Muddy water flowing in the house of Saharia, a resident of Dompo-Dompo Jaya Village in Southeast Sulawesi, on May 20, 2023. (Project M/Riza Salman)

Farmers in Wawonii, Southeast Sulawesi, are up in arms about a nickel mining operation that is slowly destroying their ecosystem.

“EVEN animals need water. Without water, we will die in vain,” Ratna griped.

The 58-year-old was upset that the water from the local spring water system that flowed into her house was now full of mud. This had become a regular occurrence ever since nickel mining company PT Gema Kreasi Perdana started its operations on Wawonii Island in Konawe Islands Regency in Southeast Sulawesi. The company, the sole owner of a concession permit on the island, is a subsidiary of natural resources conglomerate Harita Group – owned by one of Indonesia’s richest men, Lim Hariyanto Wijaya Sarwono.

Ratna could not hold back her tears. She was angry at the company that had degraded the environment and was disappointed at fellow residents who supported mining on the 706-square-kilometer island.

The mining operation has affected every aspect of her life. She has to wait for hours for the water to be clean enough to be used for bathing and doing her laundry and dishes. Furthermore, she now has to buy drinkable water, which costs her about 50 US cents a gallon.

The impacts of mining on the island’s spring water system possibly started on May 21, 2023. At that time, farmers noticed that the water spring had become increasingly murky, while the pipe used to distribute water from the island’s only water reservoir was cut off. They believed that some people might have purposely cut the water distribution to contain the problem.

Ratna had seen this coming when the nickel company started its operations there. “Those who sold the land said the mining wouldn’t harm us, but now, we’re all looking for clean water. They were fooled by the company”.

“We’re doomed here,” she said.

The mother of two has lived in Sukarela Jaya Village, Southeast Wamonii, all her life. She was never tempted to sell her land, despite being offered hundreds of millions of rupiah. The company’s money could run out in an instant, she said, but the crops could be enjoyed perennially.

“The yield of nutmeg in one year can be tons. We are criticized for refusing good fortune [by selling our land]. Doesn’t the abundance of nutmeg bring good fortune?”

Life had been sufficiently good for Ratna before the nickel miners came. Her plantation allowed her to acquire basic necessities and also save enough money to make an umrah pilgrimage to Mecca in early 2023.

“It’s totally okay to have just enough money to buy food. We must think far ahead. We have a younger generation”. She admitted that she was frustrated at the fact that her complaints had been ignored despite having to face the same problems on a daily basis.

Amid public protests, excavators proceeded to clear the land and dredge the soil. Vehicles carrying nickel ore continued to pass towards the port, which was located only 200 metres or so from Ratna’s house.

It’s only natural that Ratna plans to abstain in the upcoming elections. She feels abandoned by the council members, who are supposed to represent the people. “Our voice means nothing to the council members. When we expressed our opposition to the mining, we were thrown out like animals. We were even attacked with tear gas during our protest in Kendari. I almost died from suffocation.”

“They say investors bring prosperity, but in reality they only bring misery. The investors are killing us slowly.”

“There is no justice being served; there is no humanity. It is like living under colonialism. We are colonized by our own country.”

Fleeing into the forest

It was 6 in the morning in May 2023 in Sukarela Jaya Village, and Hastati was busy splitting no less than a thousand old coconuts to make copra. Half of the coconuts were harvested from her plantation, and the rest were purchased from her neighbours. The number of coconuts produced in one harvest time, or every three months, is usually around 3,000. Meanwhile, the price of white copra is Rp 7,500 per kg and black copra Rp 6,500 per kg. Apart from coconut meat, Hastati makes a living from selling coconut shell charcoal.

Like other residents who objected to the nickel mining, Hastati was satisfied making a living from the proceeds of her plantation. The 45-year-old was once offered Rp 1 billion to give up the 2-hectare plot of land she inherited from her parents. She was also promised a fully funded umrah and education for her six children, but Hastati never accepted the offer.

“We want to defend our lands, and the rest of Wawonii Island. It’s better for us to be independent like this,” she said. Like Ratna, she emphasised that the company’s money could run out in the blink of an eye, while a well-maintained natural environment could provide a living for many generations.

“When the mountain is completely dredged, the company will leave. What about us, then?”

On Hastati’s land grows nutmeg, cloves, and cashew nuts. Last year, she harvested 50 kg of cloves. The average nutmeg yield was 5 kg. Cashews are the most productive, as the harvest can reach up to 4 tonnes in a year.

