Stories of supernatural encounters surrounding the construction of Jalur Jalan Lintas Selatan (the Gunungkidul Southern Lane, JJLS) reflect the traditional beliefs of nature being “sentient” and fighting against anthropocentric development.

I – The Tree that ‘Refuses’ to Fall

Up until this day, nobody knows what truly happened on one afternoon on the banks of Telaga Kajor in 2022.

A worker’s chainsaws unknowingly switched off every time they were in close vicinity to the old giant teak tree. The engines were not faulty, for they would instantly work again the moment they were brought far from the tree.

The peculiar occurrence spread like wildfire among the locals, recounting the tale with one simple premise: “Wit jatine ora gelem ditebang” (The teak tree refuses to be cut down).

Located among the hills of Gunungkidul, Telaga Kajor is a natural pond that served as the main water source for the people of Dusun Wuluh and Dusun Ngande-ande in Kapanewon Tepus, Gunung Kidul. ‘Dusun’ is a local term that refers to a hamlet—a smaller settlement found in rural areas, distinct from a village.

Prior to the onset of a drought in the dry season of 1986, the one-hectare pond served as a vital resource for drinking, farming, cultivating, and even swimming and fishing. Beyond its material functions, Telaga Kajor holds significant spiritual importance for the people of the two hamlets.

The area is sengkeran ground, signifying its sacred status exclusively reserved for rituals. In Javanese sengker translates to prohibited, indicating its restricted nature. sc

“This area is known to be the most sacred. It’s also known as lemah OO (Ground OO or Ground Zero), it should be left alone as it functions as papan lelembut (domain for spirits),” one of the elders in Dusun Wuluh, Saido (60) explained. .

It comes as no surprise that flanking the pond, towering trees stand still, dense and thick like giants guarding their homes. Among these trees stands the giant teak tree, impervious to the axe’s edge.

Saido explained that the 40-metre-tall tree is indeed sacred to the locals—white langse cloth is wrapped on its strong trunk, similar to the kain poleng tradition in Bali. Some Panjang Ilang (offering baskets made from dried coconut leaves) and a golden goblet were placed around it to honor the spirits.

The tree, approximately 50 years old, is considered relatively young in comparison to trees growing in the wilderness.

The locals believed that the teak tree was a home for spirits that guarded over the hamlets—Ki Loreng and Mbah Toma as the locals called them. Before inhabiting the teak, these spirits resided in a hundred-year-old caricature plant bush, locally known as Pohon Wungu which was cut in the 1980s by the head of the hamlet. These two spirits are believed to be watching over the balance of the cosmic power and maintain equilibrium in the area.

“Back then, this place was preserved and maintained for every Rasulan (post-harvest ceremony and festivities), the tree was always presented with offerings, like the Panjang Ilang on the teak tree. The tradition came from our elders, so we actively keep up with it,” Saido, whose house is only 500 meters from the pond bank, elaborated

“Back then” becomes an important phrase in Saido’s story, because the pond, trees and tradition have now been eradicated since the area was part of the construction route for the national strategic project of Jalur Jalan Lintas Selatan (JJLS).

The JJLS project stretches from Banten to Banyuwangi—a 1,600-kilometre road that initially was the strategic program of the East Java Provincial Government. It was later adapted and improved as a strategic national project.

The work commenced in 2004 with a completion date set for 2024. Spanning 88km in Gunungkidul Regency, JJLS undertook its final11 km stretch of construction through Tepus-Jerukwudel-Planjan which began in 2022. Lamentably, Telaga Kajor which was a spiritual pulse for the locals was part of the JJLS construction plan.

Before the workers could level the ground for pavement, the initial step was to cut down the sacred teak tree.

As the chainsaw would not start for unknown reasons, the JJLS workers later called Saido. Being one of the elders, Saido handled various supernatural occurrences around Dusun Wuluh. For him, the issue was clear: the tree refused to be cut down because the parties involved in JJLS did not ask for permission in kula nuwun (the proper way). He believed that the tree spirit and other specters dwelling in it were against the eradication of their home.

