When you climb one of the hills in Wadas village, Purworejo regency, Central Java, it’s immediately apparent why locals call the place a paradise.

Eagles fly overhead, and all around, you see forests teeming with fruit trees, including durian, palm, and coconut. The canopy is dense, almost like a rainforest, allowing just enough sunlight to reach the ground for shrubs, vegetables, and spices such as ginger and galangal to grow on the forest floor. Vines of vanilla and kemukus (tailed pepper) grow on the tree trunks.

Over the generations, the fertile land around Wadas has allowed the villagers to grow multiple crops simultaneously, giving the farmers who make up the majority of the village’s population a steady income from harvests at different times throughout the year.

The durian harvest is one of the most anticipated ones, as Wadas’ soft, creamy, sweet durians are in high demand and fetch good prices.

Marsono, a 62-year-old Wadas farmer, said that in a good harvest, one large durian tree could generate up to Rp 10 million (US$700).

“I have 10 trees, so I can get Rp 100 million,” he said.

Marsono also grows rubber trees, which he tends to every day. The rubber is worth about Rp 7,000 per kilogram. A small green mushola (prayer room) he built near his house for his neighbors is one of the fruits of his labor.

Another farmer, Suroso, showcases a tailed pepper plant, also known as Java pepper or cubeb, which grows on a tree trunk in front of his house. The pepper is used as a spice, and its oil is also widely used as an antiseptic.

“One kilogram of wet cubeb sells for Rp 50,000, while dried cubeb is Rp 250,000,” Suroso said.

During the harvest season, Suroso can obtain 20 to 30 kg of wet cubeb. After the drying, 3 kg of wet cubeb shrinks to 1 kg. If Suroso can harvest 30 kg and sell it dry, he can earn Rp 2.5 million.