Like Ratna, the scarcity of clean water has affected all aspects of her life. Hastati never thought she would go through this difficult time. Before the mining company came, the residents had never lacked clean water as water from the Banda Spring flowed freely into the villages.

“Now we have to go to the river to wash. How can we not be angry?”

As a form of resistance to the mining activities, Hastati refused to accept clean water from the company. It was not just about the water; it was about principles, she said. “Now we have to use river water for cooking.”

Hastati will never forget what happened in 2022, when she and other women stripped off their clothes during a protest against the nickel mining. She also hid in the forest for almost two months. She was afraid of being arrested for ‘obstructing’ the mining operation.

“We were just defending our land, but the police were chasing us as if we were thieves or murderers”.

Hastati hid in the forest with eight other residents, including Amlia who refused to sell her land for roads for the mine’s trucks and heavy machinery.

I met Amlia in her farm on May 20, 2023. She said that she hid in the forest after receiving a summons as a “witness” by the Konawe Islands Police.

“The persons summoned by the police were the ones who owned the land. As long as they did not give up the land, they would not be released. We thought it’d be better to run than answering the summons.”

Amlia and others went through difficult times when hiding in the forest. They roamed through the forest during the day and looked for a hut to take shelter when the night came. Some days they did not eat at all.

“Even when we could eat, we did not feel like eating. When we rested, we were still anxious. How could we stay calm? The police were looking for us,” said Amlia.

Like Hastati, Amlia was also promised a large sum of money. Her husband and eldest son were both offered a salary from the corporation, without the need to do any work, but she was not tempted by the offer.

Cassava, chilli, banana, and coconut trees grow near her hut. Heavy rain a few days earlier inundated part of the farm with water that carried red mud sediment. Amlia was sure the mud came from the excavated land in mining areas.

The nickel mining has further affected her daily routine as a farmer. She used to go to the farm at 8 in the morning, but now she has to start one-and-a-half hours earlier since access to the farm is blocked by the company’s haul roads. To reach her farm, Amlia needs to walk two hours from where she can park her motorbike.

During harvest season, Amlia and her husband have no choice but to carry 20 to 30 kilograms of produce by foot over the hilly roads.

“Even though it is difficult, we are still trying to do our best. As farmers, our income indeed comes from gardening,” said Amalia who was carrying 20 kg of cassava from her farm to the motorbike.

Damaged water springs

Just like the other days, Saharia, a resident of Dompo-Dompo Jaya village, woke up early in the morning to prepare her family’s breakfast. But when she turned on the tap to wash the fish, the water turned orange. Luckily, there was some water in the tank left from the rain a few days ago.

The 50-year-old is a single mother of four children. Her family owns 250 square metres of garden planted with coconuts, cashews, nutmeg, and cloves. The coconut flesh was later turned into copra, and the shell into charcoal. Saharia was consumed by anxiety as their garden could be taken over at any time by the corporation.

PT Gema Kreasi Perdana started the production and shipment of nickel ore in August 2022, shortly before the pollution of water springs began to be reported. The two main supply channels of clean water in the Sukarela Jaya and Dompo-Dompo Jaya villages have seemingly been polluted by mud since heavy rainfall hit on May 9, 2023.

On May 19, 2023, I visited the Banda Spring in Southeast Wawonii forest, about an hour walk from Dompo-Dompo Jaya Village. The spring, situated in a karst cave at an altitude of 119 metres above sea level, flows into several tributaries serving as sources of irrigation for residents’ farms and rice fields.

On May 21, the area experienced another round of rain. The water in Sukarela Jaya, Dompo-Dompo Jaya, and Roko-Roko turned dark. Those residing on the seashore were busy cleaning the gutters, removing mud carried by rainwater. Locals said changes in the colour of seawater have always occurred after rain, but never with such dramatic contrast.

When I checked the pipes in the settlement, the water was dark. Less than two hours after the rain, water distribution was cut off. Later, I met some women carrying bundles of clothes on their motorbikes. “I am going to do the laundry,” one woman shouted. “The water (flowing into our houses) is useless,” another chimed in.

I then visited the confluence of Roko-Roko River and Tambusiu-Siu River, which supply water to the Banda Spring. The colour difference between the two rivers was quite striking; Roko-Roko was slightly murky, while Tambusiu-Siu was brown. Roko-Roko is the only stream that is not polluted by the mining activities and can still be used by residents for bathing, washing, and cooking. The mining corporation has apparently distributed clean water to the residents, but some of them have refused it to signify their rejection of mining in Wawonii.

