The persistent problem of lack of protection for Indonesian domestic workers in Malaysia has led to a policy to turn undocumented workers to documented ones through a “calibration program”. Latest updates showed the popularity of this policy, attracting 410.000 workers.

Mariana, who requested anonymity, was riddled with anxiety amidst the chaos of the Kuala Lumpur airport immigration queues. Flanked by two other undocumented workers, she held onto her fake passport, forged in a desperate measure to leave Malaysia.

The price she paid, RM2,000, weighed heavily on her mind, and the memories of that risky—albeit successful—endeavor still haunted her today.

“My hands were shivering. It still affects me to this day,” Mariana said with a shaky voice, even after almost five years of being back in her homeland in East Java, Indonesia.

This wasn’t a situation she envisaged when she first came to Penang, Malaysia back in 2009. Little did she know then that her pursuit of a better life would lead her to living as an undocumented worker, struggling to make ends meet while fearing expulsion from the country. Her undocumented status was triggered when she fled from her employer’s house, unjustly accused of theft, finding herself trapped in a life of precarious odd jobs and vulnerability.

Malaysia has long been a magnet for domestic workers from neighboring Indonesia, with Indonesians forming the most significant portion of 63,323 employed as domestic workers in the country as of January 2023.

However, a concerning trend has emerged—where an increasing number of Indonesian domestic workers are pushed into undocumented status, their lives characterized by constant fear and exploitation. As of 2017, the World Bank estimated that there are between 1.23 million and 1.46 million irregular or undocumented migrant workers in the country.

Yet the domestic labor force remains mired by issues of labor abuse. Lured by the promise of better livelihoods, domestic workers like Mariana find themselves ensnared in a web of uncertainty and vulnerability in Malaysia’s domestic labor market, owing to multifaceted reasons such as trafficking, sudden terminations and unfulfilled contractual obligations.

In response to the rising abuse cases in Malaysia, Indonesia halted sending workers last year, alleging that Kuala Lumpur violated an agreement on the proper channels to recruit workers, as it jeopardised their safety and made them vulnerable to forced labor conditions. The suspension was lifted last August.

To resolve the issue of undocumented workers, the minister of human resource has made efforts to regulate undocumented workers over the years, through calibration programs known as Rekalibrasi Tenaga Kerja (RTK) 2.0. When the government announced their latest calibration plan to legalize foreign workers, more than 410,000 undocumented migrants registered themselves by January.

Meanwhile, bilateral talks between both Indonesian and Malaysian governments continue to discuss better protective mechanisms for Indonesian migrant workers in the country. In April 2022, both countries signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to improve protection for domestic workers, following concerns of abuse.

Lived realities

Domestic worker Dewi, who requested anonymity, believed that the RTK program is a positive step towards helping domestic workers in difficult situations find a job as it recognizes domestic work alongside other forms of labor as a proper employment—for her, it is about respect.

Lina, also a pseudonym, a 53-year-old undocumented worker who has been residing in Selangor for over 16 years, also expressed her support for the RTK 2.0. She plans to return to Indonesia at the end of this year through this program, and believes in the program’s potential to provide legal recognition for herself and her friends who are undocumented.

However, she raised a concern that the program may fail to address the underlying issue of many seeking illicit routes to enter the domestic workforce. The burdensome bureaucratic hurdles and exorbitant fees they encounter push them towards these illegal means, presenting a broader challenge that remains unaddressed.

“Even with the RTK program, the main hurdle is going through an agent. The fees are so high that when employers pay it, they feel like they’ve ‘bought’ us,” she added. “The issue is about educating both employers and domestic workers about labor rights and laws about the host country.”

“Hopefully the employer can make the permit [to help document their workers] directly, rather than going through an agent,” she said.

The contents of bilateral agreements and MOUs must be followed through, Lina added, otherwise it risks becoming just a piece of paper. For instance, she argued that the MOU does not address issues that affect domestic workers who turn undocumented to escape their abusive situations, which even lead to death.

“There are too many challenges faced by domestic workers working in Malaysia. Why do we want to work in Malaysia, when there are so many examples of workers who have died in abusive situations?” Lina said. “But it’s the family’s economic circumstances. We are willing to go that far.”

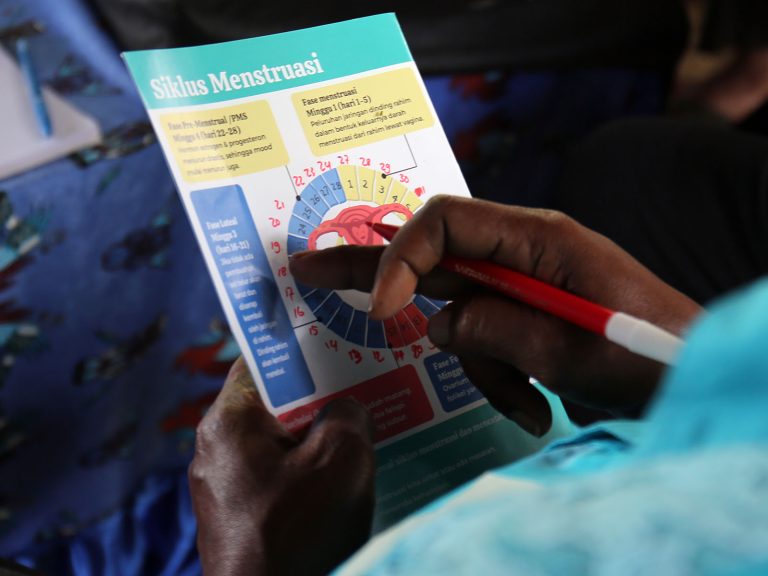

Not only are workers unprotected within Malaysia’s regulations and laws, they also confront a notable absence of protective measures from the Indonesian government. Indonesia does not have a law that safeguards its domestic workers. Despite discussions spanning two decades on the enactment of the Domestic Workers Protection Bill (RUU PPRT), the current iteration falls short, lacking crucial provisions such as prescribed minimum wage and limitations on work hours.