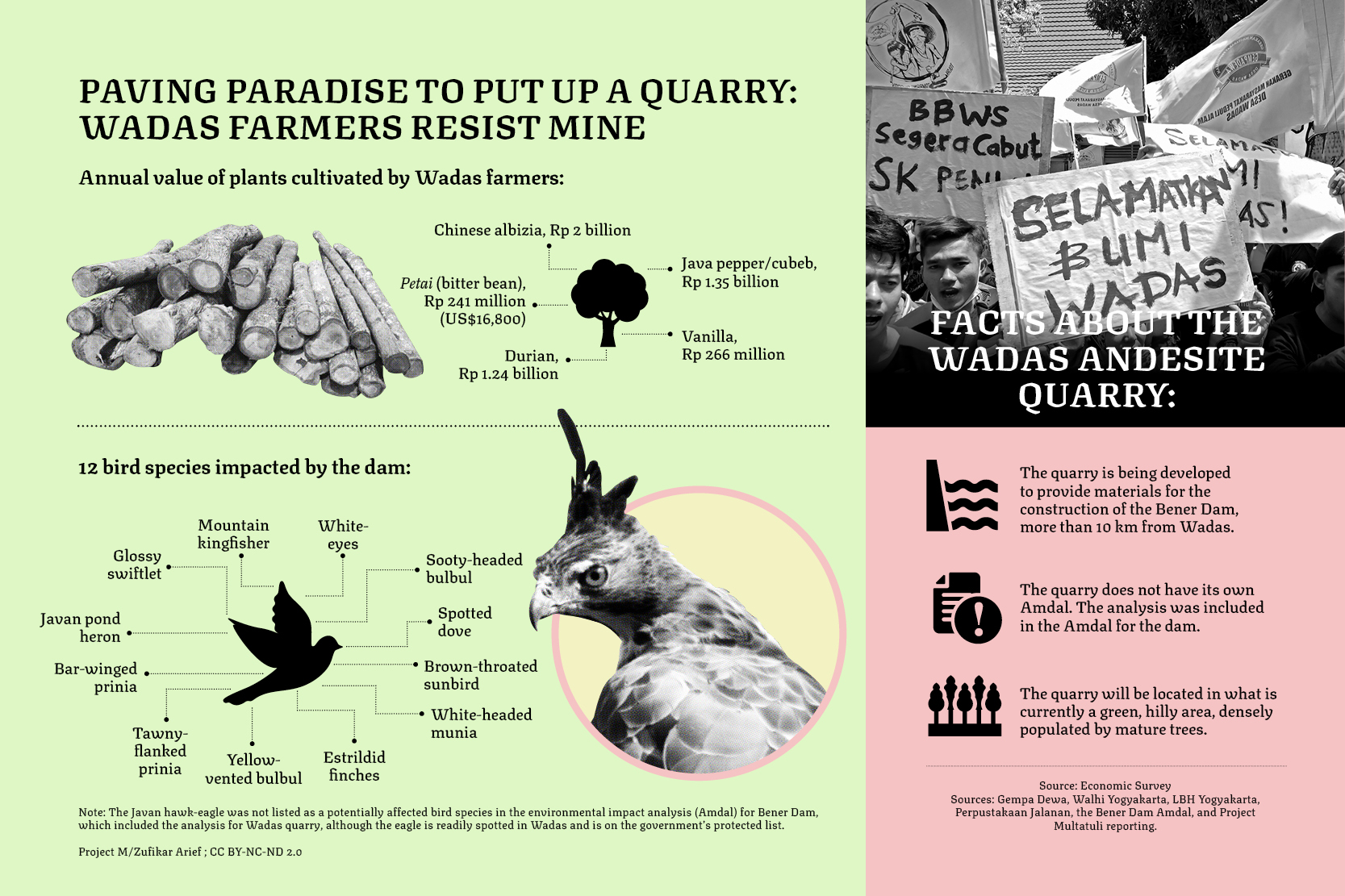

A study conducted by the Wadas Citizens Concerned for Nature Movement (Gempa Dewa) together with the Indonesian Forum for Environment (Walhi) Yogyakarta, the Yogyakarta Legal Aid Institute (LBH), and the Perpustakaan Jalanan street library community, found that all the crops cultivated on the hills of Wadas had high economic value; petai (bitter beans) are worth Rp 241 million a year, sengon (Chinese albizia) wood is worth Rp 2 billion, Java pepper Rp 1.35 billion, vanilla Rp 266 million, and durian Rp 1.24 billion.