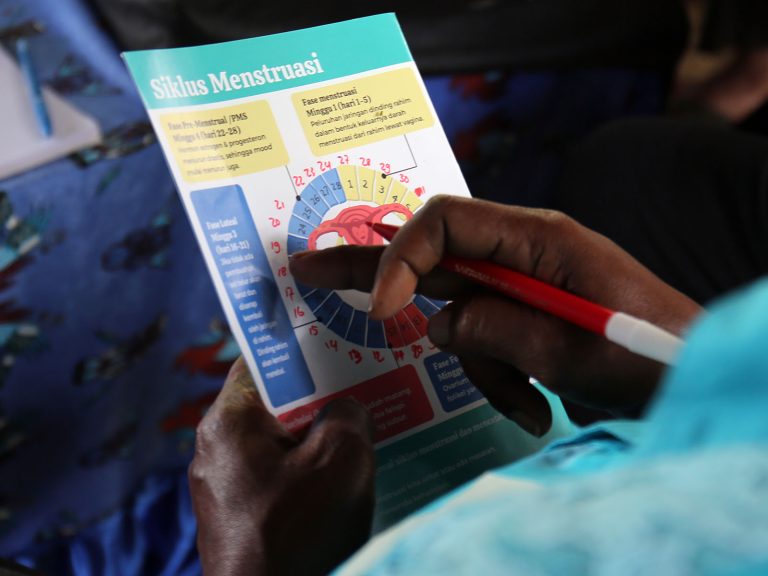

Saharia is among the local residents who object to nickel mining in the area. As a single parent, she has the dual role of taking care of the household and earning a living. The environmental destruction caused by the mining has only made things more difficult for her. To get clean water, she now has to walk to a river 500 metres away from her house. The scarcity of water has forced the family to reduce the frequency with which they go to the toilet. In Saharia’s house, there are three women who go through their menstrual phase every month.

“It is very difficult for us when we’re going through our period . We are required to clean ourselves frequently, but what can we do without water?”

Until the dry season came in mid-August, clean water had yet to be restored. The water flowing in the pipes still carried mud sediment. Saharia was struck by fear every time she used the contaminated water, but she had no other choice. For drinking and cooking, she sometimes asked for clean water from a neighbour who has a well.

“I’m worried about my family’s health. Our bodies get itchy after having a shower. We really miss the old days when the water was clean,” she said.

Nickel mining is getting under the skin of locals

Ristan has been sleep-deprived lately. The 24-year-old mother wakes up almost every night because her beloved baby also is also having difficulty sleeping. Abyan, Ristan’s nine-month-old son, has been suffering from itchy skin for the past four months. Reddish spots first appeared on his calf and ankle, and then spread to the toes and soles of his feet.

“It’s actually getting better lately. Before this, my baby’s feet were full of wounds. Very unsightly,” said Ristan while showing me Abyan’s rough skin.

Skin disease also struck Ristan, her husband, and her parents. Nahati, Ristan’s mother, had very itchy black spots all over her body a while ago. Almost all residents of Mosolo, Sinar Mosolo, and Sinaulu Jaya Villages have experienced similar ailments.

“The reddish spots felt itchy at first, and when we started to scratch they’d turn hot or even bleeding. I tried to treat it by drinking a herbal decoction,” Nahati said.

The water consumed by Ristan’s family comes from a source approximately 500 metres from a nickel mining site.

Sixty-five-year-old Nahati has resided in Mosolo since she was 5, but she only experienced the skin condition recently. The water used to turn murky after days of heavy rain. Today, however, the water changes colour after even the briefest rain shower.

Another Mosolo resident, Tika, also complained of itching. An, her one-year-old infant, was no different. The skin on his toes peeled off, and there were black scars on his legs. The mother and son ended up seeing a doctor in the city of Kendari last August.

“The doctor said there wasn’t any problem with the food we eat. He just said it might be due to the weather,” Tika said, adding that her family solely relied on spring water.

Wa Muita lives in Sinaulu Jaya Village with her five family members, three of whom are women. She has had skin ailments for the past year – ever since a nickel mine started operating nearby. She has tried a variety of medications to no avail. The water she uses for the household’s needs has been getting murky recently, and it gets darker anytime it rains.

“I have used a lot of medications, yet the itching persists. Perhaps it’s due to the polluted water we regularly consume. There’s no doubt that we are angry. It’s never been like this before”.