“Those involved in JJLS came to us and requested us to move the spirits so the construction would go along smoothly. As locals, all we could do was speak heart to heart, mind to mind, so ‘they’ would move willingly, kanthi dhasar ora meksa, we had to negotiate.”

Saido and the elders performed a ritual spanning seven consecutive Thursday nights, during which they abstained from sleep. On the last Thursday night, the elders claimed to have communicated with the spirits telepathically, according to Saido. The notion that the elders are capable of communicating with non-human entities, including spirits, is no strange concept for the locals.

The negotiation, culminated with Ki Loreng and Mbah Toma—the teak tree spirits allowing their dwelling to be cut down, but with a condition: they would only move to a new teak tree or caricature plant planted facing directly to their former home, Saido said.

The caricature plant is an evergreen perennial plant known to guard spirits. “They said that if the road served as a public facility benefiting future generations, they would not lay a finger on the construction process,” Saido continued.

***

On the scheduled day, the cutting was carried out along with the ritual to “relocate” the spirits. Many offerings were given, followed by the planting of the teak tree and caricature plant seedlings.

The old teak was finally put to the ground after being cut following the ceremony. Saido claimed that when the chainsaw finally came into contact with the trunk, a fire sparked. It was odd, “It was as if the trunk was plated with steel, the chainsaw made a buzz sound like it was cutting steel. All of the people, workers, everybody saw. Locals thought they [the spirits] were still struggling,” he recounted.

Yanto, head of Dusun Ngande-ande, believed that the spirits were refusing to leave the tree not only because of bad manners but more importantly because the cutting of the tree would mark the beginning of the end of their whole ecosystem.

Telaga Kajor underwent a transformation, excavated and filled to a depth of 12 meters, the stump of the teak tree was buried. The soil employed to fill the pond was sourced from a nearby hill, which using dynamite and an excavator drill.

“We called the hill Gunung Galingan, it was a sacred burial ground in the area. The spirits probably refused to move because they thought, what if in one or five years there would be another construction and their new home would be cut off as well,” Yanto said, pointing to what used to be the hill.

“But they [the spirits] knew that it was not the villagers’ decision, they understood that there is a government in charge.”

Now, the sacred landscape of Telaga Kajor, the giant teak, and Gunung Galingan are flat empty ground, leaving only memories and names.

The seedlings of the teak tree and caricature plant for the spirits are relocated on the edge of the JJLS road, behind a wooden fence made from the trunks of their old home. But the site no longer exudes an aura of sacredness. When we came to visit, the fence was broken and the seedlings were covered with soil, one would need to look hard to find their traces.

Stories have been circulating that JJLS employees working graveyard shifts freaked out when they saw two elderly people glowing red on what used to be Telaga Kajor. They were glaring at the workers. The locals believed the spirits continued to resist.

“They got scared and most of them refused to work late,” Yanto explained.

II – ‘Explosion-Stopping’ Rocks

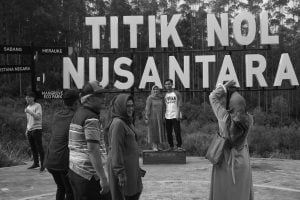

The southern part of Gunungkidul is known as Gunung Sewu, meaning a thousand mountains, aptly named after its hilly landscape. The landscape is believed to have formed hundreds of years prior by the rising sea floor.

The locals built a civilization among the valleys and winding roads following the contours of the hillside.

Every living being coexists within a shared space as a single biotic community, carrying out their roles in the age-old daily rites that have been going on as long as history. One of the most important parts of their community is Dhanyang—guardian spirits of the village.

Watu Putri is a sacred site believed to be the resting place of the Dhanyang of Balong Village or Desa Balong in Kapanewon Girisubo, Gunungkidul. The 2 x 2-meter rock is kept inside a hut with a wooden roof. The site stands by the village road on the slope of a green hill, surrounded by teak woods and shrubs.

