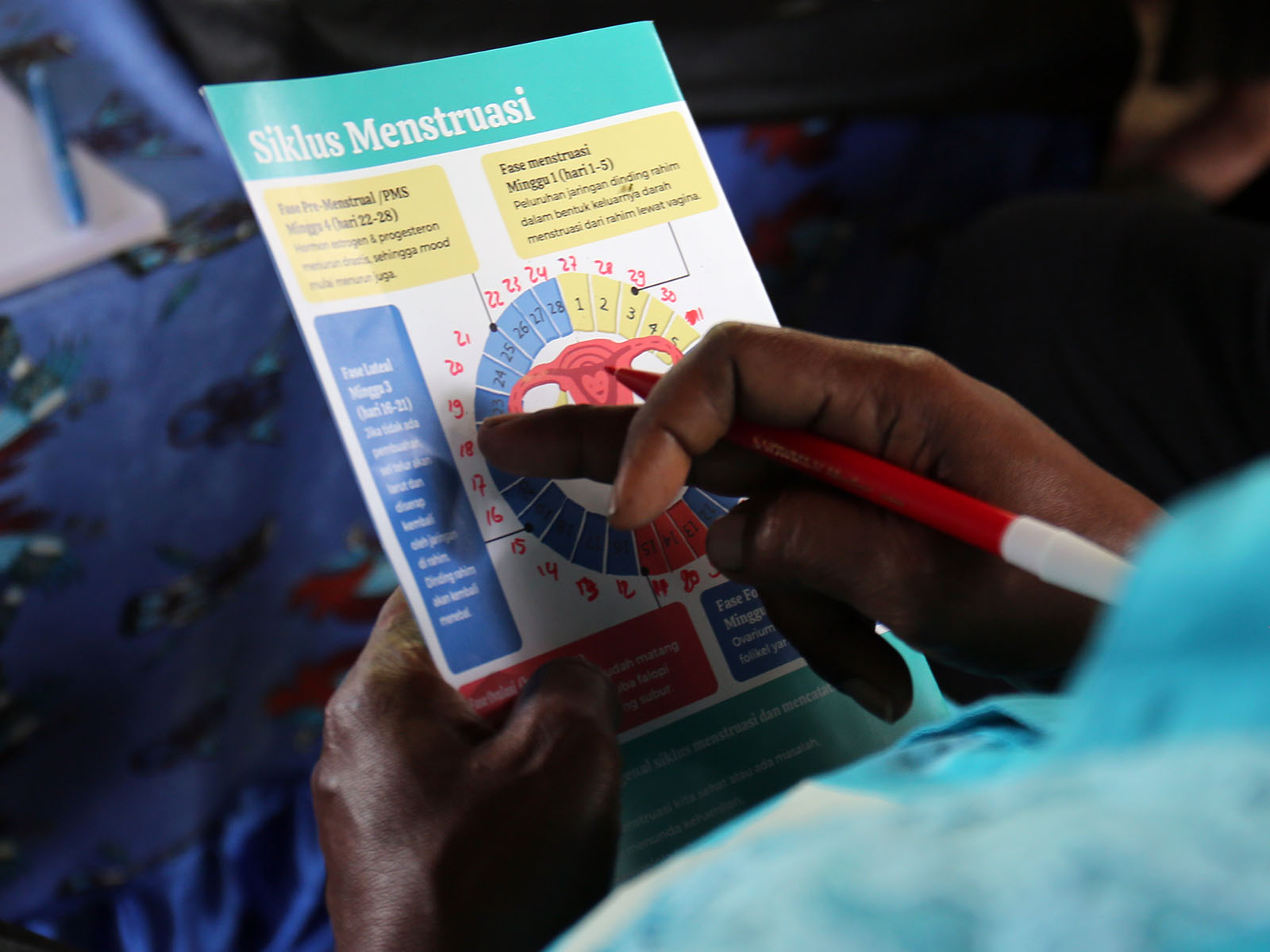

Participatory learning, therefore, was a highlight of the workshop for many participants. Inside the workshop area, participants received a package of materials to make reusable pads, along with markers and a two-page booklet on how to make and care for the cloth pads. The booklet contained illustrations on the menstrual cycle, for use in determining and keeping track of the participants’ own cycles later in the program.

Their eyes glinted when they opened the pouch containing all the materials. Westiani explained each of the tools, with some comments from participants. In each packet there were needles and thread, a seam ripper, a needle threader, four pieces of colorful patterned fabric, and a small reusable cloth panty liner to serve as a model.