Jumriati, a 24-year-old resident of Sinaulu Jaya, said she was worried about her family’s health due to their regular consumption of the polluted water.

“I hope the government will pay attention to our complaints and not let the community be affected by mining’s destructive impacts. The company is profiting at the expense of our lives,” she said.

Lahadi, a caretaker of the water reservoir in Sinaulu Jaya, confirmed that the water quality had deteriorated since the nickel mining company started excavating land in 2020.

“We cannot be sure whether the pollution is due to the company’s activities. But one thing’s for sure, every time it rains for at least a day, the spring brings lumps of mud into the reservoir,” said Lahadi. “I’m not making up stories. You can ask anyone living near the mining site; the ecosystem has been disrupted.”

A local environmental official in the Konawe Islands, Hasnawati, denied claims that the water in Sinaulu Jaya had been polluted. Water consumed by the community still met the quality standards set by the Environment and Forestry Ministry, she said in a statement, adding that tests had been carried out on the Pamsimas Sukarela Jaya and Pamsimas Dompo-Dompo Jaya Springs.

“The water sample was examined in an accredited laboratory (in Kolaka Regency), and the result shows that the water meets the regulatory standards of the Environment and Forestry Ministry,” she said.

However, she did not provide the test results before this article was completed. “Those are kept by my staff,” said Hasnawati.

Muhammad Jamil, an activist with the environmental group Mining Advocacy Network (JATAM), said skin ailments were common in nickel mining areas. Similar diseases could also be found in the Pomalaa District of Kolaka Regency and Tinanggea District in South Konawe Regency.

“As far as I know, the problem has been studied by a number of universities,” he said.

Research conducted by La Maga, Ahyar Ismail, and Faroby Falatehan from IPB University in Bogor (2017) found that Tinanggea residents experienced skin disease after using water contaminated by material from nickel mining sites. In addition to the skin conditions, residents also suffered from respiratory problems, as they were exposed to dust raised up by the mining. Such air pollution affected those within a three-kilometre radius of nickel mining sites, the study found.

Defending the land

“I was devastated watching the clove trees being ripped down. It was like seeing your own children murdered,” said Wa Muita, a 43-year-old resident of Sinaulu Jaya, as she recalled the events of August 10, 2023.

A day before, residents received reports that their plantations on Mosolo hill, two hours away from their settlement, had been cleared by PT Gema Kreasi Perdana. Amiri, Wa Muita’s husband, rushed to check his plantation in the middle of the night and found that 40 of his clove trees had been toppled. Apart from that, the corporation also tore down dozens of pepper trees and cashew trees that were about to bear fruit.

Wa Muita and some 20 other farmers came by the next day. They were saddened to see the 18-year-old clove trees that had long been the source of their livelihood destroyed just like that.

“I was speechless, tears streaming down my face,” said Wa Muita.

Shortly after, hundreds of residents gathered at the plantation area. They confronted the company for trespassing, but the company claimed that it had acquired the land through other parties. Wa Muita and Amiri stressed that they had never sold their land, let alone received money from the supposed transaction. The situation quickly spiralled out of hand as members of both conflicting parties threatened each other – some with sharp weapons.

“Every time I go to the farm, I always talk to the clove trees. ‘Please bear fruit soon. We care for you like our own children. And you are the ones paying for your siblings’ school fees’,” she said.

Wa Muita has two children who are attending college; another one is in high school, and the youngest of all is in elementary school. Their tuition fees have been covered by the sale of cloves. In 2019, the family harvested a ton of cloves. The price of one kilogram of cloves in Southeast Wawonii is roughly Rp 130,000. The 40 clove trees uprooted by PT Gema Kreasi Perdana were immensely precious to Wa Muita.

Despite everything the company had put her through, Wa Muita only asked PT Gema Kreasi Perdana to stop clearing the land.

“We accept what they’ve done to us and hope the company still has some conscience. We have further requested the person who sold the land without our authorization to refund the company’s money”.

“Without this land we don’t know what to do. This is our sole source of income,” she emphasised.

Despite encountering such fierce rejection, the company has continued to clear residents’ land, said Wa Muita, forcing her and other farmers to maintain guard of their respective fields for months.

“We didn’t even have time to take care of ourselves from February to May. We did not shower, and only ate whatever was available”.

Before the trespassing incident, Wa Muita visited her field twice a week. Now she’s forced to go there more often to guard her land.