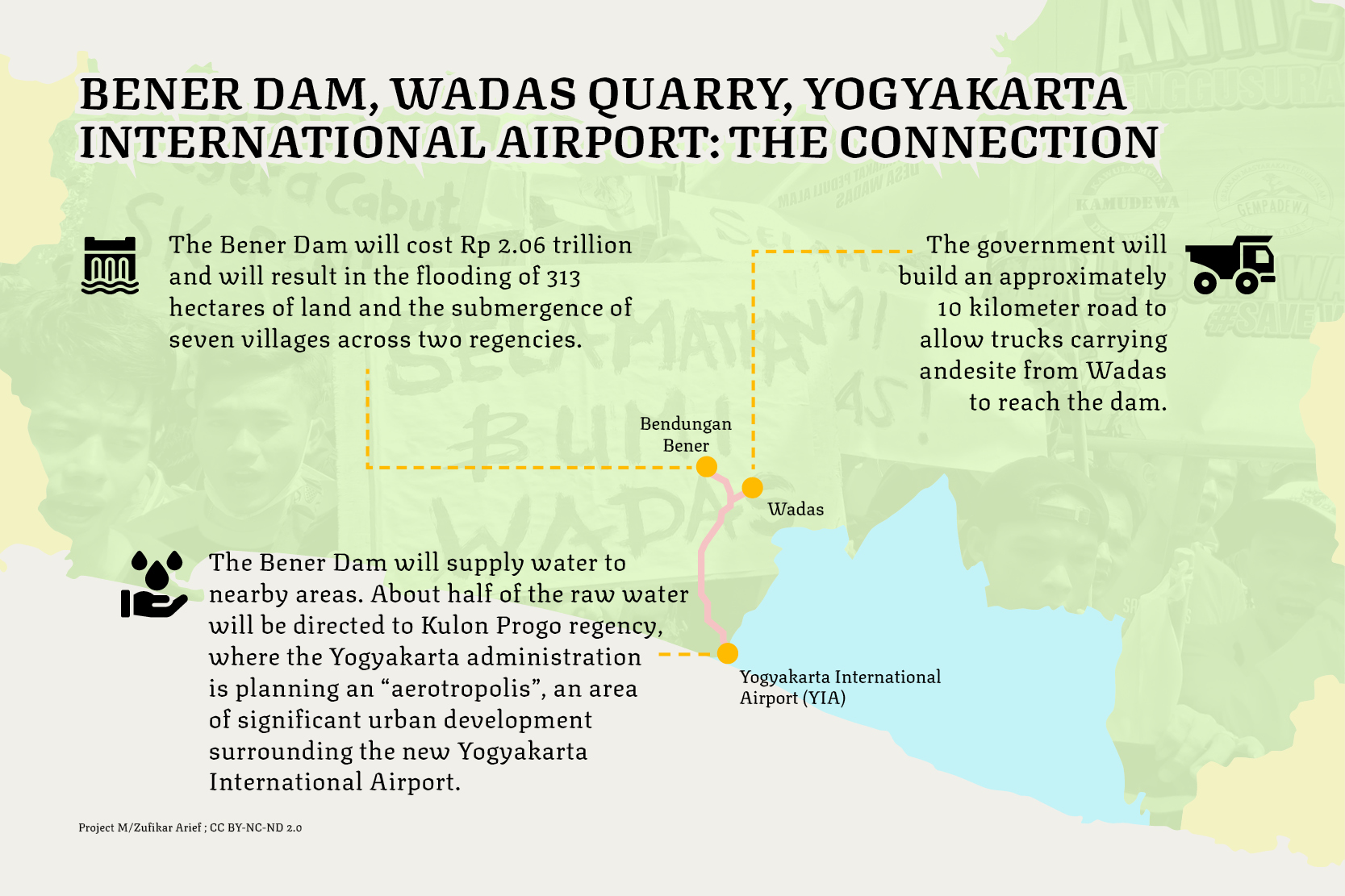

This bounty is why the people of Wadas call their land a paradise, a place that provides all they need to live – and to live well. But now, the farming community’s way of life is at risk. The government wants to level their Edenic hills to make way for a rock quarry.Click To TweetThe Serayu-Opak River Basin Management Body (BBWSSO) of the Public Works and Housing Ministry is building what is to be Indonesia’s tallest dam, the Bener Dam, in Guntur Village, 10.5 kilometers west of Wadas. President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has designated the dam a national strategic project.

The BBWSSO plans to build a 114 hectare quarry in Wadas that will supply stone for the construction of the dam. A road will also be constructed so that trucks can transport rocks from Wadas to the construction site.

The Bener Dam’s commitment-making officer (PPK) M. Yushar claimed the hills in Wadas held 40 million cubic meters of andesite but that the dam would only require 8.5 million cubic meters of stone over two to three years.

“Wadas was chosen because the rocks in its hills meet the criteria for hardness and volume. The distance is also ideal, not far from the Bener Dam,” he said.

Yushar said the Wadas people would receive compensation of Rp 120,000 per square meter of land. The land would be owned by the state but would be recovered once the dam was finished, and afterwards, the community would be able to use it again through an agreement between village-owned businesses and the BBWSSO.

Trading ‘Paradise’ for an ‘Aerotropolis’

The Bener Dam, on the Bogowonto River, will be about 160 meters high. The Rp 2.06 billion project will create a reservoir of 90.39 million cubic meters, inundating four villages in Purworejo regency and three villages in Wonosobo Regency.

Equipped with a 6 megawatt (MW) hydroelectric power plant, the dam is expected to provide irrigation for 15,519 hectares of land, reduce flood discharge by 210 liters per second, and supply water and electricity.

The clean water supply will be 1,500 liters per second. The largest share, 700 liters per second, will flow to Kulon Progo regency. Of the 700 liters streamed to Kulon Progo, 200 will go to Yogyakarta International Airport (YIA), which was built by evicting Temon farmers, some say forcibly, who had been cultivating the fertile coastal land, for the sake of boosting tourism.Click To TweetThe Yogyakarta provincial government plans to develop YIA into an “aerotropolis” spanning 7,000 hectares, calling it Java’s “city of the future”. In late December 2019, the head of the Kulon Progo Development Planning Board (Bappeda), Agus Langgeng Basuki, said that YIA’s aerotropolis would be further widened to cover a radius of 15 kilometers from the airport and would include commercial, logistical and residential centers.

The Loss of Land is the Loss of Livelihood

Wadas residents first heard about plans to construct the Bener Dam in 2013. Wadas village chief Insin Sutrisno, 75, said the majority of the villagers, comprising around 400 families, disagreed with the proposition to construct a quarry in their village. They voiced their opposition to the project when the BBWSSO promoted the idea at the village hall.

“Ninety-nine percent of us are farmers. If we lose our land, what do we do? The land is our lifeblood, now and forever,” he said.

Even though the Wadas villagers rejected the planned quarry, an environmental impact assessment (Amdal) that omitted their objections was issued in March 2018. Three months later, Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo issued a decree designating Wadas village as the site of the quarry. The permit has been extended once and will expire on June 5 of this year.

Yushar stands by the Amdal, saying that he had held a public consultation with the head of the Village Representative Body (BPD), the Wadas Village chief, the Bener subdistrict chief, and community leaders at the house of the village chief on Aug. 7, 2017.

“We also conducted a public survey. The results proved that residents approved [of the dam’s construction], but over time, some people incited others to refuse,” he said.

Yushar claimed that 70 percent of Wadas residents now agreed to the planned quarry. The BBWSSO asked the people who agreed to submit their IDs and land certificates.

“Now 313 plots of land have been secured [for construction], and only 100 plots have owners that have engaged LBH Yogyakarta because they refuse to hand over the land,” he added.

LBH Yogyakarta advocacy head Julian Duwi Prasetia, however, said the majority of Wadas residents still opposed the quarry’s construction. Since October 2018, Julian has been representing the 300 Wadas residents who have asked for the institute’s help.