“Whoa, the colors are so pretty! I want it,” said one participant.

“People might ask, ‘Eh, Mama, what’s that on your drying rack?’ This would not be considered a filthy cloth,” said another.

The workshop began with a tutorial on how to determine and keep track of the phases of one’s menstrual cycle, which Biyung emphasized as a key part of life. Rode concluded that for most of the participants, it was the first time they learned about their own monthly cycle.

The menstrual cycle is typically considered to start on the first day of the period and end the day before the next period. The average cycle lasts for 28 days but can vary. The cycle consists of different phases that can influence someone’s behavior due to hormonal changes.

“Have you ever seen our girls at home suddenly doll themselves up, trying to braid their hair in different styles? And then we, as mamas, commented that they were feeling flirty? Well, it might be because they were ovulating, so they feel a desire to be as attractive as possible,” said Westiani.

This explanation brought smiles to the faces of some mothers participating in the program. They nodded in agreement.

Rode said learning about menstruation taught her that women had two ‘brains’. A study on rats showed that the uterus played a role in brain functions such as learning and retaining memories.

“Every moment we experience is also recorded in our uterus. We, women, are unique. [When we are pregnant] we must be mindful of what we think, feel and how we behave to others because the fetus will keep it in its memories,” she added.

Cloth Pads: An Age-Old Menstrual Solution

Cloth pads are not new, and women across the world have developed their own versions to suit their climate and cultural context.

The workshop participants reacted differently to the cloth pads, but none considered it a technological breakthrough. They mostly called it a duk, or dirty cloth. According to Rosa, who learned the word from her mother, missionaries had encouraged the use of duk as menstrual pads. The materials to make duk were easily accessible by women, even those who lived in rural areas.

Febe Mabel, a health worker who serves villages in the Jayawijaya Mountains, said women nowadays were more familiar with disposable pads, even ones who lived far from markets or modern stores that sold mass-produced goods. The scarcity of such pads in rural areas, however, forced many women to ration them, making one pad last for a whole day.

Febe was concerned about this. If disposable pads are not changed regularly, they can increase the chances of infection, which can lead to infertility.

The problem, which is not restricted to rural areas, is rooted in the dearth of information on the use of disposable pads.

“Why does the manufacturer neglect to inform the consumers that their products might contain harmful substances?” asked one mother who participated in a workshop in Sentani in September 2022.

She was responding to the Biyung team’s explanation of the composition of disposable pads, which it said contained bleaching substances and recycled paper to cut down production costs.

After hearing about this, Jeremina committed to switch to cloth pads. She said her friends and family regularly suffered from infections in their reproductive organs, which she attributed to the excessive use of disposable pads. Jeremina felt using cloth pads helped her be more considerate of her body and the environment.

The pads also help her save money, as she says she is no longer influenced by advertisements that promote countless varieties of disposable pads, including daytime, nighttime, betel-scented, winged and wingless types. She used to purchase two kinds of disposable pads each month.

“I had to buy two separate products for day and night. They were expensive but still led to rashes and itchiness,” said Jeremina.

Febe, on the other hand, said she had been using cloth pads almost exclusively since her first period. Her godmother had introduced her to handmade pads made out of gauze. Febe once tried using disposable pads, but they were uncomfortable for her.

She echoed Jeremina’s complaint.

“I didn’t know for sure what the materials were, but they made me uncomfortable and itchy. Cloth pads help me save money,” she said.

Compared to other menstrual management products, cloth pads feel like old news. But many women consider them the best option for their own use. Jeremina and Febe, for instance, use cloth pads because they find them more comfortable. Some also opt for reusable pads for environmental reasons.

However, cloth pads require a lot of clean water to wash. Participants from Wamena and Oksibil noted the difficulty of getting clean water from the nearby wells.

In Oksibil, the villagers use rainwater storage tanks for washing and showering. In Wamena, Febe cleans out the tub in her bathroom regularly to prevent bacteria from growing.

The scarcity of clean water also influences the distribution of reusable pads for displaced persons in Papua. The Women of GIDI must choose areas with enough clean water to allow the recipients to use cloth pads properly.

Access to clean water is a basic right, not only for women. Through the menstrual health campaign, Biyung is also pushing for improved sanitation.

“We also advocate for sanitation. The government is obligated to provide sanitation so that women can get clean water for reusable cloth pads, especially in Papua. The government often claims that it has infrastructure development programs in Papua, but where are the results? This is related to the rights to sexual and reproductive health too,” said Westiani.