“I don’t know what to say. I feel devastated. Why are there such evil people? We desperately care for the land, and they come and violate it just like that.. On top of that, they have also threatened to evict us”.

“I hope the media, or anybody really, can help us to stop the destruction of our mother nature”.

‘We are pitted against each other’

Not only does has mining had environmental impacts, it’s also triggered family conflicts: parents and children have come to despise each other; siblings have become enemies; and partners have split up.

For instance, Sanawiahas been estranged from her parents for over three years. The family conflict started when one of Sanawia’s brothers, with their father’s permission, sold their parents’ land in 2019.

The land sale was sealed as Sanawia protested against the mining at the Konawe Islands Council Office. It was only while on her way back home that Sanawia heard her parents’ land had been sold to the mining company.

“I could only cry. The company quickly cleared the land. Since then I haven’t been to visit my parents,” said the 45-year-old woman who has four siblings, three of whom support the mining activities. Sanawia said that, among her siblings, she used to be the closest to her parents — but not anymore.

She did not know exactly how much of her parents’ land was being sold. What she knows is that the field could usually produce 3,000 coconuts each harvest season. The mother of two wants to fix her relationship with her parents and siblings, but only under one condition. “Our relationship can be repaired as soon as the mining operation stops,” Sanawia insisted.

Aba, not his real name, said his daughter was abandoned by her husband while she was pregnant with their second child. His son-in-law had offered him money provided by the company in compensation for Aba’s land, which was used for PT Gema Kreasi Perdana’s haul roads.

Aba had previously been taken to the police station for defending his land. So he was enraged when his son-in-law made a deal with the company without his consent. He refused the money and demanded it be returned to the company.

When the couple was about to build a house, Aba’s son-in-law asked his wife to take out a loan, but she refused. That was when the son-in-law brought up Aba’s refusal to accept compensation from the mining company. The quarrel escalated into domestic violence.

“One night, my daughter came to me, crying. Her right eye was bruised. I tried to reconcile the couple, and they did get back together. But, after a few days, when my daughter was looking for mussels in the sea, her husband ran away and has not yet returned,” Aba explained.

Now, his daughter and two grandchildren live with him. “I will never accept the company’s money. I’m already old, it’s true, but I’m thinking about the future of my grandchildren,” Aba stated.

Both Sanawia and Aba reside in Roko-Roko, and in this village, social divisions caused by the mining company are no longer a secret. A number of people I met expressed reluctance to engage with anybody from the opposing ‘camp’.

A legal battle against mining activities

Wawonii Island, which covers an area of 706 square kilometres is categorised as a small island, based on Law No. 27/2007 on the Protection of Coastal Areas and Small Islands. Thus, as mandated by the law, mining activities cannot be carried out on the island.

Several civil society groups noted that at least 2,214 people living in the villages of Dompo-Dompo Jaya, Sukarela Jaya, Roko-Roko, Bahaba, and Teporoko were affected by PT Gema Kreasi Perdana’s nickel mining. For the record, PT Gema Kreasi Perdana obtained a nickel mining permit in 2007. By the end of 2019, the subsidiary of Harita Group secured a mining operation permit (IUP) on an area of 850.9 hectares, around 83 percent of which was forest area lent by the state under a forest area utilisation permit (IPPKH) scheme. It was also granted permission to build a port in the Wawonii Strait.

The development, according to a coalition of civil society groups, has harmed the aquatic ecosystem, including mangroves and coral reefs, on and around Wawonii Island. The murky water resulting from mining activities has made it difficult for fishermen to catch fish. The port also keeps fish away from the shoreline. The thick dust generated by the transportation of nickel ore has also damaged residents’ respiratory systems, the coalition emphasised.

Even though the law prohibits mining on the small island, the local government has issued a regional planning regulation (Perda No. 2/2021) that covers the Konawe Islands and carves out an exemption for mining on Wawonii.

Wawonii residents, represented by the Denny Indrayana Law Firm, have filed a judicial review of the regulation. On December 22, 2022, the Supreme Court granted their request.

Through decision No. 57 P/HUM/2022, the Supreme Court states that Wawonii Island is a “small island… which is vulnerable and very limited, therefore requires special protection. All activities that are not intended to support the ecosystem… including but not limited to mining are categorised as abnormally dangerous activities… which must be prohibited… as they will threaten the lives of all living creatures on the island”.