Every year, the locals hold a kenduri/nyadran procession to honor the ancestors as a symbol of harmony between humans and other beings cohabitating in nature.

The locals believed that Dhanyang Watu Putri was a guardian spirit who had been watching over their lands and hills since immemorial time.

It is believed that the Dhanyang showed his powers when the hills were split in half to connect the route of JJLS in the name of public prosperity.

The cutting of the hill left a peculiar sight to the locals. Watu Putri was left unscathed, but only five meters in front of it, the hills were no more. The only hills left were located across it, separated by 20 meters of empty land ready to be paved.

An image of Dhanyang Balong sitting inside the hut, heart wrenched upon witnessing the hills he guarded, destroyed like mounds of sand being kicked around, came to mind.

Bambang (63), a cultural activist in Balong, recounted that JJLS planned to flatten down all of the hills at first, including Watu Putri. But several peculiar occurrences took place. “The worker tried to blast the soil beneath Watu Putri using dynamite, they tried three times but not one exploded,” he said, witnessing it firsthand.

The use of dynamite in JJLS construction has been considered to be risky due to the karst topography of the landscape—the rocks are porous and there are lots of underground cavities.

Wahyu Widyantoro, Assistant Executive of the National Road Development Working Unit of Yogyakarta, as quoted from Harian Jogja, claimed that the method using blasting dynamite is only done to crumble the stones, not to explode them entirely.

“When the dynamite was aimed a few meters to the north, it exploded. Strange but true. Maybe it was aimed too close to the rock, considering that [it is sacred] nothing should be done to it,” Bambang explained.

As a response, the people of Desa Balong made a request to the village chiefs that the sacred sites be left alone. The request was granted and thus, the project was moved several meters to the north.

***

Similar to Telaga Kajor, the locals refer to Watu Putri as a sengkeran ground.

Towiryo (87), juru kunci who cares and watches for Watu Putri, explained that the ground was set as a place for spirits and bad energies to prevent them from disturbing the lives of the villagers.

Towiryo believes that the spirits have similar lives to humans.

“Anything you want to do you have to uluk salam (ask permission), don’t act pinter lan wani (arrogant),” he added.

Many times facing similar obstacles, JJLS finally requested help from Towiryo. A certain Friday—considered sacred on the Javanese calendar— he, along with the locals conducted rituals with a complete set of offerings in Jumat Kliwon.

“Before the hills were split I requested ‘them’ to move temporarily, kana lunga golek papan sing penak dhewe-dhewe (you may go your own ways finding homes you see fit). When the road is finished, then you may come back,” he said.

“They decided to move, though a bit forced.”

Moments after Towiryo conducted the ceremony, the locals saw hundreds of snakes slithering down from the hilltop, in and out, and then disappeared among the hills and bushes.

“A neighbour, Mas Kasit, was going to catch one snake, but he got biten. It was awful,he received 57 stitches. They were massive snakes. Mas Kasit claimed that their eyes were bright red,” Bambang recounted.

Bambang suspected that sengkeran grounds might be a suitable breeding habitat for snakes. However, t due to the vibrations from the construction machines, the snakes slithered away.

On the irrational side, he added, “I don’t mean to relate everything to mystics, but the number of snakes coming out simply didn’t make sense, and they came out right after the ritual too. Probably just regular snakes, but we can say that they served as the medium of the spirits that were driven out. Like people, animals could be possessed,” Bambang said while gazing at the horizon.

“Nuwun sewu (asking for permission) matters so much, creatures like them inhabit such places because it is the most comfortable for them. They’re just like us, if our homes are to be demolished then we can do nothing by complying as long as we receive the compensation. But here, something would feel off,” Bambang said as he pointed to this heart.

III – Watu Manten, a Couple of Trees That ‘Fight’

Compared to the others, the story of a supernatural occurrence in Watu Manten might be the most popular tell-tale.