Learning about Body and Agency through Family

“I have two daughters. They are still too young [to menstruate], but now I am more ready to talk to them about their future,” said Romauli Situmorang from Oksibil.

Romauli was one of the first people to produce the program’s reusable cloth pads in Papua. After participating in the workshop in 2020, she began actively sharing her knowledge in her hometown, engaging with women’s groups in her neighborhood, at her church and through the Office of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection (DP3A).

People who understand their bodies are better equipped to face a number of situations.

Meri, from Wamena, learned about the menstrual cycle from observing her aunt as she soaked her underwear to erase a blood stain.

“I asked her once, ‘what is that?’ Then, Mama’s little sister said, ‘this is a female experience. You’ll get it one day.’ So when I eventually got my period, I was not surprised. I knew it was called menstruation,” Meri said.

Intergenerational knowledge on menstruation varies, depending on the family. I myself have used reusable pads to manage my menstruation since my first period. I learned this from my mother, who learned it from hers.

My mother showed me handmade pads made of white cotton fabric rolled around a small towel. Another piece of fabric connects the ends, which makes the whole thing look like a thong. My grandmother showed me pads made out of old batik cloth, full of patterns.

Rosa’s mother taught her and her sister to always bring a small towel to school as a period emergency kit.

Each family has its own way of providing a safe space for learning and venting. Pastor Matheus shared his personal story growing up in a family dominated by women.

“I learned to support my sisters. I know how to bake or play with things associated with girls. [My] awareness of gender equality has been nurtured since childhood,” he said.

Some indigenous groups in Papua have group initiation ceremonies for both men and women. Initiation begins when a child enters puberty. Same-sex members of the family accompany them during the rite, which can last for days and takes place in a special house.

The Mee people call such a house for women a kewita. According to Rosa, kewita are a personal space for women – from the oldest to the youngest – to learn about their life experiences. They learn how to make noken (traditional woven bags); aspects of farming, cooking, and community politics; and knowledge of the body.

The principles and values of the kewita – a place to learn, teach, and support one another – inspired Rosa to do the same within her own organization, which is named after the house.

How Men Can Take Part in Conversations on Periods

In April 2022, a quarrel broke the silence in Sira village in South Sorong. A group of 30 women rejected the participation of men in a workshop on menstrual health and reusable pads.

“Eh, No! Men are not allowed here!” said one mother, followed by similar statements by others.

Earlier, some men had come to the venue to greet the Biyung and Bentara Papua team and help them prepare the room for the workshop. After the preparation, they had stayed in the corner of the room. Westiani of Biyung then asked the female participants whether they were in favor of men attending the workshop. They were not.

The team from Bentara Papua explained to Westiani that safe spaces for women in Sira village were almost nonexistent. When the women had heard about the opportunity to talk about sexual and reproductive health, they were elated.

“Hitherto, traditions and events in the village only invited men. This is one of their efforts to get outside that box,” said Westiani.

This story reminds me of my own experience in a training organized at a GIDI church in Wamena. While waiting for others, Biyung and the Women of GIDI team chatted with participants and a pastor, Niko Mabel.

His presence caused the participants to hesitate to discuss women’s health openly. The Biyung and Women of GIDI team wanted the occasion to be a bridge for the workshop, so they led the conversation toward sexual and reproductive health in Wamena. Pastor Niko realized the awkwardness in the room and decided to leave.

Issues of sexual and reproductive health are often gender-specific, even though they influence all genders. In areas where women lack safe spaces to talk, training or workshops are a rare opportunity that must be seized by women.

When it is impossible to create safe space on their own, women need someone who can speak up for them – for instance, an authority.

Romauli shared her experience campaigning for menstrual health, supported by her husband, who is a pastor. In a speech before a workshop, he emphasized that everyone should keep an open mind when it came to the body.

The Women Support Women to Use Reusable Pads in Papua collaboration started with friendship between two women and then grew with others. However, the journey to keep the movement alive created new networks, bypassing religious denominations and sectors in social movements.

“Papuan women must be healthy! But my arm is short. I am hoping more people will lend a helping hand and do the work. If the government is responsive, then this issue can be solved more quickly,” said Romauli.

Editors: Ronna Nirmala & Evi Mariani

Translator: Devina Heriyanto

This article is part of the #PendidikanSeksual (#SexualEducation) series and has been published under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.