The Supreme Court also mentions that the special planning regulation “…ignores the wishes of the community as conveyed by a huge demonstration on March 6, 2019, against the mining activities”. The court further ordered the Konawe Islands Regent, as well as the Regional Legislative Council, to revise the regulation.

However, president director of PT Gema Kreasi Perdana Rasnius Pasaribu, through his attorney Asmansyah & Partners, submitted a judicial review to the Constitutional Court to challenge a number of articles in the law about the protection of coastal areas and small islands. The articles, number 23 paragraph 2 and 25 letter k, ban mineral mining activities in such areas.

The company’s lawyer argued that the Supreme Court interpreted the two articles as an “unconditional prohibition” on mineral activities in areas classified as small islands, despite the fact that the company “possesses a valid permit” and is therefore “threatened to cease its activities and potentially suffer constitutional and economic losses”.

The company said it had invested a total of Rp 37.5 billion and 77,300 US dollars since 2007, in addition to distributing more than Rp 70 billion in compensation for 568 hectares of land affected by mining activities.

The application was submitted on March 28, 2023, and the Constitutional Court arranged several hearings in May, August, and September. The next stage is the verdict hearing.

Civil society groups have called on the Constitutional Court to reject the judicial review in order to safeguard small islands from the grip of a destructive mining industry.

“If the judicial review is granted, mining activities will be legalised in all coastal areas and small islands in Indonesia, not only on Wawonii Island,” Wildan Siregar from environment watchdog Trend Asia warned. “Both ecological damage and social conflicts due to mining will become far more widespread” he added.

While the company filed a judicial review at the Constitutional Court, the Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Council officially removed the allocation of land for mining on Wawonii Island. The Regional Regulation Draft (Raperda) concerning the 2023-2043 Spatial Planning of Southeast Sulawesi designates Wawonii Island as an integrated fishery region.

Fajar Ishak, head of the Council’s special committee (Pansus) on the Spatial Planning bill, explained that revocation of land for mining in the Konawe Islands Regency was eliminated to comply with the Supreme Court’s decision.

“The Supreme Court’s decision was issued towards the end of 2022 (and became effective this year). Therefore, we cannot ignore it. As a consequence, we decided to declare Wawonii Island as an integrated fishery area. There will be no more mining there,” said Fajar on August 29,2023.

‘This is a false allegation’

PT Gema Kreasi Perdana spokesperson Alexander Lieman denied the accusations that the company had caused environmental damage. According to him, the company has taken preventive measures to prevent air pollution such as routinely monitoring the air quality and regularly watering the roads.

“We are taking such measures as part of our commitment to protect the environment, especially Wawonii Island,” said Lieman.

“In fact, we even provided compensation for residents whose plantations were affected by mining activities,” he went on.

Regarding the murky water, Lieman claimed the water on Wawonii Island had always been like that, even before the company commenced its operations. He noted that every time it rained, the water turned dark.

“Our mining activities do not pollute the river (…) We strongly reject these baseless accusations. You can validate this with the local administration as well as the Environmental Agency”.

Murky water flowing from a resident’s pipeline on May 21, 2023. (Project M/Yuli Z.)

Lieman said the corporation actually helped the communities to access clean water by dispatching water trucks to villages, setting up a special team to find alternative sources of clean water, digging wells, and cleaning the communities’ water tanks.

“The river is clear again, and the residents can easily access clean water for their daily needs”.

Lieman’s statement does not correspond to the facts on the ground. The water flowing in Dompo-Dompo Jaya, Sukarela Jaya, and Roko-Roko villages continues to carry mud. The water was still dark by August 18, 2023, even though there had not been heavy rain for quite some time.

About the coverage:

Yuli Z. interviewed at least 20 households who oppose the mining in five villages, namely Dompo-Dompo Jaya, Sukarela Jaya, Roko-Roko, Sinaulu Jaya, and Mosolo. She visited the locations on May 19-23 and August 13-19, 2023. While reporting, she stayed at the house of a Dompo-Dompo Jaya resident.

Those supporting the mining use the clean water provided by PT Gema Kreasi Perdana which is distributed via water trucks. Yuli has observed the water distribution processes several times. The water is taken from the Roko-Roko River.

The company has drilled two wells, one in Dompo-Dompo Jaya and another in Sukarela Jaya. One of the wells cannot supply the needs of all villagers. When the water supply is extremely limited, as happened in May 2023, some of those who oppose the mining have no choice but to use the well.

This coverage is part of a fellowship with Konde.co, supported by the Earth Journalism Network (EJN).