In September 2019, Yogyakarta-based local media outlet reported on a ritual aimed at relocating a sacred site in Desa Semugih, Kepanewon Rongkop, Gunungkidul. The undertaking was portrayed as described as a particularly challenging process, so difficult that the local elders gave up and a spiritual practitioner from Keraton Yogyakarta was summoned to intervene and address the crisis.

For two months prior, the JJLS workers had tried to split the car-sized rock using dynamite and an excavator drill, all to no avail. The excavator was reported to stop dead on tracks, and the drill broke down even though it only struck the soil.

Bisma, the spiritual practitioner from Keraton Yogyakarta explained that the sacred, known as Watu Manten, is a historical landmark. It marks the first opening of the forest for human settlement that is now known as Desa Semugih.

Manten means bride and groom in Javanese.

“There are two versions of the story, one mentioned that there was a bride and groom who had to sacrifice themselves for the establishment of the homestead, while others said it was because they broke the taboo and therefore were cursed,” Bisma said.

He also added that the two spirits have been dwelling there for hundreds of years. The spirit of the bride and groom are said to have incarnated as two teak trees growing above a rock.

The roots of the trees infiltrated and made knots within the rock, like two couples on their wedding altar. The locals say the trees never grow nor wither.

“The Dhanyang are not willing to move because the first negotiation was too arbitrary, as if the supernatural realm always concedes to human demands,” Bisma continued.

He believed that spirits and the supernatural are more sensitive in perceiving the intention of humans who communicate with them.

“They know whether your intention is for a good or a bad cause. So, when communicating, there should not be any business interest, profit or loss. I intended to sincerely help them to move because having them crushed down would not be good for the environment,” he stated.

***

12 September 2019, Kamis Kliwon, around noon, is the most perfect time for negotiation, Bisma said.

He brought along seven abdi dalem (courtiers) Pengulon-Kanca Kaji of the Keraton to the location, complete with various offerings to do the contact.

“They [spirits] are more humane, they always keep their promises. And so we did the negotiation, discussing what we needed and what they wanted, and then they demonstrated their approval,” he explained.

One of the offerings was a pair of chickens, one hen and one rooster. Many eyewitnesses claimed that when the ceremony began and the chickens were let out, they mingled with each other right away. The chickens trotted around the rock and watched over it. The rock was cut smaller so it could be moved to the other side of the road construction.

Up until now, the teak trees on Watu Manten are still standing upright, though their aura of sacredness faded along with the thickening asphalt.

“I pretty much have handled a lot of similar encounters during the construction of JJLS, from Panggang to Girisubo. But no need to make a ruckus of it, just do what needs to be done so the balance of nature is maintained,” Bisma stated.

For Bisma no matter what stories and beliefs people held, the most important matter is the preservation of such historical and cultural assets. He regrets that the conservation of local wisdom is not considered as important in the planning of national infrastructure.

“When they encountered it first-hand (sacred sites and supernatural occurrences), they went out of their way to look for a practitioner. It’s important to keep the ecosystem, the project, and the locals,” he stressed.

IV – ‘Collective Fear’ of a Deteriorating Ecosystem

Though it seemed strange and uncanny, many stories of supernatural encounters like those mentioned above represent the common belief of the traditional people, be it in Java or any other region.

Originating in Bali, the term Sekala Niskala, embodies the concept that that our reality is built from the complex interrelation between the visible and invisible, the physical and the imagined, and what could be understood through mind and senses.

Hence, the said that supernatural events were far from strange for people like Saido. “When nature is disturbed, there will be a response from them, it’s only natural. But it’s niku mung turene, it’s only an old wives’ tale,” Saido laughed.