‘Flawed’ environmental impact assessment

Julian said the Amdal that had led to a permit for the construction of the Bener Dam and its supplying quarry was deeply flawed “both substantively and procedurally,” invalidating the resulting permit.

Besides not including Wadas residents’ objections to the quarry, the Amdal also failed to document the eagles that inhabit the area as one of the bird species that would be affected by the quarry’s construction. The document recorded 12 bird species but omitted the eagles, a protected species. The large birds fly over Wadas every morning in search of prey.

Julian also said the public consultation held by the BBWSSO failed to comply with regulations, as it involved only village officials, excluding the residents who would be affected and environmental experts.

He added that a separate Amdal for the quarry’s construction should have been issued, instead of combining it with the assessment for the Bener Dam, as the process of obtaining a mining permit was different than that of an infrastructure permit.

“This sets a bad precedent,” Prasetia said. “In the future, if someone wants to build a toll road that requires cement, one Amdal will be enough to give permits for both toll road construction and limestone mining to produce the cement.”

Yushar disagreed. He said one Amdal was sufficient because the dam and quarry formed one unit and both processes required similar methods of excavation.

Wadas resists

Since the issuance of the Amdal, protests have escalated. The Wadas people formed the Gempa Dewa organization and Wadon Wadas (Wadas Women). These groups have been staging protests at a number of government offices, including the Central Java governor’s office in Semarang. But their pleas appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

On April 23, the Wadas farmers resisted again when a BBWSSO team arrived to drive stakes into the land. Wadon Wadas managed to prevent the team from pitching a tent in the village. The villagers then gathered and blocked the road to Wadas as they chanted prayers.

That afternoon, 400 police officers came to the village. Clashes erupted after the police fired tear gas to disperse the Wadon Wadas blockade. Nine people were injured and eleven were arrested, including Julian of LBH Yogyakarta.

During the April 23 clashes, a Wadon Wadas member named Yatimah fell to the ground when she and other women tried to take back a young boy who was being arrested by the police. The 50-year-old woman said she had the courage to fight because her rights were being threatened by the planned quarry and she wanted to defend them.

“We are fighting because we, women, are the most vulnerable to the quarry’s construction,” Yatimah said.

She said the quarry would destroy the community’s living space and sources of clean water. Her land, where she currently grows palm trees, is to be mined according to the development plan, and Yatimah will no longer be able to make the palm sugar she relies on for her livelihood.Click To Tweet“We are not against government programs. We only ask one thing; we do not want quarries in Wadas Village,” she said.

‘We are water experts, don’t worry’

The BBWSSO’s head of dam construction, Tampang, rejected claims that the quarry would disrupt the water supply and cause landslides but did not elaborate further.

“We are water experts, don’t worry,” he said.

He also called Wadas barren land, despite ample proof to the contrary. Even on Google Maps, you can see green hills spread across Wadas, full of large trees.

Tampang said the farmers could buy land in other areas and buy motorcycles or cars with the compensation money. He said this would be an improvement for them.

Yushar added that farmers whose land was taken would not lose their incomes because they could work in the quarry as well.

The government promised similar things to the farmers of Temon, Kulon Progo, during the construction of the YIA. However, a farmer named Sofyan said the reality was not nearly as rosy. “Not everyone can buy farmland again. Some can only use land that is far from where they live,” he said.

The Latest Research on Dams

The benefits of dams are now widely questioned by the international community. They are considered costly, environmentally damaging, socially challenging, unsustainable, and no longer suited to purpose as a result of climate change. Liz Kimbrough, in her article “The Hidden Costs of Hydro: We Need to Reconsider World’s Dam Plans” published on environmental website Mongabay, cited a study by Michigan State University that found that both the cost and impact of dams were often underestimated.

In Europe and the United States, the trend is to destroy dams, not build new ones. In the US alone, an average of 60 dams have been destroyed each year since 2006. This is in stark contrast to developing countries, which are currently building around 3,700 dams worldwide.

In his report “The unacceptable cost of big dams” published by The Guardian, environmental journalist Paul Brown also discussed the negative impact of large dams. He cited a statement from the World Commission on Dams that noted that 45,000 large dams built worldwide had had significant detrimental effects, harmed the poor, and failed to provide electricity and irrigation as planned.

Tampang dismissed the research. “Those are just individual cases,” he said.

He guaranteed that the construction of the Bener Dam would continue as planned, using the andesite from Wadas. For him, other locations were not an option.

Sitting on his front porch, Marsono puzzled over why the government would want to destroy his paradise, when Wadas’ hills generated so much income for its people.

“The government says it wants to reduce poverty, right? So why does it oppress farmers and take our land?” he asked.

The night before, Marsono led a prayer session for his neighbors in his musala. They prayed for God’s help to prevent the construction of the quarry.

Translator: Alya Nurbaiti

Editor: Mawa Kresna