A recent study by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) conducted between July and September 2022 uncovered a distressing reality: that close to one third of Malaysia’s domestic workers endure forced labor conditions—where approximately 80 percent of the total domestic workers are Indonesians.

“Undocumented workers are not treated in hospitals, and often returned home. This is if you’re sick. What about when you die?” Linashe said. “It is complicated even in death.”

In some cases, domestic workers turn undocumented to escape dangerous exploitative situations like harassment and abuse.

Fighting back tears as she shared the story, undocumented domestic worker Siti, a not her real name, a 42-year-old from West Jawa recounted how she was trafficked upon leaving her abusive employer’s home. Deceived by an acquaintance who promised her a chance at better employment, she was instead held captive in a room and was almost sexually assaulted.

“I still remember entering the room she brought me to. She told me to wait. And then a man entered and locked the room,” she said as she described in harrowing details how she finally summoned the will to escape through the toilet.

Domestic worker Suraya, who requested anonymity, a 44-year-old from Sumatra, has also witnessed the fear that gripped her friends who did not hold a passport nor permit. Being documented, she would help her peers out with medication as they could not readily access healthcare services as she can.

“Their movements are restricted. They have to hide and know exactly what time the bus to work will arrive so that they don’t get caught at the bus stop.”

In one incident, she watched her friend get taken away by the police. “It was so painful to see it happen right in front of my eyes, when they took her. And you can’t do anything,” her voice cracked as she recounted this incident. “It’s not a choice to be undocumented—sometimes their employers don’t want to make the permit because it’s a hassle. Sometimes they’re duped by agencies.”

Suraya said she was fortunate to have a kind employer, whom she continues to work with for almost 18 years now—she never had her salary withheld, and had days off a month ever since she started.

“But this is really a case of being lucky. What if I am not [as fortunate]? People don’t realize how difficult it is for a domestic worker,” she said. “Being undocumented is not a choice.”

Impact on the next generation

The issue also casts an impact on the lives of children, who often bear the brunt of their parents’ undocumented status.

Malaysian-based non-profits like Permai Penang, are taking a proactive stance by organizing educational initiatives modeled after the Indonesian school syllabus to bridge the education gap for impacted youths.

“These children need education,” said Muhammad Mukhotib, an officer of Permai Penang. “Even according to international laws and human rights, children must receive education.”

Deprived of legal recognition and access to essential services, children grapple with barriers to education, healthcare and a stable upbringing.

Committed to addressing these issues, Permai Penang organizes three classes a week to accommodate children aged 6 to 13. The classes, which haves been running for 1.5 years, are also taught by Indonesian students at local universities to ensure that children receive basic and crucial skills such as reading, writing and listening.

Siyat Said, the headmaster of the Permai Penang classes, shed light on the reality that some of these children, at the age of 10, still struggle with reading—an outcome of having no access to education owing to their undocumented status.

“Who else will teach them if not us? They just want to be like other kids,” he said, highlighting the need for intervention.

“Our hope is that they can one day get registered as Indonesians, and return to pursue their studies. Who knows, they may even become diplomats,” said Mukhotib. “Who knows what their future is?”

Mukhotib said that when it comes to issues of undocumented status, it comes with monitoring and ensuring that rules are followed.

Mukhotib urged that addressing undocumented status entails stringent monitoring and adherence to the rules. The ultimate solution, he said, lies in streamlined processes, making it easier for domestic workers to apply for employment in Malaysia.

The goal is to rise above outdated practices and create a more humane and just labour system—one that eliminates the remnants of slavery and ensures the dignity of every worker.

“Slavery is no longer acceptable,” said Mukhotib. “Labor should be humane.”

Reforming Systems

Glorene A. Das, executive director of labour rights group Tenaganita, also stressed for urgent reforms and increased international collaboration to address these systemic issues and provide avenues for workers to emerge from the systemic challenges.

Based on Tenaganita’s case management in 2021-2022, Das shared that 90 percent of domestic workers they met became undocumented not to their own fault, where they are promised a contract and salary before leaving Indonesia.

“Most of our foreign domestic workers or migrant domestic workers do not know the difference between a tourist visa, a working visa, or even a student visa to begin with,” Das explained, emphasizing their vulnerability to exploitation by unscrupulous agencies. “She is completely in the hands of the agencies.”

While past government efforts offered amnesty to undocumented workers, Das aspires for a more empowering approach. She advocates for direct access to information for domestic workers, allowing them to register themselves and claim their rights.

Undocumented worker Mariana, who has returned to West Java, echoed the collective hope for a promising future, one where fellow domestic workers can navigate a system that protects their rights and ensures their well-being. Like her peers, she hopes for a more efficient system where domestic workers are better empowered and have the power to directly register themselves as laborers in the country.

“I don’t want my children to be affected by this,” she said. “But I do want them to know that being a domestic worker is just as dignified as other forms of labor.”

*Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identity for fear of reprisal

This story is supported by the Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD) Media Fellowship on Migration and Migrant Women’s Human Rights

Editor: Evi Mariani