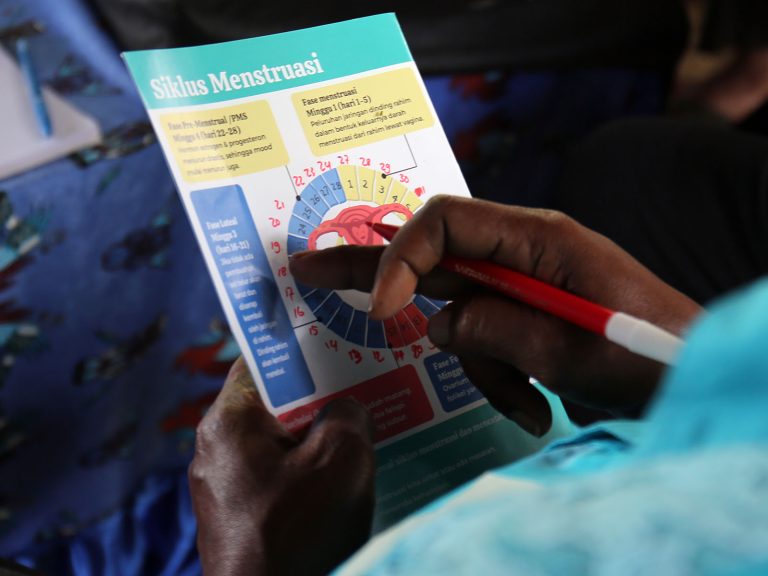

Saras Dewi, a writer and ecofeminism activist, explained that strange natural events could be seen as a form of communication between humans and nature.

“Everything we see as a superstition or supernatural thing could be our way of connecting with nature. For example, this occurrence shows that nature is sick, scared, so no wonder that there are lots of magical stories,” Saras said.

“There is a world on a different layer to our factual realm, which requires sensibility and imagination to be perceived. The locals reached that layer through rituals, ceremonies and offerings.

Amitav Ghosh, in his book, Nutmeg’s Curse: Parable for Planet in Crisis, questions Western (colonial force) assumptions about non-West people, including their beliefs that nonhuman can act, communicate, and tell stories.

“What if it was the people who were regarded by elite Westerners as brutes and savages— the people who could see signs of vitality, life, and meaning in beings of many other kinds— who were right all along? What if the idea that the Earth teems with other beings who act, communicate, tell stories, and make meaning is taken seriously?” wrote Ghosh.

“So the true question then is not whether non-humans can communicate and make meaning; rather, we must ask: When and how did a small group of humans come to believe that other beings, including the majority of their own species, were incapable of articulation and agency? How were they able to establish the idea that nonhumans are mute, and without minds, as the dominant wisdom of the time?”

Modernity first brought a new perspective that nature is a dead and passive object, and placed humans as a civilized creature separate from nature. This perspective would later be used to validate all the exploitative and destructive moves up until today.

A book titled The Secret Life of Plants (1973) by Peter Tompkins dan Christopher Bird (often called “pseudo-science” by fellow Western scientists) said that plants have a conscious, a soul, emotions, musical preferences, and even personalities.

Plants indeed do not have organs functioning as senses. But researches had shown that they could respond to their environment using all their parts. Plants felt pain, understood other creatures’ intentions, could follow the movement of space objects, and could predict earthquakes. In short, the book criticized the assumption that plants were passive.

John Charles Ryan, a doctor of philosophy, wrote an article, “Passive Flora? Reconsidering Nature’s Agency through Human Plant Studies (HPS)”, in Societies 2012, proposed a new science field that crossed interdisciplinary botanical researches with Indigenous knowledge as the basis. The proposed new field, Human Plant Studies, made an attempt to conceptualize plants as an active partner in knowledge production and cultural activities, as a social creature with valid agencies.

Saras Dewi views the supernatural occurrence in JJLS as a reflection of a “collective fear” that was triggered by environmental destruction.

“For the village community, especially when they are facing the destruction of nature, home, or their way of living, there is a collective fear. From trees, animals, and soil, each share their fear with humans. The human then feels panic, sadness, and frustration. It’s a form of empathy and collective unconsciousness. Our ancestors are used to such things,” she explained.

The construction of JJLS has led to the demolition of sacred trees, sites, and hills, disrupting the way of life and the living beings within the ecosystem.

The cutting of one sacred tree could lead to a total change of customs for the village locals, according to Bisma. “Erase the site, erase the history, then say to the public that ancestors are stupid. That’s our war right now, isn’t it?” he remarked. “Do pardon me but if I may say, JJLS could serve as a tool for such hidden cultural evil.”

He thinks that the destruction of the physical ecosystem would affect the astral plane somewhere. He likened nature to an orchestra, every plane, every creature has its tone.

“If there is one tree or hill missing, the music is incomplete, and it sounds discordant. If you cut one, you have to plant one so the orchestra remains complete and harmonious,” he said.

Around the JJLS construction site, the rituals and negotiations led by Bisma and other elders were seen as efforts to balance the spiritual energies disrupted by the destruction. Their aim was to bring about a unified and balanced spiritual essence.

But aside from the supernatural effect, the physical construction of JJLS allegedly has caused harm to the local communities.

***

The attack of the long-tailed macaque colony (macaca fascicularis) towards the locals’ crops has become an unsettling issue. Bambang, having a field in Girisubo, was one of the victims.

“When the monkey came, corn, rice, cassava, became their target, leaving nothing. They came in a colony of 50-100 monkeys, we stood no chance. Killing them would bring divine punishment, but not doing anything would just disadvantage us. Should we die from starvation for the sake of monkeys? There should be some clarity in terms of the solution,” Bambang complained.

The attack spread to Desa Paliyan, Saptosari, Purwosari, Panggang, Tanjungsari, Girisubo, Tepus, Rongkop, Ponjong, Semin, Ngawen, and Wonosari.

Muhammad Wahyudi, the head of Yogyakarta Natural Resources Conservation Center confirmed that the ape attack happened due to their habitat being destroyed following the development of tourism spots and JJLS.

“Even before I was born, the hill near Baron had always been the house for those monkeys. Just recently, after JJLS happened, they ran off to attack settlements,” Bambang added.

The Gunungkidul Regency Environmental Official also confirmed that the ape attack was related to the narrowing of the karst area, here referred to as Kawasan Bentang Alam Karst (KBAK) Gunung Sewu, for the construction of JJLS and other tourism infrastructure, as reported by Mojok.co.

Until today, the plan to narrow KBAK has been rejected by the Community’s Coalition of Karst Observer or Koalisi Masyarakat Pemerhati Karst (KMPK) Indonesia. They condemned the plan of the Gunungkidul Government to reduce the area from 75,835.45 hectares to 37,018.06 hectares, cutting 51.19% of the current area recognized as the Global Geopark Network (GGN) area by UNESCO in 2015.

The reduction of KBAK allegedly would bring a significant ecological impact considering that karst is dominated by porous limestone and is used as a rainwater catchment area, carbon emission absorbers, and crucial groundwater reserves.

Due to these unique characteristics, UNESCO categorized KBAK Gunungsewu as Conical Karst Hill which has a high scientific value. This karst category only exists in tropical locations like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Jamaica. This means that destruction in KBAK Gunungsewu is the same as the destruction of a precious biological site for the world.

Aside from the monkey attack, the reduction of KBAK will also impact the microbat (Microchiroptera), megabat (Megachiroptera), and nine other bat species which have pivotal roles in the agriculture lives of the locals.

KMPK Indonesia assesses that the Gunungkidul Government’s approach to the reduction of KBAK Gunungsewu is indicated as unconstitutional and biased towards the increasing investment trend that does not heed the protection of KBAK and the ecosystem.

Facing such issues, Bambang claimed that he can only do as little as common people, “JJLS marks the beginning of a new era in Gunungkidul.”

V – Asphalt and Images of Tourism Heaven

In their song, “Aspal, Dukun,” or Asphalt, Mages, the Yogyakarta music band Majelis Lidah Berduri depicted what seemed to be the story of JJLS and the Gunungkidul people:

Aspal sampai di kampung terujung/

Sembari memanggul/

Punggungnya/

Jaringan waralaba

Toko segala ada/

The lyrics roughly translates to:

Asphalt reaches the farthest settlement/

While riding on/

Its back/

Are franchise business/

And all-providing stores/

The construction of roads is never a single project, it is always followed with another complementary infrastructure project. Following the improvement of connectivity, the “back” of JJLS’ asphalt carries the government’s dream to turn Gunungkidul into a new tourism haven.

From the site of The Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing (Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat, KemenPUPR), minister Basuki Hadimuljono mentioned that the improvement of the Pansela (Pantai Selatan, Southern Coast) road of Java is expected to turn the area into a coastal tourism center and accelerate connectivity, this would then lessen the gap between the Southern Coast and the Northern Coast or Pantura (Pantai Utara) which is more advanced.

This goal is also supported by the Special Region of Yogyakarta Provincial Government.

The funding for JJLS is taken from the National Income and Expenditure Budget and the Regional Income and Expenditure Budget of Yogyakarta, specifically taken from ABPN and APBD Yogyakarta taken from Dana Keistimewaan or Special Fund. The physical work of road construction has become the responsibility of the central government while the land acquisition is the responsibility of the provincial government.

Throughout the construction, the provincial government has spent Rp. 1.4 trillion for land acquisition.

The improvement of people’s welfare by developing the tourism industry based on regional potential and improving the people’s capacity in tourism management is the principle mission and objective of the Gunungkidul Regent, Sunaryanta.

The tourism sector is highlighted as the star of Gunungkidul Regency Original Regional Income with a target of Rp. 28.9 billion 2023.

Meanwhile, as reported by KRjogja, since 2019 or together with the start of JJLS construction, the investment in the tourism sector of Gunungkidul has increased rapidly. The area targeted by investors is along the line of the Southern Coast, taking the shape of tourism spots, theme parks, restaurants, cafes, and even resorts.

During 2021 and 2022, the investment surpassed the target of the government, reaching Rp. 282 billion in 2021 and Rp. 634 billion in 2023. It is no wonder that new buildings began to surface along the coast which used to be managed by people.

Gunungkidul was also rumored to become the new Bali.

Responding to this, the Bali-born and grown Saras Dewi, reflected on the necessity to reassess both the goal and the dream.

“The concept of massive tourism in Bali, formula-wise, has brought pain to many parties,” she said. “As a formula, it harms a lot of people already, so why should that failed formula be applied to another region? Isn’t it like spreading the venom to parts of the body?”

Saido, who is also the head of the Pantai Siung Tourism Awareness Group or Kelompok Sadar Wisata (Pokdarwis) Pantai Siung is aware of the wave of investment into the area. Ever since opening the Siung Beach or Pantai Siung area with other locals in the 1990s, he realized that he had to empower the locals to protect them from the temptations and threats of unsustainable development.

“We do not clash with the investors, but we have different principles,” he said.

Since 1997, he has initiated two groups, the farmer’s group and the trader’s group. He encouraged people to nurture these two sources of living in balance. The agriculture fields are maintained and the harvest is marketed by the traders opening stalls and hawkers in Pantai Siung.

He formed this strategy after seeing a rapid development in tourism. Though it does bring improvement to the economy, it also causes greater potential social and ecological conflict.

Pantai Siung has long been known as the go-to beach for many climbers in Yogyakarta due to its natural cliff edges and the warmth of its locals.

“Siung is one of the areas that can’t be brought by investors. The people are still fond of farming, every harvest we hold ceremonies. Every time investors came to bargain, we answered, ‘This is not our land, this belongs to our children and grandchildren,’ we don’t want to sell it,” he explained.

VI – Solastagia and Parents’ Prophecy

History noted that the word “nostalgia” first surfaced in the 1600s following Thirty Years War. It is known as the longest and most destructive war in the history of Europe.

Johannes Hofer used the term “nostalgia” to represent a set of medical symptoms experienced by young mercenaries of Swiss having to leave their homeland for war.

The symptoms were awful, starting from fever, shortness of breath, sleep disorders, and even depression. Popular culture drove us to recognize it as sentimental feelings of longing towards a sort of comfort or familiarity in the past or to a place no longer within our reach. The nomads describe it as a feeling of longing for home—homesickness.

But could this homesick feeling be present in someone, without them having to move elsewhere?

Solastalgia.

The word is composed of two words: solace – console, and desolation, which describes the feeling of consolation, and the suffix -algia indicating pain.

The word solastalgia was first coined by Glenn Albrecht, an environmental philosopher from the University of Newcastle, Australia.

He created the word Solastalgia to describe the stress that comes from the changes in nature around our living spaces.

“This word truly defines the emotional response we have towards the changes occurring in the landscape around us throughout our life,” he explained to The Atlantic.

The first time he sensed this feeling was when he drove through his village in the southeast of Australia. He saw how the woods and mountains in a previously green village have now disappeared following the construction of coal mining sites. His broken heart is nothing strange nowadays when the destruction of nature due to natural catastrophes or human hands happens on a large scale more often.

The word Solastalgia comes to mind when writing this report.

It sums up the miserable feeling within Saido, Bambang, Towiryo, and even all the Dhanyang residing in the trees, hills, or sacred sites impacted by the construction of JJLS. Witnessing their home dug up and crushed down to be replaced with something foreign. Their living space is no longer the same.

“Well, how to put it,” Saido seemed to think, taking a sip from the cup of black coffee in front of him.

“We already know that this will happen, it has been written by suwargi simbah (the elders) since I was little. He said, ngko nek wis tekan jangkane, Gunungkidul iki bakale disabuki mori putih, negara bakal diadhepke kidul, ojo kaget – when the time comes, Gunungkidul will be covered in white shroud, the nation will be facing southward, so no surprises. The white shroud might indicate this construction, perhaps?” Saido said.

Bambang said the same, “Suk lek wis tekan jamane, watu wae enak dipangan. Dhuwit akeh, gedhene sagodhong angnka – When the time comes, stones would even taste delicious. Cash would be overflowing, the banknotes would be as big as jackfruit leaves. Turns out it happens now, anyone who owned land in the JJLS route got a compensation of millions,” he mentioned.

What was said by Saido and Bambang is called as pasemon, pasemuan in Javanese, a figure of speech incorporating a lot of symbolism, usually to present a prophecy or foreseeing and warning towards the future. They view the construction of JJLS as the manifestation of the pasemon told by the ancestors.

“But these are mere tales told by the ancestors. Elders like us could only feel glad that we can witness the green Gunungkidul, nobody knows about what others might see in the future. But kamulyane ben dipek anak putu – let the prosperity be our successors’ to have,” Bambang concluded.

On one hand, such kindness of local pasemon can be exploited, serving as unwarranted validation for irresponsible construction.

“Does JJLS adopt or apply that, we don’t know for certain. Do they ride on the prophecy to save themselves? It is possible,” Bisma said.

Now, among the rocks and earth that have been dug out along the JJLS route, the locals still go about their daily lives. They can still be seen going to the field every morning, farming, trading in their hawker stalls by the coast, and gathering in the evening.

By the beginning of May 2023, to celebrate the harvest in his village, Saido invited Komunitas Resan Gunungkidul—a conservation community whose main objective is to grow “guardian” plants through traditional rituals—to the ceremony.

After the wayang performance, the next morning they planted the seedlings while doing the memule leluhur ritual—a ceremony to honor the ancestors in Belik Welutan and Belik Gebyok, two sacred springs.

The massive trees cast shadows overthe clear water, the locals express their prayers and gratitude towards every creature cohabiting with them, seen or unseen.

“Namun pangeling-eling mawon – let this be a reminder, while all of us are still here,” he closed.

***

*Bisma is a pseudonym